Meniscal cysts are well-defined and documented lesions that were first reported by Nicaise in 1883 (according to Kurian, 2003)1 and are located adjacent to the peripheral margin of the meniscus. They are almost always associated with a meniscal tear.2 Even though Barrie3 reported meniscal cysts in up to 7% of patients undergoing meniscectomy, others have stated that the true prevalence is probably about 1% of patients who undergo meniscectomy4. In addition, while some authors have advocated that lateral meniscal cysts are three to ten times more common than medial cysts5, others have stated that medial cysts are more frequent6;7. Meniscal cysts are most often seen in young adults and occur more frequently in men than women.8

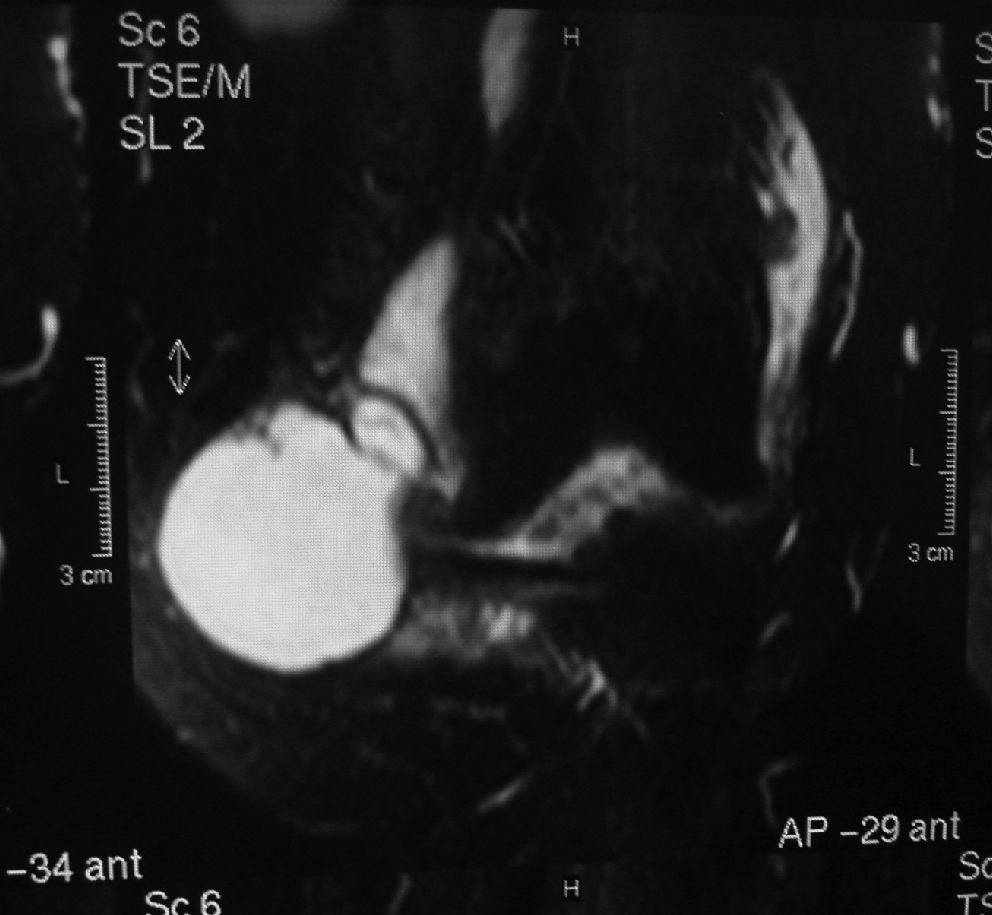

CASE REPORTA 66-year-old woman had a history of mild pain in the left knee that had increased in severity over six months. There was no history of trauma. On examination, the patient had pain in the medial aspect of the joint line, with focal tissue swelling on the medial aspect of the knee. The swelling was large (Figure 1) and painful, but the knee did not lock or give way. On physical examination, a consistent and large, orange-sized mass could be seen and palped. Lachman’s, McMurray’s, and Apley’s tests were negative, and the range of motion was 0 - 110º. Magnetic resonance showed that the mass was multi-lobulated with thin septations and surrounded the medial collateral ligament (Figures 2, 3, 4). Through a medial arthrotomy (Figure 5), the cyst was excised intact with its correspondent meniscus (Figure 6). The specimen measured 50 x 40 x 40 mm and contained clear gelatinous material. A split retinacular graft was performed to fulfil the capsule failure. Histological examination showed chronic inflammation without malignancy. The patient was ordered to wear a brace with partial weight bearing for two weeks. Rehabilitation occurred uneventfully. After a 2-year follow-up, the patient had full range of articular motion with no recurrence.

DISCUSSIONThe etiology of meniscal cysts is controversial. Many authors advocate that trauma, chronic infection, hemorrhage, and mucoid degeneration may lead to the development of these entities9. Because the fluid found in meniscal cysts is similar to sinovial fluid, the prevailing view is that cysts form from joint fluid that is forced through a peripherally extended meniscal tear and accumulates outside the joint capsule10. Pain is most likely related to the associated meniscal tears, but discomfort may also be due to stretching of the knee capsule and other parameniscal soft tissues11. The mass may be multiloculate and demonstrate thin internal septations, and its consistency may vary from soft and fluctuant to firm or bone-hard. MRI is preferred for evaluating meniscal cysts6,12 because it shows structures such as the menisci, cartilage and ligaments and is the most effective modality to evaluate soft-tissue masses. The differential diagnosis for soft-tissue masses of the knee should include sinovial cyst formation, bursal fluid collections, ganglion cysts, severe degenerative changes with osteophytic spurring and soft-tissue masses such as pigmented villonodular sinovitis, lipoma, hemangioma and sarcomas9. Meniscal cysts tend to recur after aspiration or simple resection6. Therefore, open or arthroscopic intra-articular surgery to treat the underlying meniscal tear is necessary for successful therapy13–15. In conclusion, distinguishing meniscal cysts from other cystic lesions is important because meniscal cysts more often require surgery. In our case, the uncommon combination of mass size and location associated with the gender and age of the host led us to report it.