After the influenza A H1N1 epidemics, the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has increased worldwide. The goal of respiratory ECMO support is to improve hypoxemia and hypercapnia, allowing protective mechanical ventilation to avoid further ventilator-associated lung injury (1). The current literature supports improved outcomes using ECMO in severe lung injury patients. In Brazil, few hospitals are able to provide respiratory ECMO support, and there is no transfer system (2).

The aim of this manuscript was to present and discuss two cases of severe respiratory failure supported with ECMO.

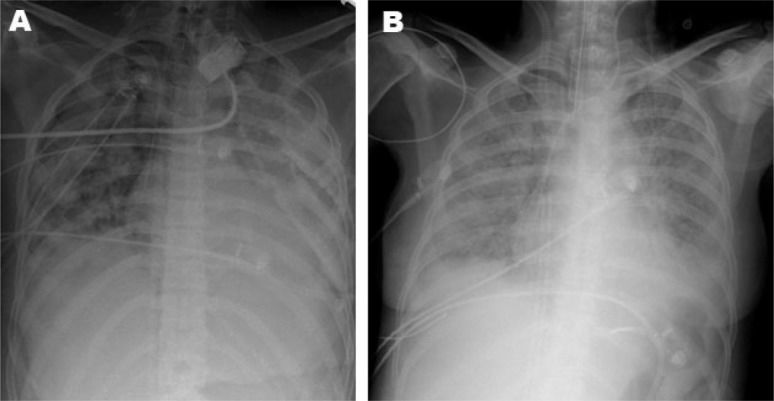

CASE DESCRIPTION 1A previously healthy 27-year-old man was admitted to a tertiary hospital in Guarulhos, São Paulo, with a diagnosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Three days later, his clinical status deteriorated, and mechanical ventilation was initiated due to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. Prone positioning and alveolar recruitment were attempted without success. Pneumothorax with a bronchopleural fistula complicated the clinical status, and the ECMO team from Hospital das Clínicas, São Paulo, Brazil, was called. A team consisting of one physician, one intensive care fellow, one registered respiratory therapist, and one registered nurse was sent to assess the patient. During the evaluation, the patient was found to have sustained pulse oximetry of 52%, an arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) of 43 mmHg and an arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) of 142 mmHg, with an inspired fraction of oxygen (FiO2) of 1 and optimized mechanical ventilation. There were no signs of hemodynamic compromise. Venous-venous ECMO support was initiated. The initial parameters were set at an oxygen flow (sweeper) of 6 L/min and a blood flow of 6 L/min. Ventilation was adjusted to pressure control mode, with a peak inspiratory pressure of 20 cmH2O, a positive end-expiratory pressure of 10 cmH2O, a respiratory rate of 10 breaths per minute and an FiO2 of 0.3. After stabilization, the patient was transferred to Hospital das Clínicas 27 km away in an ICU ambulance transport. The entire process, from initial call to arrival at Hospital das Clínicas, lasted 10 hours. The clinical and arterial blood gas data during the ICU stay are shown in Table 1. A chest radiograph is shown in Figure 1a.

Clinical data and arterial blood gases (Case 1).

| Data | Pre-ECMO | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| Ventilatory mode | PCVI) | PCVI) | PCVI) | PCVI) |

| Peak pressure (min–max) - cmH2O | 25 | 22 | 24 | |

| PEEP (min–max) - | 12 | 10 | 10 | |

| cmH2O £) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | |

| FIO2 (minmax) ¥) | 20–54 | 20-22 | 20-24 | |

| Respiratory rate (min–max) - breaths/min ECMOJ) | 3.3–6.4 | 4.49-4.79 | 4.58-7.9 | |

| Blood flow (min–max) - L/min | 10 | 6-10 | 8 | |

| Sweeper flow (min–max) - L/min | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| FIO2 | ||||

| Routine blood gas | 48.5 | 44.8 | 57 | |

| PaO2 - mmHg | 40.3 | 44.3 | 22.6 | |

| PaCO2 - mmHg | 8.4 | -6.5 | -13.3 | |

| SBE - mEq/L ∗) | 7.51 | 7.27 | 7.30 | |

| pH | ||||

| Patient data | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| SAS (min–max)#) | 2.75 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Lung injury score “) | 8 | 18 | 19 | |

| Total SOFA score 1) | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Respiratory SOFA | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Cardiovascular SOFA | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Hematological SOFA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Hepatic SOFA | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| Neurological SOFA | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Renal SOFA |

SOFA denotes sequential organ failure assessment. This score is used to diagnose and quantify organ failure, and it ranges from 0 to 24.

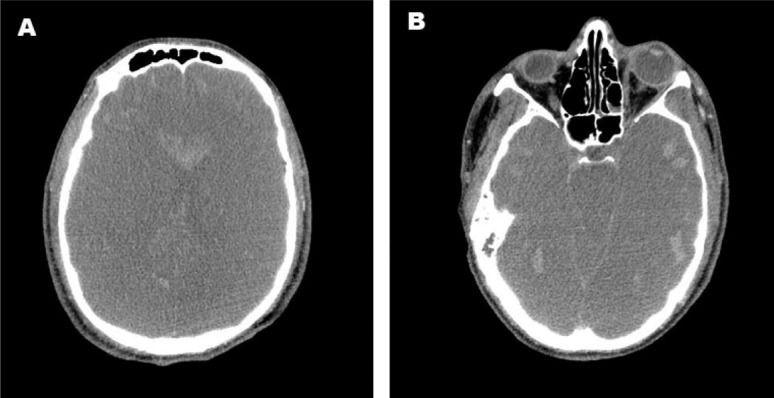

Twenty-four hours after arrival at Hospital das Clínicas, the patient's pupils became bilaterally dilated, and he lost brainstem reflexes in the absence of sedation, a clinical finding compatible with brain death. An apnea test was performed while the patient was normothermic with a mean arterial blood pressure of 86 mmHg by setting the ECMO to provide a pulse oximetry of at least 90% with the lowest sweeper flow setting. Mechanical ventilation was withdrawn, and continuous oxygen was supplied through the tracheal tube to prevent hypoxia. Close monitoring for respiratory movements was performed for 10 minutes. An arterial blood analysis was performed before and after the test to detect an increase in PaCO2 (Table 2). The neurological tests were repeated six hours later according to the Brazilian laws regulating the diagnosis of brain death. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography indicated cerebral circulatory arrest, and computed tomography showed diffuse brain edema, brainstem herniation, and multiple foci of hemorrhage (Figure 2). Thus, ICU support was withdrawn.

Arterial blood gases during the apnea test in patient 1.

| 1° test | 2° test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| pH | 7.303 | 7.072 | 7.319 | 7.141 |

| PaO2 | 67.0 mmHg | 61.2 mmHg | 100.3 mmHg | 66.3 mm Hg |

| PaCO2 | 50.3 mmHg | 87.3 mmHg | 44.4 mmHg | 73.0 mm Hg |

| Saturation | 90.5% | 77.1% | 97.0% | 84.2% |

| Bicarbonate | 24.3 mmol/L | 24.9 mmol/L | 22.3 mmol/L | 24.3 mmol/L |

| SBE∗) | -2.6 mmol/L | -7.5 mmol/L | -3.9 mmol/L | -6.3 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 21 mg/dL | 24 mg/dL | 25 mg/dL | 24 mg/dL |

A 42-year-old female with a previous history of illicit drug use was admitted to a tertiary hospital in Guarulhos, São Paulo, at 10 days postpartum with the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Five days later, she developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and was transferred to the ICU. Two days later, her respiratory status deteriorated, with persistent hypoxemic and hypercapnic respiratory failure, and the ECMO response team from Hospital das Clínicas was called.

The patient had a peripheral oxygen saturation of 80% and a PaCO2 of 80 mmHg without hemodynamic compromise. Mechanical ventilation was set at a PEEP of 10 cmH2O, an FiO2 of 1, and a peak pressure of 35 cmH2O. Venous-venous ECMO support was initiated. Her blood gas parameters improved after ECMO support, and the patient was transferred by helicopter. The entire process, from the initial call to arrival at Hospital das Clínicas, lasted four hours. The chest radiograph acquired in our hospital is shown in Figure 1b.

During the first two days after cannulation, the patient was sedated with propofol and fentanyl, with a Sedation-Agitation Scale ranging from 2 to 5 due to drug abstinence. Ventilation was set in pressure support mode with a positive-end expiratory pressure of 10 cmH2O, a pressure support of 8 cmH2O, and an FiO2 of 0.3. The ECMO settings were adjusted to achieve a PaO2>50 mmHg.

The patient improved gradually (Table 3), and after seven days of extracorporeal support, she was awake and cooperative. Daily weaning tests from ECMO support were conducted in accordance with our criteria for ECMO discontinuation. ECMO was stopped nine days after initiation. Mechanical ventilation was discontinued two days later. The patient was discharged from the hospital 33 days after admission with no functional disability.

Clinical data and arterial blood gases (Case 2).

| Data | Pre-ECMO | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 5 | Day 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||

| Ventilatory mode | PCVI) | PCVI) | PCVI) | PSV2) | PSV2) |

| Peak pressure (min–max) - cmH2O | 25 | 2515 | 2515 | 2013 | |

| PEEP (min–max) - cmH2O £) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| FIO2 (min–max) ¥) | 15-21 | 19-28 | 16-36 | 14-42 | |

| Respiratory rate (min–max) - breaths/min ECMOJ) | 3.02- | 4.48-6.62 | 4.05- | 3.67- | |

| Blood flow (min–max) - L/min | 5.33 | 6 | 5.08 | 3.84 | |

| Sweeper flow (min–max) - L/min | 6–7 | 1.0 | 3-4.5 | 0.5 | |

| FIO2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Routine blood gas | 66.3 | ||||

| PaO2 - mmHg | 51.4 | 42.4 | 52 | 79.8 | |

| PaCO2 - mmHg | 40.6 | +1.9 | 33 | 57.3 | |

| SBE - mEq/L ∗) | -0.6 | 7.41 | +6.1 | +6.6 | |

| pH | 7.39 | 7.41 | 7.38 | ||

| Patient data | 2–6 | ||||

| SAS (min – max)#) | 2 | 2.5 | 3-5 | 4 | |

| Lung injury score “) | 3 | 6 | 2.75 | 2.5 | |

| Total SOFA score 1) | 6 | 4 | 8 | 4 | |

| Respiratory SOFA | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Cardiovascular SOFA | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Hematological SOFA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hepatic SOFA | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Neurological SOFA | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Renal SOFA | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SOFA denotes sequential organ failure assessment. This score is used to diagnose and quantify organ failure, and it ranges from 0 to 24.

The use of ECMO in adult patients has increased after the influenza A H1N1 outbreak. During the H1N1 epidemics, two observational studies reported a mortality rate of 20% with ECMO support compared to the expected 50% mortality in conventionally supported patients (3,4). Additionally, in patients with severe lung injury, the CESAR trial showed that 63% of patients supported with an ECMO-including strategy survived without disability for six months compared to 47% of those allocated to conventional support (1).

Patient transferMost studies involving transfer to referral centers during ECMO opted to transfer the patient in conventional mechanical ventilation before starting ECMO support (1,3). However, this type of transferinvolves considerable risk, and deaths have been described during the process (1). Conversely, previously published data show the safety and feasibility of the inter-hospital transport of critically ill adults under ECMO support (5,6). After implementing a protocol for the safe transport of adults on ECMO, Forrest et al. described the transportation of 40 patients without deaths or major morbidity (6). In another study, transportation under ECMO support was associated with fewer episodes of hypoxia compared to patients transported under conventional ventilation (7). In both of our cases, we chose to initiate ECMO support before patient transfer to assure safer transport. There were no adverse events during transportation between the hospitals.

The optimal timing for ECMO initiation is not well established. Both of the patients described in this report were transferred from the same hospital in the city of Guarulhos. In the first case, ECMO was started several days after intubation, while the second patient was cannulated early after the diagnosis of severe respiratory failure. Because there is no organized referral system between our services, it is reasonable to presume that the first successful transport may have encouraged faster contact for the second patient. As previously reported by Forrest et al. (6), we believe that the development of a referral and transfer program is associated with faster ECMO initiation, safer transportation and, possibly, a higher rate of survival.

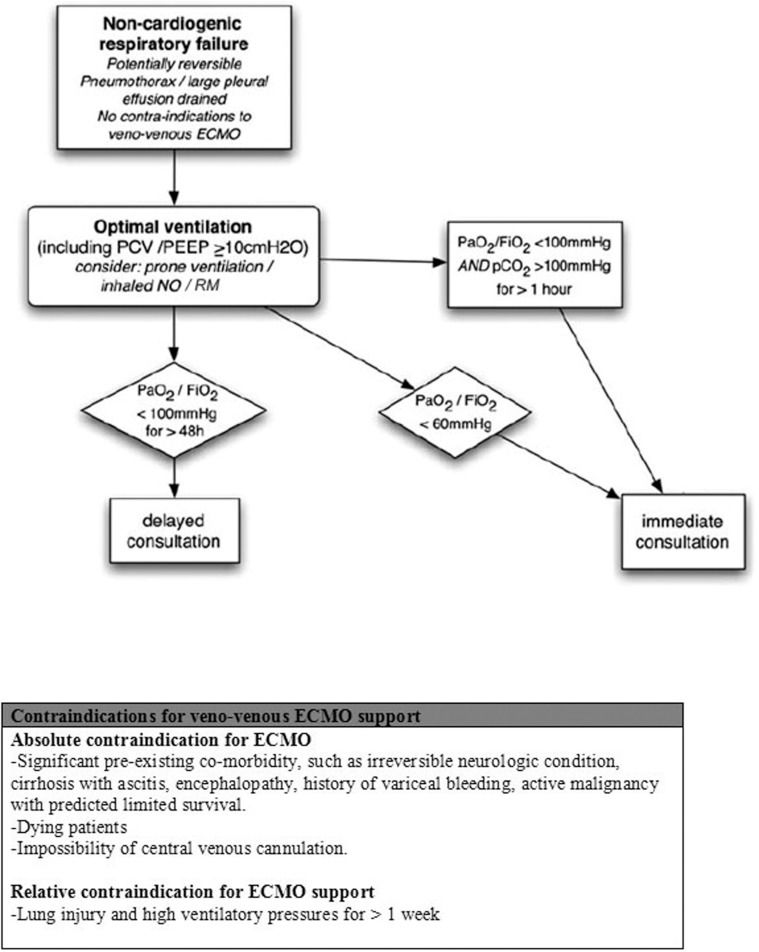

We propose the algorithm described in Figure 3 to create a transfer program for ECMO patients. As described in this report, earlier ECMO initiation is most likely associated with higher rates of survival. Therefore, we believe that a low threshold of hypoxemia despite optimal therapy should be sufficient to trigger an ECMO specialist consultation. The classical criteria for ECMO initiation should not be used as a trigger for consultation because it may adversely hinder support. In the presence of critical but reversible lung injury with no contraindication for extracorporeal support, an ECMO team (composed of two physicians and one registered nurse) would be responsible for the evaluation of the patient on location and, if indicated, ECMO support initiation. Because ECMO is a highly complex technique that involves high costs, constant personnel training and high complication rates (8), referral centers should be reserved for tertiary care centers only.

Brain death diagnosis during ECMO supportNeurological injury is common in ECMO-supported patients. It is uncertain whether the extracorporeal support may precipitate injury or if the patient's morbid condition is the only responsible factor (9). A study of 295 patients from the ELSO registry for whom ECMO was used to support cardiopulmonary resuscitation reported brain death in 28% of non-survivors (10) More recently, ECMO support to maintain potential organ donors has been used to increase the donor pool (11).

Performing an apnea test in ECMO-supported patients is a major challenge because ECMO support is able to maintain normal blood gases in apneic patients. In case 1, we decided to disconnect the patient from the ventilator and then set the sweeper flow to the lowest level necessary to achieve a pulse oximetry of 90%. Respiratory movements were monitored, and blood gas analyses were obtained before and 10 minutes after a stable sweeper flow was initiated to detect an increase in the carbon dioxide partial pressure. Muralidharan et al. (12) reported three cases of possible brain death in ECMO patients in which the apnea test was not performed due to the lack of standardized procedures. However, they suggested that patients should remain connected to the ventilator under continuous positive airway pressure with a PaCO2 between 35–45 mmHg. Subsequently, they suggested that the sweeper flow be set to the minimum value compatible with normal pulse oximetry before the test. We adopted a similar procedure.

ECMO is a specialized technique and a lifesaving measure when other rescue therapies have failed. The treatment of patients under ECMO support must be performed in referral centers with a trained ECMO team. The transfer of patients seems plausible and safe. Despite recent advances and continuous training, there are still many uncertainties in the management of this specific population.

Conflicts of interests: The authors received ECMO membranes as a donation from MAQUET Cardiopulmonary of Brazil.

Participants of ECMO Group:

Marcelo Park

Eduardo Leite Vieira Costa

Alexandre Toledo Maciel

Pedro Vitale Mendes

Leandro Utino Taniguchi

Fernanda Maria Queiroz Silva

Andre´ Luiz de Oliveira Martins

Edzangela Vasconcelos Santos Barbosa

Raquel Oliveira Nardi

Michelle de Nardi Igna´cio

Cla´udio Cerqueira Machtans

Wellington Alves Neves

Adriana Sayuri Hirota

Marcelo Brito Passos Amato

Guilherme de Paula Pinto Schettino

Carlos Roberto Ribeiro Carvalho

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Mendes PV, Moura E, Park M, Barbosa EV, Hirota AS, Scordamaglio PR, Ajjar FM, Costa EL and Azevedo LC provided medical support to the patients. Mendes PV and Moura E wrote the manuscript. Barbosa EV, Hirota AS, Scordamaglio PR and Ajjar FM were responsible for data collection. Costa EL, Azevedo LC and Park M critically reviewed the manuscript.