Spontaneous thrombosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an uncommon condition. Chronic thrombosed AAA are related to occlusive iliac disease and often present with intermittent claudication.1,2 However, the symptoms related to expansion of the aneurysm and risk of rupture must be considerable, even in thrombosed aorta.1 We present our experience with three consecutive cases of chronic thrombosed aneurysms with different clinical manifestations. The current understanding of chronic thrombosed aneurysm pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment are reviewed.

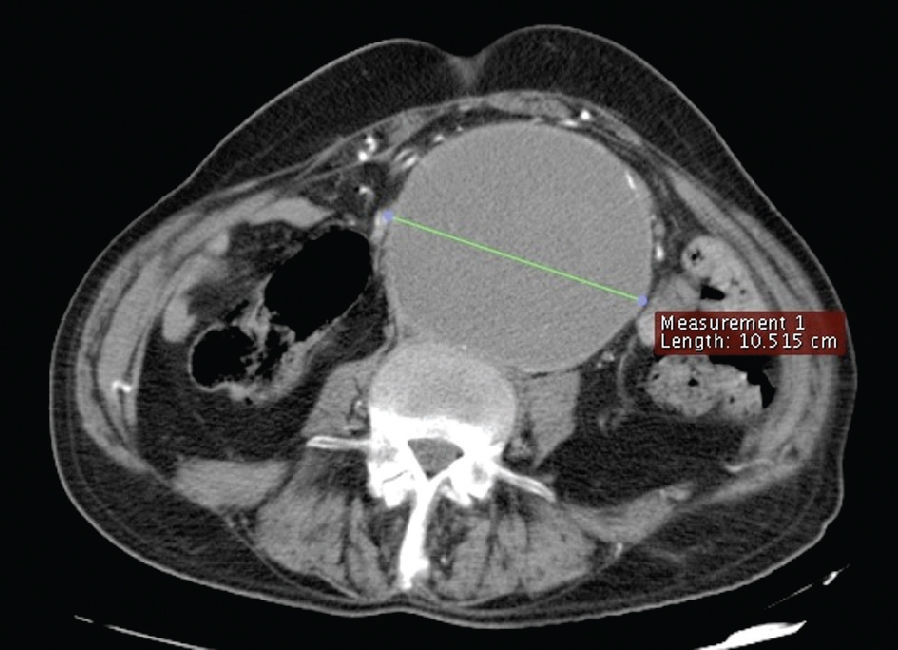

REPORTCase 1: A 71-year-old man entered our emergency department presenting with abdominal pain that had lasted for six months and had worsened in the last week. His past medical history revealed hypertension, tabagism, dyslipidemia and epilepsy. His left lower leg was amputated 11 years earlier, after an accident with chemicals; the right lower leg of the patient was also amputated after an episode of acute ischemia six years before that date. His physical examination revealed a painful, palpable pulsatile mass extending from the mesogastrium to the infraumbilical area. There was no femoral pulse, but the stumps and buttocks had a normal temperature. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a thrombosed infra-renal aneurysm with a maximum transverse diameter of 10.5 cm (Pictures 1 and 2).

After cardiac evaluation, an elective laparotomy was performed. The surgery revealed an inflammatory aortic aneurysm with clearly visible local wall necrosis (Picture 3). After clamping the aorta, the aneurysm sac was incised, releasing a great volume of thrombosed and liquefied clots under significant pressure. The aorta and both iliac common arteries were sutured, and no bypass was performed. The postoperative course was unremarkable, and the patient was sent home on the sixth postoperative day. He continued with ambulatory consultations. On the 40th postoperative day, the patient returned to the emergency room in a septic state with abdominal pain, ascites and circulatory shock. The patient expired in the emergency room before surgery could be performed, despite aggressive attempts to resuscitate him. The post mortem examination revealed diffused peritonitis as a consequence of mesenteric ischemia and perforation of the small intestine, associated with pancreatitis. There was neither an aortic stump blow-out nor a colon ischemia.

Case 2: A 57-year-old man sought medical attention for evaluation of spontaneous ischemic necrosis of the fifth toe of the right foot. He denied symptoms of abdominal pain, but his general condition was extremely poor. Notable parts of his past medical history included hypertension, tabagism, coronary heart disease and stroke. His physical examination indicated a 4-cm palpable pulsatile mass in megogastrium. There were no femoral or distal pulses. A CT scan of the abdomen and lower extremities revealed a thrombosed 3.5-cm infra-renal AAA with occlusive arterial disease of the iliac and femoral arteries (Picture 4). Deep femoral arteries were patent. A duplex scan of the carotid arteries showed an occlusion of the right internal carotid artery and no significant stenosis in the left internal carotid artery.

Cardiac evaluation had deemed him as high risk for open repair. An axillobifemoral bypass using an 8-mm Dacron graft was performed under general anesthesia. The patient was sent home on postoperative day 8. The patient is still been attentively observed to check the aneurysm.

Case 3: A 58-year-old man sought medical attention for evaluation of an infected ulcer in the calcaneous and the dorsal aspect of the left foot. He denied any symptoms of abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for diabetes, hypertension and 38 years of smoking. Clinical examination revealed the absence of femoral pulses. A CT scan of the abdomen and lower extremities detected a 3.0-cm infra-renal AAA and a thrombosed 2.5-cm right common iliac artery aneurysm with occlusive arterial disease of the external bilateral iliacs (Picture 5). Common femoral arteries were evident.

An aortic-iliac-femoral bypass was successfully performed. Following a prolonged recovery, due to an uncontrolled infection of the left foot, a transtibial amputation was performed. The patient was discharged and sent home on postoperative day 25.

DISCUSSIONSchumacker3 reported the first thrombosed AAA in 1959, and Janetta and Roberts1,4 reported the first successful revascularization procedure in 1960. The spontaneous thrombosis of aortic aneurysm is rare.1,5 Acute thrombosis often presents with limb ischemia or neurological deficits and carries a mortality rate up to 50%, as reviewed by Hirose et al.2,6 There are only 51 cases of acute thrombosis of AAA reported in the literature.1–13

Manifestation of chronic thrombosis AAA is a rare but well-recognized issue in clinical practice and is present in patients with intermittent claudication. Most of the literature that references rupture of chronic thrombosis of AAA is linked to deliberate thrombosis of the aorta, followed by extra-anatomic bypass.1,5,7,8 Only three cases of rupture of a previous spontaneously thrombosed AAA have been reported.1–3

Several factors appear to be associated with AAA thrombosis.9 Surgical manipulation, trauma, fever, thromboembolic disease, dehydration, hyper-coagulation, hypotension, atrial fibrillation, neoplasm, intraplaque hemorrhage, dislodgment of mural thrombus, iliac artery occlusive disease and AAA rupture have already been described.9 However, for thrombosed aneurysm, obstructive iliac disease plays the most important role in chronic manifestation.

The prevalence of AAA in the population with symptomatic peripheral vascular disease ranges from 4% to 10%.10–13 The optimal procedure for managing an AAA associated with occlusive disease is endoaneurysmorrhaphy with inline aortic reconstruction, as in our third case. Nevertheless, in high-risk patients with severe cardiac, respiratory or renal disease, extra-anatomic axillobifemoral bypass is an acceptable alternative.8 This procedure is advantageous because it is less invasive, avoids major abdominal surgery and can be performed with regional anesthesia.9 However, late rupture of a previously thrombosed aneurysm must be considered. Ricotta and Kirshner5 reported a case in which a patient with a thrombosed aneurysm died of a rupture less than six months after an axillobifemoral bypass, and Leke2 reported a case in which a patient died of a rupture seven months after an extra-anatomic bypass.

In the past two decades, some authors have advocated a non-resective approach to treating AAAs in high-risk patients that combines extra-anatomic revascularization of the lower extremities with ligation or endovascular occlusion of the aneurysm.2,14 The purpose of such a procedure is to induce thrombosis and decrease the risk of rupture. However, the operative mortality in these high-risk patients ranges from 13% to 31%.8,15 In our first case, although the surgical procedure was successful, the patient died in the second postoperative month due to mesenteric ischemia. There was no clear association of the aortic ligation and the mesenteric ischemia, since the post mortem examination revealed neither an aortic thrombosis nor the proximal propagation of aortic thrombus. We believe that the systemic atherosclerotic disease present in this patient was the major factor that complicated his recovery.

Late rupture of surgically induced thrombosed AAA has been reported.1,5,7 Schwartz et al.15 analyzed 13 patients with AAA thrombosis and extra-anatomic bypass and reported a delayed aneurysmal rupture of 15% in only 6 months. These reports emphasize the concept that the thrombosis of an abdominal aortic aneurysm does not absolutely preclude rupture.7 Another technique that is described is a retroeritoneal approach using ligation of the aorta and proximal and distal ligation of the aneurysm (exclusion), coupled with an aortic bypass. Resnikoff16 related a rupture incidence of 0.8% over ten years. We opted for an extra-anatomic bypass in our second case because the patient had a small aortic aneurysm (3.5 cm) and was at high operative risk. However, the assumed risk for late rupture implies that close follow-up is imperative to detect any expansion of the aneurysm.

Our third patient had an infra-renal AAA and a thrombosed 2.5-cm right common iliac artery aneurysm associated with occlusive arterial disease of both external iliacs. Although it was not considered a true thrombosed abdominal aortic aneurysm, the outflow obstruction resulted in a pressurization of the iliac aneurysm similar to the “water hammer” effect. We believe the physiopathology of both obstructions are similar and because of this a definitive surgery treatment is needed. Schurink et al.17 studied the effect of thrombus on aneurysm wall pressure and concluded that thrombus within the aneurysm does not reduce the pulse pressure near the aneurysm wall and, consequently, does not reduce the risk of rupture. Furthermore, rupture could occur if a thrombosed sac continued to be pressurized by collateral perfusion.1,17 The symptoms of our first patient demonstrate clearly that a chronic thrombosed aneurysm can be pressurized. The local wall necrosis and the inflammatory aspect of the aneurysm were characteristic of an imminence of rupture (Picture 2). Takagi et al.18 measured and compared the intraluminal and intrathrombotic pressure in three points of a thrombosed abdominal aortic aneurysm and found only a 1%–5% decrease in the mean intrathrombotic pressure relative to intraluminal pressure. These authors concluded that the mural thrombus of an aneurysm does not significantly decrease the pressure on the aneurysm wall, even in a thrombosed aneurysm. Recently, Dalal et al.1 concluded that the new concept of endotension following endovascular repair of aneurysms (EVAR) can also be applied to thrombosed aneurysm. This concept describing pressurization of the aneurysm wall demonstrates the need for surveillance to identify continued aneurysm expansion when a non-resective approach is used to treat these thrombosed aneurysms, as in the case of EVAR.

CONCLUSIONChronic thrombosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm can be demonstrated not only as occlusive iliac disease but also as ruptured or expanded AAA. We conclude that the thrombosis of the aneurysm does not protect the aortic wall from pressurization and the risk of rupture. This reinforces the concept that the optimal management for AAA associated with occlusive aortic-iliac disease is endoaneurysmorrhaphy with inline aortic reconstruction. In exceptional cases of high-risk patients, in which extra-anatomic bypass must be chosen, surveillance for the expansion of the aneurysm must be diligently performed during the follow-up process.