Urinary lithiasis is a common disease. The aim of the present study is to assess the knowledge regarding the diagnosis, treatment and recommendations given to patients with ureteral colic by professionals of an academic hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:Sixty-five physicians were interviewed about previous experience with guidelines regarding ureteral colic and how they manage patients with ureteral colic in regards to diagnosis, treatment and the information provided to the patients.

RESULTS:Thirty-six percent of the interviewed physicians were surgeons, and 64% were clinicians. Forty-one percent of the physicians reported experience with ureterolithiasis guidelines. Seventy-two percent indicated that they use noncontrast CT scans for the diagnosis of lithiasis. All of the respondents prescribe hydration, primarily for the improvement of stone elimination (39.3%). The average number of drugs used was 3.5. The combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids was reported by 54% of the physicians (i.e., 59% of surgeons and 25.6% of clinicians used this combination of drugs) (p = 0.014). Only 21.3% prescribe alpha blockers.

CONCLUSION:Reported experience with guidelines had little impact on several habitual practices. For example, only 21.3% of the respondents indicated that they prescribed alpha blockers; however, alpha blockers may increase stone elimination by up to 54%. Furthermore, although a meta-analysis demonstrated that hydration had no effect on the transit time of the stone or on the pain, the majority of the physicians reported that they prescribed more than 500 ml of fluid. Dipyrone, hyoscine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids were identified as the most frequently prescribed drug combination. The information regarding the time for the passage of urinary stones was inconsistent. The development of continuing education programs regarding ureteral colic in the emergency room is necessary.

Urinary lithiasis is a common disease that affects more than 12% of the population (1). Renal colic affects approximately 1.2 million people annually and accounts for 1% of emergency room care and 1% of all hospitalizations (2). The total annual medical expenditures for renal stones in the United States were estimated at 2.1 billion US dollars in 2000 (3).

The emergency room physician is often responsible for the care and initial evaluation of patients with nephrolithiasis. In addition, emergency room physicians are responsible for handling and referring nephrolithiasis patients for specialized evaluation when necessary.

Several studies have been conducted to standardize the best practices for the management of patients with ureteral stones, and attending physicians should be aware of the best practices.

The Hospital Universitário (HU-USP) is a referral hospital for disorders requiring treatment of medium to high complexity. The medical team is directly involved in education and training at the graduate and postgraduate levels.

Approximately 600 patients are admitted annually at the Emergency Room of the Hospital Universitário (ER-HU-USP) under the diagnosis of renal colic.

The present study was designed to assess the knowledge and practices regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and recommendations given to patients with ureteral colic by professionals of the Emergency Room of the Hospital Universitário (ER-HU-USP).

MATERIALS AND METHODSSixty-five physicians working at the Emergency Room of the Hospital Universitário (ER-HU-USP) were invited to participate in this study, and four physicians refused to participate. All of the respondents completed a consent form and were assured of anonymity.

After completing the questionnaire, the respondents received papers with information about the topics covered (4–7).

The respondents were asked about how long they had been practicing medicine since the end of their residency, previous experience with ureterolithiasis guidelines and how they manage patients with ureteral colic in regards to diagnosis, treatment and the information provided to the patients.

The study protocol was approved by the Internal Review Board (IRB) of the Hospital Universitário (HU-USP). The data were analyzed with the chi-square test using SPSS version 17.

RESULTSOf the 65 physicians who were invited to participate in the present study, 61 (93.9%) completed the questionnaire. Thirty-six percent were surgeons, and 64% were clinicians. The average time since the completion of their medical residency was 13.2 years (the range was 1 to 28). Forty-one percent of the physicians interviewed reported previous experience with standards of care for patients with ureteral colic. The average numbers of patients attended with renal colic were 11.2 per week per surgeon and 2.2 per week per clinician in the Emergency Room of the Hospital Universitário (ER-HU-USP).

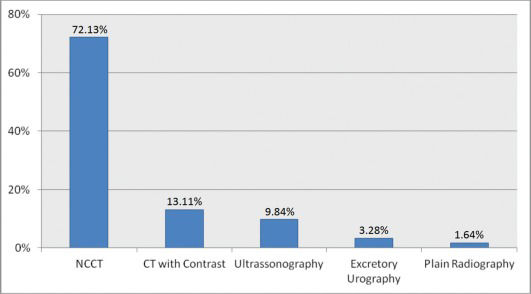

Seventy-two percent of the interviewed staff indicated that a noncontrast CT scan (NCCT) is the method of choice for the diagnosis of ureteral lithiasis.

All of the respondents prescribed hydration. The reported reasons for fluid hydration were improvement of the rate of stone elimination (39.3%), rehydration (31.2%), pain control (9.8%) and other reasons (19.7%). Fifty percent of the respondents prescribed more than 500 ml of fluid, and the majority of the physicians who believed that hydration may influence stone elimination (i.e., 66.6%) prescribed more than 500 ml.

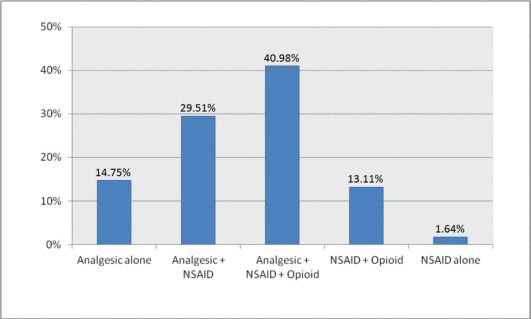

The majority of the physicians (93%) used a combination of drugs for pain control. The average number of drugs was 3.5. The most common combination of drugs was analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and opioids (40.98%), and the majority of physicians (86.9%) used hyoscine alone or with other drugs.

The interviewed staff reported 17 different prescription combinations. For analytical purposes, we grouped the medications into three classes: analgesics, NSAIDs, and opioids. Figure 2 shows the combinations of drugs that were prescribed.

Regarding the information about the likelihood of spontaneous ureteral stone elimination provided to the patients, the average percentages were 84.9% for stones up to 4 mm and 45% for stones >4 mm. The estimated average times for stone elimination were 4.7 days for stones smaller than 2 mm, 6.7 days for 2-4 mm stones, and 27 days for 4-6 mm stones. Eighty percent of the respondents referred patients to follow-up with an urologist, and 87.5% of these physicians recommend the follow-up within a period of 15 days (12.5% referred patients after 15 days).

When analyzing the respondents by specialty, there was a difference regarding the drugs that were prescribed for pain control. The combination of NSAIDS and opioids was reported by 54% of the physicians, and some cases also included the combination of other drugs. Specifically, 59% of the surgeons and 25.6% of the clinicians prescribed a combination of NSAIDS and opioids (p = 0.014). Opioids were prescribed by 72.7% of the surgeons and 48.7% of the clinicians (p = 0.06). Only 21.3% of the respondents prescribe alpha blockers for patients with ureteral stones (60.3% were surgeons).

DISCUSSIONBased on the results of a study conducted by Phillips and colleagues in 2009 (8), the present study aimed to assess the knowledge of the emergency room staff of a university hospital regarding the management of ureteral calculi.

The present study has several particularities. In Brazil, physicians with a specific focus on emergency medicine do not exist. In almost all emergency rooms, the general surgeon is responsible for the first consultation of all of the patients with renal colic. In the present study, we evaluated the emergency room staff of a University Hospital (HU-USP). The staff is deeply involved in the teaching and tutoring of medical students and residents (general surgery and general medicine), which highlights the importance of addressing emergency medicine knowledge, access to guidelines and the continuing education of the staff to improve the quality of information provided to medical students, residents and patients.

To reduce the selection bias, which was one of the limitations of the Phillips study, all of the physicians were personally interviewed by three medical doctors. The majority (93.9%) of the invited attending physicians responded to the questionnaire.

Although 41% of the interviewed physicians reported previous experience with standards of care for patients with ureteral colic, this experience had little impact on several habitual and widespread management practices. The adoption of evidence-based clinical protocols not only results in more accurate diagnoses but also improves cost-effectiveness and reduces diagnosis delay.

Only 21.3% of the respondents indicated that they prescribed alpha blockers in daily practice. According to a meta-analysis with 900 patients, the use of alpha blockers may increase the chance of spontaneous stone elimination by up to 54%. The guidelines of the American Urological Association and the European Association of Urology suggest the use of alpha blockers for ureteral colic (9).

Possible explanations for the low percentage of attending physicians who prescribed alpha blockers in the present study are the combination of the high cost of these drugs, their unavailability for free distribution in the public health system and the economic profile of the study population. In addition, the limited use of alpha blockers may be a result of the restricted publication of medical expulsive therapies in urological journals and guidelines that might not be well known among physicians of other specialties. Sixty-four percent of the respondents completed their training more than five years ago, which could also contribute to the low prescription of alpha blockers because the most recent guideline was published in 2007 (5,9).

When analyzing the choice of diagnostic tests, we observed that the majority (72%) of the physicians indicated NCCT as the method of choice for the diagnosis of renal stones (Figure 1).

Previous reports compared the accuracy of CT scans with those of other radiological methods. The CT scan is more sensitive (94%-97%) in comparison with ultrasound (19%) (10). Importantly, the CT specificity can be as high as 98% (11,12).

Although ultrasound can be useful in patients for whom it might be necessary to avoid exposure to radiation and contrast agents, it is limited by low sensitivity (19%), difficulty in the evaluation of obese patients, limited visualization of mid-ureteral stones and inadequate imaging of the renal collecting system (10,11).

Plain radiography has a sensitivity that ranges from 45-60% (13). Factors such as lack of bowel preparation, plain abdominal radiography position, and technical acquisition may negatively influence the quality of the image (12,13). Excretory urography has a lower sensitivity (64-88%) and specificity (92-94%) compared with those of a CT scan.

Some physicians argue that CT can be expensive and time consuming (12). However, the increased use of the modern multichannel CT, which has a faster acquisition and the capability of identifying additional diagnostics with fewer studies, has improved CT cost-effectiveness (13).

Although a recent meta-analysis showed that hydration had no effect on the transit time of the stone, levels of pain or the reduction of analgesics, the majority of the physicians at the ER-HU-USP reported prescribing more than 500 ml of fluid. Interestingly, the primary reason was to improve stone elimination (4).

Compared with the results obtained by Phillips, significant differences were obtained regarding pain management, alpha blocker prescription. Most respondents (86.9%) indicated the use of combined regimens of analgesics for the relief of the pain caused by ureteral lithiasis. In contrast to the data indicated by Phillips in which 76% of emergency physicians used only one type of analgesic, the most frequently prescribed drug combination by the physicians in the present study was dipyrone, ER hyoscine, NSAID and opioids. Hyoscine and dipyrone are not commonly used in the USA. Philips data also indicated more alpha blocker prescription (58%).

Patients commonly ask about the necessary time for the spontaneous elimination of urinary stones and the chance of spontaneous clearance.

Miller and Kane reported a 95% rate of passage in 31 days for stones smaller than 2 mm, 83% in 40 days for stones between 2 and 4 mm and 50% in 39 days for stones larger than 6 mm [14]. Miller and Kane found that the average time for elimination was 8.2 days for stones less than 2 mm, 12.2 days for stones between 2 and 4 mm and 22 days for stones between 4 and 6 mm [14].

In the present study, the information regarding the time for the passage of urinary stones is inconsistent, especially in relation to stones with larger diameters.

The present study has several limitations. For example, the present study was based on self-completed questionnaires, and possible bias may be present. In addition, the small number of physicians may preclude major conclusions. However, the present study presents certain interesting data on the management of ureteral calculi in a university hospital. Even in academic hospitals involved in training and teaching, it is clear that continuing medical education programs are required to provide the best evidence-based clinical practice to patients with impact on costs, morbidity and treatment.

Based on the data collected at the Emergency Room of the Hospital Universitário (ER-HU-USP), the development of continuing education programs with emphasis on the dissemination of evidence-based knowledge among professionals dealing with ureteral colic at the emergency room is necessary.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSClaros OR and Silva CHW contributed to the interviews, literature review, data review, and article elaboration. Consolmagno H and Sakai AT contributed to the protocol elaboration and review. Freddy R contributed to the interviews. Fugita OEH contributed to the project orientation, protocol elaboration, article elaboration and review.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.