Primary Health Care (PHC) plays a pivotal role in the healthcare system as the initial point of contact for users and patients. In the healthcare area, claims are presented and managed through a web app. It also enables systematic analysis of emerging information to drive continuous improvement. The present objective was to describe the complaints filed at PHC in 2022.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted, examining complaints filed by patients in 2022. For inclusion of the complaints, it was established that it had to do with the treatment received by healthcare personnel and that was presented through the web app. Complaint texts signaling dissatisfaction with the information received were subjected to qualitative coding.

ResultsThe study involved 326 users who submitted a total of 358 complaints specifically related to treatment and information. The average age of the participants was 33.5 ± 16.2 years, and the majority were women (72.4 %, n = 236). In 2022, the Cumulative Incidence (CCI) was 55.2 complaints per 100,000 healthcare act and the Complaint Incidence Rate (CIR), defined as the number of complaints/1000 users/year, was 6.5. The prevalence of complaints related to information was 12.4 %. The main reasons for complaints about information were issues related to communication with the patient (79 %), followed by the patient's disagreement with the techniques applied by healthcare staff (17 %).

ConclusionsResults show us the fundamental characteristics of complaints in primary care with respect to the information received by health professionals, not allowing us to know where the authors can influence through interventions or training actions to try to improve.

Primary Health Care (PHC) is considered a fundamental part of the healthcare system, acting as the first point of contact for users and patients to access available health services.1–3 Primary Care Health Care defined as “essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound, and socially acceptable methods and technologies, made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford”.3 Conferences like the 2018 World Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana, Kazakhstan emphasize the active participation of healthcare system users and health services as a tool for continuous improvement of processes at the primary care level.4

User participation in the healthcare system is manifested through complaints and their management. Diverse Laws and Normative establishes cooperation and coordination among public health administrations, guaranteeing equity, quality, equality, and social participation in the national healthcare system.5,6 Currently, the strategic plans of healthcare organizations should focus on user satisfaction, as explained by the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) about the assessment of user opinions as an essential tool for total quality management.7 In this regard, patient care units are established to facilitate direct user participation through the circuit of complaints and suggestions, enabling the analysis of unmet expectations and needs of the population served.8 In this context, the Galician Health Law establishes the rights that influence the development of measures so that all centers, services, and healthcare facilities make suggestion and complaint forms available to users, as well as efficient procedures to receive written responses within established regulatory deadlines.9 This model incorporates various principles: strengthening traditional values, community orientation, strengthening equity and the role of the patient, ensuring comparative leadership, and ensuring economic sufficiency and regulatory viability.10–12 On the other hand, it is well-known that complaints provide a partial approach to user opinions.13

Complaints allow us to understand the impact of structural and organizational changes on users.14,15 Analysis of complaints helps us identify certain areas and improvements, in order to increase the quality of the services offered.16,17 In this context, the objective was to describe the complaints filed at the Primary Care level during the year 2022.

Materials and methodsStudy designA descriptive cross-sectional design was used to study complaints regarding information at the Primary care level reported by users in the healthcare area of Santiago and Barbanza in the year 2022. This study was conducted following the STROBE guidelines. The following secondary objectives were defined: Determine the prevalence and incidence of complaints regarding information received in this level of care attention and identify the characteristics of the claims in terms of type of complaint, and professional involved, as well as study the characteristics of the patients who presented these claims.

Population and sampleThis study was conducted in the healthcare area of Santiago and Barbanza, which had a reference population for primary care of 442,618 citizens in the year 2022, distributed across 46 municipalities, with a total of 76 healthcare centers, including local clinics.

Assuming that a user of the healthcare system who files complaints regarding the received information is likely to file more than one complaint per year and that they are also frequent users (defined as those who have more than 12 visits per year),18 the authors selected as the sample for the study the users who filed at least one complaint regarding information in 2022. During the year 2022, 326 users in the Santiago and Barbanza areas filed complaints about information received in primary care. All these complaints will be studied in the present project. To determine whether the differences found in the bivariate analyses according to the objectives were significant, a significance level of 5 % was established, with a confidence interval of 95 % for estimating the parameter. Assuming an expected prevalence of complaints regarding treatment received of 18 %,19 a significance level of 5 % with a confidence interval of 95 % for estimating the parameter, with a precision of 3 %, this sample of 326 users provided us with a statistical power greater than 90 % for estimation.

ProcedureTo achieve the objectives of the study, all complaints filed web app regarding the information received by primary care users were included.

Based on this web app, the Claims Management Unit of the Santiago and Barbanza Health Area generates a dataset for analyzing each complaint and providing a response. Therefore, this unit maintains a data registry for care and management purposes, which is used to perform analyses of the unit's own activities, as well as continuous improvement work.

To determine the number of contacts made by users who were part of the sample, as well as the services and units, both in primary care and hospital settings, that they interacted with during the years 2020 to 2022, a query was made to the Complex Analysis Information System (SIAC) of Galician Health Service (SERGAS).

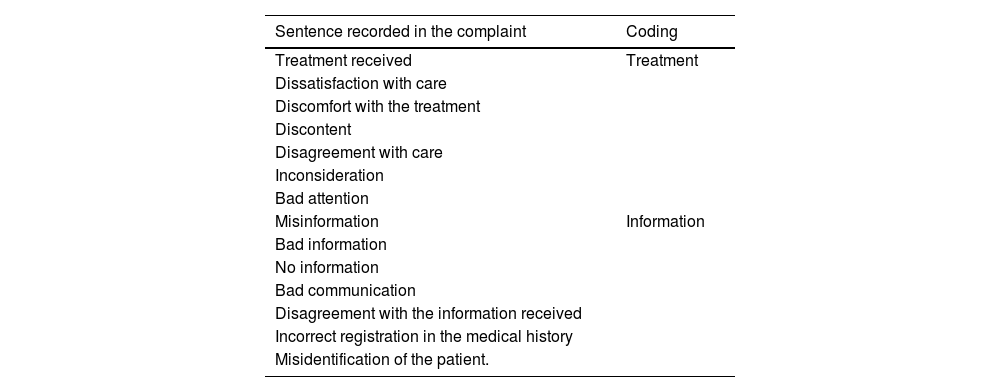

Statistical analysisThe varied expressions within the complaint texts signaling dissatisfaction with the information received were subjected to qualitative coding. Two independent researchers performed this coding, resolving any discrepancies through mutual agreement on classification. In this way, two types of reasons for the claim were generated: Disagreement with the treatment received and disagreement with the information received by the health professional who had cared for the complaining patient. The coding process adhered to the guidelines outlined in Table 1.

Coding of the qualitative aspects contained in the complaints.

| Sentence recorded in the complaint | Coding |

|---|---|

| Treatment received | Treatment |

| Dissatisfaction with care | |

| Discomfort with the treatment | |

| Discontent | |

| Disagreement with care | |

| Inconsideration | |

| Bad attention | |

| Misinformation | Information |

| Bad information | |

| No information | |

| Bad communication | |

| Disagreement with the information received | |

| Incorrect registration in the medical history | |

| Misidentification of the patient. |

A descriptive analysis of the collected variables was conducted to study the claim's characteristics. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for qualitative variables. For the analysis of quantitative variables, mean ± standard deviation was used when they followed a normal distribution, or median and interquartile range when they did not. The normality of variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Exploratory bivariate analyses were carried out to detect potential dependencies between variables such as age, gender, service utilization, and the probability of filing complaints related to perceived treatment by the user. For this purpose, the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted when dichotomous qualitative variables were compared with continuous variables, depending on normality. When comparing qualitative variables, the Chi-Square test or Fisher's exact test was used. A significance level of 5 % was set for the bivariate analyses. In order to study the trend of some of the variables analyzed, data was taken from the claims presented for the same reasons during the years 2020 and 2021.

Ethical and legal aspectsThe present study was evaluated and approved by the Santiago-Lugo Territorial Ethics Committee, with registration code 2023/192.

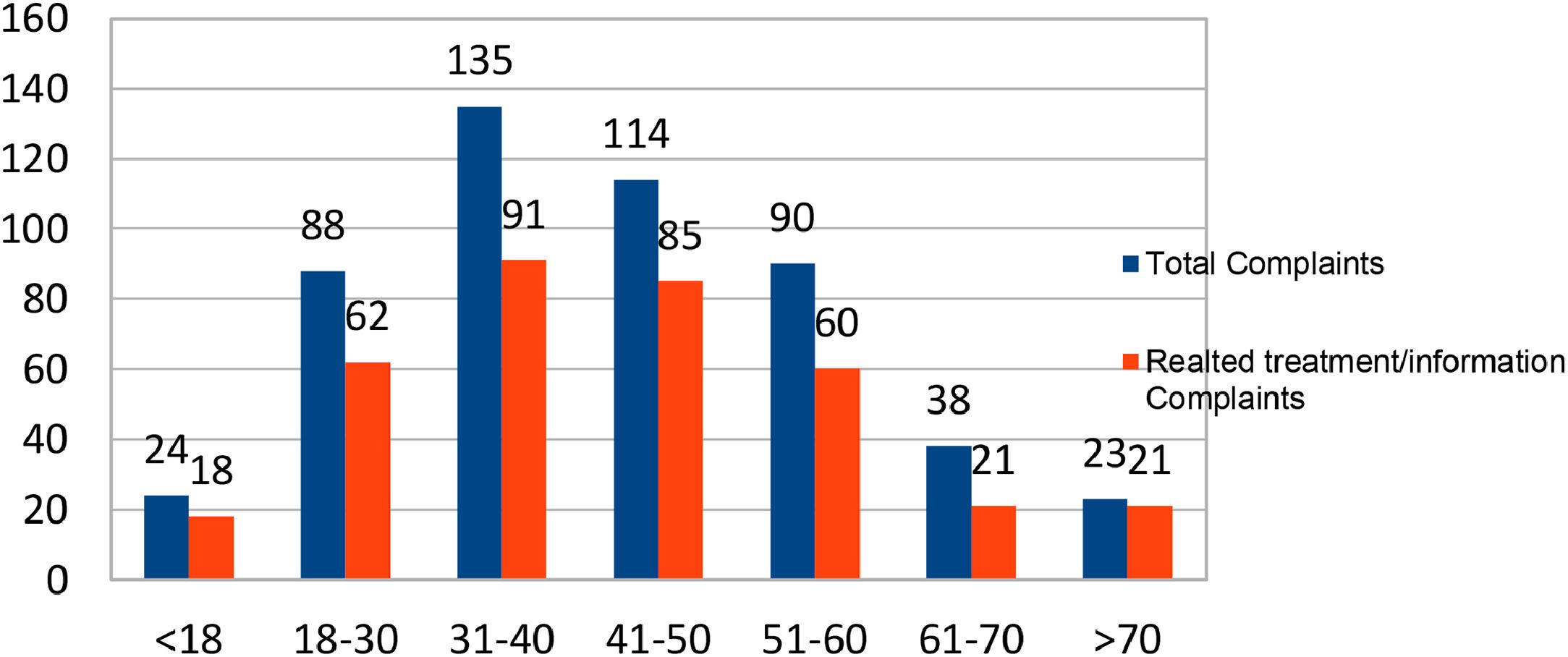

ResultsThe study involved 326 users who submitted a total of 358 claims specifically related to treatment and information. The average age of the participants was 33.5 ± 16.2 years, 64.6 % were ≤ 50 years old. 72.4 % of the sample were women (n = 236, 72.4 %). The authors observe that of the 358 complaints presented for treatment/information, 42 (11.7 %) were presented by people aged 61 or over. 21 (4.9 %) were presented by patients > 70-years old. In comparison, patients ≤ 60 years of age filed 316 claims (88.3 %). The distribution of complaints by age group is seen in Fig. 1.

In 2022, the Cumulative Incidence (CCI) was 55.2 complaints per 100,000 healthcare acts and the Complaint Incidence Rate (CIR), defined as the number of complaints/1000 users/year, was 6.5. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of CCI and CIR during the years 2020‒2022.

The prevalence of complaints related to treatment/information in 2020, 2021, and 2022 was 10.7 %, 13.6 %, and 12.4 %, respectively. The main reasons for complaints were issues related to communication with the patient (79 %), followed by the patient's disagreement with the techniques applied by healthcare staff (17 %), and problems related to a lack of privacy (3 %). The remaining 1 % was related to issues associated with individual/religious beliefs and language.

The distribution of claims for primary care services can be seen in Fig. 3. There were significant differences in the number of complaints filed in urban and rural centers during the year 2022. Rural centers had a median of 7 (IQR11) compared to urban centers, which had a median of 17 (IQR = 10.25), p < 0.01.

Of the total of 358 claims, were 225 against Primary Care physicians (62.8 %), 48 against nurses (13.5 %), Pediatricians 21 (5.9 %), Nurse midwife 8 (2.2 %), Dentist 7 (1.9 %), Pharmacists 1 (0.3 %), Social worker 1 (0.3 %). Dental hygienists and Physiotherapists did not receive any claims in 2022. Non-medical personnel received a total of 47 (13.1 %) claims.

No significant differences based on gender and the number of complaints filed. It was 1.1 ± 0.3 for women versus 1 ± 0.3 for men (p = 0.673). No significant differences were observed regarding gender and the probability of being a hyper-complainer, OR = 1.2; 95 % CI (0.7‒2.0), p = 0.340. The authors conducted a Pearson correlation to determine if there was a relationship between the number of healthcare visits in both primary care and hospital settings in 2022 and the number of complaints filed in the same year. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.14; 95 % CI (0.02‒0.27), p = 0.012.

DiscussionThis study is, to our knowledge, the first one conducted in this setting which analyzes the influence of the number of healthcare visits in a given year on the probability of filing a complaint using the Pearson correlation. It is interesting to note that although the group that visits primary care centers the most consists of older individuals, the majority of complaints were filed by the middle-aged population. This demonstrates that the older population tends to be more accepting of the services provided to them, while the younger population demands greater efficiency and better treatment in healthcare.

Regarding gender distribution, a significant difference emerges between females and males, with women being the ones who file the most complaints. This finding aligns with information gathered from previous studies.20,21 This is likely due to women being more frequent users of primary care centers, either as patients themselves or as accompanying individuals.

On the other hand, it is challenging to compare the most frequent classification of complaint reasons with other studies due to the lack of uniformity in classification. However, in various analyses, the top five most common reasons include choice of doctor or center, dissatisfaction with care, lack of staff, inappropriate treatment, and appointment scheduling.20–23 Communication emerged as the primary issue, accounting for 79 % of the cases, followed by technical aspects at 17 %. In contrast, previous research has highlighted other reasons such as administrative organization, delays in care, and disagreement with institutional norms.24

The authors can observe that significantly more complaints were filed in urban centers than in rural centers. This could be attributed to urban area users having higher levels of education and training, thus being more familiar with the procedures for filing complaints and showing greater initiative in doing so. Additionally, it may also be influenced by the fact that urban populations tend to be younger than rural populations, resulting in a better understanding of web-based platforms and access methods. These findings are consistent with previous evidence.25

Regarding the personnel or service targeted by the complaint, family physicians are the majority, which aligns with findings from other studies,20,21 followed by non-medical staff and nursing personnel. This may be due to the increased contact between family physicians and patients, leading to higher expectations placed on them.

This study highlights that complaints and grievances in general, particularly those related to information, have been increasing in recent years. Increased user demands are related to high healthcare utilization, which influences the likelihood of filing a complaint.26 This increase can also be explained because the web app, which can be used from any platform, has been used since 2019.

To reduce the number of complaints regarding information should improve professional-patient communication, focused on improving strategies against the pressure exerted by the patient, as reflected in previous studies.27

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 represented a strong disruption of health systems. The present results reveal an incidence rate of 3.2–6.5 users/year in 2020 and 2022, respectively. This could be influenced by COVID-19 disruption. However, previous studies conducted in these setting reported incidence rates of 2.4/1000 users/year in 2001, 4.8/1000 users/year in 2005, 3.6/1000 years in 2007, and 5.3/1000 years in 2008.20–22 Although the incidence does not seem to have changed much in the pandemic years with respect to previous evidence, the present results must be evaluated carefully.

A notable strength of this study lies in its utilization of complaint and suggestion data analysis, serving as an indirect yet valuable method for evaluating user satisfaction.20,21,27 Through rigorous and comprehensive scrutiny of these inputs, the authors can effectively identify issues pertaining to the services rendered in the studied centers. Subsequently, this facilitates the implementation of improvements aimed at providing the highest standard of service to our population.

As a limitation, it's important to highlight that this study specifically focuses on complaints related to treatment and information provision. This focus was chosen due to the prevalence of such complaints, as evidenced by similar studies conducted within this setting.21 Additionally, it's crucial to acknowledge that the reliability and accuracy of data provided by primary care users may be influenced by subjective factors.28,29 Furthermore, the classification of complaints depends on the individual criteria of administrative professionals responsible for evaluating and categorizing them. This subjectivity could potentially lead to ambiguity regarding the total number of complaints related to the specific issues analyzed in the present study. To address this, implementing an IT tool capable of categorizing complaints based on inherent keywords, along with establishing standardized protocols for complaint management, could enhance consistency and accuracy in classifying all received complaints.30

Another limitation was the lower number of complaints processed by elderly individuals, which may be due to the digital divide that exists among older people, who have less knowledge of computer applications as well as less knowledge of access to these applications. There is evidence that can explain the present results, since it has been shown that the older they are, the more difficult it is for patients to access technology, such as using mobile phones and health applications.31,32

Another possible limitation was that the present study did not evaluate the influence that the quotas of primary care professionals could have on the probability of receiving any complaint/claim for treatment/information. There is evidence that the higher the patient quotas, the greater the workload of the primary care professional, which implies greater stress for the professional and a greater probability of making errors. This increases the probability of receiving a complaint or claim, including complaints about the treatment received. This is reported in references 20, 21, and 22 of the previously evaluated manuscript. This phenomenon is also an intercultural phenomenon, as evidence shows.33–35

ConclusionsThe implications of this study advocate for the implementation of innovations in continuous training for primary care professionals. This initiative aims to improve the dynamics of the relationship and communication between professionals and patients, resulting in increased levels of patient satisfaction. Strengthening organizational structures and continuity of care processes is equally imperative to foster deeper connections with users. This entails creating additional avenues and channels to facilitate enhanced communication for both patients and users in general.

Ethics concernsThe study was approved by the Territorial Ethics Committee of Santiago-Lugo (protocol code 2023/192).

FundingThis research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies, commercial entities, or non-profit organizations.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMaría F. Velázquez-López: Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. María García-Pérez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Montserrat Souto-Pereira: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Juan M. Vazquez-Lago: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.