Previous studies have demonstrated the role of inflammation in acute heart failure. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio was found to be a useful inflammatory marker for predicting adverse outcomes. We hypothesized that an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio would be associated with increased mortality in acute heart failure patients.

METHODS:The study cohort consisted of 167 acute heart failure patients with an ejection fraction <50%. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality, and the patients were divided into two groups according to in-hospital mortality.

RESULTS:In a multivariate regression analysis, including baseline demographic, clinical, and biochemical covariates, the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio remained an independent predictor of mortality (OR 1.156, 95% CI 1.001 - 1.334, p = 0.048).

CONCLUSION:In conclusion, an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio seems to be a predictor of short-term mortality in patients with acute heart failure and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.

Acute heart failure (AHF) is the term used to describe the rapid onset of or change in symptoms and signs of heart failure (HF) (1). The prevalence of the syndrome is increasing due to the frequency of coronary artery disease and the growing elderly population. In addition, AHF is associated with high mortality and morbidity (2). Therefore, the early identification of patients at high risk of AHF is important. Many prognostic factors have been found to be related to AHF in past studies (3-10). Several of these factors are associated with inflammation. Additionally, there have been studies of inflammation in AHF patients (11-13).

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in the peripheral blood is reported to be an easily assessable factor. An increased neutrophil count might reflect inflammation, and lymphopenia is an indicator of physiologic stress. Data on the ability of the NLR to predict cardiovascular risk in different patient groups have been reported(14-19). However, the relationship between the NLR and in-hospital mortality in AHF patients has not been assessed. We hypothesized that an elevated NLR would be associated with increased mortality in AHF patients.

METHODSFrom January 2010 through October 2012, consecutive patients who were hospitalized at our center because of AHF were recruited. Included patients were required to have the following: progressive dyspnea associated with clinical signs of pulmonary congestion that required hospitalization and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%. Patients with known evidence of acute myocardial ischemia, cardiogenic shock, hematological disease, neoplastic metastases to the bone marrow, sepsis, pregnancy, severe arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, infection, chronic inflammatory conditions, glucocorticoid therapy, a history of glucocorticoid use 3 months before admission, and/or other extracellular fluid-increasing diseases (e.g., hypothyroidism and liver cirrhosis) were excluded. Patient baseline characteristics and in-hospital data were recorded on case report forms. All patients underwent LVEF assessment before or <24 hours after admission. Patients who were admitted from the ER mostly underwent an echocardiogram in the ER before admission. Patients who were admitted from the clinic underwent an echocardiogram in the intensive care unit or ward after admission. The hospital's institutional review board approved the study.

All venous blood samples were obtained upon patient presentation, before administration of drugs. Total white blood cell, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts were obtained on admission using an automated blood cell counter. The NLR was calculated as the ratio of the neutrophil count to the lymphocyte count, both obtained from the same automated blood sample on admission of the study population.

All analyses were performed using SPSS V 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The baseline characteristics of the groups were compared using analysis of variance for continuous variables and the χ2 statistic for categorical variables. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the respective independent effects of several variables on mortality. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for each covariate. For all tests, which were two-sided, a p-value<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

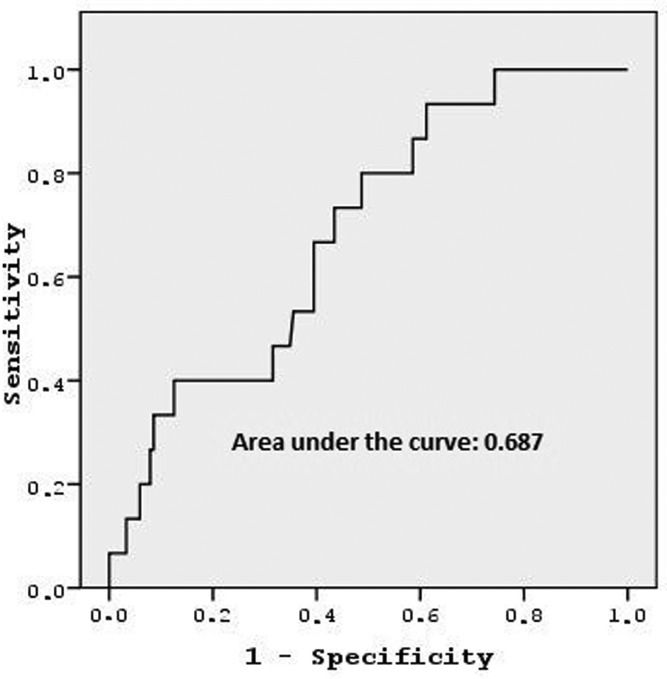

RESULTSA total of 167 consecutive patients were admitted to our institution with AHF during the study duration. Table1 presents the baseline clinical characteristics according to in-hospital mortality. Group 1 consisted of patients who died in the hospital. Group 1 comprised more elderly individuals, and patients in this group more frequently underwent monitoring for atrial fibrillation (AF) on admission. In addition, this group had lower ejection fraction (EF) values compared with those of the other group. Other parameters were similar between the two groups. Figure1 shows that in an ROC curve analysis, the NLR value needed to detect in-hospital mortality with a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity of 60.5% was 4.78. The area under the curve was 0.687.

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15 | 152 | |

| Age | 75±8 | 67±9 | 0.002 |

| Male (%) | 40 | 62.5 | 0.079 |

| Ischemic HF (%) | 52.3 | 61.8 | 0.352 |

| Hypertension (%) | 60 | 57.1 | 0.531 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 53.3 | 50.7 | 0.529 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 60 | 36.2 | 0.065 |

| History of percutaneous intervention (%) | 46.7 | 37.5 | 0.333 |

| History of coronary artery bypass grafting (%) | 20 | 14.5 | 0.396 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 60 | 28.9 | 0.017 |

| NYHA class III or IV | 80 | 73.7 | 0.428 |

| Use of beta-blockers (%) | 33.3 | 40.1 | 0.413 |

| Use of ACEI (%) | 73.3 | 65.6 | 0.384 |

| Use of spironolactone (%) | 26.3 | 33.6 | 0.411 |

| Use of diuretics (%) | 40 | 39.5 | 0.587 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 30±6 | 34±7 | 0.025 |

| Serum hemoglobin levels (g/dl) | 12.5±1.7 | 12.2±1.8 | 0.585 |

| Serum Na levels (mmol/l) | 132±4 | 134±5 | 0.141 |

| Serum creatinine levels (mg/dl) | 1.4±0.8 | 1.2±0.5 | 0.161 |

| Mean NLR | 7.2±4.8 | 4.8±3 | 0.007 |

NYHA: New York Heart Association.

HF: Heart failure.

ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

As shown in Table2, we performed univariate logistic regression including NLR values and other risk factors for mortality. Table3 presents the factors associated with mortality that were analyzed in the multivariate logistic regression model. Age, EF, and the NLR (OR 1.156, 95% CI 1.001 - 1.334, p = 0.048) were found to be independent predictors of in-hospital mortality.

Univariate analysis of risk factors.

| OR | 95.0% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.105 | 1.036-1.1180 | 0.003 |

| Male | 2.500 | 0.846-1.475 | 0.583 |

| Hypertension | 1.121 | 0.380-3.306 | 0.836 |

| DM | 1.113 | 0.384-3.223 | 0.843 |

| Ischemic HF | 0.705 | 0.243-2.047 | 0.521 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.682 | 1.237-10.960 | 0.019 |

| NYHA class III or IV | 1.429 | 0.383-5.325 | 0.387 |

| Use of beta-blockers | 0.746 | 0.243-2.289 | 0.608 |

| Use of ACEI | 1.444 | 0.438-4.760 | 0.546 |

| Use of spironolactone | 0.720 | 0.218-4.760 | 0.590 |

| Use of diuretics | 1.022 | 0.346-3.019 | 0.968 |

| Serum Na levels | 0.918 | 0.817-1.030 | 0.144 |

| Serum creatinine levels | 1.726 | 0.794-3.752 | 0.168 |

| Hemoglobin levels | 1.089 | 0.804-1.475 | 0.583 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.913 | 0.843-0.991 | 0.029 |

| NLR | 1.181 | 1.035-1.347 | 0.013 |

NYHA: New York Heart Association.

HF: Heart failure.

ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

The main finding in this study was that high NLR values were strong predictors of the in-hospital mortality of patients with AHF, independent of other cardiovascular risk factors. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this relationship.

AHF is a very dynamic clinical entity, and its risk is greatest during the first few hours. Therefore, early risk stratification is very important. In this way, early-identified high-risk patients are directed toward more intensive and advanced treatment options. Thus, mortality and morbidity may be reduced.

There are many studies on the association of AHF and inflammation (11,20). Markers of inflammation can provide information about the prognosis of AHF. Lymphocyte and neutrophil counts are markers and may vary depending on the severity of inflammation. Lymphopenia is a common finding during stress responses due to increased levels of corticosteroids and lymphocyte apoptosis (21).

The lymphocyte count is reduced in patients with different cardiovascular disturbances. Bian and colleagues found that a low percentage of lymphocytes could be used as an independent predictor of acute coronary syndrome on admission (22). Studies have shown that a decreased relative percentage of lymphocytes is associated with morbidity and mortality in AHF patients (23,24). In addition, similar studies reported an association with an increased number of neutrophils. Cooper and colleagues reported that the baseline white blood cell count is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with LV dysfunction (25). Both an elevated neutrophil count and a reduced lymphocyte count may be associated with a poor cardiovascular prognosis. Thus, the NLR can be used as a prognostic marker.

There are many studies on the use of the NLR in cardiovascular disease (14,15,17,26). Núñez et al. found that the NLR was a useful marker for predicting subsequent mortality in patients admitted for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (18). Another study found that the NLR is related to no reflow and in-hospital adverse events (14). A similar study on AHF was performed. Uthamalingam and colleagues reported that a higher NLR is associated with an increased risk of long-term mortality in patients admitted with AHF (27). The results of our study are similar. However, we evaluated in-hospital mortality in our study. In addition, the average EF value was lower in our study.

In contrast to other studies, certain parameters known to be associated with mortality (e.g., Na levels, functional status, atrial fibrillation) were not related to prognosis in our study. Similar to other studies, age and EF were related to mortality (7,28,29). However, the mortality rate was slightly higher in our study. The reason for this finding was likely the low rate of using optimal medical therapy (especially beta-blockers). One other reason may be that only patients with systolic heart failure were included in our study.

Our study has certain limitations. First, other inflammatory markers were not analyzed and compared with the NLR. In addition, focusing on cardiac mortality and not including rehospitalizations in the study endpoints could be considered a limitation of this study. Finally, this study represents a small number of patients. Although the blood sampling at presentation was performed before drug administration in all patients, the time of fasting was variable among the patients, which might have had a potential influence on the results. Therefore, a larger prospective study should be performed to emphasize the clinical importance and application of measurements of the NLR in AHF.

In conclusion, an elevated NLR seems to be a predictor of short-term mortality in patients with AHF and a reduced LVEF. The NLR is an easily derived and routinely available measure. Therefore, it might assist in identifying patients at increased risk of mortality.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSTurfan M wrote the manuscript and selected the patients. Erdoğan E, Tasal A, Vatankulu MA, Jafarov P and Sönmez O collected the data. Ertaş G performed the statistical analyses. Bacaksız A performed the literature review. Göktekin O was responsible for the final editing.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.