To determine the utility of pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP) in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients ventilated with low tidal volumes (VT) and to investigate whether a lower ΔRESPPP cut-off value should be used when patients are ventilated with low tidal volumes.

METHOD:This cross-sectional observational study included 37 critically ill patients with acute circulatory failure who required fluid challenge. The patients were sedated and mechanically ventilated with a VT of 6-7 ml/kg ideal body weight, which was monitored with a pulmonary artery catheter and an arterial line. The mechanical ventilation and hemodynamic parameters, including ΔRESPPP, were measured before and after fluid challenge with 1,000 ml crystalloids or 500 ml colloids. Fluid responsiveness was defined as an increase in the cardiac index of at least 15%. ClinicalTrial.gov: NCT01569308.

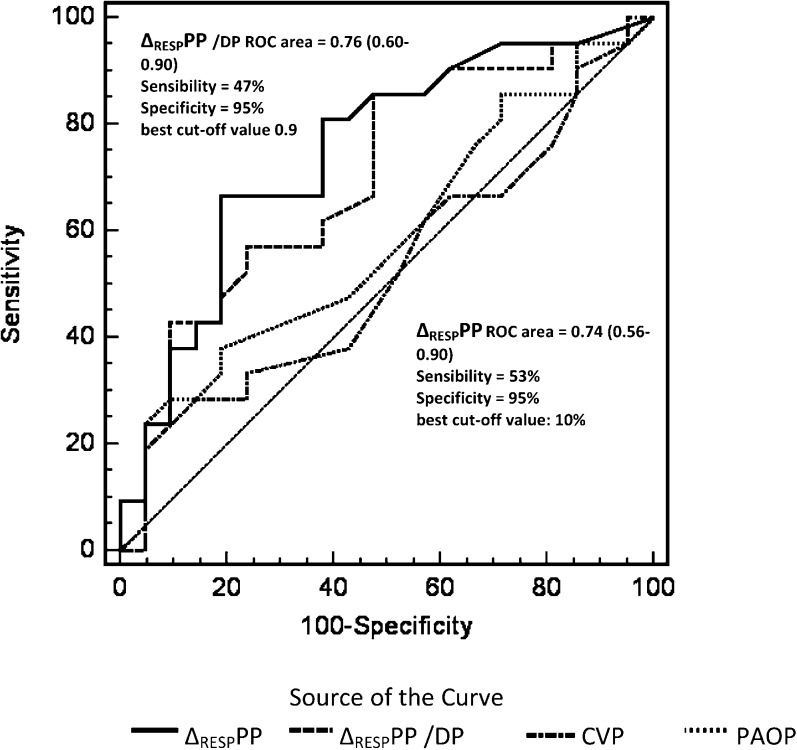

RESULTS:A total of 17 patients were classified as responders. Analysis of the area under the ROC curve (AUC) showed that the optimal cut-off point for ΔRESPPP to predict fluid responsiveness was 10% (AUC = 0.74). Adjustment of the ΔRESPPP to account for driving pressure did not improve the accuracy (AUC = 0.76). A ΔRESPPP≥10% was a better predictor of fluid responsiveness than central venous pressure (AUC = 0.57) or pulmonary wedge pressure (AUC = 051). Of the 37 patients, 25 were in septic shock. The AUC for ΔRESPPP≥10% to predict responsiveness in patients with septic shock was 0.84 (sensitivity, 78%; specificity, 93%).

CONCLUSION:The parameter ΔRESPPP has limited value in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients who are ventilated with low tidal volumes, but a ΔRESPPP>10% is a significant improvement over static parameters. A ΔRESPPP≥10% may be particularly useful for identifying responders in patients with septic shock.

Volume expansion is frequently used to treat critically ill patients with acute circulatory failure. The goal of volume expansion is to increase the left ventricular stroke volume, which consequently increases the cardiac output (1,2) However, only approximately 50% of patients with acute circulatory failure will respond to a fluid challenge (preload-dependent patients) (3). Therefore, the ability to predict fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients is crucial, particularly in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to increased alveolar-capillary membrane permeability (4). Avoiding unnecessary fluid loading has been shown to have a positive effect on patient outcomes (5,6).

Pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP) is one of the most accurate dynamic parameters used at the bedside to identify fluid responsiveness in patients with acute circulatory failure who are undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation (3,7). However, most studies have evaluated patients ventilated with large tidal volumes (≥8 ml/kg). The validity of ΔRESPPP in identifying fluid responsiveness is still under debate when using lower tidal volumes (7–12).

In preload-dependent patients on mechanical ventilation, ΔRESPPP is primarily the result of an inspiratory decrease in the right ventricular (RV) preload secondary to an increase in the pleural pressure, which is affected by the tidal volume (13). Cyclic changes in the stroke volume are due to pleural and intrathoracic pressure variations in this group of patients (8,14). In patients ventilated with low tidal volumes, the variation in lung volume and airway pressure may not be sufficient to significantly change the pleural pressure, venous return or ventricular filling (15,16). Adjusting the ΔRESPPP to account for the driving pressure (DP, the difference between the plateau pressure and positive end expiratory pressures) could be useful in identifying responders with a ΔRESPPP<13% (9). However, the adjustment of ΔRESPPP based on the DP was shown to be as inaccurate as ΔRESPPP alone in patients who were ventilated with a VT<8 ml/kg IBW (8). In lungs with normal compliance values, low tidal volumes induce small variations in the DP, particularly when the DP≤20 cm H2O (9).

The parameter ΔRESPPP may be useful in guiding fluid therapy following lung injuries, but several physiological mechanisms may limit its validity. The current literature regarding the effects of ΔRESPPP during ventilation with low tidal volumes is unclear, and conflicting conclusions have been reported (10,12). The present study was designed to determine the value of ΔRESPPP in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients ventilated with low tidal volumes and investigate whether a lower ΔRESPPP cut-off point should be used when patients are ventilated with low tidal volumes.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThis cross-sectional observational study included patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit at the Hospital das Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA) who required fluid challenge (FC). The study was approved by the HCPA Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was waived because no interventions were performed on the patients.

PatientsA total of 38 patients admitted to the HCPA ICU who received invasive mechanical ventilation between May 2006 and October 2009 were included. The following inclusion criteria were used: i) age≥16 years; ii) hemodynamic instability, defined as the need for norepinephrine infusion and/or intravascular fluid administration to maintain systolic arterial blood pressure >90 mmHg; iii) arterial line in place (radial or femoral); and iv) pulmonary arterial catheter in place. The exclusion criteria were the presence of cardiac arrhythmia, pneumothorax, heart valve disease or intracardiac shunt and previously diagnosed right ventricular insufficiency. The patients were scheduled to undergo FC with colloid or crystalloid solutions as prescribed by the attending physician.

Study ProtocolThe patients were sedated with midazolan and fentanil (scores of -4 to -5 in the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale) (17) and ventilated in a controlled pressure or controlled volume mode (Servo I system v.12 or Servo 900 C, Siemens, Sweden) with a VT<8 ml/kg IBW (51+0.9 [height in cm- 152.9] for men and 45.5 + 0.91 [height in cm- 152.9] for women) (7). The ventilatory and hemodynamic variables were measured before and after FC with the patients in a supine position. Zero pressure was measured at the midaxillary line. The correct position of the pulmonary artery catheter in West's zone 3 was confirmed as described in the literature (18).

Fluid challenge was performed with 1000 ml 0.9% saline solution or lactated Ringer's solution (n = 36) or 500 ml 6% hydroxy-ethyl-starch solution 130/0.4 for 30 minutes (n = 2).

Hemodynamic ParametersVariations in the arterial pulse pressure were visualized on bedside monitors (HP S66 and PHILIPS IntelliVue, MP60, Germany) and measured with the cursor for five breathing cycles. The ΔRESPPP was calculated using the following equation:

where PPmax and PPmin are the maximal pulse pressure at inspiration and expiration, respectively (1).A pulmonary arterial catheter (Edwards Healthcare, Irvine, CA) was used to measure the cardiac output according to the thermal dilution method (three injections of a 10 ml 0.9% saline solution); the systolic, diastolic and mean pulmonary arterial pressures; the pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP, mmHg); the central venous pressure (CVP, mmHg); and the mixed venous saturation (SvO2). The mean arterial pressure (MAP, mmHg), which was measured using the arterial line and heart rate (HR, bpm), was also recorded. All of the measurements were recorded at the end of expiration before and after FC. Patients were defined as fluid responders if the cardiac index increased by at least 15% relative to the baseline.

Ventilation ParametersThe following ventilatory parameters were measured: inspiratory and expiratory tidal volumes, respiratory rate (RR), plateau pressure (Pplat, cmH2O), peak pressure (Ppeak, cmH2O), total positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEPtot), static compliance (Cst) and driving pressure (DP = Pplat-PEEP). All of the measurements were recorded before and after FC.

Statistical AnalysisThe sample size was defined as 38 patients to estimate the correlation between CI and ΔRESPPP 0.5 (moderate to high magnitude), with a level of significance of 0.05 and a power of 90%.

The effects of FC on the hemodynamic parameters were assessed using the paired Student's t-test for normally distributed variables or the nonparametric Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for non-normally distributed variables. The hemodynamic parameters between both groups at baseline and after FC were compared using the two-sample Student's t-test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The results were expressed as the means±SD or the medians (25-75th percentiles).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the ability of ΔRESPPP, ΔRESPPP/DP, CVP and PAOP to predict fluid responsiveness. The optimal cut-off value for the ΔRESPPP ROC curve was determined for the study cohort. The following measures of diagnostic performance were calculated: sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios. Linear correlations were tested using the Spearman rank method. The data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0. A p-value<0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTSOne of the 38 patients was excluded due to cardiorespiratory arrest that occurred during the study. The general characteristics of the 37 patients are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-five of the patients (68%) were in septic shock, and 11 patients were in distributive shock as a result of various causes. None of the patients were in cardiogenic shock.

Patient Characteristics.

| Variables | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Number | 37 |

| Age, years | 54±17 (19-81) |

| Male sex (%) | 20 (54%) |

| APACHE II | 28± 8 (13-51) |

| Septic Shock (%) | 25 (67.5%) |

| Liver Transplantation* (%) | 7 (19%) |

| Acute Pancreatitis (%) | 3 (8%) |

| Cardiogenic Shock (%) | 1 (2.7%) |

| Aortic Surgery* (%) | 1 (2.7%) |

| ARDS (%) | 10 (27%) |

| Crystalloids (%) | 35 (94.5%) |

| Colloids (%) | 2 (5.5%) |

Mean ± standard deviation (minimum and maximum) or percentage.

APACHE II-The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Score II; ARDS- Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

Table 2 shows the baseline hemodynamic and ventilation parameters and data for the responders (17 patients) and nonresponders (20 patients). There were no statistically significant differences between the responders and nonresponders in terms of age (57±16 vs. 53±18 years) or APACHE II scores (28±05 vs. 28±10).

The hemodynamic and ventilatory data of responders and nonresponders.

| Baseline(n = 37) | Responders(n = 17) | Nonresponders(n = 20) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Fluids | Baseline | Fluids | |||

| VT exp ml/kg | 6.5 [6.0-6.5] | 6.5 [6.2-6.5] | 6.5 [6.0-6.5] | 0.75 | ||

| PEEP, cmH2O | 7 6–12 | 8 6–10 | 0.65 | |||

| Ppl, cmH2O | 21.6±6.4 | 20.4±6.0 | 22.6±6.6 | 0.30 | ||

| DP | 12.6±4 | 11.1±3.2 | 12.9±3.8 | 0.15 | ||

| PPV/DP | 0.56±0.56 | 0.83±0.63 | 0.32±0.35 | 0.005 | ||

| Cst, cmH2O | 34±15 | 38±14 | 31±16 | 0.18 | ||

| HR, bpm | 100±25 | 105±28 | 103±22 | 94±21 | 90±19 | |

| RR | 19.9±2.6 | 20.5±2.0 | ||||

| HR/RR | 5.35±1.37 | 5.19±1.08 | 4.6±1.12 | 4.48±1.03 | ||

| MAP, mmHg | 70±12 | 68±9 | 76±11 | 70±14 | 73±17 | |

| MPAP, mmHg | 28±8 | 28±10 | 32±10 | 28±5 | 32±7 | |

| CVP, mmHg | 11±5 | 12±6 | 16±7 | 11±5 | 16±6 | |

| PAOP, mmHg | 14±5 | 13±6 | 18±6 | 14±5 | 18±6 | |

| PPV, % | 6.5±6 | 8.8±6.2# | 5.1±4.6# | 4.4±5.1 | 2.6±3.1 | |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 3±0.9 | 2.9±1.3 | 4.1±2.1 | 3.4±1.3 | 4.1±2.1 | |

| SVI (ml/m2) | 28±12 | 40±16 | 37±14 | 37±15 | ||

| SvO2 (%) | 64.5±14 | 67±15 | 71±8 | 62±13 | 68±11 | |

| Lactate, mEq/L | 4±3.7 | 3.0[1.9-4.0] | 2.0[1.3-4.2] | |||

| Norepinephrine, mcg/kg/min | 0.37±0.52 | 0.4 [0.2-0.6](n = 15) | 0.2 [0.1-0. 6](n = 13) | |||

| Dobutamine, mcg/kg/min | 0.75±1.4 | 2.3±1.6(n = 4) | 3.2±0.9(n = 6) | |||

PEEP: end expiratory pressure; VT exp: expiratory tidal volume; Ppl: plateau pressure; PPV/DP: PPV/driving pressure index; Cst: static complacence; HR: heart rate; MAP: mean arterial pressure; MPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; CVP: central venous pressure; PAOP: pulmonary artery occluded pressure; PPV: pulse pressure variation; CI: cardiac index; SvO2: O2 mixed venous saturation; VP: vasopressor; IN: inotropic.

Analysis of the study cohort revealed that the optimal ΔRESPPP cut-off value for identifying responders was 10%, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) equal to 0.74 (95% CI: 0.56-0.9; sensitivity, 53%; specificity, 95%; PPV, 90%; NPV, 70.4%; and positive and negative likelihood ratios of 9.4 and 0.34, respectively) (Figure 1). After adjusting the ΔRESPPP for DP, similar results were obtained: AUC equal to 0.76; 95% 0.60-0.90; sensitivity, 47%; specificity, 95%; PPV, 89%; NPV, 68%; and positive and negative likelihood ratios of 9.4 and 0.56, respectively. The ΔRESPPP and ΔRESPPP/DP were more accurate than CVP and PAOP for identifying fluid responsiveness (Figure 1).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP), ΔRESPPP adjusted to driving pressure (ΔRESPPP/DP), central venous pressure (ROC area: 0.57 [0.38-0.76]) and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (ROC area 0.51 [0.32-0.70]) to determine patient responses to volume expansion. The area under the curve for ΔRESPPP or ΔRESPPP/DP is greater than that for the central venous pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP). PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; LR +: positive likelihood ratio; LR: negative likelihood ratio.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the ΔRESPPP and cardiac index variation. Of the ten patients with a ΔRESPPP≥10%, nine were true responders. Twenty-seven patients had a ΔRESPPP<10%, but only nineteen were nonresponders. The other eight responders showed cardiac index variations of up to 75%. Of the responders, the ΔRESPPP/DP index was significantly lower in eight patients with a ΔRESPPP <10% compared with nine patients with a ΔRESPPP>10% (0.33±0.24 vs. 1.31±0.5; p<0.05).

Twenty-five patients were in septic shock (15 nonresponders with a ΔRESPPP<10%, one nonresponder with a ΔRESPPP≥10%, seven responders with a ΔRESPPP≥10%, and two responders with a ΔRESPPP<10%). For the 10% cut-off point, the AUC was 0.84, the sensitivity was 77.8%, the specificity was 93.3%, the PPV was 87.5%, and the NPV was 88.2%. The positive and negative likelihood ratios were 0.13 and 0.23, respectively (Figure 3).

DISCUSSIONThe data in the present study support previous studies (7–10), by demonstrating that ΔRESPPP has limitations in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients ventilated with low tidal volumes but is an improvement over conventional static parameters. The primary finding of this study is that although the ΔRESPPP had a low sensitivity, almost half of the responders had a ΔRESPPP <10%. With the exception of one patient, all of the patients with a ΔRESPPP≥10% responded to FC, which indicates that this parameter is a useful variable for evaluating fluid responsiveness.

The mean baseline ΔRESPPP in this study was low (6.5%). There are several explanations for this observation. First, the patients had already been resuscitated. Second, the patients were ventilated with a low VT (6.5 ml/kg). The use of low VTs in patients with normal lung compliance scores or ARDS induces less pronounced changes in blood pressure waveforms because cyclic variations in the pleural pressure are influenced by the magnitude of the tidal volume and, to a lesser extent, DP (1). As in previous studies, this phenomenon explains the lower cut-off value for ΔRESPPP in patients ventilated with reduced tidal volumes, particularly when the DP≤20 cmH2O (9). The mean DP in this study was low (12.6±4), and our attempts to adjust for DP (8) did not increase the accuracy. We observed a greater ΔRESPPP/DP in the subgroup of responders and a ΔRESPPP>10% compared with the patients with a ΔRESPPP<10%. In patients with decreased lung compliance (acute lung injury/ARDS), the impact of the alveolar pressure on pleural pressure is even less pronounced and is not linear. The association between low tidal volumes and low alveolar compliance (high driving pressure) decreases the effect of positive pressure on venous return and myocardial contractility (19). Third, the ΔRESPPP depends on the RR and HR/RR ratios. The ΔRESPPP is insignificant in responders when this ratio is below 3.6, as shown in De Backer et al. (20). Although the mean HR/RR ratio was lower in the nonresponders (p = NS), it was much higher than 3.6.

PEEP induces a decrease in the cardiac output due to the negative effect of increased pleural pressure on right ventricular filling and increased transpulmonary pressure on the right ventricular afterload in a hypovolemic state, which increases the pulse pressure variation (21). However, the pulse pressure variation results from a complex interaction between hemodynamic and ventilatory mechanisms, including VT, PEEP levels, lung volume and lung compliance (8). Cyclic changes in the pleural pressure are mostly determined by the magnitude of VT (13). In this study, the effects of PEEP on ΔRESPPP appeared to be less important because the mean PEEP levels were low (<10 cmH20). PEEP levels were similar between responders and nonresponders.

Pulmonary artery hypertension and/or right ventricular dysfunction may also contribute to false positive cases when identifying responders (22,23). We did not evaluate signs of right ventricular failure, which can compromise the flow response to an FC. However, the mean pulmonary artery pressure was comparable to values observed in other studies in patients with ARDS (10,12).

Predicting fluid responsiveness is particularly important in patients with ARDS. There are few studies that have properly addressed this issue. Two studies reported AUCs similar to the results in this study with different ΔRESPPP values. In 22 patients with ARDS, Huang et al. reported a cut-off point of 11.8% with a low sensitivity (68%), a high specificity (100%), and an AUC of 0.77 (10) using similar methods. Lakhal et al. recently evaluated 65 patients with ARDS after a fluid challenge to determine whether the CI increased by 10% (12) and reported a cut-off point of 5% with a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 85%. The authors criticized Huang et al. interpretation that ΔRESPPP is a reliable predictor of fluid responsiveness because they considered the lower bound of the AUC 95% confident interval to limit accuracy. The lower bound in the present study was only 0.51. Although we agree that the accuracy may be limited, we also agree with Huang et al. in that a high specificity is sufficient to justify the use of ΔRESPPP at the bedside. However, this study is different because we only studied ten patients with ARDS, and six were nonresponders with a ΔRESPPP<10%.

There were no significant differences in the hemodynamic parameters between the groups. It should be noted that 28 of the patients (75%) were being treated with norepinephrine, with similar proportions in both groups. The use of vasopressors does not appear to mask the hemodynamic impacts of mechanical ventilation (23).

In the 25 patients with septic shock, the accuracy of ΔRESPPP to predict fluid responsiveness was even higher than in patients without septic shock. Seven responders (78%) with a ΔRESPPP≥10% were in septic shock, which was similar to the proportion of nonresponders with ΔRESPPP<10% (80%). Although the disease heterogeneity in the group of responders with a ΔRESPPP<10% may partially explain why ΔRESPPP did not indicate an increase in stroke volume, the design of the present study precludes any conclusions regarding the role of physiological changes related to underlying diseases in ΔRESPPP and fluid responsiveness.

As suggested by this and previous studies (7–12), it is not possible to establish a single cut-off point for ΔRESPPP. The interaction between the pleural and intrathoracic pressures and the cardiovascular system is highly complex and has not been completely elucidated. In addition, this interaction involves physiological aspects related to the underlying disease. Low ΔRESPPP in patients ventilated with low tidal volumes is not a contraindication to fluid challenge, although the probability of response is greater when the ΔRESPPP is increased (with the exception of patients with right ventricle insufficiency) (24).

This study has several limitations. We analyzed data from 37 patients instead of 38 as calculated. The heterogeneity of diagnoses precludes the generalization of our findings. Only ten of the patients had ARDS, and their mean plateau pressure was low and static compliance was preserved. Thus, the application of these results to the entire population of patients with ARDS is limited. Although the analysis of the subgroup of patients with septic shock may be an issue, this group of patients was less heterogeneous than the study cohort, and the use of ΔRESPPP might be particularly useful because these patients frequently present with acute lung injuries. Manual measurement of pulse pressure variation using a cursor has been previously employed (1), and there is not sufficient evidence that automatic measurement of pulse pressure variation is advantageous.

In conclusion, pulse pressure variation had limited value as a predictor of fluid responsiveness in patients ventilated with low tidal volumes. The most accurate ΔRESPPP cut-off point to identify fluid responsiveness was ≥10%. Although a universal cut-off point may not be determined, a ΔRESPPP≥10% can assist in identifying fluid responsiveness, particularly in patients with septic shock.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSOliveira-Costa CD was responsible for the project design, data collection and manuscript writing. Friedman G contributed to the project design, statistics, and manuscript writing. Fialkow L and Vieira SR contributed to the project design.

We would like to thank the Fundo de Incentivo a Pesquisa do HCPA (FIPE/HCPA) for financial support.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

![Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP), ΔRESPPP adjusted to driving pressure (ΔRESPPP/DP), central venous pressure (ROC area: 0.57 [0.38-0.76]) and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (ROC area 0.51 [0.32-0.70]) to determine patient responses to volume expansion. The area under the curve for ΔRESPPP or ΔRESPPP/DP is greater than that for the central venous pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP). PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; LR +: positive likelihood ratio; LR: negative likelihood ratio. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing pulse pressure variation (ΔRESPPP), ΔRESPPP adjusted to driving pressure (ΔRESPPP/DP), central venous pressure (ROC area: 0.57 [0.38-0.76]) and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (ROC area 0.51 [0.32-0.70]) to determine patient responses to volume expansion. The area under the curve for ΔRESPPP or ΔRESPPP/DP is greater than that for the central venous pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP). PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; LR +: positive likelihood ratio; LR: negative likelihood ratio.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/18075932/0000006700000007/v1_202212011706/S1807593222017719/v1_202212011706/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)