Since the first laparoscopic adrenalectomy, the technique has evolved and it has become the standard of care for many adrenal diseases, including pheochromocytoma. Two laparoscopic accesses to the adrenal have been developed: transperitoneal and retroperitoneal. Retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy may be recommended for the treatment of pheochromocytoma with the same peri-operative outcomes of the transperitoneal approach because it allows direct access to the adrenal glands without increasing the operative risks. Although technically more demanding than the transperitoneal approach, retroperitoneoscopy can shorten the mean operative time, which is critical for cases with pheochromocytoma where minimizing the potential for intra-operative hemodynamic changes is essential. Blood loss and the convalescence time can be also shortened by this approach. There is no absolute indication for either the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approach; however, the latter procedure may be the best option for patients who have undergone previous abdominal surgery and obese patients. Also, retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy is a good alternative for treating cases with inherited pheochromocytomas, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A, in which the pheochromocytoma is highly prevalent and frequently occurs bilaterally.

Pheochromocytoma (PHEO) is a neuroendocrine tumor that derives from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla(1). It is a challenging disease that can be cured by removing the affected adrenal gland(2). Open adrenalectomy has been the standard of care in this situation(1). Laparoscopic adrenalectomy was first described in 1992 by Gagner et al.(3) using the transperitoneal approach. Since then, the procedure has been continuously developed and has become the gold standard of care(4–6). Laparoscopic adrenalectomy has evolved from the transperitoneal approach to the retroperitoneal approach, and even single-site access and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) have been developed(7–10).

Retroperitoneoscopy was first described in 1969 by Bartel(11) as a diagnostic tool. In the following years, it has evolved to a minimally invasive diagnostic procedure and finally became a useful route for operative procedures by the early 90s(12–15).

Retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy was developed in 1993(16), initially only for small benign lesions and recently for lesions >5 cm and even malignancies(17). This technique gained popularity because it allows direct access to the gland and avoids unexpected lesions to intra-abdominal organs. In some academic centers(18), it has become the surgery of choice for adrenalectomy, although it requires a strict working space and an unusual anatomical recognition compared with transperitoneal access.

Of note, retroperitoneal adrenalectomy may be especially useful for treating cases with inherited PHEO, especially those with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2A) in which PHEO frequently occurs concomitantly with medullary thyroid carcinoma and primary hyperparathyroidism. The prevalence of PHEO with MEN2A is 50% and frequently occurs bilaterally (50–60%), either synchronic or asynchronically(19). Recently, PHEO was reported to be highly prevalent in MEN2A patients harboring the double 634/791 mutation in the RET proto-oncogene(20).

In the present paper, we briefly described the revised retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy technique and the outcomes of adrenal lesions that have been operated on using this approach.

Surgical techniqueAfter confirming the diagnosis of PHEO, the patient needs to be clinically prepared for adrenalectomy in order to avoid the possibility of a dangerous intraoperative adrenal crisis. This preparation usually requires at least 4–6 weeks of using either amlodipine, or preferentially prazosin, a selective α1-antagonist. Initially, 1 mg/day is given at bedtime for 10–15 days. Then, 1 mg of prazosin should be added for 7–10 days until a dose of approximately 10 mg is reached. Prazosin has a short effective lifespan and, thus, should be given two or three times a day. Also, the ingestion of large amounts of liquids (>2.5 L/day) and a salty diet in order to expand the extracellular volume and avoid possible postsurgical hypotension or even hypovolemic shock is recommended(21),(22). β-adrenoceptor antagonists (e.g., propanolol) should be added only 2–3 days before surgery, if necessary (e.g., the occurrence of tachycardia)(1),(2),(23). Usually, computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging has been already performed during the diagnostic phase of PHEO and will be useful for choosing specific surgical techniques. For the success of the surgical procedure, it is crucial to obtain a careful surgical history of all PHEO patients who are candidates for retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy. The reason for this is because a previous retroperitoneal intervention may represent a relative contraindication for this procedure. Conversely, previous upper abdominal surgery can make the procedure more attractive.

Surgery is performed with the patient under general anesthesia, with laryngeal intubation and assisted ventilation. A peripheral arterial line and a central venous catheter are inserted for cardiovascular control in all cases. An orogastric tube is routinely placed for the procedure only. The bladder remains empty by using a Foley catheter (RÜSCH®, Teleflex).

There are two basic positions that the patient should be placed into for a retroperitoneocopic adrenalectomy: the lateral posterior and the prone position(24–28), and the surgeon should choose which position he/she prefers. In the lateral position, the patient is placed in total lateral decubitus with hyperextension of the affected side by elevating the lumbar bridge of the table and straightening the ipsilateral lower extremity in order to increase the space between the 12th costal arch and the iliac crest(18),(28),(29) (Figure 1). In the prone position, the patient is placed in a half-jackknife position, with the hip, joints and knees bent at 75–90° (Figure 2). The aim of this position is to increase the space between the last rib and the iliac crest.

Lateral position. The patient is placed in a hyperextension position. 1 – first incision is made below the last rib to create a retroperitoneal space; 2 – second port, 1 cm above the iliac crest, where the 0° endoscope enters; 3 – working port located 4 cm anterior to trocar number 2.

The first incision is usually made just below or at the tip of the last rib, and the retroperitoneal space is reached by sharp or blunt dissection of the abdominal wall. A retroperitoneal space can be created using the index finger or balloon dissection, and the latter option is more suitable for obese patients. Other ports can be placed under finger guidance or by retroperitoneoscopic direct vision. A Hasson-type trocar or a blunt-tip trocar (BLUNT TIP®, Covidien) with an inflatable balloon can be used during the first incision in order to avoid or minimize gas leakage. The distribution of the laparoscopic ports varies among different institutions, and the endoscopic angle depends on the preference of the surgeon. Care should be taken to avoid the subcostal nerves. CO2 pressure can usually be maintained between 10 and 15 mmHg, although a CO2 pressure of 20–25 mmHg can be safely applied for patients in the prone position(30).

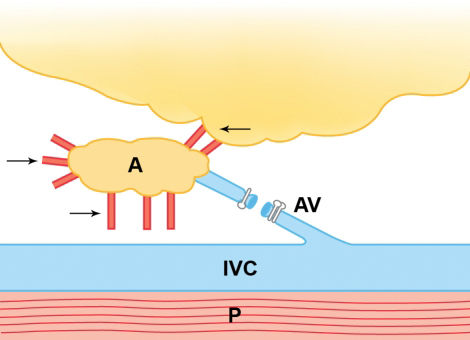

After reaching the retroperitoneum, the surgical tactics involve the identification of psoas muscle for special orientation and either vascular access to the adrenal gland by following the inferior vena cava (on the right side) or the renal vein (on the left side), or posterior access to the adrenal by opening Gerota's fascia, mainly for the prone position. For the right side, the adrenal vein is usually situated posterolaterally to the inferior vena cava (Figure 3); for the left side, the adrenal vein is usually located on the upper surface of the renal vein (Figure 4). In case of PHEO, it is recommended to perform an early ligation of the main adrenal vein in order to minimize potential intraoperative hypertension due to catecholamine release during adrenal manipulation(31–33). Alternatively, some prefer to dissect the gland before adrenal vein ligation(34–36). The inferior and medial aspects of the gland are then dissected, and the small inferior and medial adrenal arteries and veins are separated by clips or sectioned using ultrasonic scissors (Figures 5 and 6). It is important to always avoid direct gland and tumor manipulation during the dissection. The superior aspect of the gland is dissected, followed by the lateral aspects, which are usually poorly vascularized. The specimen is extracted through the first incision using an appropriate retrieval bag system. Placing an aspirative drain for the retroperitoneal space is optional, and the trocars are removed under retroperitoneoscopic observation. The fascia of the port sites that are more than 10 mm are closed, followed by skin closure using an absorbable material.

There are few studies concerning the retroperitoneal approach to treat adrenal PHEO, although most of them are not exclusively related to PHEO cases. Earlier studies were based on case series to show the feasibility and safety of this type of treatment. Also, comparative studies of the transperitoneal and retroperitoneal routes, and between the open and retroperitoneal routes, are available, as commented below.

Clinical seriesLaparoscopy itself has been shown to be a safe procedure and does not increase the cardiovascular risk of treating patients with PHEO(37–39). Some studies do not report any difference between open and laparoscopic approaches in regards to intraoperative hemodynamic changes and complications(37). Nau et al.(38) compared these parameters for the transperitoneal laparoscopic approach to treat PHEO and other adrenal diseases and detected only an increased use of antihypertensive drugs during the procedure for patients with PHEO (p<0.001). They did not find any other increased cardiovascular risk or complication in this group, even when considering the fact that PHEO patients present a significantly higher classification according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (p<0.001). It is important to stress that hypertension must be controlled before the procedure in order to achieve a positive clinical outcome.

Walz et al. described a series of 560 retroperitoneal adrenalectomies that were performed via the posterior approach; 119 of the procedures were for PHEO(30). The mean operative time of all of these cases was 67 min; the operative time for PHEO was significantly longer than for other adrenal diseases (80 vs. 62 min, respectively; p<0.001). There was one conversion to the laparoscopic lateral approach due to severe obesity among the PHEO cases. Overall, intraoperative complications were noticed in 4.2% of cases; severe bleeding that required a transfusion occurred in one patient who was undergoing a partial adrenalectomy. The main complication encountered during follow-up was hypoesthesia or relaxation of the abdominal wall in 8.5% of the 560 cases.

In 2007, Zhang et al.(18) published a series of 824 retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomies that were performed via the lateral retroperitoneal approach, of which 62 of these procedures were for PHEO. In these cases, there was one conversion to open surgery (1.6%) due to large lesions and adhesions. The mean operative time for all of these cases was 45 min. No major bleeding or transfusion was reported.

A prospective study conducted by Walz et al.(39) treated both PHEO and paraganglioma patients. Of 161 treated tumors, 113 (70.2%) were unilateral PHEOs that were treated by retroperitoneoscopy. The median operative time in these cases was 82 min (range: 20–300 min); for the first half of these patients, the median time for the procedure was 110 min, but the second half required only 55 min (p<0.001).

Li et al.(36) described the largest retrospective series specifically for describing lateral retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy that included 131 procedures, including 11 for extra-adrenal PHEO. The authors divided their experiences into three phases and compared their laparoscopic data to open-access cases. In the first phase, laparoscopy accounted for 37% of the cases, and in the third phase laparoscopy was responsible for 83% of the cases. The median operative times in the first, second, and third phases were 105, 85, and 75 min, respectively. Median blood loss in the same phases was 450, 140, and 70 mL, respectively. Fourteen patients (10.7%) had no complications and most of them (71.4%) were considered Clavien grade I complications.

Comparative StudiesA non-randomized retrospective study comparing retroperitoneal access to the open approach for adrenal PHEO(40) reported statistical differences that favored the retroperitoneal access when comparing mean blood loss (140 vs. 592 ml, p<0.05), mean hospital stay (4.4 vs. 9.8 days, p<0.05), and analgesic requirements. The authors concluded that, although technically demanding, retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy is a good option for the treatment of PHEO.

Other studies have compared the transperitoneal and retroperitoneal routes for adrenalectomy, but not specifically for PHEO cases. Baba et al.(41) compared three approaches for reaching the adrenal gland: transperitoneal, lateral retroperitoneal, and lumbar retroperitoneal access. The lumbar approach demonstrated the shortest average operative time: 142 versus 194 min for the lateral retroperitoneal route and 252 min for the transperitoneal route (p<0.02). Of note, the first alternative allows direct access to the gland, with no need to retract other abdominal or retroperitoneal organs. Furthermore, blood loss was significantly lower for both lateral retroperitoneal (22 ml) and lumbar access (32 ml) than transperitoneal access (101 ml) (p<0.01). In 1998, Miyake et al.(42) retrospectively compared these surgical routes of access and verified that operative times were longer and postoperative pain was higher for transperitoneal laparoscopy, although there was no statistical difference. Suzuki et al.(24) compared three different approaches to the adrenal gland: anterior transperitoneal, lateral transperitoneal, and lateral retroperitoneal. They found a mean operative time of 175, 118, and 176 min, respectively. The lateral transperitoneal approach was significantly favored (p<0.0001). No significant difference was found regarding blood loss. Shoulder pain and paralytic ileus occurred in patients of all groups, but in the retroperitoneal approach it occurred only when the peritoneum was opened. Suzuki et al.(24) recommended that experienced surgeons should treat small lesions using the minimally invasive retroperitoneal approach to avoid complications related to peritoneum insufflation.

Other authors did not find any significant differences regarding transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal access. Fernandez-Cruz et al.(43) documented no difference regarding blood loss or hemodynamic parameters between both approaches, in addition to operative time, blood loss and complications. Gockel et al.(33) reported that the median operative time is lower in the transperitoneal approach (85 min) compared with the retroperitoneal approach (120 min) (p<0.001), particularly when the right side was compared. Also, a shorter learning curve was observed for the transperitoneal approach compared with the retroperitoneal approach. These results were explained by earlier recognition of anatomic landmarks during transperitoneal access.

Rubinstein et al.(44) conducted a randomized prospective comparison between transperitoneal and retroperitoneal routes for adrenalectomy. Patients from both groups were comparable with respect to age, body mass index, tumor size, and ASA classification, and no significant differences were noticed. Thus, median operative time, blood loss, and specimen weight were similar in both groups, as well as analgesic requirements, hospital stay, and complication rates. The mean convalescence time was 4.7 weeks for the transperitoneal approach and 2.3 weeks for the retroperitoneal approach (p = 0.02). Two patients in the transperitoneal group developed with port site-related hernias.

A retrospective study comparing the transperitoneal and retroperitoneal approaches for treating PHEO analyzed 99 patients with unilateral adrenal lesions and comparable demographic data(45). There were 40 patients in the transperitoneal group and 59 in the retroperitoneal group. The mean operative time (117 vs. 84 min, respectively; p<0.05), blood loss (340 vs. 200 ml, respectively; p<0.05), hospital stay (7.8 vs. 4.8 days, respectively; p<0.05), and complication rates were significantly higher in the transperitoneal group. Blood pressure fluctuations, long-term blood pressure control, metabolic and imaging follow-up were similar in both groups; however, the recurrence rates were not verified.

Special situationsPrevious abdominal surgery or radiation therapy does not seem to affect the clinical outcome of the retroperitoneal approach. Viterbo et al.(46) compared retroperitoneal access to the kidneys and adrenals in patients with and without previous abdominal surgery but was unable to verify significant differences regarding operative time, blood loss, or convalescence. Retroperitoneal access is the preferred route for patients with a history of prior abdominal surgery as a way for surgeons to avoid visceral and vascular complications (10,28,44,47,48).

Obese patients with PHEO can be preferentially managed with retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy. There are two reported cases that clearly document the feasibility and relative safety of this approach(49),(50). Because of the direct access to the gland, some authors consider obesity as an indication to perform the retroperitoneal approach(28),(44),(51). A high body mass index is correlated with a longer operative time, mainly for those >25 kg/m2(33),(51).

Tumor size must also be taken into consideration when planning the surgical approach. Due to more restricted space, retroperitoneoscopy is usually indicated when adrenal tumors are <7 cm (43),(52), although some experienced centers have operated on larger tumors(18),(30),(53),(54). For both approaches, tumor size >5 cm can increase the operative times(33),(55). When there is suspicion of malignant PHEO, the surgical procedure must be considered. In such cases, the open procedure should be favored over the laparoscopic approach(56), mainly if radiological findings indicate local invasion or, as is the case of large tumors(57), some studies document good outcomes in cases of malignant, organ-confined tumors(52),(57). Also, there is a relative contraindication for retroperitoneoscopy if there has been previous retroperitoneal manipulation or scarring(44). In these cases, the transperitoneal approach would be more suitable.

Laparoscopic adrenalectomy can also be performed on children. Most cases are conducted by the transperitoneal approach. A non-randomized retrospective multicenter study showed that this method is a feasible and secure procedure for young patients, with a 10% conversion rate(58). Furthermore, when referring to the retroperitoneal approach, there are few studies indicating that the surgical positions for adults can also be applied to children. However, there are no available data related to retroperitoneal treatment specifically for PHEO. Most cases are included in non-specific retroperitoneal adrenalectomy series(59),(60), or even included in adult series, indicating the feasibility of the method with no major complications, although right-sided procedures can be technically more demanding(61).

An important issue concerning the retroperitoneoscopic technique is how to teach the procedure to those who do not routinely perform it. A study conducted by Barczynski and Walz(62) reported the experience of a pioneering group in this technique who introduced it to an inexperienced group. The experienced group continuously supervised the student group and offered direct surgical assistance during the initial cases. They compared the first cases of each group and found a significant impact on the operative time and conversions in the learning group. The recommendation was that previous visits and contacts to experienced centers, as well as initial assistance from an experienced surgeon, can flatten the learning curve of the apprentice surgeons, as reflected by safer outcomes for patients. It was estimated that the apprentice had to operate on 20–25 cases under supervision before being able to perform the procedure in under a mean operative time of 90 min.

Retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy can be indicated for the treatment of PHEO with the same peri-operative outcomes as the transperitoneal approach because it allows direct access to the adrenal glands with no increase in the operative risks. Although technically more demanding than the transperitoneal approach, retroperitoneoscopy can shorten the mean operative time, which is useful for cases of PHEO in order to minimize intraoperative hemodynamic changes. Blood loss and convalescence time can be also reduced by this approach. There is no absolute indication for using either the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approaches; however, the latter procedure may be the better option for cases with a previous abdominal surgeries and obese patients.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Hisano M, Vicentini FC, and Srougi M have equal participation in this review article. All three authors worked on technical aspect of the surgery, as well as prepared the illustrations, and reviewed the published literature of the subject.