Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) comprises a heterogeneous group of cancers of the lymphoid system. The incidence of this disease is increasing worldwide. In Brazil, approximately 55,000 new cases are reported each year, and over 26,000 deaths result from NHL annually. In the state of Sao Paulo, the incidence is 12.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.1 B-cell lymphomas are the most common forms of NHL, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype. The International Prognostic Index (IPI) is the primary clinical prognostic index used to classify individuals into different subgroups according to their DLBCL risk.

In the last decade, the overall survival (OS) of DLBCL patients has increased dramatically as a result of the development of cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone (CHOP) therapy. The addition of rituximab, which is a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against CD20, to CHOP therapy results in a treatment paradigm known as R-CHOP. Although R-CHOP is one of the most effective treatments available, approximately 50% of DLBCL patients are refractory to R-CHOP treatment. Rituximab is a humanized IgG1 mAb that specifically binds to CD20, a surface antigen present in the majority of B-NHLs. Although the exact mechanism(s) underlying its anti-tumor activity has not been clearly defined, rituximab has been suggested to act via the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, sensitization to cytotoxic drugs, complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).2 The Fc fragment of rituximab is the major mediator of its therapeutic activity and acts by binding to Fcγ receptors (FcγR) expressed by effector cells.3 Three FcγR classes (I, II, III) and eight subclasses have been described, with different haplotype distributions present in different ethnic groups.4 Polymorphisms in FcγR genes have been associated with anti-tumor efficacy, and this heterogeneous family of receptors is known to play a critical role in immunity by linking humoral responses to cellular responses.3 FcγRIIa (CD32a) and FcγRIIIa (CD16) are known to activate effector cells, whereas FcγRIIb (CD32b) has been shown to inhibit the activation of effector cells.

FCγRIIA, the most widely expressed FcγR, is characterized by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) resulting in either arginine (R) or histidine (H) at position 131 within the membrane-proximal Ig-like domain that determines the receptor's affinity for IgG immune complexes. Consequently, the most striking disparity between the R and H alleles of FcγRIIA-131 is a significant increase in the affinity of the H allele for human IgG2 (and, to a lesser extent, for IgG1 and IgG3).3

Therefore, it is possible that this SNP can influence the anti-tumor abilities of effector cells. However, conflicting results have been reported concerning the role of this FcγRIIA polymorphism. For example, a significant correlation between the FcγRIIA 131 H/H genotype and responses to rituximab has been identified in patients with follicular lymphoma but does not occur in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.5,6 Regarding DLBCL, the FcγRIIA 131 H/H genotype was shown to be predictive for complete remission, but not for overall survival or progression-free survival, in patients with B-cell NHL who had been treated with rituximab and chemotherapy (R-CH).7 However, this study examined a heterogeneous group of patients with different subtypes of NHL, including indolent, aggressive and very aggressive NHL. Other studies have found no significant associations between FcγRIIA polymorphisms and complete remission (CR) rates in DLBCL patients.8 However, the aforementioned studies were performed in Caucasians, and their relevance to individuals of other ethnic backgrounds remains undetermined. Brazilians are one of the most heterogeneous populations in the world, a characteristic that results from five centuries of interethnic crosses between peoples from three continents: Europeans, Africans and Amerindians.9,10 How this large genetic mixture affects the influence of the FcγRIIA-131 polymorphism in the treatment of DLBCL patients is not known. In this study, we investigated the effects of the FcγRIIA-131 polymorphism on the overall survival, disease-free survival and overall response rate to R-CHOP treatment in a cohort of 59 Brazilian patients with DLBCL.

After receiving written informed consent, blood was drawn from 59 previously untreated patients with DLBC. The protocol design was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Patients were treated with 6–8 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (rituximab 375 mg/m2 iv, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 iv, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 iv, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 iv (max 2.0 mg) and prednisone 100 mg/day po days 1–5) every 3–4 weeks. Patients who were seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and those with severe congestive heart failure, kidney failure or liver failure were not included in the study. Patients with bulky disease (i.e., > 7.0 cm) were subjected to radiotherapy (30 Gy) 28 days after the last cycle of chemotherapy. Intrathecal chemotherapy with methotrexate (12 mg) and dexamethasone (2 mg) was administered to patients who exhibited a high risk of central nervous system relapse. The median follow-up time was 19.5 months (range 21.3 to 50.1).

Complete responses to treatment were defined by the complete lack of lymphoma-related signs and symptoms. The criteria for partial responses to treatment (PR) were a 50% (or greater) reduction in lesion size (calculated by finding the sum of the two major measurable perpendicular lengths of the lesions), or the lack of increases in pre-existing lesions, new lesions and B symptoms. Complete mass reductions were considered to be PR when bone marrow infiltration persisted. Responses that failed to meet the criteria for PRs were characterized as refractory, and the development of residual lesions of 25% or more and the appearance of new lesions were considered to be indicative of relapse.11

All of the patients underwent a diagnostic work-up consisting of a tumor biopsy; medical history; biometric tests; a complete blood count; liver and kidney evaluations; serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ß-2 microglobulin measurements; serum protein electrophoresis; serology for HBV, HCV, HIV, HTLV-I/II, syphilis, and South American trypanosomiasis; an electrocardiogram; an echocardiogram; a chest radiography; bilateral BM biopsies; a lumbar puncture; and neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis computer tomography (CT). Patients whose Waldeyer's ring had been involved underwent digestive endoscopies, and those whose facial bones were involved underwent brain and face CTs. Response evaluations were performed after the 4th treatment cycle, the last treatment cycle, every 3 months during the first 2 years after treatment and every 6 months thereafter.

Blood samples were collected in EDTA-containing tubes. DNA was extracted using standard salting out procedures as described elsewhere.12,13 Oligonucleotides for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification were chosen to specifically amplify the FcγRIIA gene and not the highly homologous FcγRIIB and FcγRIIC genes. The following oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA): sense: 5′-GGAAAATCCCAGAAATTCTCGC-3′ and antisense: 5′-CAACAGCCTGACTACCTATTACGCGGG-3′. PCR amplification was performed as described previously.14

Overall survival time was defined as the time period from the beginning of treatment until either the time of death or the time of the last follow-up appointment. The overall response rate was defined as the total percentage of cases exhibiting either complete or partial responses. The disease-free survival period was defined as the time period from the beginning of each positive treatment response until the first observed disease progression, relapse, death, or the last follow-up. Data were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. GraphPad Prism (v5.0) software was used for statistical calculations, and P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

The clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table I. The median age of the patients was 48.6 years. Thirty (50.8%) patients were in Ann Arbor stage III–IV and 29 patients were in stage I–II. Twenty-four (40.7%) patients had more than 3 factors of IPI. Of the patients included in this study, 50 (84.7%) had complete remission, 6 (10.1%) had refractory disease and 7 (11%) relapsed. Six of the study patients (10.1%) died prior to their follow-up(data not shown).

Pretreatment characteristics of patients

| Parameter | Number of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 30.0 | 50.8 |

| Female | 29.0 | 49.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 60 | 44.0 | 74.6 |

| > 60 | 15.0 | 25.4 |

| Clinical Staging | ||

| I/ II | 29.0 | 49.2 |

| III/ IV | 30.0 | 50.8 |

| Performance Status | ||

| 0–2 | 52.0 | 88.2 |

| 3–4 | 7.0 | 11.8 |

| International Prognostic Index | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| 1 | 16.0 | 27.1 |

| 2 | 18.0 | 30.5 |

| ≥ 3 | 24.0 | 40.7 |

| Response | ||

| Complete | 50.0 | 84.7 |

| Refractory | 6.0 | 10.1 |

| Relapsed | 7.0 | 11.0 |

| Polymorphism | ||

| R (HR and RR) | 44.0 | 74.6 |

| HH | 15.0 | 25.4 |

Of the patients in the current study, 15 (25.4%) were homozygous for the H allele, 27 (45.8%) for HR and 17 (28.8%) for RR. Thus, the frequency of H and R alleles in this patient population is consistent with previous reports in the literature.7,8

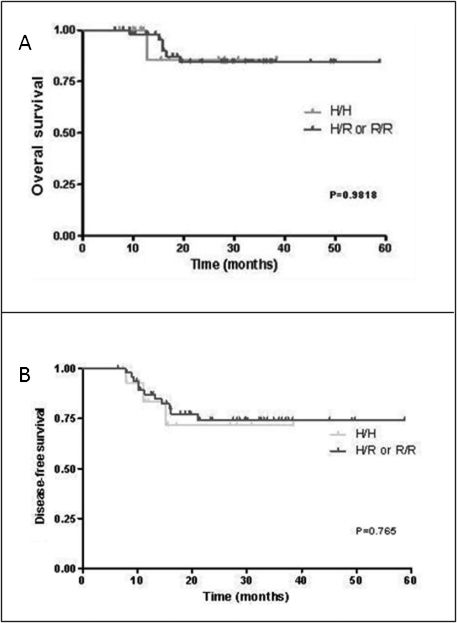

The overall response rate was not affected by the FcγRIIA-131 polymorphism (data not shown). Complete responses were observed in 80% and 89% of patients with HH and HR/RR genotypes, respectively (p = 0.377). Similarly, FcγRIIA polymorphisms were shown to exhibit no significant effects on either disease-free survival or overall survival. Overall, the mean survival time was 23.26 ± 10.42 months for individuals carrying the HH genotype and 12.7 ± 7.42 months for individuals carrying either the HR or the RR genotype (p = 0.98, 95% CI - 0.1194 to 8.801) (Figure 1A). The mean disease-free survival time for individuals with the HH and the HR/RR genotype was 20.96 ± 10.49 months and 12.03 ± 7.71 months, respectively (p = 0.765, 95% CI - 0.2588 to 9.419) (Figure 1B).

Effects of the H/R FcγRIIA-131 polymorphism on 59 DLBCL patients treated with CHOP and rituximab. A. Overall survival, calculated from the beginning of chemotherapy to either the date of death or the date of the last follow-up. B. Disease-free survival, calculated from the beginning of the observed complete or partial treatment response until either the date of first recurrent disease event (relapse, disease progression, treatment failure) or the date of the last follow-up.

The observed level of R-CHOP treatment response in the current study is comparable to those published in the literature. In addition, the lack of an association between the FcγRIIa-131 polymorphism and R-CHOP responses is in agreement with the studies that were previously conducted in primarily Caucasian DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. One potential explanation for these results is that the effects of FcR polymorphisms depend on the genetic background of a given individual. However, it is also possible that the anti-tumor activity of rituximab is independent of this genetic factor and does not depend upon immune effector mechanisms.15

In conclusion, we have shown that the H/R FcγRIIa-131 polymorphism has no impact on treatment outcomes, including the overall response rate, the overall survival time and the disease-free survival time, in a Brazilian population of DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. Therefore, genetic mixture does not seem to affect the influence of the FcγRIIA-131 polymorphism on the treatment responses of these patients.

This work was supported by a grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Proc.573861/2008-0), Brazil, and by the Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia - Fluidos Complexos (INCT-FCx), Brazil.