In the present report, we describe a 3-year-old girl who presented with the full clinical and radiographic features of Larsen syndrome. The knee deformity in our patient was compatible with a complete (grade 3) anterior dislocation of the tibia on the femur. The reduction of knee dislocations in Larsen syndrome patients should be completed before treatment of the hips because 45° of knee flexion or greater is desirable to relax the hamstrings and to maintain the reduction of the hip.

INTRODUCTIONCongenital hyperextension deformities of the knee comprise a spectrum of lesions, including simple hyperextension, subluxation, and complete dislocation. At least half of the babies presenting with these deformities will have some passive flexion at birth that can be managed with casting and/or a Pavlik harness to maintain knee flexion for a few weeks. Fixed subluxation/dislocation is more difficult to treat and often accompanies the fixed dislocation of the hips in the neonate.1–3

In 1950, Larsen et al described multiple congenital large joint dislocations that were associated with facial abnormalities in six genetically-independent patients. The most striking findings were typical flattened “dish-like” faces, bilateral dislocations of multiple joints, and equinovarus deformities of the feet.4 Affected individuals had cylindrical shaped tapering fingers, and a cleft palate and abnormalities in the spinal segmentation were occasionally present. Since that report, numerous other associated clinical and radiographic findings have been determined. Autosomal dominant transmission with clinical heterogeneity is the more common mode of inheritance of this syndrome.4–6 Latta et al identified a juxtacalcaneal accessory bone that may be specific for this syndrome and indicated that congenital knee dislocation is the most difficult deformity to treat.5

Spinal maldevelopment in patients with Larsen syndrome is not an uncommon abnormality and requires prompt measures to prevent cervical spine kyphosis.7,8

In the present work, we report the short-term outcome using serial manipulations and casting followed by an open quadriceps tenotomy for knee dislocation in a child with Larsen syndrome.

CASE REPORTA white newborn female of Austrian descent was delivered by caesarean section at 37 weeks of gestation. As a result of clinical (phenotypic), radiographic, and functional examinations, she was diagnosed with Larsen syndrome at the age of 3 weeks in our department. The family history of the child was non-contributory to this syndrome.

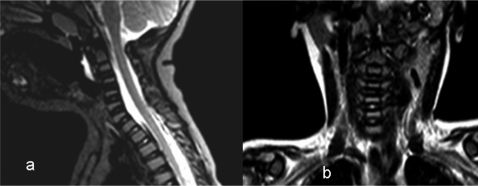

She exhibited the typical facial features associated with Larsen syndrome (i.e., a mid-face hypoplasia with a depressed nasal bridge), bilateral elbow, hip, and knee dislocations, and bilateral talipes equinovarus. Her hips and knees could not be passively manipulated to a normal position, and her elbows had fixed flexion contracture. There were typical hyperextension deformities associated with her dislocated hips and clubfeet (Figure 1). A skeletal survey revealed that bilateral elbow and knee dislocations and a juxtacalcaneal accessory bone were present. The latter finding aids in the diagnosis of Larsen syndrome (Figures 2 A, B, C). Sagittal and coronal MRI imaging of the cervical spine did not reveal associated cervical kyphosis, although mild synchondroses of the vertebral bodies were noted (Figures 3 A, B).

Phenotypic characterization revealed that the child exhibited the typical face associated with Larsen syndrome (a mid-face hypoplasia with a depressed nasal bridge), bilateral elbow, hip, and knee dislocations, and bilateral talipes equinovarus. The child's hips and knees could not be passively manipulated to normal position, and her elbows had fixed flexion contracture. There was a typical hyperextension deformity associated with her dislocated hips and clubfeet.

The functional assessment included the measurement of the degree of passive flexion of the knee joint, palpation of the quadriceps mechanism, and palpation of the relationship between the distal femur and the proximal tibia (the tibia subluxates laterally and proximally on the distal femur as more vigorous flexion is attempted). Contracture of the iliotibial band and patellar instability were elicited.

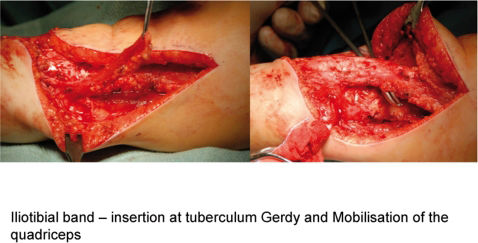

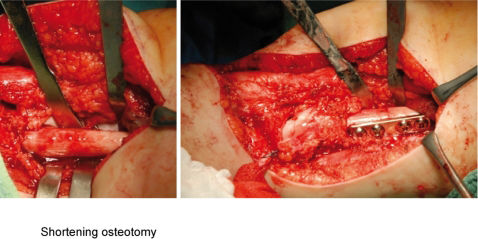

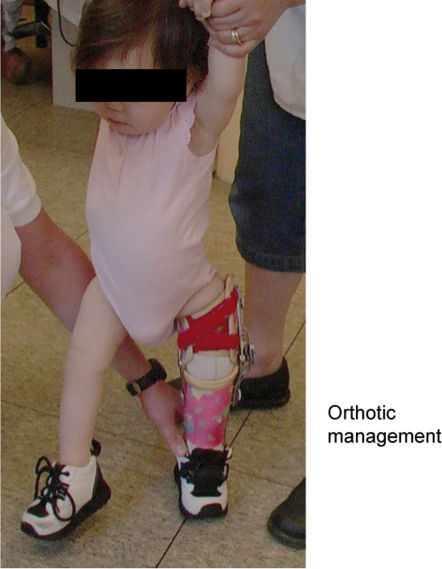

Conservative treatment immediately after birth was performed using gentle manipulations with traction and flexion of the knee followed by a long leg cast fixation until a knee flexion of 90° was achieved. A splint and Pavlik harness were also applied. Forceful manipulation was contraindicated in this patient due to the risk of pressure necrosis of the skin and the separation of the cartilaginous epiphysis. We obtained closed reduction by inducing a neuromuscular blockade of the quadriceps using botulinum toxin (Botox) with percutaneous quadriceps lengthening. This procedure was performed during early infancy using a percutaneous approach with three incisions in the quadriceps. The infant was thereafter mobilized in a spica cast for 6 weeks. There was an acceptable result in the right knee only, and consequently, surgical intervention was planned for the left knee. The essential abnormality that required an operative correction in our patient was the severe shortening of the quadriceps. This operation was performed without a tourniquet, with the patient in the supine position. The incision extended from the lateral parapatellar area, proximal to the crossing of the midline and distal to the patella, and ended at the medial tibial tuberosity. A release of the iliotibial band was performed by maintaining the insertion at the tuberculum Gerdy (Figure 4). An anthrotomy was performed followed by mobilization and lengthening of the quadriceps using a V-Y plasty. The latter procedure was insufficient to reduce the dislocated knee. Thereby, shortening osteotomy of the femur has been applied. At this stage, the joint showed severe instability associated with extensive elongation of the cruciate ligaments. Hence, capsulorraphy, cruciate plasty and anterior stabilization by using Insall method were applied (Figure 5). The postsurgical care included a plaster cast after surgery in a position of 45° flexion. The first change of the plaster was on the second day after surgery, and this change was followed by plaster fixation for 4 weeks. Lastly, splints, physiotherapy, and orthotic management were successfully achieved (Figure 6).

The mutation hot spots in FLNB-gene exons 2-4 and exons 25 to 33 were sequenced. These exons have been describes as having mutations in the literature and encode for functional domains. There were no mutations in these exons in our patient, although the presence of gross deletions or insertions were not assayed with this analysis.

DISCUSSIONCongenital knee dislocation includes three different entities: a) simple hyperextension, b) subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femur, and c) complete dislocation of tibia and femur. The incidence is approximately 2/100,000 live births (60% unilateral and 40% bilateral). Fibrosis and a shortening of the quadriceps are associated with an elongation of the cruciate ligaments, which is always present in this syndrome. The hamstring tendons are displaced anteriorly and are often combined with other orthopedic problems, such as patellar dislocation, hip dislocation, clubfoot, and ligamentous hyperlaxity. There are several types of knee dislocations: type 1, in which the joint can be passively flexed to 45 to 90°, is the most common (50%); type 2, in which the tibia is displaced anteriorly on the femur, albeit with some retained articular contact (45° of hyperextension, passive flexion to neutral position possible), is less common (30%); type 3, which is characterized by a total displacement of the proximal tibia with no contact between articular surfaces, is the least common 20%.1–5,9

Larsen syndrome is a rare inherited defect of connective tissue formation that is transmitted in an autosomal dominant and recessive pattern. First described by Larsen in 1950, its defining features consist of multiple congenital joint dislocations, usually of the hips, knees and elbows, frontal bossing, a depressed nasal bridge, hypertelorism, a flat face, distinctive deformities of the hand and calcaneus, and spinal anomalies, which may lead to major spinal instability and spinal cord injury.7,8

An open reduction of a congenital dislocation of the knee is likely the second most important operative procedure, after cervical spine stabilization. The best results are obtained for this reduction when the knees are reduced by two years of age. Traditional treatment involves the extensive lengthening of the quadriceps mechanism to achieve flexion and an anterior arthrotomy to release the intra- and extra-articular adhesions that prevent congruous knee flexion and to mobilize the patellofemoral joint. However, the common end result of this lengthening is an incomplete quadriceps mechanism, which produces extensor weakness and poor ambulatory function. In addition, if the knee is unstable (particularly the cruciate) or if extensive intra-articular release is required to achieve the reduction, the weakness of the quadriceps further reduces the functioning of the knee and a severe valgus or frank subluxation may result, which makes the patient more dependent on a brace. Notably, the results of arthrotomy and primary femoral shortening to accomplish the reduction and flexion of the knee are more encouraging. The purpose of femoral shortening is to lengthen the quadriceps mechanism without an extensive dissection and lengthening of the muscle-tendon unit itself. With the shortening of the femur, the extension contracture is decompressed, and with a more limited arthrotomy, the intra- and extra-articular obstructions to the reduction of the knee can be released or excised without damage to the suprapatellar quadriceps mechanism itself. The patellofemoral joint can be realigned by extending the arthrotomy proximally on the lateral side of the knee, which frees the patella from its laterally dislocated position and realigns it in its appropriate intercondylar groove, which is aided by femoral shortening.2,9–11

Cervical spine defects, including vertebral body hypoplasia, posterior element dysraphism, and segmentation defects, could result in severe cervical kyphosis or mid-cervical instability with subsequent severe atrophy of the spinal cord, which is consistent with traumatic injury at some cervical levels.7,8,13

Bonaventure et al performed a linkage analysis in three recessive pedigrees from La Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean, which were segregated for a Larsen-like syndrome.16 These authors did not observe a linkage to COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, or COL5A2.

Vujic et al mapped the gene to 3p21.1-14.1 in a large dominant pedigree. This location was close to the COL7A1 locus, but this gene was excluded by linkage.17

The gene, which has now been located, is filamin B.18 This same gene is mutated in atelosteogenesis types I and III and in spondylocarpotarsal syndromes. Mutations cluster in approximately 5 of the 46 exons.

In the cohort of 20 patients reported by Bicknell et al, 6 patients exhibited a 5071G to A mutation.19,20

CONCLUSIONSThe literature suggests that patients with non-syndromic knee dislocations respond well to conservative management of these dislocations with serial casting and or traction and may have a better prognosis than patients with multiple dislocations. Serial casting of the dislocated knee in Larsen syndrome can place the proximal tibial epiphysis and metaphysis at risk for plastic deformation. Difficult syndromic cases, such as those associated with Larsen syndrome, often require open reduction and or arthrotomy and primary femoral shortening to gain reduction and flexion of the knee. Lastly, we wish to stress that patients with Larsen syndrome may present a real challenge for reconstruction.