Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disorder of unknown cause that affects women of reproductive age. The disorder is characterized by the proliferation of atypical smooth muscle cells (LAM cells) around airways, blood vessels, and lymphatics with cystic destruction of the lung.1–3 LAM may occur sporadically or may be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).1

Clinically, patients may develop progressive dyspnea, cough, wheezing, spontaneous pneumothorax, chylothorax, and hemoptysis.3 The diagnosis is confirmed by the identification of diffuse thin-walled lung cysts via thoracic high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) that are associated with a positive tissue biopsy or by the presence of chylothorax, angiomyolipoma, or TSC.1,2 Acute respiratory failure that is secondary to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is an extremely rare manifestation in LAM patients, with only two previous cases described. The mechanism responsible for the comorbid presentation of acute respiratory failure and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, however, is unknown. Nonetheless, it is speculated to be secondary to the obstruction of pulmonary venules by LAM cell proliferation, thereby promoting pulmonary venous hypertension.4,5

In the present work, we describe a patient with a diffuse alveolar hemorrhage that led to acute respiratory failure and death. A diagnosis of LAM and pulmonary arterial disruption caused by LAM cells was confirmed during the autopsy.

CASE DESCRIPTIONA 39-year-old woman of reproductive age presented with progressive dyspnea and was being treated as an asthmatic patient for seven years. A recent spirometry revealed a moderate obstruction that did not respond to bronchodilators. There was no history of cardiovascular comorbidity. In the last month of the patient's life, the dyspnea worsened, and the patient complained of mild hemoptysis, which required hospital admission. A chest examination revealed a respiratory rate of 20/min and diffuse wheezing during expiration without hypoxia.

The patient progressed to acute respiratory failure and rapidly deteriorated with hypoxia. Mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure was necessary. Laboratory studies revealed a decrease in the patient's hemoglobin levels from 10.4 to 6.7 g/dl. The patient's white blood cell count was 12,200/mm3, with normal values for the coagulation parameters. The patient's blood sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, and glucose levels were within normal ranges. The patient's arterial blood gas on 60% oxygen was PO2 68 mmHg, PCO2 45 mmHg, HCO3− 20 mmol/l, a base excess-3,1 mmol/l, and a pH of 7.25. The antinuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor tests were all negative.

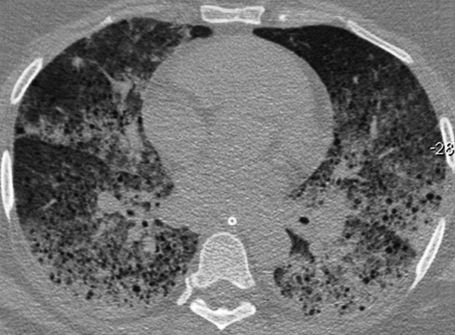

Thoracic computed tomography demonstrated bilateral and diffuse ground-glass attenuation opacities, which were predominant in the lower lobes of the lungs, and thin-walled cysts (Figure 1). A bronchoscopic examination revealed a moderate amount of blood in the segments of both lungs, and the lavage aliquots were progressively more hemorrhagic, which was consistent with the diagnosis of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. The patient developed hemodynamic instability that resulted in the patient's death.

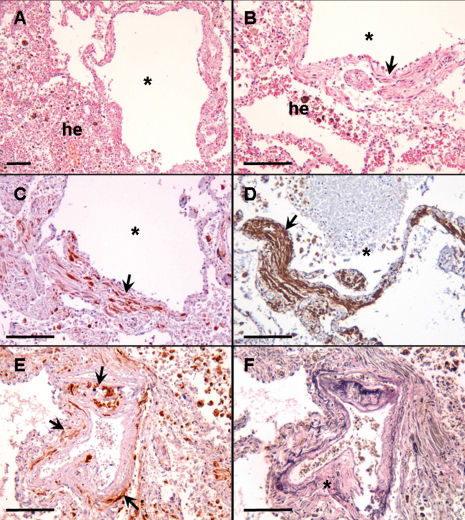

A histological examination during the autopsy revealed cystic lesions in the pulmonary tissue, with alveolar hemorrhaging and atypical smooth muscle cell proliferation at the cyst wall (Figures 2A and 2B). These cells were positive for antibodies against melanoma-associated antigen (HMB-45) and alpha-smooth muscle actin in the immunohistochemical analysis, which is consistent with LAM (Figures 2C and 2D). These HMB-45-positive LAM cells were observed within the small pulmonary artery walls. A disruption of the arterial elastic layer was also observed (Figures 2E and 2F). Hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the adjacent alveolar spaces were also identified (top right in Figures 2E and 2F).

Histological evaluation. Photomicrographs show pulmonary changes observed during the autopsy. A and B) Pulmonary tissue with LAM cysts (*) associated with alveolar hemorrhage (he). Note the smooth muscle tissue proliferation at the cyst wall (B, arrow). HMB-45 and alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive LAM cells at the cysts wall (arrows) are shown in C and D, respectively. E) HMB45-positive LAM cells within the small pulmonary artery wall (arrows). F) Disruption of the arterial elastic layer (*). The adjacent alveolar spaces indicate the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages (top right in E and F). A and B: H&E staining; C, D and E: immunohistochemistry; F: Verhoeff staining. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Due to the rarity of LAM and the non-specific symptoms associated with this disease, it is common for patients with LAM to have a delayed diagnosis or an incorrect diagnosis of diseases such as asthma. When women of childbearing age present with progressive dyspnea and spontaneous pneumothorax, LAM should be considered as a potential diagnosis. The likelihood of LAM increases if the HRCT reveals thin-walled lung cysts and if an obstructive pattern is observed through spirometry. HRCT can reveal abnormalities in the chest radiograph before the identification of LAM, and these abnormalities may vary from a few scattered cysts to cysts that are diffusely distributed. Ground-glass opacities may also be observed in HRCT, and hemorrhaging is a mechanism that may be responsible for these abnormalities. Other common clinical features associated with LAM include the presence of chylothorax and chylous ascites and the worsening of these ascites during pregnancy or after the administration of estrogen.1–3 The pathologic characteristics of LAM include cysts and the multifocal nodular proliferation of immature smooth muscle cells and perivascular epithelioid cells. In immunohistochemical analyses, these muscle cells are positive for HMB-45 and alpha-actin. In addition, the estrogen and/or progesterone receptor can be detected using immunohistochemistry.1

Acute respiratory failure that is secondary to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is a very rare manifestation in LAM patients, with only two case reports to date.4,5 The obstruction of pulmonary venules due to LAM cell proliferation, promoting pulmonary venous hypertension, has been suggested as the underlying mechanism of this manifestation.1,5 The patient in the present case complained of mild hemoptysis and had foci of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the alveoli, both of which were indicative of past hemorrhaging. In the present case, however, we demonstrated pulmonary arterial involvement by LAM cells with the disruption of the arterial elastic layer, which may explain the observed clinical emergency. The presence of venous obstructions or any signs indicative of pulmonary hypertension were not found during the histological examination.

In conclusion, LAM should be included in the differential diagnosis when a woman of reproductive age presents with acute respiratory failure, a significant decrease in hemoglobin, and diffuse ground-glass attenuation opacities. These symptoms are suggestive of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage combined with bilateral thin-walled cysts in thoracic computed tomography.

To our knowledge, the present paper is the first report of an LAM patient presenting with diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage with a histological examination. Contrary to previous speculations, we have shown that pulmonary arterial involvement is likely the primary underlying factor for this severe clinical presentation.