The objective of this study was to evaluate whether the outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter infections treated with ampicillin/sulbactam were associated with the in vitro susceptibility profiles.

METHODSTwenty-two infections were treated with ampicillin/sulbactam. The median treatment duration was 14 days (range: 3-19 days), and the median daily dose was 9 g (range: 1.5-12 g). The median time between Acinetobacter isolation and treatment was 4 days (range: 0-11 days).

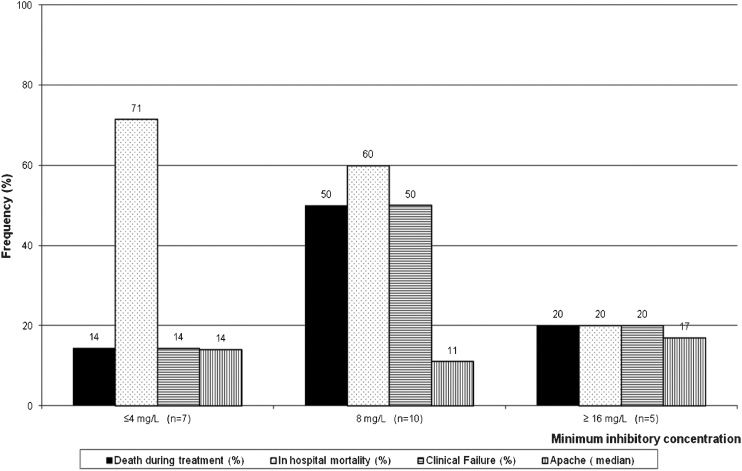

RESULTSThe sulbactam minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) ranged from 2.0 to 32.0 mg/L, and the MIC was not associated with patient outcome, as 4 of 5 (80%) patients with a resistant infection (MIC≥16), 5 of 10 (50%) patients with intermediate isolates (MIC of 8) and only 1 of 7 (14%) patients with susceptible isolates (MIC ≤4) survived hospitalization.

CONCLUSIONThese findings highlight the need to improve the correlation between in vitro susceptibility tests and clinical outcome.

Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. are therapeutically challenging because treatment options are limited. The most studied of these options include polymyxins and sulbactam. Sulbactam, a synthetic beta-lactam, is mainly used as a beta-lactamase inhibitor, but it exhibits in vitro activity against Acinetobacter spp. (1) and has been used to treat infections caused by this organism. In vitro susceptibility testing for sulbactam and Acinetobacter spp. are problematic for multiple reasons. First, the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoint for sulbactam has not been determined. As a result, the criterion for an ampicillin/sulbactam combination is typically used instead (2). Second, unacceptably high proportions of errors associated with the disk diffusion method have been published. In one study, 196 clinical isolates of Acinetobacter spp. were tested using disk diffusion and broth microdilution, and unacceptably high proportions of errors occurred for ampicillin/sulbactam (A/S) (very major: 9.8%; minor: 16.1%) (3) Third, the MIC breakpoints used to interpret results are not well studied and may not predict clinical outcomes.

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether the outcomes of patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter infections treated with A/S were associated with the in vitro susceptibility profiles.

METHODSThis study was conducted at Hospital das Clínicas, a 1,988-bed, tertiary-care teaching hospital affiliated with the University of São Paulo. We performed a retrospective review of all patients who visited the hospital from 2000 through 2004 for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) bacteremia and were treated with at least 4 doses of A/S. Information was collected from the patients' medical records. Infection diagnoses were based on CDC criteria (4) and were obtained from the infection-control database. Patients were excluded if they had received polymyxin simultaneously.

Isolates were phenotypically identified using an automated method (Vitek; bioMerieux; Hazelwood; MO; USA) and confirmed using classical microbiological techniques. The antimicrobial activities of sulbactam were evaluated against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter sp. isolates. Carbapenem resistance was defined as resistance to imipenem by broth microdilution susceptibility testing using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria (MIC≥16 mg/L). Imipenem powder was obtained from Merck & Co., Inc. (EUA).

The sulbactam MIC was determined using the broth microdilution method according to the CLSI guidelines (5). Sulbactam powder was obtained from European Pharmacopoeia Reference Standards CRS & BRP (EDQM European for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare; Council of Europe; Catalogue code Y0000528). The culture medium consisted of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (BBLTM Becton Dickinson). A standardized inoculum was prepared using the direct colony suspension method. Each bacterial suspension was adjusted to the 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (1 to 2 × 108 CFU/mL) using a photometric device (colorimeter Vitek®1, BioMérieux, Etoile, France). The adjusted inoculum suspension was diluted in broth to achieve each an approximate final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in each well. The sulbactam final concentrations were 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 and 128 mg/L. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality control (QC) strains. The MIC results were evaluated by at least 3 observers.

We described the characteristics of the patients, infections, treatments, mortality outcomes during treatment, in-hospital mortality and clinical failure (defined as death or persistent signs and symptoms of infection, persistent isolation of Acinetobacter or a change in the antibiotic between day 3 and 7 of A/S treatment).

Bivariate analysis was performed for 2 outcomes (mortality during treatment and in-hospital mortality). Multivariate analysis using logistic regression was performed for in-hospital mortality. Data were analyzed using EpiInfo 3.5.2 (CDC, Atlanta, GA).

RESULTSSixty-three CRAB infections occurred in 58 patients; of these, 20 received no treatment, 22 received A/S, 10 received colistin, 4 received colistin + A/S, and records were not available for 2 patients. The mean age of the studied patients was 48 years (SD: 23.3). Of the total patients, 64% were male, 21 (96%) used central venous catheters, 16 (73%) used urinary catheters, and 12 (55%) required mechanical ventilation. The median treatment duration was 14 days (range: 3-19 days), and the median daily dose was 9 g (range: 1.5-12 g). The median time between Acinetobacter isolation and treatment was 4 days (range: 0-11 days). Eight patients (36%) received simultaneous carbapenems, and 13 (59%) received vancomycin. A description of the studied cases is shown in Table 1.

Summary of clinical characteristics and outcome of 22 patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. infections treated with ampicillin-sulbactam. Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

| Gender | Age (y) | Apache II score (points) | Underlying diseases | Mechanical ventilation | Urinary catheter | Central venous catheter | Acinetobacter infection | Daily ampicillin-sulbactam dose (g) | Highest creatinine level during treatment (mg/dl) | Treatment duration (days) | Days to initiate treatment | Clinical outcome | In- hospital death | Sulbactam MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 55 | 19 | Renal transplant | No | No | Yes | BSI | 6 | 2.5 | 14 | 9 | Success | No | 2 |

| M | 59 | 9 | Cancer of the larynx | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 3 | 5.3 | 15 | 4 | Success | Yes | 2 |

| M | 84 | 23 | Stroke | Yes | Yes | Yes | Pneumonia | NA | 1.6 | 15 | 7 | Success | Yes | 2 |

| M | 46 | 13 | Burn | Yes | Yes | Yes | Pneumonia | 12 | 0.6 | 14 | 5 | Success | Yes | 4 |

| F | 16 | 14 | Acute abdomen | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 9 | 1.1 | 16 | 4 | Success | No | 4 |

| F | 74 | 15 | Endometrial cancer | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 9 | 2.7 | 14 | 3 | Success | Yes | 4 |

| M | 63 | 13 | Lymphoma | No | Yes | Yes | BSI | 6 | 2,2 | 3 | 3 | Failure | Yes | 4 |

| M | 58 | 22 | Cirrhosis and dialytic renal failure | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 6 | 3.6 | 10 | 4 | Failure | Yes | 8 |

| M | 23 | 18 | Trauma | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 12 | 0.7 | 11 | 6 | Success | No | 8 |

| M | 70 | 19 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 3 | 3.8 | 14 | 2 | Success | Yes | 8 |

| M | 7 | 19 | Burn | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 4 | 0.7 | 9 | 3 | Failure | Yes | 8 |

| M | 24 | 11 | Leukemia | No | No | No | BSI | 12 | 3.3 | 8 | 3 | Failure | Yes | 8 |

| F | 54 | 7 | Breast cancer | No | No | Yes | BSI | 12 | NA | 13 | 36 | Success | No | 8 |

| M | 56 | NA | Acute abdomen | No | No | Yes | BSI | 6 | 4.3 | 11 | 4 | Failure | Yes | 8 |

| F | 36 | 11 | Hemangioblastoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Pneumonia | 12 | 0.6 | 15 | 5 | Sucess | No | 8 |

| M | 60 | 10 | Stomach cancer | No | Yes | Yes | BSI | 12 | NA | 3 | 4 | Success | No | 8 |

| F | 7 | 9 | Heart failure | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 1.5 | 0.9 0.8 | 3 | 3 | Failure | Yes | 8 |

| M | 81 | 15 | Heart failure | No | No | Yes | BSI | 12 | 2.5 | 19 | 0 | Success | No | 16 |

| F | 23 | 18 | Systemic erythematous lupus | Yes | Yes | Yes | BSI | 3 | 4.4 | 16 | 11 | Success | No | 16 |

| F | 33 | 13 | Kidney and pancreas transplant | No | Yes | Yes | Surgical site | 3 | 2.5 | 14 | 5 | Success | No | 16 |

| M | 67 | 22 | Multiple myeloma | No | No | Yes | BSI | 12 | NA | 10 | 1 | Failure | Yes | 16 |

| F | 61 | 17 | Leukemia | No | Yes | Yes | BSI | 9 | 1.6 | 15 | 1 | Success | No | 16 |

M: male, F: female, BSI: blood stream infection, NA: not available; MIC: minimal inhibitory concentration.

The sulbactam MICs ranged from 2.0 to 32.0 mg/L. Five (23%) patients were classified as resistant, 7 (32%) were susceptible, and 10 (45%) were intermediate. Clinical failure occurred in 7 (33%) patients. Seven (33%) patients died during treatment, and 12 patients (55%) died during hospitalization. The outcomes stratified by the sulbactam MICs are depicted in Figure 1. Bivariate analyses showed that male sex and ICU admission were risk factors for in-hospital mortality (Table 2).

Clinical outcome, mortality during treatment, in-hospital mortality and median APACHE II score of patients with infections caused by Acinetobacter spp. stratified by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ampicillin/sulbactam. Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with in-hospital mortality and mortality during treatment in patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. infections treated with ampicillin-sulbactam. Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

| In-hospital mortality | Mortality during treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-survivors (n = 12) | Survivors (n = 10) | RR (95% CI) | p | Death during treatment (n = 7) | Survivors until the end of treatment (n = 15) | RR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 56.3 (21.6) | 44.2 (21) | 0.11 | 48.9 (23.7) | 51.7 (21.6) | 0.97 | ||

| Median (range) | 61 (7-84) | 45 (16-81) | 58 (7-67) | 55 (16-84) | ||||

| Male gender (%) | 10 | 4 | 2.86 (0.82-9.92) | 0.04 | 6 | 8 | 3.42 (0.49-23.6) | 0.15 |

| APACHE II score (points) | 0.44 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.9 (5.3) | 14.2 (4.0) | 16(5.7) | 14.7 (4.4) | ||||

| Median (range) | 15 (9-23) | 14.5 (7-19) | 16 (9-22) | 15 (7-23) | ||||

| Admission to ICU (%) | 10 | 4 | 2.86 (0.82-9.92) | 0.04 | 5 | 9 | 1.43(0.35- 5.74) | 0.61 |

| Acinetobacter infection site (n) | 0.50 | |||||||

| Bloodstream infection | 10 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 0.32 | |||

| Pneumonia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Surgical site infection | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Time between isolation and beginning of treatment (days) | 0.10 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (3.2) | 3.0 (1.0) | 4.8 (2.9) | ||||

| Median (range) | 3 (1-7) | 5 (0-11) | 3 (1-4) | 5 (0-11) | ||||

| Daily Dose (grams) | 6.8 (3.9) | 9.6 (3.7) | 0.21 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (3.9) | 9.0 (3.7) | 0.21 | |||||

| Median (range) | 6 (1.5-12) | 10.5 (3-12) | 6 (1.5-12) | 10.5 (3-12) | ||||

| Simultaneous use of carbapenem(n) | 6 | 2 | 1.75(0.85-3.61) | 0.15 | 3 | 5 | 1.31(0.39-4.44) | 0.66 |

| MIC (mg/L) | 0.19 | 0.24 | ||||||

| ≤ 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| 8 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| ≥16 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | ||||

SD: standard deviation, MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration.

Multivariate analysis revealed that male sex (OR 15.16; 95% CI: 1.15-200.41) and admission to the ICU (OR: 15.20; 95% CI: 1.15-200.40) were associated with in-hospital mortality. The MICs for sulbactam and simultaneous treatment with carbapenems were not associated with patient outcome.

DISCUSSIONSulbactam, a beta-lactamase inhibitor, also exhibits intrinsic activity against Acinetobacter spp., including carbapenem-resistant strains, and therefore represents an alternative to treatment with polymyxins (6). However, the optimal treatment for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infections has not been established (7).

Our case series involved 22 patients with mainly catheter-associated bloodstream infections. Surprisingly, patients infected with Acinetobacter who demonstrated higher MICs were more severely ill but had lower in-hospital mortality rates. Correlating in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility profiles with in vivo clinical outcomes can be difficult. First, appropriate breakpoints should be set. Breakpoints may originally be defined as the concentrations that distinguish subpopulations based on the MIC distribution, although these determinations are also used to guide therapy. Therefore, the use of breakpoints originally created to distinguish microbiological subpopulations to predict clinical success may be problematic. The EUCAST defined the latter breakpoint as a “clinical breakpoint” and the former as a “microbiological or epidemiological breakpoint”. However, this terminology is not universal, and several current guidelines do not make these distinctions (8). To our knowledge, these differences have not been evaluated for A/S, and in our case-series, it appeared that the breakpoints did not adequately predict patient outcomes.

It is always difficult to define the exact cause of death in patients with multi-resistant infections because they often exhibit several underlying diseases, receive invasive procedures and have been hospitalized for long periods (9). In our study, only admission to the ICU and sex were independently associated with in-hospital mortality. Admission to the ICU reflects the severity of the patient's condition, but we cannot explain the influence of gender on mortality.

Clinical efficacy is also influenced by the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of antimicrobials, which may be altered in critically ill patients. A recent study in an ex vivo human model showed that doses of 0.5 and 1 g of sulbactam infused over 30 minutes resulted in bactericidal serum levels at 2 hours after treatment. However, net regrowth and a trend to regrowth occurred, which suggests that a desirable length of time above a MIC>50% would not be achieved with the common dosage regime (1 g every 6 hours) (10).

In addition, in vitro susceptibility tests for sulbactam against Acinetobacter spp. may not be reliable. In one study, 196 clinical isolates of Acinetobacter spp. were tested by disk diffusion and broth microdilution, and unacceptably high proportions of errors occurred for A/S (very major: 9.8%; minor: 16.1%) (3). Another study evaluated the activity of sulbactam-containing combinations by broth microdilution against 469 Acinetobacter isolates and concluded that testing with the inhibitor at a fixed ratio resulted in more reliable results compared to a fixed concentration (11).

Our study was limited by the small number of patients and its retrospective design. To balance these limitations, we used strict diagnostic criteria for infections, included only blood isolates and used mortality as the main endpoint. Unfortunately, we did not have data concerning catheter removal.

In summary, in this cases series, the MIC was not associated with patient outcome, as 4 of 5 (80%) patients with a MIC≥16 μg/mL (considered resistant), 5 of 10 (50%) patients with a MIC of 8 μg/mL (considered intermediate), and 1 of 7 (29%) patients with a MIC≤4 μg/mL (considered susceptible) survived hospitalization. Although we sought to determine alternative sulbactam breakpoints for Acinetobacter infections, this was not possible, which highlights the need for additional studies to improve the correlation between in vitro susceptibility tests and clinical outcome.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSOliveira MS reviewed the medical records, helped writing the manuscript and performed the data analysis. Costa SF performed the data analysis, supervised the experiments and helped writing the manuscript. De Pedri EH performed the experiments. van der Heijden IM performed the experiments and helped writing the manuscript. Levin AS analyzed the data, contributed to the study design and helped writing the manuscript.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.