Poor sleep quality is one of the factors that adversely affects patient quality of life after kidney transplantation, and sleep disorders represent a significant cardiovascular risk factor. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of changes in sleep quality and their outcomes in kidney transplant recipients and analyze the variables affecting sleep quality in the first years after renal transplantation.

METHODS:Kidney transplant recipients were evaluated at two time points after a successful transplantation: between three and six months (Phase 1) and between 12 and 15 months (Phase 2). The following tools were used for assessment: the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; the quality of life questionnaire Short-Form-36; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; the Karnofsky scale; and assessments of social and demographic data. The prevalence of poor sleep was 36.7% in Phase 1 and 38.3% in Phase 2 of the study.

RESULTS:There were no significant differences between patients with and without changes in sleep quality between the two phases. We found no changes in sleep patterns throughout the study. Both the physical and mental health scores worsened from Phase 1 to Phase 2.

CONCLUSION:Sleep quality in kidney transplant recipients did not change during the first year after a successful renal transplantation.

Sleep disorders are more common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) undergoing dialysis (1,2) than in the general population (3). Successful renal transplantation is expected to correct most abnormalities of CKD and significantly improve the patients' health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (4-7), but some studies have demonstrated that sleep disorders do not always improve after transplantation (6-9).

The sleep quality and quality of life of kidney transplant recipients are known to be affected by several factors, such as social-demographic variables, comorbidities, psychiatric disorders, and other physical conditions, including tobacco use, uremia, malnutrition, and anemia (10). Sleep-related disorders have become a focus of interest for research due to increasing evidence of an association between cardiovascular disturbances and sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (11,12). In addition, studies have suggested that sleep disorders are closely linked to physical, psychological and social well-being (13) and cognitive function (14,15).

Detecting the presence of sleep disorders after successful renal transplantation and obtaining a better understanding of this outcome is thus very important due to its impact on patient HRQoL, the perception of changes in lifestyle and well-being and the adherence to treatment.

Therefore, the present study was conducted to prospectively assess sleep quality and HRQoL in kidney transplant recipients at two time points after a successful transplantation. We examined patients during the initial phase (3-6 months post-transplant) and at the second year post-procedure to determine whether there had been changes in sleep quality over time after transplantation. This is a relevant issue because sleep disorders are highly prevalent in patients with chronic kidney disease and are associated with increased cardiovascular risk in addition to having a negative impact on the quality of life of this population.

PATIENTS AND METHODSPatients who received kidney transplants at the Renal Transplantation Service of Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo School of Medicine (HC/FMUSP) from January 1st to December 31st, 2008, were selected to participate in this study.

Eligible patients were individuals 18 years of age or older who had undergone renal transplantation in the past three to six months, had stable renal function with creatinine clearance above 40 mL/min, and who agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form. Patients who were hospitalized within 30 days of inclusion, night-shift workers, patients with active infection, patients who were previously diagnosed with depression, and patients who declined to participate in any phase of the study were excluded.

At inclusion, information was collected about patient age, gender, race, educational background (years of schooling), marital and employment status and medical history. Information on the presence of comorbidities, type of donor, time on dialysis, and laboratory data was retrieved from the patients' hospital files.

All patients were interviewed on two occasions: between the third and the sixth month after transplantation and between the 12th and the 15th month after transplantation. On both occasions, the following variables were assessed: sleep quality using the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); quality of life perception using the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36); the presence of anxiety or depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale; and patient self-care ability using the Karnofsky scale.

Quality of sleepThe PSQI is a self-administered questionnaire that evaluates sleep quality over the past month. It contains 19 questions regarding subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, efficacy, disorders, use of sleep medications, and daily sleep problems. Each component is assessed on a 0 to 3 scale, generating a global score between 0 and 21; higher scores indicate lower sleep quality.

The PSQI identifies two groups of patients: poor sleepers (PSQI>5) and good sleepers (PSQI<5). A global score >5 indicates that the person is a poor sleeper and has severe difficulties in at least two areas or moderate difficulties in more than three areas (16-18). In this study, patients with a score equal to or below 5 were considered as having normal sleep patterns.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)Quality of life was evaluated using the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), which consists of eight sub-scales: physical function, role limitation attributable to physical problems, bodily pain, perception of general health, social function, vitality, role limitation attributable to emotional problems, and mental health. The sub-scales are presented as scores between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating a better health status (19).

Hospital anxiety and depression (HAD)The HAD scale consists of 14 items, of which seven evaluate anxiety (HAD-A) and seven evaluate depression (HAD-D). Each item may be scored from 0 to 3, generating a maximum total score of 21 for each scale. Scores equal to or higher than 9 indicate the presence of symptoms of depression or anxiety (20).

Karnofsky scaleThe Karnofsky scores were used to assess physical health status as follows: 100–normal; 90-minor signs or symptoms of disease; 80-normal activity with effort; 70–unable to carry out normal activity; 60-requires occasional assistance; 50–requires considerable assistance; 40-disabled; 30-severely disabled; 20-hospital admission necessary; 10-moribund. Patients were considered as “rehabilitated” when the Karnofsky score was 70 to 100, “able to care for personal needs” when the score was 60, “requiring considerable assistance” when the score was 30 to 50, and “requiring hospital admission” when the score was 10 to 20 (21).

StatisticsThe Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify data normality. Student's t test was used to compare group averages. Whenever the data normality assumption was rejected, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used. To compare group behavior at each timepoint, we used the paired t test for normally distributed data and the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for non-normally distributed data. The non-parametric McNemar test was used to compare the classification data between Phase 1 and Phase 2.

EthicsThis study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee. Before inclusion, patients received detailed verbal and written information about the study objectives and procedures and signed the informed consent form.

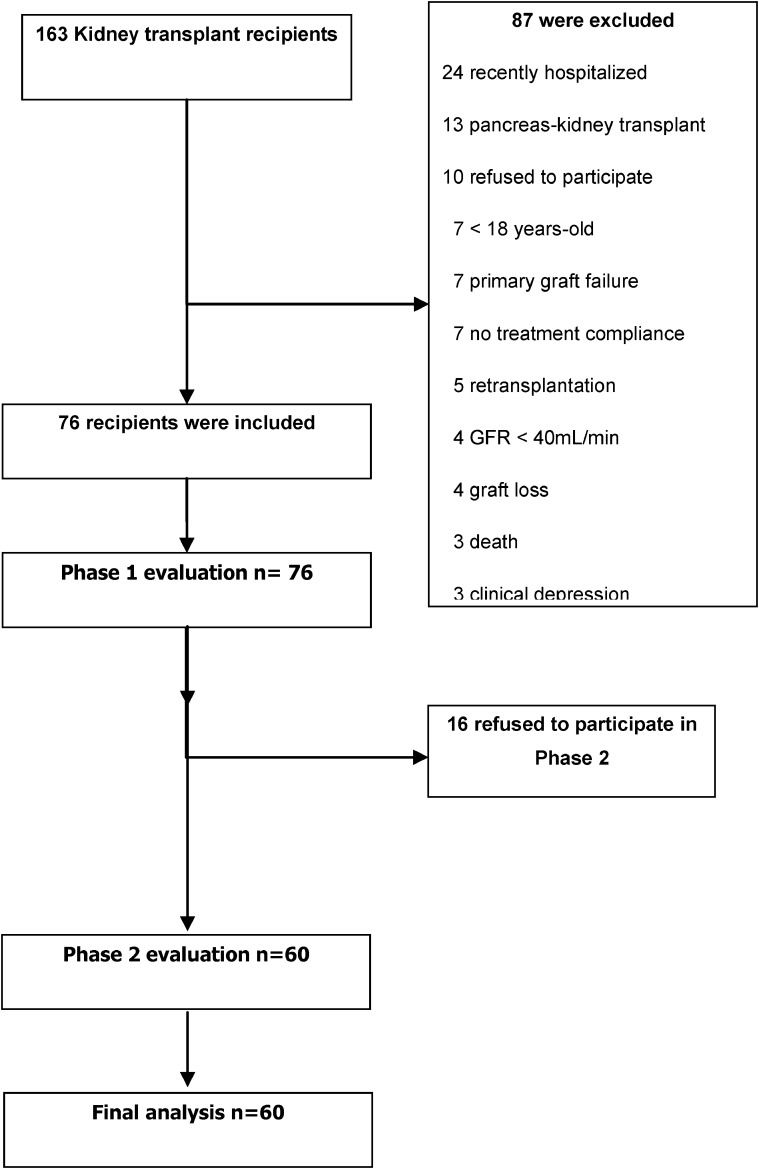

RESULTSIn 2008, 163 renal transplantation procedures were performed at the HCFMUSP, 156 of which were successful. Seventy-six patients met the study inclusion criteria and were included. The details of the inclusion process are shown on Figure 1.

The study population was 60% white, with a mean age of 42±12 years and similar proportions of male and female subjects. Recipients of transplants from living donors represented 59% of the population; the most frequently used immunosuppressive regimen was the triple combination of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Table 1 shows a detailed profile of the study sample.

Patient characteristics.

| Male – n (%) | 31 (51.7) |

| Age (years) (mean/SD) | 42/12 |

| White | 36 (60.0) |

| Years of education - n (%) | |

| <8 | 32 (52.4) |

| 8-12 | 20 (33.3) |

| Undergraduate/graduate degree | 8 (13.3) |

| Non-smoking – n (%) | 57 (95.0) |

| Marital status – n (%) | |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 27 (45.0) |

| Married | 33 (55.0) |

| Immunosuppressive regimen – n (%) | |

| Tacrolimus | 57 (95.0) |

| Prednisone | 60 (100.0) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 49 (81.7) |

| Comorbidity- n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 33 (55.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (18.3) |

| Donor – n (%) | |

| Living | 35 (58.3) |

| Deceased | 25 (41.7) |

Renal function and hematological parameters remained stable throughout the study period, but a significant increase in body mass index (BMI) was observed between the two assessments (Table 2).

Clinical and laboratory data, sleep quality and HRQoL in each study phase.

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-6m Tx | 12-15m Tx | |||

| MeaniSD | MeaniSD | p | ||

| n = 60 | n = 60 | |||

| Serum creatinine(mg/dl) | 1.3±0.3 | 1.3±0.4 | 0.783∗ | |

| Hematocrit | 42.0±6.8 | 41.7±4.9 | 0.546∗ | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 13.5±2.3 | 13.5±1.7 | 0.929∗ | |

| BMI | 25.5±5.3 | 26.4±5.8 | < 0.001∗ | |

| Physical functioning | 88±11.6 | 87±16.6 | 0.723∗∗ | |

| Role physical | 73.3±33.4 | 79.5±12.6 | 0.172∗∗ | |

| Bodily pain | 74.1±16.5 | 71.3±23.9 | 0.422∗∗ | |

| General health | 47.8±17.6 | 46.3±16.8 | 0.363∗∗ | |

| Vitality | 76±16.7 | 70.9±19.3 | 0015∗∗ | |

| Social functioning | 76±28.1 | 68.2±32.3 | 0.156∗∗ | |

| Role emotional | 67.2±36.5 | 54.4±37.3 | 0.015∗∗ | |

| Mental health | 72.8±20.6 | 71.2±18 | 0.610∗∗ | |

| Depression (HAD) | 3.1±3.4 | 3.6±3.6 | 0.432∗∗ | |

| Anxiety (HAD) | 4.9±3.2 | 5.8±3.7 | 0.113∗∗ | |

| Karnofsky | 92.5±8.9 | 93.5±8.2 | 0.326∗∗ | |

| PSQI | 5.4±4.0 | 5.8±3.9 | 0.319∗∗ | |

(∗) paired t test; (∗∗) Wilcoxon non-parametric testBMI, body mass index; HAD, hospital anxiety and depression; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; SF36 –domains.

There was a significant increase in the proportion of patients who were able to work, from 13 (21.7%) in Phase 1 to 28 (46.7%) in Phase 2 (p = 0.006).

Sleep quality and health-related quality of life outcomes after renal transplantationWe observed poor sleep quality in 22 (36.7%) and 23 (38.3%) patients in Phases 1 and 2 of the study, respectively. The mean PSQI showed no significant change from Phase 1 to Phase 2 (5.4 vs. 5.8; p = 0.319).

Most SF-36 domains also failed to show significant differences between Phase 1 and 2. However, the vitality (p = 0.015) and role emotional (p = 0.015) domains showed significant differences at follow-up (Figure 2).

The presence of anxiety and/or depression symptoms and self-care ability, as measured on the Karnofsky scale, were not significantly different at the two time points, as shown in Table 2.

When questioned about their perceived health improvements from the previous year, 93.3% and 85% of the patients reported improvements in Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the study, respectively.

Influence of sleep quality on health-related quality of life and self-care ability after renal transplantationWhen we categorized the patients as poor sleepers (PSQI>5) or good sleepers (PSQI<5) according to the PSQI, we found no significant difference between these groups with respect to demographics, clinical and laboratory data, or renal transplantation parameters (Table 3). However, we found that the body mass index was higher in the poor sleepers group, in which 17.4% of the patients required sleep medication (Table 3).

Clinical and social characteristics versus sleep quality.

| PSQI | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 5 (n = 37) | > 5(n = 23) | |||

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD | 40.08±11.86 | 46.00±11.66 | 0.064(1) |

| Gender | Female | 16 (43.2%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.317(2) |

| Male | 21 (56.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 15 (40.5%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.914(2) |

| Other | 22 (59.5%) | 14 (60.9%) | ||

| Lives with | Yes | 21 (56.8%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.729(2) |

| partner | No | 16 (43.2%) | 11 (42.8%) | |

| Employment status | 11 (29.7%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.105(3) | |

| Smoker | 1 (2.7%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.552(3) | |

| Medication | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.018(3) | |

| Diurnal somnolence | 18 (48.7%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.210(2) | |

| Donor | Living | 24 (65%) | 11 (45.%) | |

| Deceased | 13 (35.1%) | 12 (52.1%) | 0.462(3) | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.32±0.37 | 1.41±0.36 | 0.322(1) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 13.5±2.8 | 13.5±1.4 | 0.899(1) | |

| Hematocrit | 42.1±8.1 | 41.8±4.1 | 0.856(1) | |

| BMI | 24.42±4.66 | 27.30±5.98 | 0.041(1) | |

| Diabetes | 5 (13.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 0.306(3) | |

| Hypertension | 18 (48.7%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.210(2) | |

| Dialysis (months) | 27.38±27.85 | 38.91±39.23 | 0.220(4) | |

(1) Student’s t test; (2) chi-square test; (3) Fisher’s exact test; (4) Mann-Whitney non-parametric test. Data are presented as mean±SD or n (%) as appropriate.

The poor sleepers group showed worse role physical (p = 0.034), social functioning (p = 0.040), and Karnofsky index (p = 0.031) scores, even in the early post-transplantation period. A more frequent use of benzodiazepines and anti-anxiety medication and higher BMI values were observed in the poor sleepers group (Table 4). We also found an inverse correlation between BMI and Karnofsky score; among poor sleepers, patients with higher body mass index values had lower Karnofsky index values. During Phase 1 of the study, labor activity was a significant driver of good sleep quality (p = 0.018). The use of benzodiazepines or anti-anxiety medication was associated with worse SQ in both phases (p<0.001). We found no correlation between napping or smoking and SQ.

Relationship between HRQoL and sleep quality after renal transplantation.

| PSQI < 5 | PSQI > 5 | p∗) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 90.1±10.6 | 84.7±12.7 | 0.053 |

| Bodily pain | 76.2±16.3 | 70.7±16.6 | 0.147 |

| Vitality | 77.5±16.4 | 73.4±17.4 | 0.350 |

| Role emotional | 71.1±37.8 | 60.8±34.3 | 0.173 |

| Role physical | 80.4±30.1 | 61.9±36.0 | 0.034 |

| General health | 45.6±17.5 | 51.4±17.5 | 0.476 |

| Social functioning | 82.0±24.5 | 66.3±31.1 | 0.040 |

| Mental health | 74.9±19.2 | 69.3±22.7 | 0.340 |

| Depression (HAD) | 2.8±3.1 | 3.4±3.6 | 0.513 |

| Anxiety (HAD) | 4.7±3.1 | 5.1±3.3 | 0.591 |

| Karnofsky | 94.3±8.6 | 89.5±8.7 | 0.031 |

There have been a number of cross-sectional studies on sleep quality and sleep disorders (2,6,7,9,10), but none have assessed sleep quality longitudinally after transplantation. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to conduct a sequential assessment of sleep quality in kidney transplant recipients, including the late post-transplantation phase.

Our findings showed no significant change in sleep quality from the early postoperative period to one year after transplantation. We found a high prevalence of poor sleepers [PSQI>5] at the first time point, and the prevalence remained unchanged in the second assessment. We found no difference in the mean PSQI between the two assessments.

This study only included patients with adequate graft function and excluded patients with a current diagnosis of depression or recent hospitalization because those factors might have had a negative influence on patient sleep quality and quality of life and thus increase the heterogeneity of the sample. Therefore, we conclude that despite a successful transplantation, sleep quality did not improve over the study period.

We found no time-dependent change in most quality of life parameters between the two assessments. However, there was a significant difference in the vitality and role emotional scores, suggesting a worsening of these domains over time. Previous cross-sectional studies on sleep quality and quality of life found low scores for these domains in transplant recipients compared with other CKD patients and controls (9,10,22,24). When we compared good sleepers (PSQI<5) and poor sleepers (PSQI>5), we found that the poor sleepers had lower scores in the SF-36 domains, particularly the role physical and social function domains.

We found that 10% of patients exhibited depressive symptoms in each phase, while anxiety symptoms were observed in 10% of patients in Phase 1 and 15% of patients in Phase 2. These values are lower than those found in other studies, i.e., 22 to 39% (32) for depressive symptoms and 10 to 22% for clinical depression (31). This difference may be explained by our exclusion of patients with clinical depression at baseline and/or by our use of a symptom screening tool (HAD). Our study was not designed to diagnose anxiety or depression, but because we used a screening tool, it could be expected that these symptoms would be reported by some patients. The association of anxiety and depression symptoms with poor sleep quality in kidney transplant recipients has been reported previously (30-33), but our study failed to show such an association.

Some reports consider biological and clinical factors to be significant predictors of the SF-36 physical component score, even though these factors can only explain part of the observed changes (5,33,34). However, no correlation has been identified between these variables and the mental health component of the SF-36. Based on these findings, researchers have suggested that comparisons should consider patient age because this variable affects perceived quality of life. To date, no studies have assessed additional personal, environmental and/or clinical factors that might influence the patient perception of quality of life after renal transplantation.

In our study, we also analyzed the correlation between BMI and sleep quality. Sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea, are expected to be associated with high BMI and neck circumference (12). Although our study was designed to assess sleep quality in general and not sleep disorders, we found a correlation between body mass index and sleep deprivation.

Perceived self-care ability was measured on the Karnofsky scale, and we found a negative correlation between poor sleep quality and Karnofsky score. Previous studies support these findings, showing improvements in the Karnofsky and Disease Impact scores after transplantation (35,36). We could therefore assume that the degree of independence, as measured by the patient's self-care ability, may be important for sleep quality.

In our study, patients who were employed reported significantly better sleep quality early after transplantation compared to the patients who did not work. This result suggests that working may be important to achieving good sleep quality, although it should be noted that only a few patients were actively working at that time. Some authors believe that occupation and social reintegration are directly linked to good sleep quality and quality of life (4,5,33,37). Their studies support our findings that having an occupation may be associated with good sleep quality in kidney transplant recipients.

Due to the logistic limitations of including recipients of deceased donor transplants, our study did not assess patients prior to transplantation; therefore, we cannot compare the pre-transplantation period with the other two time points.

One relevant contribution of our study was to show that the prevalence of poor sleep quality remains high after successful renal transplantation and that clinicians should pay attention to subjective factors associated with sleep quality and quality of life even after the first year post-transplantation. The assessment of sleep quality in routine post-transplantation follow-up might contribute significantly to the identification and treatment of these disorders. Additionally, social reintegration and a return to professional activities seem to contribute to improved sleep quality in the first year after renal transplantation.

Determining the influence of the transplantation team on late post-procedural psychological, emotional, and social aspects may help to improve adherence to therapy and patient perception of sleep quality and quality of life. Further studies should address possible interventions, such as identifying patients at risk of emotional and psychosocial conflicts, that might influence treatment outcomes and sleep quality while maintaining the focus on the multidisciplinary approach of renal transplantation.

The study was funded by CAPES.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Silva DS was responsible for the study design and execution. Andrade ESP translated and reviewed the manuscript. Elias RM, David-Neto E, Nahas WC, and Castro MC, reviewed the manuscript. Castro MC designed the study.