Intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) is the third leading non-obstetric indirect cause of maternal death. We describe the anaesthetic management of a 32-year-old woman at 22 weeks gestation with intracranial haemorrhage due to a ruptured arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Managing these patients requires a complex approach with a highly individualised plan involving neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, anaesthetists, obstetricians and neonatologists to assess the risk and benefit of all the different therapeutic alternatives. Given the high risk of further bleeding during pregnancy and the location of the AVM, the best therapeutic option in this case was considered to be a craniotomy and complete removal of the lesion.

La hemorragia intracraneana (HIC) es la tercera causa indirecta no obstétrica de muerte materna. Describimos el manejo anestésico de una mujer de 32 años con 22 semanas de gestación, quien presentó hemorragia intracraneana debida a la ruptura de una malformación arteriovenosa (MAV). Para el manejo de esta clase de pacientes se requiere un enfoque complejo con un plan altamente individualizado en el que participen neurocirujanos, neurorradiólogos, anestesiólogos, obstetras y neonatólogos a fin de evaluar los riesgos y los beneficios de las diferentes alternativas terapéuticas. Considerando el riesgo elevado de sangrado ulterior durante el embarazo y la localización de la MAV, se consideró que la mejor alternativa terapéutica en este caso era la craneotomía para extirpar por completo la lesión.

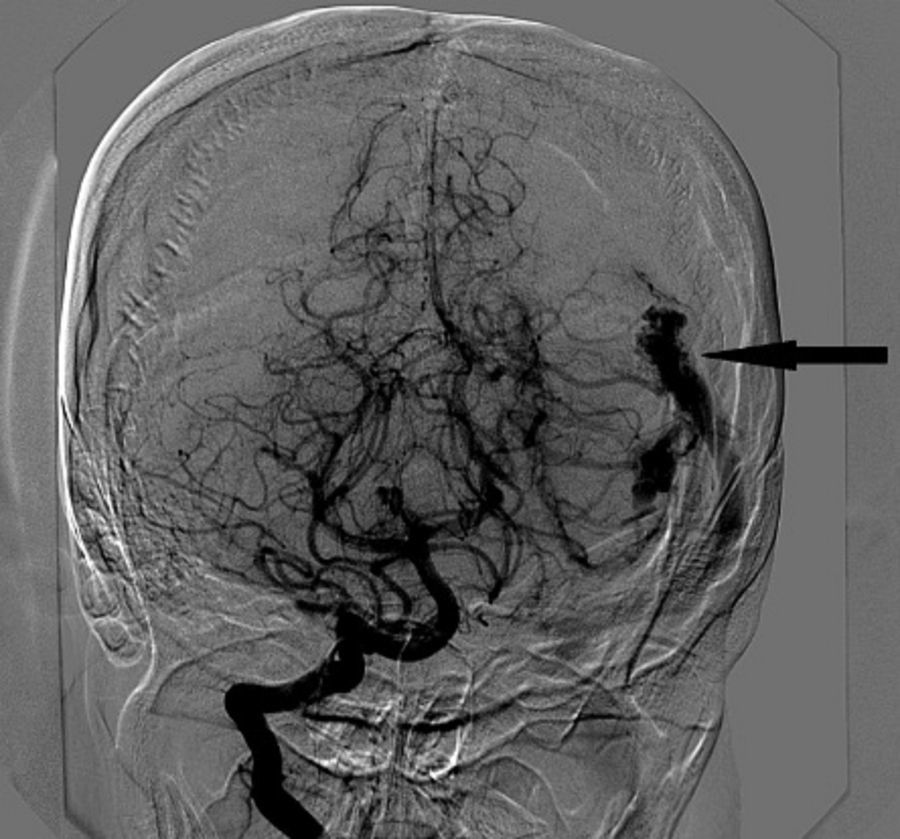

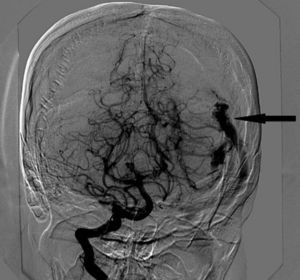

We report the anaesthetic management of a 32-year-old woman at 22 weeks gestation with intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) due to a ruptured arteriovenous malformation (AVM) (Fig. 1). A multidisciplinary medical team decided to perform a craniotomy for surgical resection of the AVM under general anaesthesia.

Case reportA 32-year-old woman with a body weight of 54kg, P1D0, at 22 weeks gestation with no past medical history was admitted to hospital with severe headache associated with nausea and vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 14, motor aphasia, disorientation and a sudden right hemianopia. Abdominal ultrasound showed a single live foetus.

Computerised tomography scan of the brain showed an acute haematoma of 37mm×27mm×45mm (volume of 22mL) in the left temporo-occipital region, with surrounding oedema and 4mm midline shift.

Cerebral angiography showed a left AVM with feeding vessels from the left middle cerebral and posterior cerebral arteries and venous drainage via the superior transverse sinus (Fig. 1).

This AVM was small and assessed as being easily accessible for surgical resection. A multidisciplinary medical team decided to perform a craniotomy for surgical resection of the AVM under general anaesthesia.

A regimen of corticoids was begun 5 days prior to surgery, with the main objective of reducing the cerebral oedema. In the operating room, monitoring included electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, pulse oximetry, capnography and hourly urinary output monitoring. Intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring was established prior to induction of anaesthesia. The obstetrics team decided against foetal heart rate monitoring.

A rapid-sequence induction of anaesthesia with cricoid pressure was performed with fentanyl 150¿g, propofol 160mg and rocuronium 60mg (1mgkg−1) to facilitate tracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation. After induction of anaesthesia, a central venous line was placed in the right internal jugular vein. Anaesthesia was maintained with 60% oxygen, sevoflurane 1–1.5% and remifentanil continuous infusion. Neuromuscular blockade was maintained with rocuronium.

During surgery, the patient remained stable from a haemodynamic and respiratory perspective. The systolic blood pressure was maintained between 110 and 120mmHg, heart rate of 85 beats/min, peripheral oxygen saturation (Spo2) of 99%, PACO2 in the range of 30–35mmHg.

The neurosurgical team reported adequate brain relaxation conditions and no extra measures were required to prevent cerebral oedema. The AVM was successfully removed.

Estimated blood loss was 600mL and 3L of Ringer's solution were infused.1 Surgery took 4h. At the end of the procedure ondansetron 4mg was administered to reduce the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting and the neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine 2mg and atropine 0.8mg.

The patient awoke from general anaesthesia without neurologic deficit and was extubated in the operating room. Postoperative FHR monitoring and ultrasonography were normal. She was discharged from the critical care unit on day 2 and went home on day 10.

DiscussionThe incidence of ICH during pregnancy is approximately 1 per 10,000.2 This condition is associated with a mortality rate of 40%.3 One of the potential causes of ICH in pregnancy are AVMs. Most authors recommend conservative management of unruptured AVMs in pregnant women.4 However, an AVM is generally only diagnosed during pregnancy in the case of rupture. The risk of re-bleeding in pregnant patients is estimated to be about 25–50%.5 This can be explained by both hormonal changes that can lead to a softening of the connective vascular tissue and the physiological increase in cardiac output.5

For this reason, treatment options are limited for pregnant patients. This calls for aggressive and early treatment that provides definitive control over the lesion to prevent rebleeding3,4 which is why conservative management was dismissed.

Therapeutic options include endovascular embolisation, radiosurgery and surgical removal.6 A multimodal therapy with a multidisciplinary approach offers the best clinical results, with high rates of recovery and the prevention of bleeding.6 The treatment regimen should be carefully planned based on the patient's age, neurological condition, and the Spetzler–Martin grade of the AVM.

Embolisation of AVMs as the sole treatment only provides a 20%3 recovery rate. Therefore this is not considered a definitive therapy in most cases. The utility of embolisation of AVMs becomes more apparent when used prior to surgical resection to reduce the size of the AVM.

It causes a reduction of the blood flow in the AVM and subsequently facilitates the surgical removal.6 During interventional neuroradiology, the maximum dose of radiation to the foetus should not exceed 0.5–1rem (10mSievert).5 Foetal exposure may be reduced by radiological protection measures.5 The Onyx® (ev3 Neurovascular, Irvine, CA) liquid embolic agent is an ethylene-vinyl alcohol co-polymer dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).2 Although it is considered to be chemically inert, its safety during pregnancy has yet to be established.2 Subsequently, embolisation of an AVM during pregnancy remains controversial.4

Radiosurgery is based on the application of radiation to the nidus of the AVM to encourage endothelial proliferation that will progressively occlude the malformation in 2 or 3 years. Furthermore, the radiation required for the procedure excludes this therapeutic option in the cases of pregnant patients.6

Neurosurgical resection offers the best treatment option for a ruptured AVM, either alone or in combination with pre-operative embolization.6 The cure rates of surgical resection are around 90%.4 It represents the most definitive treatment, as removing the lesion prevents re-bleeding.5 There are few previously reported cases of AVMs resections during pregnancy. Decision to operate depends on Spetzler & Martin grading system including location, size and venous drainage pattern. In this case, the AVM was accessible and situated in a non-eloquent brain area, being classified as grade III in the Spetzler–Martin grading system.

In light of the low maternal–foetal morbidity and mortality associated with this procedure, surgical removal has become the standard treatment of these rare cases at our institution.

Anaesthetic considerations during pregnancy are governed by maternal–foetal physiology and arterial pressure control.7 The main objectives during surgery were to maintain haemodynamic stability thus ensuring adequate utero-placental perfusion and foetal oxygenation while maintaining an appropriate depth of anaesthesia and avoiding episodes of intracranial hypertension and the risk of re-bleeding.5 Arterial blood pressure should be monitored invasively to maintain close haemodynamic control and cerebral blood flow as well as the uteroplacental perfusion. There are few cases of foetal preservation in the literature where an anaesthetic technique with controlled hypotension has been used during neurological procedures.8 Taking into account the surgical risk of maternal haemorrhage of an accessible AVM versus foetal asphyxiation, this strategy was dismissed. In our case, it was decided to preserve the pregnancy in view of the gestational age so we avoided a mean ABP of less than 70mmHg.9

In pregnants patients with ruptured AVMs, it is priority to determine if there is a neurosurgical emergency10 requiring urgent management independent of gestational age of the patient. If gestational age is advanced,11 it is recommended to end the pregnancy, to allow recovery and subsequently propose a surgical removal of the lesion based on the algorithms.3

The best mode of delivery in patients with untreated AVMs still remains controversial (modified vaginal delivery with forceps or caesarean section). It seems not to modify the foetal or maternal outcome.6 The choice of the anaesthetic technique for caesarean section is influenced by the need to maintain a stable cardiovascular system. Due to the oddity of this condition, no definitive guideliness exist.7 None anaesthetic method is superior to the others.

A regional anaesthetic technique may be preferred if delivery is considered before neurosurgical procedure6 because it allows the neurologic monitoring in an awake patient and it avoids the haemodynamic changes during general anaesthesia. However, complications can occur.

Spinal anaesthesia would provide a dense sympathetic blockade with secondary hypotension which may require vasopressor support. A decrease in BP may lead to nausea and vomiting, which can increase ICP.3

Epidural technique allows incremental local anaesthetic dosing avoiding increases in ICP assuring a gradual haemodynamic changes. However, accidental dural puncture with an 18-G Tuohy needle with subsequent cerebrospinal fluid leak may result in a decrease of the ICP with traction on the dura resulting in rebleeding, or even herniation.3

General anaesthesia would avoid neurological events due to the accidental dural puncture and allow for controlled maternal PACO2 levels in the ranges of 25–30mmHg. Nevertheless, haemodynamic changes can occur during anaesthesia induction. An increase in BP leads to changes in transmural pressures of the AVM raising the risk of rupture.3 Furthermore, advanced pregnants have a higher risk of aspiration and difficult intubation of the trachea. During general anaesthesia it is important to check for vaginal bleeding.6

If the resection of the AVM and the delivery of the foetus are performed in the same surgical procedure, general anaesthesia is mandatory.

In summary, after a multidisciplinary medical team10 assessed the high risk of further bleeding of the lesion associated with high maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality it was decided that surgical excision of the AVM through a craniotomy was the most suitable approach. The role of the anaesthesiologist during craniotomy for excision of an AVM in pregnancy is to ensure maternal cardiovascular stability and uteroplacental perfusion while providing optimal conditions for the neurosurgical procedure.

Patient perspectiveThe patient experienced anaesthetic management performed as safer for her and the foetus.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics committeeWe have the approval of the ethics committee.

Identification dataPatient data are not identified.

FundingNo external funding and no competing interests declared.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero-Domínguez R, Rubio-Romero R, López-Herrera-Rodríguez D, Federero F, Jiménez I. Manejo anestésico para craneotomía en paciente gestante con ruptura de malformación arteriovenosa cerebral: reporte de caso. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:57–60.