Introduction: The perioperative management of patients receiving chronic treatment with warfarin and scheduled for invasive, elective or emergency procedures is a difficult and frequently arising problem in clinical practice. The lack of clear management guidelines and the indiscriminate use of the temporary replacement with unfractionated heparin creates delays, increases costs and unnecessarily prolongs the length of hospital stay.

Objectives: To review current trends and their supporting evidence of temporary replacement ("bridging") during the pre-operative period, emphasizing the use of low-molecular-weight heparins on an outpatient basis.

Methodology: PubMed search of evidence-based management guidelines, expert consensus and original trials.

Results: Three evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, together with multiple narrative expert reviews, four of them recently published, were identified. Clinical trials found in the surgical setting were purely observational. Although there are comparative studies, none of them apply to the surgical setting.

Discussion: Management evidence is limited and expert consensus guidelines are inconsistent.

Conclusions: There is suggestive, though non-conclusive evidence supporting the use of low-molecular-weight heparins for temporary replacement ("bridging") of pre-operative anticoagulation on an outpatient basis. There is a need to conduct well-designed comparative studies in the perioperative setting. Guidelines for anticoagulation management in elective and emergency cases are proposed on the basis of the information available, expressed in the form of a simple and innovative graphic algorithm applicable to the Colombian situation.

© 2012 Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación. Published by Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Introducción: El manejo de la anticoagulación perioperatoria en pacientes tratados crónicamente con warfarina y programados para procedimientos invasivos, electivos y urgentes es un problema clínico frecuente y de difícil manejo. La ausencia de esquemas de manejo claros y el uso indiscriminado de remplazo transitorio con heparina no fraccionada genera demoras, sobrecostos y días de hospitalización innecesarios.

Objetivos: Revisar las tendencias actuales y evidencia que las soporta, concerniente al remplazo transitorio de la anticoagulación en el preoperatorio ("puenteo"), con énfasis en el uso de heparinas de bajo peso molecular, de manera ambulatoria.

Metodología: Se realizó una búsqueda en PubMed de las guías de manejo basadas en la evidencia, consensos de expertos y estudios originales al respecto.

Resultados: Se identificaron tres guías de práctica clínica, basadas en la evidencia y múltiples revisiones narrativas por expertos, cuatro de ellas recientes. Los estudios clínicos encontrados en ámbito quirúrgico, son puramente observacionales. Existen estudios comparativos, pero en escenarios no quirúrgicos.

Discusión: La evidencia respecto al manejo es limitada y las guías por consenso de expertos son inconsistentes.

Conclusiones: Existe evidencia sugestiva, aunque no concluyente, que soporta la utilidad de las heparinas de bajo peso molecular; en el remplazo transitorio y ambulatorio de la anticoagulación en el preoperatorio ("puenteo"). Se necesitan estudios comparativos, bien diseñados, realizados en el ámbito perioperatorio. Con base en la información disponible, se proponen algunos lineamientos con respecto al manejo de anticoagulación en casos electivos y urgentes, expresándolos gráficamente en un algoritmo novedoso y sencillo.

© 2012 Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación. Publicado por Elsevier. Todos los derechos resevados.

Approximately 1.4% of the adult population requires continuous oral anticoagulation,1 and this percentage may increase in the future.2 Moreover, at least 10% of this population faces the possibility of a surgical intervention every year.3 Maintaining the anticoagulation effect until the time of surgery or during the procedure may result in excess bleeding;3,4 on the other hand, interrupting the treatment during the perioperative period increases the risk of thromboembolic events.5,6 This creates a very common and difficult clinical problem that has already been the focus of attention in this journal.7,8

In order to overcome the problem, warfarin is usually interrupted several days prior to the intervention and replaced with the temporary use of anticoagulants of shorter action in order to minimize the time without anticoagulation effect. This bridging practice has been based traditionally on the use of unfractionated heparin (UH) as an intravenous infusion; however, this involves unnecessary hospitalizations and additional costs for patients, institutions and health systems alike.

A recent trend consists of the use of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH). Given the ease of subcutaneous administration and the predictability of their effect, they may be used on an outpatient basis and reduce costs and hospital stay. However, there are doubts and some confusion among clinicians involved in perioperative management regarding their effectiveness, safety and form of use.

Some scientific societies worldwide have gathered the literature available in an attempt at formulating management schemes in the form of evidence-based clinical guidelines,9-11 and there are also numerous expert narrative reviews on the subject.12-15 Unfortunately, there is no consensus regarding the recommendations, and the proposed schemes tend to be exceedingly complex or inapplicable.

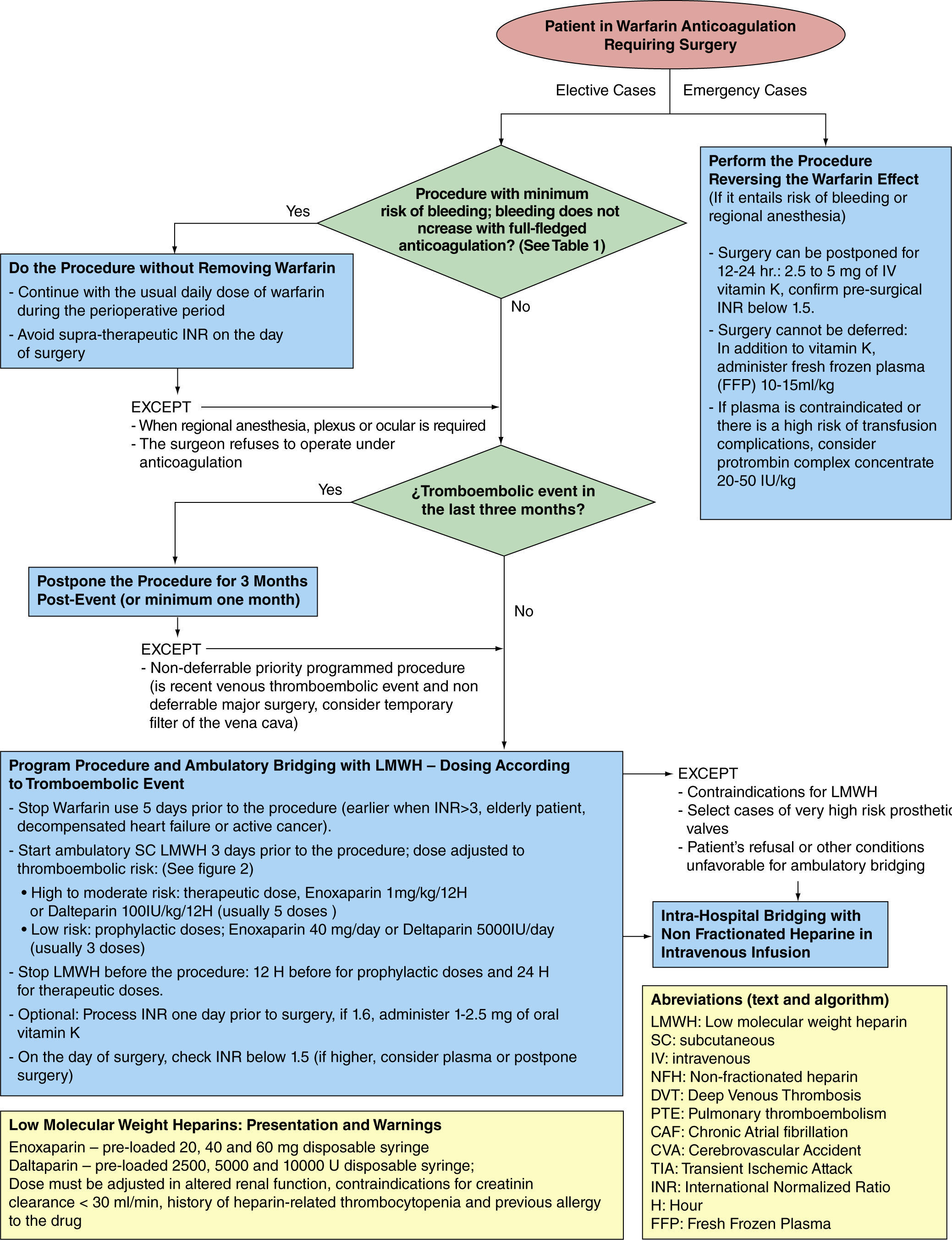

The aim of this paper is to mention the most relevant evidence supporting current management trends for elective and emergency cases in the preoperative period that usually involve the treating anesthetist, and to propose a simple algorithm (fig. 1) that tries to summarize the international recommendations, and that may be applicable in the Colombian setting.

Considerations of the variables and risksAmong multiple factors that need to be considered, the two most important variables in decision-making during the preoperative period are the risk of bleeding associated with the procedure, and the risk of thromboembolic events associated with the patient. The former determines the need for timely interruption of warfarin, and the latter affects the relevance of bridging and the dose.

Risks must be assessed in terms of probability and clinical repercussions (morbidity and mortality).15 Using risk prediction scales, risks are classified according to severity in order to establish relevant cut-off points for decision-making. At present, predicting the risk of thromboembolic events has been more consistent than predicting the risk of bleeding.

Prediction of the risk of perioperative bleedingIt has been estimated that the risk of death associated with major bleeding due to cumadin ranges between 3% and 9%.4,9 The effect on morbidity is also significant in terms of emergency surgery, adverse cardiac and respiratory events, increased risk of infection, and potential long-term consequences associated with the healing process, and chronic pain.4,14 Moreover, bleeding may delay the restart of anticoagulation, increasing the time at risk for thromboembolic events.16

Depending on the proposed procedure, multiple scales have been designed for predicting perioperative bleeding,12,14 but they show serious inconsistencies in terms of the number of groups and the cut-off points. More worrisome still is their low predictive value, perhaps due to the wide variety of additional factors involved.

Consequently, careful classification of a procedure in a given group would hardly be relevant for preoperative planning. In contrast, it is more practical to establish a cut-off point with implications for management, and to separate the procedures that may be undertaken without interrupting warfarin from those that require interruption and, potentially, bridging.

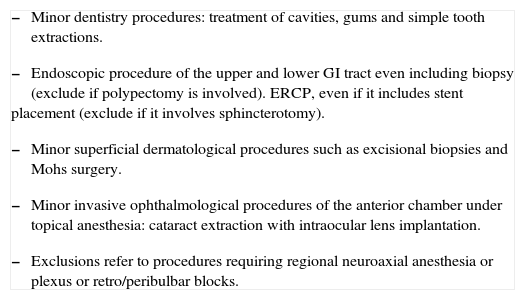

Practice based on the risk of bleedingThere are minimally invasive procedures in dentistry, ophthalmology, dermatology and endoscopic practice that are usually associated with negligible bleeding which does not increase with full oral anticoagulation.

The way to proceed, based on prospective randomized studies in dentistry,17,18 as well as on prospective cohort studies in the other areas,19-21 would be to continue with full anticoagulation during the perioperative period without using bridging agents, all in accordance with the guidelines and expert opinions.9-15 Not all "minor surgeries" may be included in this group, but only those listed in table 1. Exceptions to the rule include the surgeon's reluctance to perform the procedure with the patient under anticoagulation, and procedures planned for regional anesthesia (neuroaxial, plexus or ocular blocks).22,23

Procedures associated with a minimal risk of bleeding which does not increase with full anticoagulation

|

Fuente: Autores a partir de: Dunn AS(4), Douketis JD(9), Jeske AH (17), Bacci C(18) , Eisen GM (19), Hirschman DR (20), Katz J (21), Kallio H (22), Horlocker TT (23)

All other surgical procedures involve some risk of bleeding where the severity and clinical repercussions may increase as a result of oral anticoagulation.3,4 On the other hand, other procedures may cause minor bleeds in terms of quantity, but with serious local repercussions that may increase with anticoagulation, such as those involving the central nervous system, the posterior chamber of the eye, polypectomies larger than 2cm,25 prostate biopsies,26 pacemaker or defibrillator implantations.27

Warfarin must be interrupted on a timely basis, in accordance with the guidelines, practically for every elective procedure involving a risk of bleeding (except for those listed in table 1) or whenever regional anesthesia is planned.9-15 The additional need for bridging and the possible bridging regimes will be discussed later.

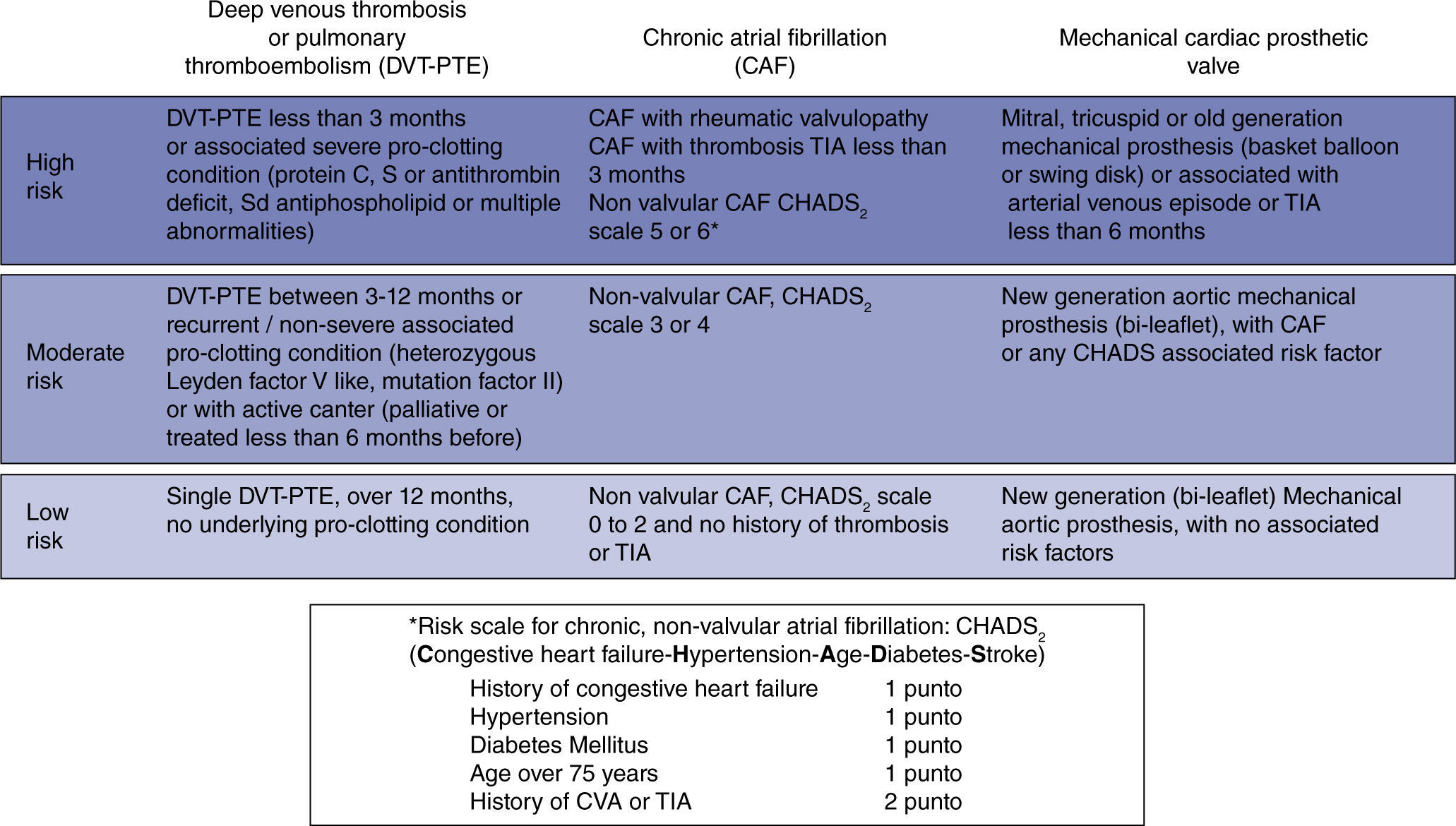

Predicting the risk of preoperative thromboembolic eventsThe clinical conditions that warrant continuous anticoagulation with warfarin are mainly three: chronic atrial fibrillation (AF), prosthetic heart valves, and a history of venous or pulmonary thromboembolism (DVT-PTE). They each represent a heterogenous group of thromboembolic risk that varies depending on the history of prior events, comorbidities, and associated conditions.

In chronic AF, the risk increases with a valve substrate; if not, the risk depends on associated factors quantified according to the CHADS2 scale.28,29 The risk with prosthetic valves increases when they are of an older generation, when they are in the mitral or tricuspid position, and as a result of other factors similar to CHADS2.11,30 In DVT or PTE, the risk varies according to the time elapsed since the event, the number of recurrences, and the presence and severity of underlying thrombophilic conditions.31,32

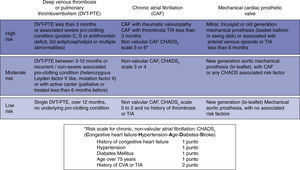

For practical considerations, these conditions may be regrouped on a baseline thromboembolic risk scale according to the annual probability of a patient having an event if not anticoagulated. Consequently, the risk may be classified as low if it is lower than 4%; moderate if it ranges between 4% and 10%; and high if it is greater than 10% (fig. 2).9 The clinical impact must also be taken into consideration. In that regard, the impact of an arterial thrombosis (chronic AF or prosthetic valves) is greater in terms of quality of life and mortality, when compared to venous thrombosis (DVT-PTE).32,33

In mathematical terms, the risk for every day that goes by without anticoagulation during the perioperative period would be equal to the annual baseline risk divided by 365.9 Some authors mention an additional risk element related to a transient hypercoagulability condition resulting from the abrupt interruption of warfarin.34 Although the type of surgery affects the risk of a thromboembolic event,35 it is not an additional factor that would need to be considered during the preoperative period.

Recently, an analytical decision model suggests a cutoff point above 5.6% for the annual baseline risk in order to consider bridging,36 which could be equated to the moderate and high risk groups.

Strategies for reducing the preoperative risk of thromboembolismAfter a recent venous thromboembolic event, the risk of recurrence drops dramatically during the first three months, hence the suggestion by some authors of deferring nonpriority surgeries for at least 1month, ideally 3months. This suggestion could be extended to recent arterial or cardioembolic events.28 The placement of a temporary caval filter is a possibility to consider in very recent DVT and in nondeferrable major surgery.32,37

Regarding the true usefulness of perioperative bridging, there are no prospective, randomized or placebo-controlled studies to date showing reliable information about its efficacy, safety, dose or comparative differences between potential drugs and regimes. The existing evidence is derived from good-quality studies, but there is a tendency to extrapolate it to the perioperative setting from non-surgical situations and lower quality studies (purely observational).

In non-surgical areas, there is good-quality evidence supporting the usefulness of LMWH for the management of DVT-PTE, and for reducing the risk of recurrence after an event. They have been shown to lend themselves to outpatient management because of their safety profile, and they have even been shown to be better than UFH.32 The evidence supporting the use of LMWH for the control of arterial or cardioembolic events is less strong, although there is indirect evidence suggesting its usefulness in the management of chronic AF,38 subacute ischemic stroke,39 and also in cases of prosthetic valves, this is a more controversial issue.40

In the perioperative setting, there are no randomized controlled trials providing reliable evidence on the usefulness of bridging with LMWH; however, there are multiple descriptive prospective cohort studies showing a low mean rate of thromboembolic events (1%) and major bleeding (3%). In prosthetic valves, there are at least 14 studies with 1,300 patients showing an overall rate of thromboembolic events of 0.83%; in chronic AF, 10 studies with 1,400 patients show a rate of 0.57%; and in DVT-PTE, 9 studies with 500 patients show an overall rate of 0.6%. The data were consolidated in a recent review by the ACCP.9 There are two ongoing good-quality studies that are expected to provide more reliable information by 2014.41,42

The usefulness of unfractionated heparin (UFH) as a perioperative bridging agent is also supported by a smaller number of purely observational studies. A multi-center prospective non-randomized cohort study comparing perioperative bridging with UFH versus LMWH did not show significant differences in terms of thromboembolism or bleeding rates.43 Although no differences were found in a subgroup analysis of prosthetic valves,44 some cardiology societies still express their reservations regarding the use of LMWH in high-risk prosthetic valves.11

Regarding the bridging dose of LMWH, evidence-based guidelines.9-11 are consistent in suggesting therapeutic doses of LMWH in high-risk groups, and prophylactic doses or no bridging in low-risk groups, although there are some inconsistencies in relation to the moderate risk of venous thromboembolism.

Out of simplicity and due to medical and legal reasons, an attempt should be made at unifying the recommendations around a more aggressive approach as that suggested by the best known guidelines: prophylactic doses for low-risk groups, and therapeutic doses for moderate and high-risk groups.9

Practical protocol for pre-operative outpatient bridging with LMWHBased on pharmacological studies of these drugs,45 clinical trials on perioperative bridging16 and the guidelines mentioned above, the following parameters could be suggested: warfarin interruption 4 to 5days prior to surgery9-15 (although a longer time period might be required in certain situations such as, an INR greater than 3, an elderly patient, decompensated heart failure and active cancer);46 initiation of LMWH 24 to 36 hours after the last dose of warfarin (3days before the procedure).9-15 The most commonly used drugs, included in the Colombian mandatory health plan, are cited in the algorithm (fig. 1).

A twice-daily dose is preferable over single daily dose regimes for therapeutic doses.47 Prophylactic and therapeutic treatment must be interrupted 12 hours and 24 hours before the procedure or regional anesthesia, respectively.9-15,23 Given the erratic clearance of warfarin, an INR lower than 1.5 must be documented before surgery;9-15 some authors suggest measuring the INR one day prior to surgery, in order to allow the possibility to correct an abnormal result with low-dose oral vitamin K (1–2.5mg), thus avoiding the need to postpone surgery or the unwarranted administration of plasma.48

Warfarin reversion in emergency casesIn cases of emergency surgery, a dose of 2.5-5mg of vitamin K given orally or as a slow intravenous infusion may revert the anticoagulation effect of warfarin within 12 to 24 hours.49 When the surgery is to be performed within a shorter period of time, it is important to consider, aside from vitamin K, a dose of 10ml/kg-15ml/kg of fresh frozen plasma (FFP).50 However, its processing and administration take time, and it is also associated with transfusion risks (transfusion acute lung injury or TRALI, excess fluid burden, risk of infection, anaphylactic reactions); moreover, it might be insufficient in reverting hyper-anticoagulation states.

The use of prothrombin complex concentrate has been introduced recently at a dose of 25IU/kg-50IU/kg that appears quite promising, with comparative advantages over the use of FFP, it being faster, safer and more effective, and lacking the adverse effects associated with the use of FFP. However, its use is still limited because of its high cost and the scant evidence in the perioperative setting.51,52

Competing InterestsNone declared.

Funding sources: The author's own resources.