Functional oropharyngeal dysphagia affects more than 30% of all stroke patients. The variability of the clinical presentation of the disorder and subjective patient perception result in a certain percentage of undiagnosed cases of dysphagia – this in turn posing a serious problem due to the associated complications.1 Screening methods are therefore necessary to identify individuals with swallowing difficulties. In our setting these are mainly elderly individuals and patients with neurological diseases.2

Dysphagia may result in very serious and very frequent nutritional and respiratory complications. Aspiration pneumonia secondary to dysphagia is the leading cause of death in stroke patients during the first year of follow-up after hospital discharge.2,3

On the other hand, dysphagia has a direct impact upon patient nutritional status. Malnourished patients are at increased risk for short- and long-term disability and dependence after stroke.4

The relevance of the clinical repercussions of dysphagia in these patients and our perception of scant awareness of the problem on the part of the healthcare staff led us to conduct an observational descriptive study of a cohort of patients admitted to the Stroke Unit of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León (CAULE) during a two-month period. The aim was to establish the prevalence of dysphagia in stroke patients and its possible clinical repercussions. Screening for dysphagia was carried out with the Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) (score ≥3: the patient may have problems swallowing safely and effectively, and is considered positive for dysphagia), which has been validated in the Spanish population,5 and screening for malnutrition was made with the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) (score ≥2: high risk of malnutrition).3 Likewise, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) (which affords a quantitative assessment of neurological impairment after acute stroke) was used to assess stroke severity,6 while the Rankin scale7 was used to globally assess the degree of physical disability after stroke. This scale is divided into 7 levels ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

The patients were evaluated within the first 72h after stroke and were re-examined on the day of discharge.

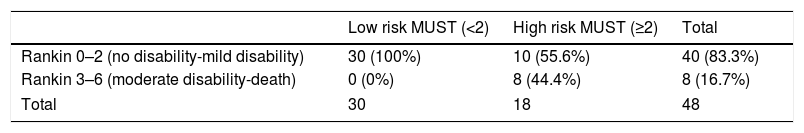

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures performed in human subjects were approved by the local Clinical Research Ethics Committee. We analyzed the data corresponding to 48 patients admitted to the Stroke Unit of the CAULE in the months of March and April 2016. Two patients that died in the first 24h after stroke were excluded. A little over one-third of the patients (37.5%) presented high nutritional risk upon admission (MUST score≥2). These were the patients with the most severe stroke according to the NIHSS at the time of hospital admission (MUST score≥2: 14 NIHSS score versus MUST score<2 NIHSS score 2.34; p<0.005). The patients with high malnutrition risk also showed longer hospital stay: 12.33 days versus 8.59 days (p=0.047). It is also significant that the patients with high nutritional risk according to the MUST upon admission suffered greater physical disability according to the Rankin scale at discharge (p<0.001) (Table 1). There were no differences in clinical outcomes (MUST and EAT-10 risk scores) according to patient age at the time of admission to the Stroke Unit.

Mean percentage body weight loss after admission was 2.08% (standard deviation [SD]: 2.01). Just over one-half of the patients (51.1%) lost more than 2% of their weight in the first week – this being considered an important weight loss. Weight loss in excess of the median value of 2% was associated to longer hospital stay: 7.41 days (SD: 1.00) versus 12.63 days (SD: 1.54) (p=0.008).

As regards dysphagia, 14.6% of our patients presented an EAT-10 score≥3. Patients with EAT-10 scores positive for dysphagia had longer hospital stays: 12 versus 9.77 days. It is also significant that patients with dysphagia suffered comparatively more physical disability at discharge (28.57% of those at risk of dysphagia presented at least moderate disability at discharge versus 2.78% of those screening negative for dysphagia; p=0.01). Dysphagia at discharge was also associated to weight loss in excess of 2%.

In conclusion, our data confirm that a large percentage of stroke patients are at high risk of malnutrition, and that this in turn is associated with more severe stroke. Both malnutrition and dysphagia are correlated to longer hospital stay and a poorer functional prognosis at patient discharge. Therefore, and as recommended by the latest international guidelines, we consider that screening for both malnutrition and dysphagia should not be overlooked.8,9

Please cite this article as: Fernández Martínez P, Barajas Galindo DE, Arés Luque A, Rodríguez Sánchez E, Ballesteros-Pomar MD. Repercusiones clínicas de la disfagia y la desnutrición en el paciente con ictus. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:625–626.