Women with history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are at increased risk for diabetes. Ethnicity may modify such risk, but no studies have been conducted in our environment. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes one year after delivery in women with GDM and in a multiethnic background and to identify the associated factors.

Patients and methodsA retrospective analysis of a prospective, observational cohort of women with GDM who attended annual postpartum follow-up visits at Hospital del Mar from January 2004 to March 2016.

ResultsThree hundred and five women attended postpartum follow-up visits. Of these, 47.2% were Caucasian, 22% from South-Central Asia, 12% from Latin America, and 10% from Morocco and East Asia. Incidence rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes in these patients were 5.2 and 36.6%, respectively. In a multivariate analysis, non-Caucasian origin (OR=3.15, 95% CI [1.85–5.39]), recurrent gestational diabetes (OR=2.26, 95% CI [1.11–4.59]), and pre-pregnancy body mass index (OR=1.09, 95% CI [1.04–1.15]) were independent predictors of impaired glucose tolerance.

ConclusionsIn a multiethnic Spanish population of women with GDM, incidence of impaired glucose tolerance in the first year after delivery was 41.8%, with a three-fold increased risk for women of non-Caucasian ethnicity.

Las mujeres con antecedentes de diabetes mellitus gestacional (DMG) tienen mayor riesgo de diabetes. Si bien la etnia puede modificar este riesgo, no disponemos de estudios específicos en nuestro entorno. El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la incidencia de diabetes mellitus tipo 2 y prediabetes en el primer año posparto en mujeres con DMG y en un entorno multiétnico e identificar los factores asociados.

Pacientes y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de una cohorte observacional prospectiva de mujeres con DMG que acudieron al control posparto anual en el Hospital del Mar, entre enero de 2004 y marzo de 2016.

ResultadosTrescientas cinco mujeres asistieron a las revisiones posparto. De estas, un 47,2% fueron caucásicas, un 22% del centro-sur de Asia, un 12% fueron de origen hispano y un 10% procedían de Marruecos y del este de Asia. La incidencia de diabetes mellitus tipo 2 y de prediabetes fue del 5,2 y el 36,6%, respectivamente. Los factores asociados al metabolismo alterado de la glucosa fueron la etnia no caucásica (OR=3,15, IC 95% [1,85-5,39]), los antecedentes previos de DMG (OR=2,26, IC 95% [1,11-4,59]) y el índice de masa corporal previo al embarazo (OR=1,09, IC 95% [1,04-1,15]).

ConclusionesEn una población española de origen multiétnico, la incidencia de alteraciones del metabolismo hidrocarbonado en el primer año posparto de mujeres con antecedentes de DMG fue del 41,8%, siendo el riesgo 3 veces superior en las mujeres no caucásicas que en las caucásicas.

The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) varies according to ethnic origin, the percentage of immigrant women in the study population, and the diagnostic criteria used. In studies involving a predominantly Caucasian population, the prevalence of GDM is 2–3%, while in multiethnic populations this figure can increase to 14%.1–4 In Spain, GDM is present in 3–9% of all pregnancies.5–7

Gestational diabetes mellitus implies not only an increased risk of obstetric complications requiring specific monitoring and treatment,8,9 but also an increased risk of altered carbohydrate metabolism3,4 and cardiovascular disease in the postpartum follow-up.10–12 In addition, a non-Caucasian ethnic origin has been described as a risk factor for the development of diabetes. In this regard, the United States National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has reported a prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) of 7.8% in Caucasian women, 13.5% in Hispanic women and 15.4% in Afro-American women.13 Not surprisingly, ethnicity constitutes a risk factor for some degree of altered carbohydrate metabolism in the postpartum control of women with prior GDM.14,15 Several predictors of diabetes have been described in women who have previously experienced GDM: glucose levels in the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) during pregnancy,4 the use of insulin in pregnancy,14,16,17 the body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy,18 and a family history of DM2.16 Many of these predictors of diabetes have been confirmed in studies of the Spanish population,19,20 but these publications did not include immigrant women from different ethnic backgrounds. Immigration has been one of the most notable socio-sanitary phenomena in Spain over recent decades. According to the latest report of the Spanish National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]), a total of 5,131,591 foreign nationals were resident in Spain in June 2017, representing 11% of the total Spanish population. Furthermore, about 40% of this immigrant population is of fertile age.21 Studies involving the Spanish immigrant population are therefore needed to assess the influence of ethnicity upon the development of alterations in carbohydrate metabolism. For this reason, the present study was carried out to determine the incidence of alterations in hydrocarbon metabolism in the first year after delivery among women with a history of GDM, and to identify the predictive factors in a multiethnic population in Spain.

Patients and methodsA retrospective analysis was made of a prospective cohort of women with GDM seen consecutively at the Endocrinology outpatient clinic of Hospital del Mar (Barcelona, Spain) between January 2004 and March 2016. Gestational diabetes mellitus was diagnosed based on the criteria of the National Diabetes Data Group,22 and patient control was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Management Guide of the Spanish Group of Diabetes and Pregnancy (Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo).23 We included pregnant women with prenatal follow-up and delivery who reported for the control visit during the first year after delivery. The exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies and a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

A total of 305 women underwent a postpartum OGTT. Of these, 47.2% were Caucasian, 22% were from Central-South Asia (India and Pakistan), 12% were of Hispanic origin (Central and South America), 10% were from Morocco, and 10% were from East Asia (mainly China).

Following the GDM protocol of our centre, the women were given appointments for clinical and biochemical re-evaluation during the first year postpartum, including a 75g OGTT. A structured interview was used to collect the following data: age, family history of diabetes, personal history of GDM and macrosomia in previous pregnancies, and the BMI prior to pregnancy. Pregnancy and childbirth information and the neonatal characteristics were compiled from the medical records.

The venous blood extractions were performed after 12h of fasting. Seventy-five grams of glucose were administered with a commercial preparation, and the blood extractions were performed before and 2h after the OGTT. Blood glucose was measured using the oxidase method. The diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes (abnormal fasting blood glucose and abnormal glucose tolerance [AGT]) was based on the plasma glucose levels under fasting conditions and 2h after the OGTT, following the 2010 criteria of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).24

Macrosomia was defined as a newborn infant weight of over 4000g.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital del Mar.

Statistical analysisData were expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) in the case of continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages in the case of categorical variables. The Student t-test was used to study differences in quantitative variables when comparing two groups, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc analysis was applied for multiple comparisons among more than two groups. The chi-squared or Fisher exact test was used to assess the degree of association between categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was subsequently used to analyse factors independently associated with altered glucose metabolism. The multivariate analysis included those variables that were found to be significant in the univariate analysis (the pregestational BMI, ethnicity, nulliparity, a history of GDM in previous pregnancies, insulin treatment and glycosylated haemoglobin [HbA1c] in the third trimester of pregnancy), and also other factors previously described in the literature (a family history of diabetes). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 15.0 statistical package for MS Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

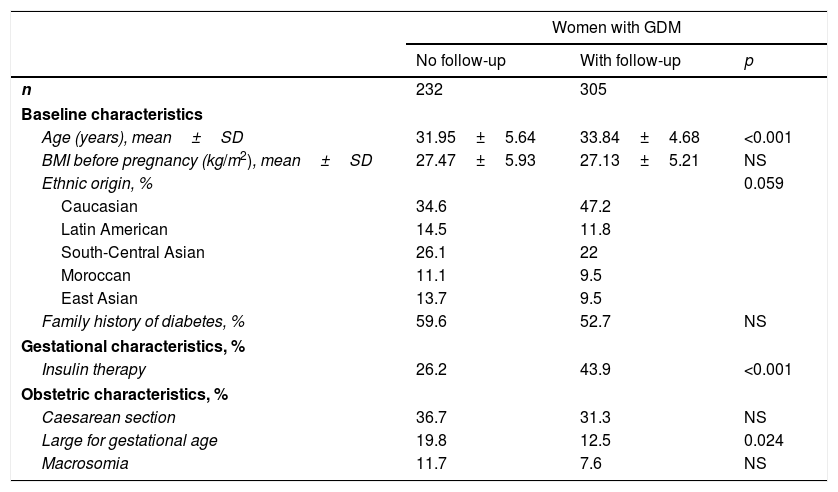

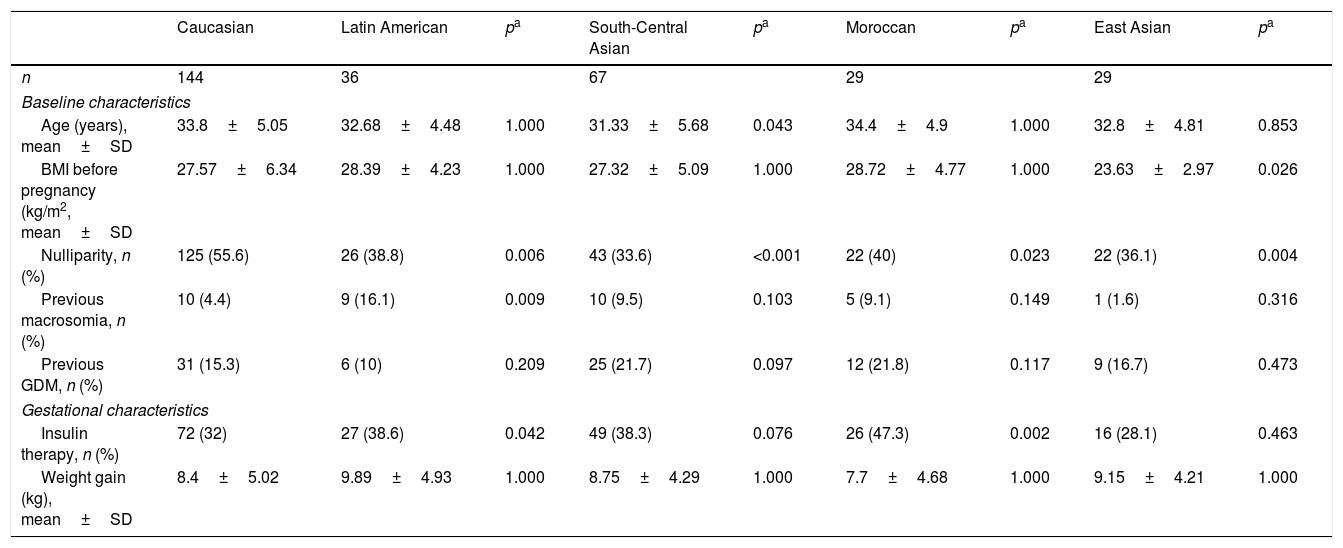

ResultsOf the 537 women diagnosed with GDM during the study period, 306 (56.8%) reported for subsequent clinical follow-up at two and 12 months postpartum. The clinical characteristics of these patients are summarised in Table 1. Women attending postpartum follow-up were older (33.84±4.68 vs. 31.95±5.64 years; p<0.001) and more frequently Caucasian (p=0.059) than women not attending postpartum follow-up. A total of 52.8% of the women subjected to postpartum control were of non-Caucasian origin, the largest group corresponding to women from Central-South Asia (22%). Twelve percent of the women were from Latin America, 10% from East Asia and 10% from Morocco. The main characteristics of the 5 ethnic groups are shown in Table 2. Compared to Caucasian women, those from East Asia had a lower BMI (23.63±2.97 vs. 27.57±6.34kg/m2; p<0.001); insulin treatment during pregnancy was more common in Moroccan women (47.3% vs. 32%; p=0.002) and Hispanics (38.6% vs. 32%; p=0.042); and Moroccan women had more infants with macrosomia (20% vs. 5.8%; p=0.003).

Clinical and obstetric characteristics of the women with gestational diabetes mellitus who did and did not undergo postpartum testing.

| Women with GDM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No follow-up | With follow-up | p | |

| n | 232 | 305 | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 31.95±5.64 | 33.84±4.68 | <0.001 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2), mean±SD | 27.47±5.93 | 27.13±5.21 | NS |

| Ethnic origin, % | 0.059 | ||

| Caucasian | 34.6 | 47.2 | |

| Latin American | 14.5 | 11.8 | |

| South-Central Asian | 26.1 | 22 | |

| Moroccan | 11.1 | 9.5 | |

| East Asian | 13.7 | 9.5 | |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 59.6 | 52.7 | NS |

| Gestational characteristics, % | |||

| Insulin therapy | 26.2 | 43.9 | <0.001 |

| Obstetric characteristics, % | |||

| Caesarean section | 36.7 | 31.3 | NS |

| Large for gestational age | 19.8 | 12.5 | 0.024 |

| Macrosomia | 11.7 | 7.6 | NS |

SD: standard deviation; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index; NS: nonsignificant.

Clinical and obstetric characteristics of the women with gestational diabetes mellitus corresponding to 5 different ethnic origins.

| Caucasian | Latin American | pa | South-Central Asian | pa | Moroccan | pa | East Asian | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 144 | 36 | 67 | 29 | 29 | ||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 33.8±5.05 | 32.68±4.48 | 1.000 | 31.33±5.68 | 0.043 | 34.4±4.9 | 1.000 | 32.8±4.81 | 0.853 |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2, mean±SD | 27.57±6.34 | 28.39±4.23 | 1.000 | 27.32±5.09 | 1.000 | 28.72±4.77 | 1.000 | 23.63±2.97 | 0.026 |

| Nulliparity, n (%) | 125 (55.6) | 26 (38.8) | 0.006 | 43 (33.6) | <0.001 | 22 (40) | 0.023 | 22 (36.1) | 0.004 |

| Previous macrosomia, n (%) | 10 (4.4) | 9 (16.1) | 0.009 | 10 (9.5) | 0.103 | 5 (9.1) | 0.149 | 1 (1.6) | 0.316 |

| Previous GDM, n (%) | 31 (15.3) | 6 (10) | 0.209 | 25 (21.7) | 0.097 | 12 (21.8) | 0.117 | 9 (16.7) | 0.473 |

| Gestational characteristics | |||||||||

| Insulin therapy, n (%) | 72 (32) | 27 (38.6) | 0.042 | 49 (38.3) | 0.076 | 26 (47.3) | 0.002 | 16 (28.1) | 0.463 |

| Weight gain (kg), mean±SD | 8.4±5.02 | 9.89±4.93 | 1.000 | 8.75±4.29 | 1.000 | 7.7±4.68 | 1.000 | 9.15±4.21 | 1.000 |

SD: standard deviation; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index.

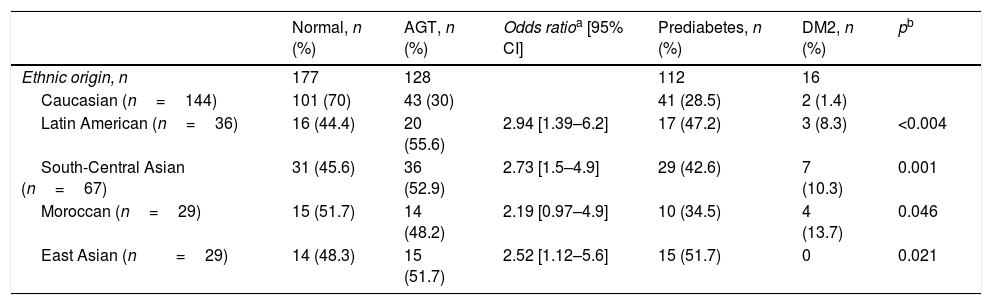

Of the 305 women who participated in the postpartum follow-up, 128 (41.8%) presented altered glucose metabolism as shown by the OGTT results, based on the criteria of the American Diabetes Association 2010: 16 (5.2%) had DM2 and 112 (36.6%) had prediabetes. Of these, 68 (22.2%) presented abnormal fasting blood glucose, 26 (8.5%) AGT, and 18 (5.9%) both. The incidence of altered glucose metabolism among the non-Caucasian women was almost double that seen in the Caucasians, with a higher incidence of DM2 among the former (Table 3).

Ethnic differences in glucose tolerance in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus.

| Normal, n (%) | AGT, n (%) | Odds ratioa [95% CI] | Prediabetes, n (%) | DM2, n (%) | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic origin, n | 177 | 128 | 112 | 16 | ||

| Caucasian (n=144) | 101 (70) | 43 (30) | 41 (28.5) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| Latin American (n=36) | 16 (44.4) | 20 (55.6) | 2.94 [1.39–6.2] | 17 (47.2) | 3 (8.3) | <0.004 |

| South-Central Asian (n=67) | 31 (45.6) | 36 (52.9) | 2.73 [1.5–4.9] | 29 (42.6) | 7 (10.3) | 0.001 |

| Moroccan (n=29) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (48.2) | 2.19 [0.97–4.9] | 10 (34.5) | 4 (13.7) | 0.046 |

| East Asian (n=29) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (51.7) | 2.52 [1.12–5.6] | 15 (51.7) | 0 | 0.021 |

DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AGT: abnormal glucose tolerance.

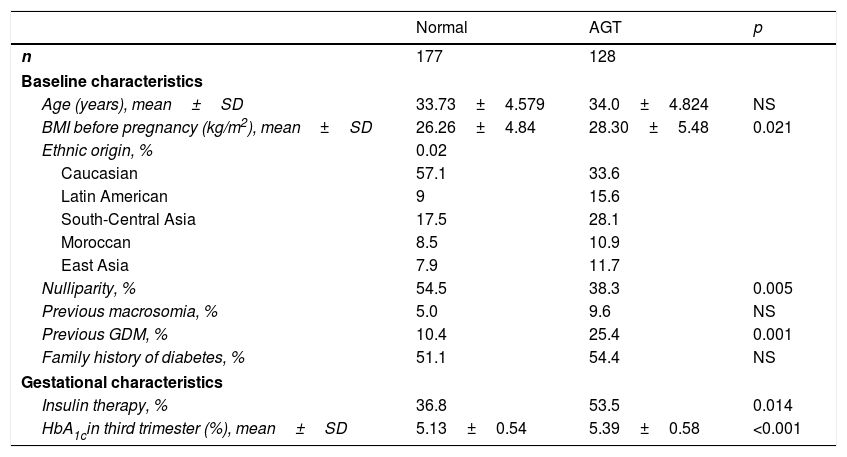

The maternal, gestational and neonatal characteristics of the women with or without altered glucose metabolism at postpartum control are reported in Table 4. Women with altered glucose metabolism were more often of non-Caucasian origin and had higher pregestational BMI. Furthermore, they more often needed insulin treatment during pregnancy for GDM control and started it earlier in pregnancy (29.61±4.74 vs. 31.57±4.43 weeks; p=0.014). They also underwent a greater number of caesarean sections (32.7% vs. 18.4%; p=0.038) compared to those without altered glucose metabolism in the postpartum period. Lastly, the women with altered glucose metabolism had higher postpartum triglyceride levels (105.73±57.09 vs. 88.93±41.38mg/dl; p=0.05) and lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations (53.13±12.53 vs. 59.33±12.52mg/dl; p=0.009) than those without altered glucose metabolism after one year of follow-up.

Clinical and obstetric characteristics of the women with normal glucose metabolism and abnormal glucose tolerance after pregnancy.

| Normal | AGT | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 177 | 128 | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 33.73±4.579 | 34.0±4.824 | NS |

| BMI before pregnancy (kg/m2), mean±SD | 26.26±4.84 | 28.30±5.48 | 0.021 |

| Ethnic origin, % | 0.02 | ||

| Caucasian | 57.1 | 33.6 | |

| Latin American | 9 | 15.6 | |

| South-Central Asia | 17.5 | 28.1 | |

| Moroccan | 8.5 | 10.9 | |

| East Asia | 7.9 | 11.7 | |

| Nulliparity, % | 54.5 | 38.3 | 0.005 |

| Previous macrosomia, % | 5.0 | 9.6 | NS |

| Previous GDM, % | 10.4 | 25.4 | 0.001 |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 51.1 | 54.4 | NS |

| Gestational characteristics | |||

| Insulin therapy, % | 36.8 | 53.5 | 0.014 |

| HbA1cin third trimester (%), mean±SD | 5.13±0.54 | 5.39±0.58 | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; BMI: body mass index; NS: nonsignificant; AGT: abnormal glucose tolerance.

In the multivariate analysis, a non-Caucasian origin (OR=3.15, 95% CI [1.85–5.39]), a history of GDM (OR=2.26, 95% CI [1.11–4.59]) and the pregestational BMI (OR=1.09, 95% CI [1.04–1.15]) were the factors found to be independently and significantly associated with the development of altered glucose metabolism at postpartum follow-up.

DiscussionThis study for the first time describes the incidence of altered glycemia in the first year postpartum of a multiethnic cohort of women with GDM in the Spanish population. The main findings were the high incidence of altered carbohydrate metabolism in non-Caucasian women compared to Caucasians one year after delivery (55% vs. 30%), and the identification of ethnicity as the main predictor of the development of abnormal glucose tolerance (AGT) (OR=3.2). Other already known and independently associated factors were a history of GDM and the BMI prior to pregnancy.

Women with a history of GDM are 7 times more likely to develop diabetes than those with normal glycemia values during pregnancy.3 Our results revealed an incidence of GDM of 41.8% in the first year after delivery, with a prediabetes and DM2 incidence of 36.6% and 5.2%, respectively. Previous studies in the first year postpartum after GDM describe a variable incidence of AGT ranging from 7% to 35%,16,19,25–28 depending on the diagnostic criteria, follow-up period and ethnic group involved.4 Studies in a Spanish and Caucasian population have described a prevalence of AGT of 25.3% four months after delivery, with 10.4% AGT and 5.8% abnormal fasting glycemia.19 In Sweden, Aberg et al.25 reported an incidence of AGT and prediabetes of 31% and 22%, respectively, one year after delivery in a group of mostly Caucasian women. Likewise, a variable incidence of AGT has been described during the first year postpartum in Hispanic women (between 24% and 39% in the first 6 months postpartum).26,27

The incidence of DM2 in the first year postpartum among women with AGT recorded in the present study coincides with the data found in the literature (5.4–10%).19,25 Pallardo et al., in a group of Caucasian women in Spain, observed an incidence of DM2 of 5.4% four months after delivery.19 An incidence of 9% one year after delivery was reported in a northern European Caucasian population.25 Studies in women of Hispanic origin likewise conducted in the first year after delivery27 reported a higher incidence of DM2 (17%) than in our own study and in studies involving Caucasian populations. Finally, Ko et al.29 during early postpartum in a group of Chinese women with a history of GDM, recorded an 8-fold increase in the risk of developing diabetes, based on the OGTT performed 6 weeks after delivery, vs. the group of women with normal glycemia during pregnancy.

Some ethnic groups are known to be more susceptible to diabetes than others.13 Our study reinforces the evidence linking ethnicity to the risk of suffering altered glucose metabolism after GDM. Specifically, Latin American and Central-South and East Asian women were more than 50% likely to develop AGT, vs. only 30% in the case of the Caucasian women, one year after delivery. A non-Caucasian ethnic origin has been described as a risk factor for AGT in the postpartum of women with a history of GDM in other populations. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom three months after delivery, 35% of the Indo-Asian women presented AGT, vs. 7% of the Caucasians and 5% of the African-Caribbean women (p<0.003).16 Fifteen years after delivery in a group of Australian women, Lee et al.17 found that those of Asian origin were twice as likely to suffer DM2 as Caucasian women. A recent study in California conducted 4.5 years after delivery in a large cohort of 13,000 women with GDM and 65,000 controls reported a significantly higher incidence of DM2 among Afro-American women who had developed GDM compared with Caucasian women.15 Likewise, another study conducted in the United States involving 671 Latin American women with a history of GDM recorded a 47% incidence of DM2 at 5 years postpartum.28

In accordance with previous studies in Caucasian women, our results show that the BMI before pregnancy, as a marker of insulin resistance, is predictive of AGT.18–20 In a French and Maghreb population 7 years after delivery, Vambergue et al.30 found a BMI before pregnancy of >27kg/m2 to be an independent predictor of AGT. The same results were obtained in Caucasian women 4 months and 11 years after delivery.19,20 Dalfrà et al.,18 studying Caucasian women 5 years after delivery, found the presence of obesity before pregnancy to be more common in women presenting diabetes in the postpartum period than in those with a normal glycemic index (GI) or no alterations in carbohydrate metabolism. By contrast, other authors have found no association between the pregestational BMI and carbohydrate metabolism in postpartum.25

The recurrence of GDM was also identified as a predictor of the development of DM2 or prediabetes in our study (OR=2.3). This same observation was reported by Pallardo et al.,19 who described this association in a group of Caucasian women four months after delivery.

The results of the OGTT performed during pregnancy represent another predictor of diabetes development in postpartum.4,17,19 In our study the OGTT results in pregnancy were not available, though it should be noted that women with postpartum AGT presented HbA1c values in the third trimester of pregnancy that were higher than in the women with normal glycemia, though this parameter did not reach statistical significance in the multivariate analysis. Eades et al.,31 in a study of 164 Caucasian women in the United Kingdom, found HbA1c concentration during pregnancy to be an independent predictor of DM2 8 years after delivery in women with previous GDM.

In some studies, the use of insulin in pregnancy has been described as a predictor of AGT,14,16,17,27,31 though no such association was reported by other authors.20,30 Nor was any observed in our study between insulin use and AGT. These contradictory results may be related to the fact that insulin therapy depends in part on patient preferences and on the success of lifestyle modifying interventions.

The limitations of the present study include the low percentage of patients reporting for postpartum control, though the figures are similar to those described in the literature.19 In addition, the women who reported for postpartum control had baseline characteristics that differed from those who did not attend the visit. The results obtained therefore cannot be extrapolated to the entire population of women with a history of GDM. Furthermore, we were unable to obtain data on other cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, breastfeeding, oral contraception or postpartum physical activity, which could have influenced the development of altered glucose metabolism.

ConclusionsIn a Spanish population of multiethnic origin, the incidence of alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during the first year postpartum in women with a history of GDM was 41.8%, the risk being three times greater among women of non-Caucasian origin. These findings demonstrate the need to define specific strategies for monitoring and early intervention targeted to cardiovascular risk factors in women with a history of GDM, particularly in those of non-Caucasian origin.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Prados M, Flores-Le Roux JA, Benaiges D, Llauradó G, Chillarón JJ, Paya A, et al. Incidencia y factores asociados al metabolismo alterado de la glucosa un año después del parto en una población multiétnica de mujeres con diabetes mellitus gestacional en España. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:240–246.