To validate the use of supine position and CT images for assessing abdominal circumference (AC).

MethodA prospective study in consecutive patients undergoing scheduled abdominal CT at our center between 17 and 25 September 2012.

AC was measured four times:

- 1.

Standing.

- 2.

While lying on the CT table.

- 3.

On CT images with a skin contour line, using OsiriX software.

- 4.

On CT images with an ellipse perimeter formula, using RAIM Alma 2010 software.

Measurements 1 and 2 were sequentially done by the same trained nurse before abdominal CT just above the iliac crest, while measurements 3 and 4 were done on the last abdominal CT slice not showing the iliac bone. Student's t tests and Q-Q and Bland–Altman plots were used for statistical analysis.

ResultsA total of 102 patients were recruited. Mean age, 60 (35–78) years. Mean BMI, 25 (18–39) kg/m2. Mean AC, 93.2 (73–135) cm.

No significant differences were found between the four ACs measured (Student's t test, P=0.83).

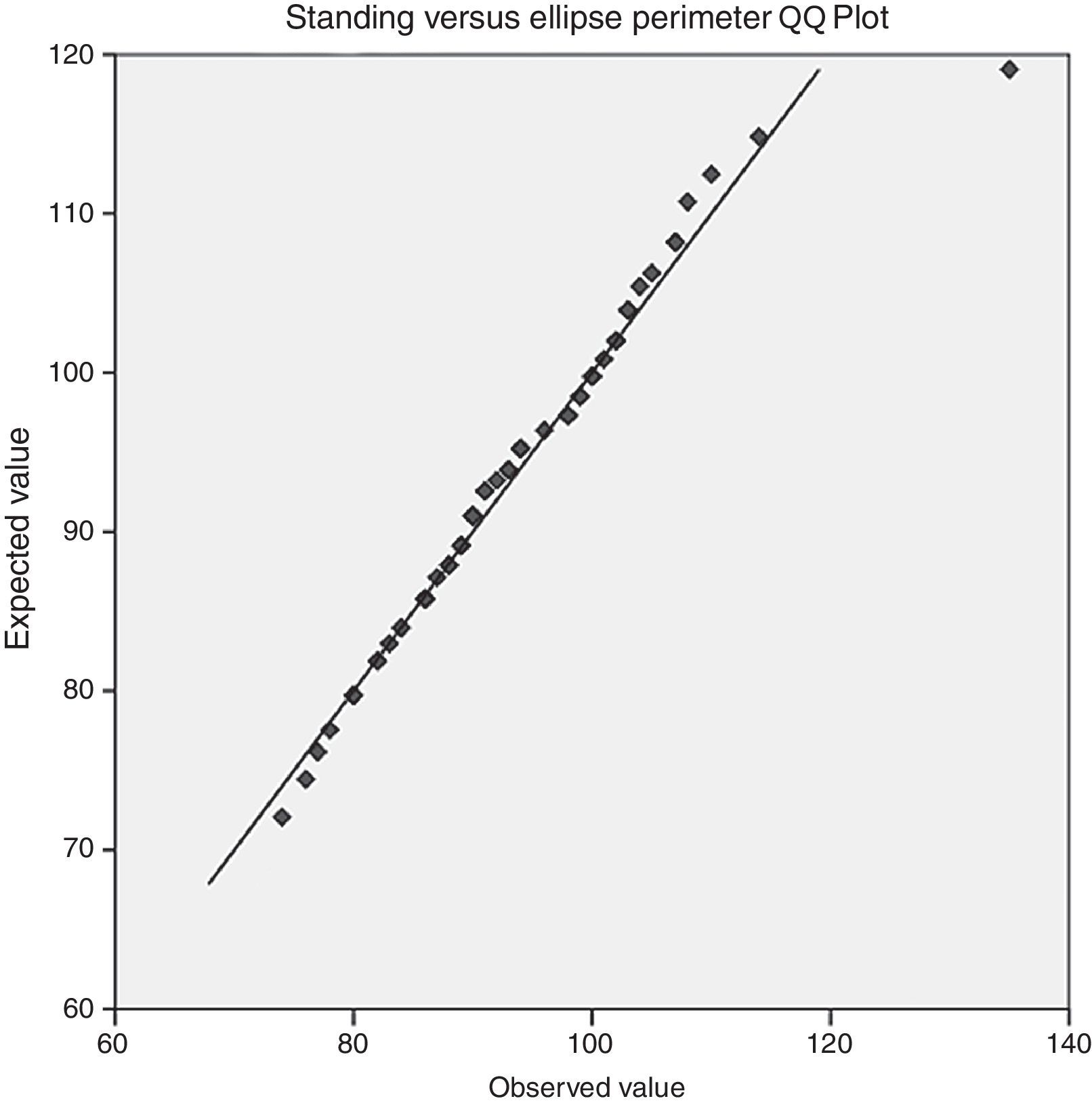

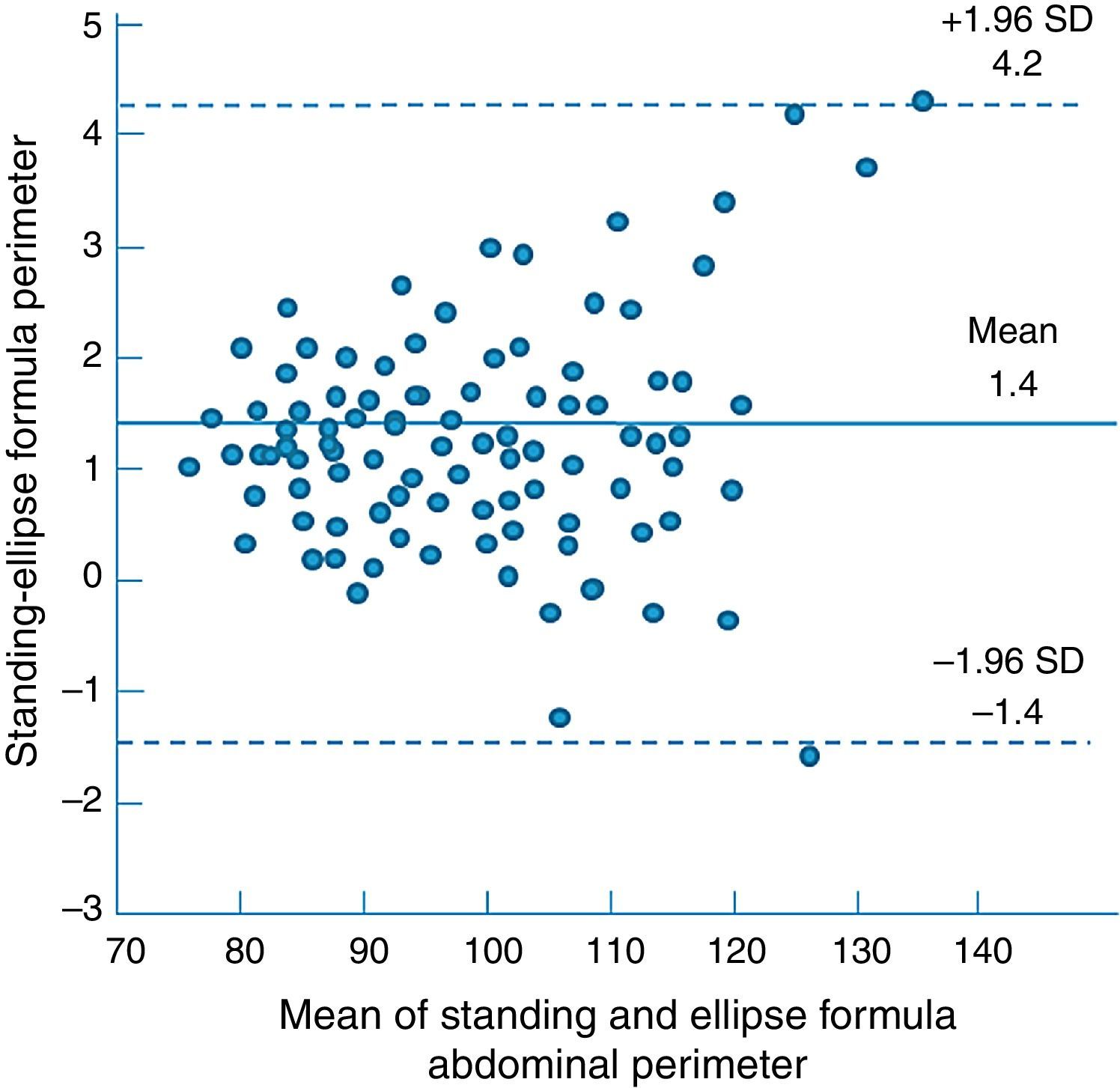

Q-Q and Bland–Altman plots showed good overlapping for the low and central values (73–110cm) with a greater scatter for extremely high values.

For the ellipse estimation, R2 was 0.987 with a mean error of 0.4cm and a stretch dispersion between 1.1 and −0.3cm.

ConclusionSupine (either measured or estimated on CT images by free hand elliptical ROI or ellipse formula) and standing measurements appear to be equivalent for abdominal circumferences <110cm.

Validar el uso de la posición supina y de imágenes de TAC para la evaluación de la circunferencia abdominal (AC).

MétodoEstudio prospectivo de pacientes consecutivos sometidos a TAC abdominal programada en nuestro centro entre el 17-25 de septiembre de 2012.

La AC se midió 4 veces:

- 1.

Bipedestación.

- 2.

Posición supina sobre la mesa de TAC.

- 3.

En imágenes de TAC con una línea siguiendo el contorno de la piel.

- 4.

En imágenes de TAC mediante la fórmula del perímetro de la elipse.

Las mediciones 1 y 2 se realizaron por el mismo enfermero de manera secuencial antes de la TAC abdominal, justo por encima de la cresta ilíaca, y las mediciones 3 y 4 en imágenes TAC, en el último corte por encima de la cresta ilíaca. Se utilizaron los test de «t» de Student, Q-Q y Bland y Altman.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 102 pacientes. La edad media fue de 60 años (35-78), el IMC medio de 25 kg/m2 (18-39), y la AC media de 93,2 cm (73-135).

No se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los 4 AC medidos («t» de Student p=0,83).

En los análisis Q-Q y Bland-Altman se encontró para las 4 mediciones un buen solapamiento de los valores bajos y centrales (73-110cm), con una mayor dispersión para los valores muy altos.

Hubo muy buena correlación entre AC en bipedestación y estimado mediante el perímetro elíptico (R=0,987), con media de error de 0,4cm y dispersión de −0,3-1,1cm.

ConclusiónLa medición de la AC en bipedestación y en decúbito supino (ya sea medida o estimada en imágenes de TAC) parece ser equivalente para perímetros abdominales <110cm.

The waist circumference is one of the criteria used for the definition of the metabolic syndrome.1 It is also an independent cardiovascular risk factor, with higher predicting value than the body mass index.2

In retrospective studies it can be difficult to obtain the value of the waist circumference if these data were not specifically measured before. Moreover, as the waist circumference changes with time, it cannot be evaluated retrospectively.

Abdominal CT images fulfill perfectly the purpose of saving a snapshot of the abdominal circumference of a person at a certain moment in time. An apparent limitation of this idea is the fact that abdominal CTs are performed in supine position and the abdominal perimeter is usually measured with the patient in standing position.3,4 Nonetheless, recent studies suggested that supine position can also be used with minimal differences.5,6

The objective of our study was to validate the use of supine position and abdominal CT images for the evaluation of waist circumference by demonstrating that the abdominal perimeter obtained from abdominal CT images is equivalent to the real-life measured waist circumference.

MethodWe performed a prospective study with three independent observers in consecutive out-patients who underwent a programmed abdominal CT in our center between the 17th and the 25th of September 2012.

The waist circumference was measured 4 times:

- 1.

In standing position.

- 2.

In supine position on the CT table.

- 3.

On CT images with a free-hand elliptical line following skin contour.

- 4.

On CT images using an ellipse perimeter formula, imputing anterior-posterior and transverse abdominal diameters.

In all patients a measurement of the abdominal circumference was performed both in standing and supine positions by the same nurse in a sequential mode, just before the abdominal CT. A Gulick type measuring tape (North Coast Medical Inc. – Gilroy, CA, USA) was used.

The algorithm for measuring the abdominal circumference was the following.4 First the abdominal region was cleared. The patients stood with the feet shoulder-width apart and the arms crossed over the chest. The iliac crest was palpated. The measuring tape was placed horizontally around the patient's abdomen, first wrapping it around the patient's legs and then moving it up, aligning the bottom edge of the tape with the upper limit of the iliac crest. The tape was gently tightened around the patient's abdomen without depressing the skin. After the patients took 2 or 3 normal breaths the abdominal circumference was measured at the end of a normal expiration.

The second measurement was performed with the patient lying down on the CT table. The waist circumference was measured in the vertical plane cranial from the iliac crest, similar to the standing measurement.

All patients underwent an abdominal CT that was indicated for diagnostic purpose. The study adheres to local regulations and standards and was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

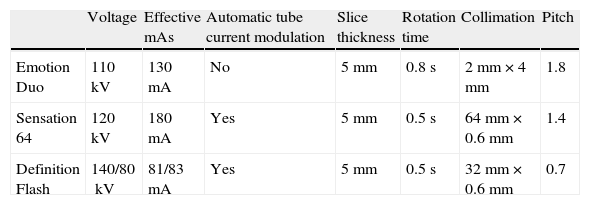

All patients underwent an abdominal CT on a Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) CT equipment (Emotion Duo, Sensation 64 or Definition Flash). The detailed CT acquisition parameters for a standard non-enhanced abdominal scan are outlined in Table 1. All examinations were performed using a 5-mm slice thickness for acquisition and reconstruction. In some patients, 1-mm slices were also obtained during the radiological procedure. Because 1-mm slices were not available in all patients, we performed the measurements using the non-enhanced 5-mm slices. The CT images were reviewed using Raim Alma 2010 (© ALMA IT SYSTEMS, Barcelona, Spain) and Osirix (Geneva, Switzerland) (http://www.osirix-viewer.com) software.

Detailed CT acquisition parameters for a standard non-enhanced abdominal scan.

| Voltage | Effective mAs | Automatic tube current modulation | Slice thickness | Rotation time | Collimation | Pitch | |

| Emotion Duo | 110kV | 130mA | No | 5mm | 0.8s | 2mm×4mm | 1.8 |

| Sensation 64 | 120kV | 180mA | Yes | 5mm | 0.5s | 64mm×0.6mm | 1.4 |

| Definition Flash | 140/80kV | 81/83mA | Yes | 5mm | 0.5s | 32mm×0.6mm | 0.7 |

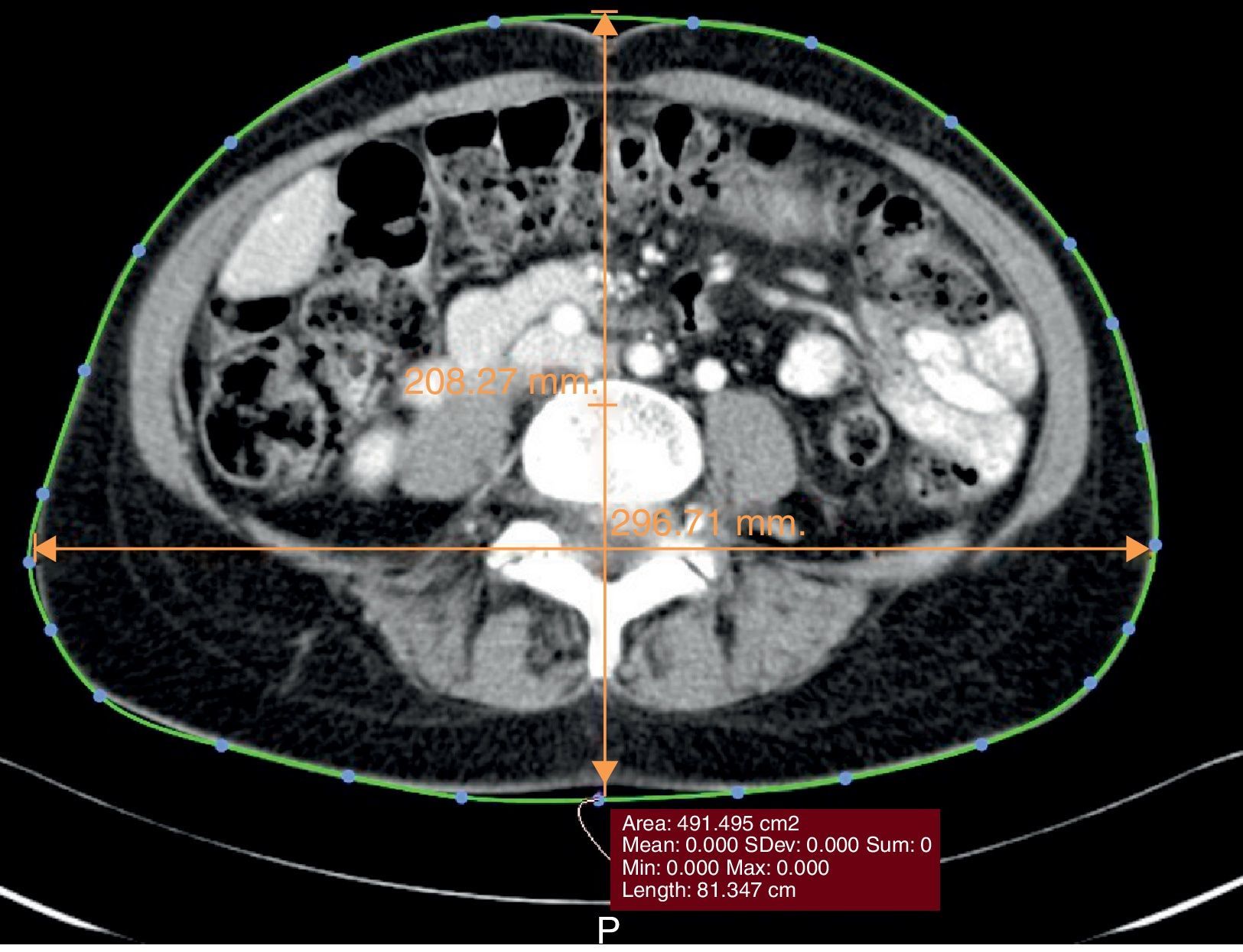

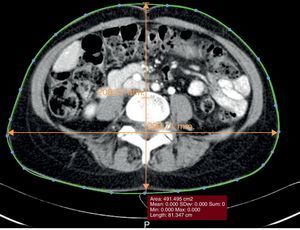

The abdominal circumference was evaluated on images right above the iliac crest, on the last slice, from cranial to caudal, not showing the iliac bone, thus imitating the algorithm used for the measurements performed in both standing and supine position.

RAIM Alma 2010 (Barcelona, Spain) was used for the evaluation of the anterior–posterior and the transverse abdominal diameter. The abdominal perimeter was estimated using the formula of the perimeter of an ellipse, “a” being the anterior–posterior diameter and “b” being the transverse diameter:

OsiriX (Geneva, Switzerland) DICOM software was used to measure the abdominal perimeter using a free-hand elliptical ROI following the skin contour, mimicking the use of a measuring tape (Fig. 1).

The measurements and estimations done in the cross-sectional images were performed blinded to the real waist circumference. The observers using the RAIM ALMA and the Osirix software were independent and blinded to each other's evaluations.

Measurements are expressed as mean±standard deviation and range.

Data were collected and analyzed using Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) and SPSS 15 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student t, Pearson correlation, Q-Q plot, and the Bland–Altman analysis were used. P values inferior to 0.05 were considered significant from a statistical point of view. For the Bland–Altman plot evaluating two different methods of performing the measurements, we considered that if the differences within the limits of agreement (LOA)=“mean±1.96 standard deviation” are not clinically important, the two methods may be used interchangeably.

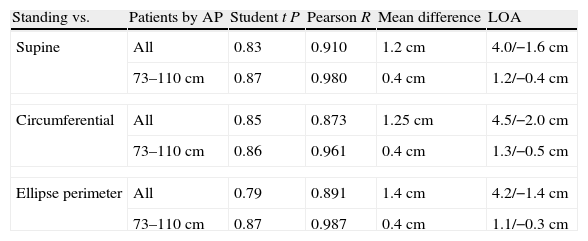

ResultsThe study was proposed to 105 patients. Three patients declined to participate. A total of 102 patients were included. The mean age was 60±14 years (range 32–75), the percentage of women was 36%. The mean BMI was 25±7.2 (range 18–39), 25.9±7.4 (18–35) for women and 24.4±6.8 (19–39) for men. The mean waist circumference was 93.2cm±10.9 (range 73–135), 91.2±9.8 (73–118) for women and 94.3±11.2 (75–135) for men. The reason why patients underwent abdominal CT was: in 23 patients stone disease, in 37 patients abdominal pain, in 10 patients benign abdominal conditions follow up, in 17 patients benign abdominal surgery follow-up (>6 month since surgery), in 15 patients abdominal tumor surgery follow-up (>6 month since surgery). The results of the standing measurement compared with the supine one, the circumferential estimation on CT images and the ellipse perimeter estimation also on CT images can be found in Table 2.

Results of the comparison of standing abdominal perimeter versus supine, circumferential and ellipse perimeter abdominal perimeter.

| Standing vs. | Patients by AP | Student t P | Pearson R | Mean difference | LOA |

| Supine | All | 0.83 | 0.910 | 1.2cm | 4.0/−1.6cm |

| 73–110cm | 0.87 | 0.980 | 0.4cm | 1.2/−0.4cm | |

| Circumferential | All | 0.85 | 0.873 | 1.25cm | 4.5/−2.0cm |

| 73–110cm | 0.86 | 0.961 | 0.4cm | 1.3/−0.5cm | |

| Ellipse perimeter | All | 0.79 | 0.891 | 1.4cm | 4.2/−1.4cm |

| 73–110cm | 0.87 | 0.987 | 0.4cm | 1.1/−0.3cm | |

AP=abdominal perimeter; LOA=limits of agreement.

There was a good correlation between standing, supine, circumferential and ellipse perimeter waist circumference (see Table 2 for R values). The Student t test showed there were no significant differences between the four measurements (statistical results are also shown in Table 2).

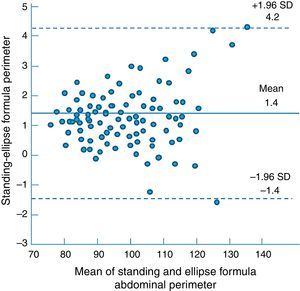

The Q-Q plot showed good overlapping for inferior and central values with some dispersion of extreme superior values. The Bland–Altman analysis showed a mean difference of 1.2cm between standing and supine measurements, 1.2cm between standing and circumferential CT measurements and finally 1.4cm between standing and ellipse formula CT evaluation measurements (complete results can be found in Table 2). A subanalysis of low and central values (73–110cm) showed much lower mean differences – 0.4cm for each of supine, circumferential and ellipse formula AP when compared to standing AP. Q-Q dispersion plot and a Bland–Altman analysis graph of standing versus ellipse perimeter waist circumference can be found in Figs. 2 and 3. As both Q-Q plot and Bland–Altman analyses practically compare the measurement values of the same patient, the good results of both the Q-Q plot and the Bland Altman analysis maintained when subanalysing men and women subgroups. The cut points that defined a higher dispersion of values were 109cm in women and 110cm in men.

DiscussionThe abdominal perimeter is an increasingly used parameter to evaluate cardiovascular risk,7 the presence of metabolic syndrome8 or the nutritional status.5 The use of an abdominal perimeter measured in supine position can be justified in patients with important disabilities in which an evaluation of the nutritional status is important.5 Nonetheless the possibility of measuring the waist circumference in supine position, with results similar to standing position, opens the door to measuring it in supine position from CT images. Furthermore, the CT images are saved and archived which allows them to be used any time an evaluation of the abdominal perimeter is required at a specific moment in time.

Previous studies evaluated the possibility of measuring the waist circumference in supine position.5,6 The result was a good correlation between the standing and the supine perimeter. Nonetheless the two circumferences were not identical so the authors identified a formula that could help to easily calculate the standing perimeter from the supine one.5 One possible limitation of this study is that the authors chose the measuring method for abdominal perimeter described in the WHO guidelines,3 with measurements performed at half-distance between the iliac crest and the 12th rib.

In our study the measurements were performed according to the NIH Practical Guide to Obesity guidelines,4 at the level of the iliac crest. Because of the presence of hard bony landmarks, the abdominal perimeter measured at this level is less likely to variate between standing and supine position. As both measuring methods are approved for the evaluation of AP in standing position, the logical choice for the validation of a supine measurement equivalent to the standing one is that which results less prone to changes according with body position. In our study only patients with very high abdominal diameters showed a variation.

The reason why patients underwent an abdominal CT were not considered relevant in relation with the comparison between standing and supine AP. Liquid accumulating diseases were irrelevant as all measurements were performed in a 5min time interval; therefore there was no material time to change tissue composition. No patients had diseases related to a possible loss of muscle tone; anyway, the fact that measurements were performed over the bony landmark of the iliac crest would have diminished the effect of a lower muscle tone.

From a statistical point of view any two methods that are designed to measure the same parameter should have good correlation when a set of samples are chosen such that the property to be determined varies considerably. A high correlation does not automatically imply that there is good agreement between the two methods. For that reason we decided to perform a Bland–Altman analysis to determine the mean error between various ways of measuring the abdominal perimeter, and to evaluate if any of these alternative methods could have clinical applicability.

In our study we found that waist circumference yields similar results in standing and supine position, with a mean difference of only 1.2cm. The Bland–Altman analysis demonstrates that the dispersion of the mean error is not very wide, between 4.0 and −1.9cm, at the expense of extreme values. From a clinical point of view this means that for the low and central values (perimeters between 73 and 110cm) the overlapping of the results of the two techniques is almost perfect, with no clinical differences. Differences may only occur with very large abdominal perimeters. Nonetheless, this does not change the clinical significance of the measurement as the important cut-points for the abdominal perimeter are either 80 and 94cm1 or 88 and 102cm,9 depending on which guidelines are used.

The radiological estimation of the abdominal perimeter by a circumferential line or by using the ellipse perimeter formula also seems to function as an equivalent of the standing waist circumference. Both methods yielded similar results. The measurement performed by using a circumferential line that approximates the use of a Gulick tape seems more logical to use in this case. Furthermore, the results were practically identical to those obtained by direct measurement of the abdominal perimeter in supine position. Nonetheless, this feature was only available in a program, OsiriX, which we do not use on regular bases. Our workstations are still based on Windows and the RAIM Alma 2010 program does not allow a direct estimation of any kind of perimeter.

For that purpose we introduced the idea of approximating the abdominal circumference by using a formula proposed for the estimation of the perimeter of an ellipse. As expected, we found a good correlation between the measurements, and the Bland–Altman analysis returned a mean error of just 1.4cm. As in the case of the supine abdominal perimeter, the differences appeared with very high values, (more than 110). The central and low values of the waist circumference overlapped almost perfectly (Figure 2). The sub-analysis of values between 73 and 110cm showed a mean error of 0.4cm, with dispersion between 1.1 and −0.3cm, which are not relevant in practical terms.

ConclusionOur study showed that for abdominal perimeters of less than 110cm the supine and standing position measurements are equivalent. The estimation of the abdominal perimeter using either a circumferential line or the formula for the perimeter of an ellipse is also equivalent to the real abdominal perimeter measured in standing position.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with the manuscript.