Pneumonia with a mild prolonged course is the most frequent clinical presentation of the lower respiratory tract infection by Chlamydia pneumoniae.1 However, severe, life-threatening pneumonia has been reported, mainly in elderly hosts and those with chronic-associated conditions, but in previously healthy patients as well.1–5 Acute Fibrinous and Organizing Pneumonia (AFOP) is a histologic pattern associated with a clinical picture of acute lung injury which differs from the classic presentations of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), and eosinophilic pneumonia (EP).1 Like these patterns, however, AFOP can occur in an idiopathic setting or in association with a wide spectrum of clinical conditions.6 The dominant histological finding in AFOP is the presence of intra-alveolar fibrin in the form of “fibrin balls” within the alveolar spaces.6 AFOP has a poor prognosis, with an overall mortality rate of about 50%.6

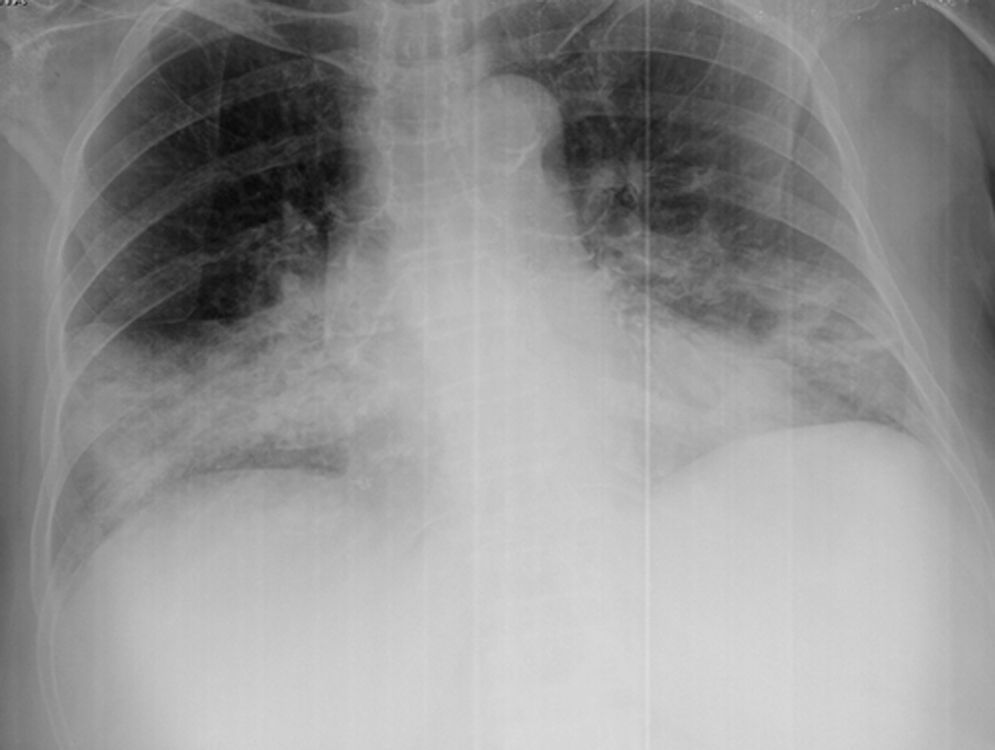

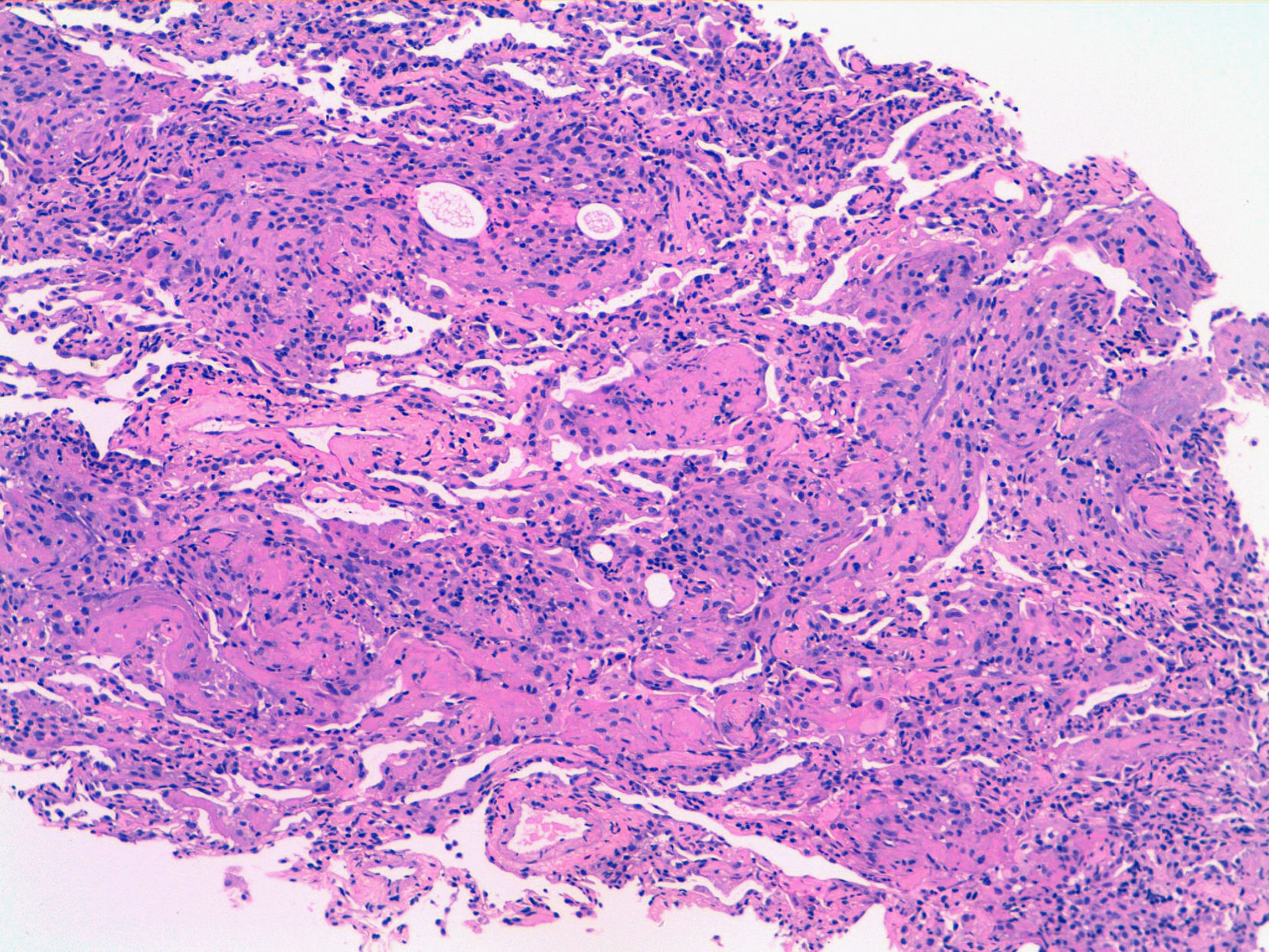

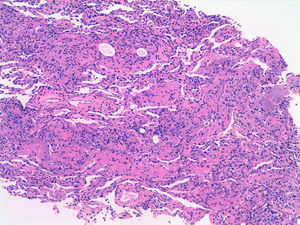

Here we present a case of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection associated with AFOP, respiratory failure, multi-organ dysfunction, and death. A 69-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus and chronic liver disease consulted for a four-day history of arthromyalgias, rhinorrhea, dry cough, fever, and progressive shortness of breath. She reported no relevant epidemiological history, such as exotic travel or contact with animals. She had received the influenza vaccine annually and pneumococcal vaccine the previous year. Her usual treatment was an ACE inhibitor and glibenclamide. At hospital admission, she was tachypneic (32 breathsmin−1); oxygen saturation was 92% breathing room air, blood pressure 120/60mmHg, pulse 111 beatsmin−1, and axillary temperature 37.9°C. Respiratory auscultation revealed crackles in both lower hemithoraces. Room air arterial blood gas determination showed acute respiratory hypoxia with an arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) of 8.3kPa (62mmHg), and arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2) of 2.7kPa (20mmHg), a pH of 7.5, and oxygen saturation of 95.4%. Other notable laboratory findings were platelet count 34,000 cellsmm−3 (34.0 cells × 109·L−1), white blood cell count 3,900 cellsmm−3 (3.9 cells × 109·L−1) with 87% neutrophils, and Na+ 129 mmolL−1. Chest radiography revealed an alveolar consolidation in the right-middle and right-lower lobes and the lingula (Fig. 1). A sputum sample could not be obtained for examination. Urinary antigen detection by immunochromatography was negative for both Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae. With the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, the patient was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (1g/day) and levofloxacin (500mg/day) for 24hours, followed by levofloxacin after establishing that urinary antigen for S. pneumoniae was negative. During the following two days, the patient's clinical condition deteriorated; consolidation on chest radiograph progressed and respiratory failure ensued, requiring transfer to the intensive care unit, invasive mechanical ventilation, and systemic corticosteroids. A chest computed tomographic scan showed areas of consolidation and ground glass opacities in the lower lobes. Studies for mycobacteria, fungi, conventional bacterial culture and viral cultures (Adenovirus, Influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Herpes simplex 1/2, Cytomegalovirus and Varicella Zoster) from a bronchoalveolar lavage were negative. Transbronchial biopsy showed an inflammatory process with a predominance of alveolar fibrin exudate in the form of “fibrin balls” without formation of hyaline membranes, and signs of organization compatible with AFOP (Fig. 2). Immunology was negative for vasculitis (anti-proteinase 3, anti-myeloperoxidase, and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies), and an echocardiography showed good global contractility and a pulmonary artery pressure of 4.9kPa (37mmHg). In spite of high doses of corticosteroids, respiratory distress and multiorgan dysfunction ensued and the patient died after 20 days of admission. Autopsy was not performed because it was not authorized by the family.

Serologies for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetti and Legionella pneumophila were negative. Chlamydia pneumoniae serology anti-IgG, using indirect microimmunofluorescence techniques (MIF, Focus Diagnostics) and Enzyme immunoassay (EIA, Savyon Diagnostics), showed a four-fold rise in IgG titers (1:32-1:512) between the first and second serum samples extracted 13 days apart. IgM detection was inconclusive by EIA.

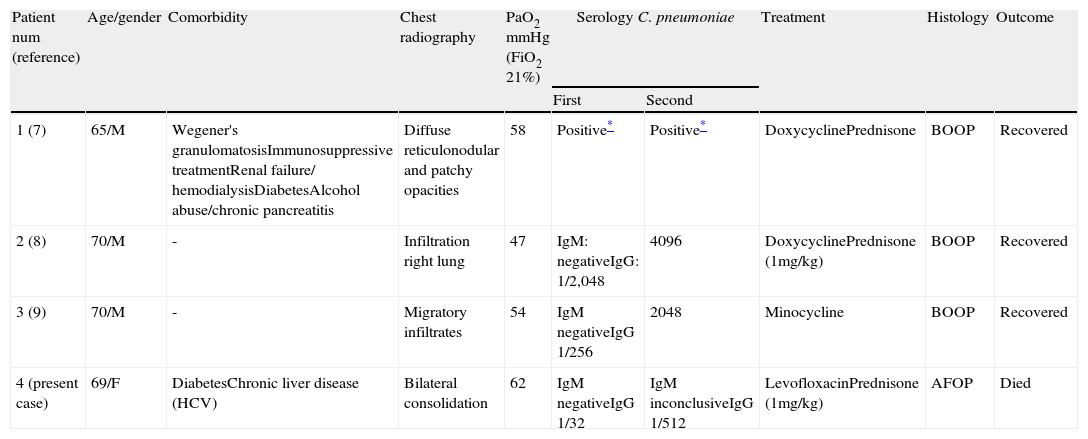

Severe respiratory infection by C. pneumoniae occasionally has been associated with histological features of BOOP, which appeared to be secondary to the pulmonary infection.7-9 However, to our knowledge, no cases of C. pneumoniae infection associated with AFOP have been reported to date. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the four cases of C. pneumoniae infection associated with BOOP reported in the literature, and the present case, associated with AFOP. All four patients were around the seventh decade of life: two of them had associated comorbidities and the other two were previously healthy. Chest radiographic findings differed slightly in the four cases, but alveolar infiltrates were always present. Three patients were treated with prednisone at doses 1mg/kg, in combination with an appropriate antimicrobial agent. All of them developed respiratory failure. The subsequent course was satisfactory under treatment in the three cases with BOOP. Despite appropriate antibiotic treatment and steroids, the clinical course of our patient was unsatisfactory and she died of respiratory failure. Treatment with steroids is almost always successful in BOOP, but are frequently less effective in AFOP due to the presence of fibrin in the alveolar spaces.10,11

Main characteristics of the four cases of C. pneumoniae infection associated with either BOOP or AFOP.

| Patient num (reference) | Age/gender | Comorbidity | Chest radiography | PaO2 mmHg (FiO2 21%) | Serology C. pneumoniae | Treatment | Histology | Outcome | |

| First | Second | ||||||||

| 1 (7) | 65/M | Wegener's granulomatosisImmunosuppressive treatmentRenal failure/ hemodialysisDiabetesAlcohol abuse/chronic pancreatitis | Diffuse reticulonodular and patchy opacities | 58 | Positive* | Positive* | DoxycyclinePrednisone | BOOP | Recovered |

| 2 (8) | 70/M | - | Infiltration right lung | 47 | IgM: negativeIgG: 1/2,048 | 4096 | DoxycyclinePrednisone (1mg/kg) | BOOP | Recovered |

| 3 (9) | 70/M | - | Migratory infiltrates | 54 | IgM negativeIgG 1/256 | 2048 | Minocycline | BOOP | Recovered |

| 4 (present case) | 69/F | DiabetesChronic liver disease (HCV) | Bilateral consolidation | 62 | IgM negativeIgG 1/32 | IgM inconclusiveIgG 1/512 | LevofloxacinPrednisone (1mg/kg) | AFOP | Died |

BOOP: Bronchiolitis Obliterans with Organizing Pneumonia; AFOP: Acute Fibrinous and Organizing Pneumonia.

The case presented here illustrates that C. pneumoniae-associated AFOP should be considered in cases of atypical pneumonia with an unfavorable clinical evolution and that appropriate serological tests should be part of the etiological search in cases of BOOP or AFOP of unknown origin.