We present a case of endophthalmitis caused by Phialophora verrucosa and review the available literature on Phialophora ocular infections.

A 66-year-old man with hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus and bilateral chronic glaucoma consulted the Ophthalmology Department about his red right eye. The patient did not report any previous eye surgery or recent ocular trauma. Episcleritis was diagnosed and he was started on topical corticosteroids and antibiotics. Six months later, he complained about loss of vision, and ophthalmic examination showed a fine brown material in the anterior chamber. Material aspirate and aqueous tumor were sent to the Microbiology and Pathology laboratories. Histological examination showed septate hyphae and fungal spores. After a week on Sabouraud dextrose agar, the material from both samples became black, embedded in the medium, and increased its size. On potato dextrose agar, the colony was initially white and turned to black with a black reverse. Microscopically, hyphae were septate, brown and branched, phialides were flask shaped with a cup-like collarette and ellipsoidal conidia accumulated at the apice of the phialide. All characteristics corresponded to the Phialophora genus. The strain was sent to a reference laboratory where it was identified as P. verrucosa by morphological criteria and PCR and sequencing using ITS1 and ITS4 primers, and antifungal susceptibility testing was made according to EUCAST methodology. A MIC less than or equal to 0.5mg/L was obtained for amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole and caspofungin. The patient was started on oral voriconazole (200mg every 12h), amphotericin B eye drops (every 6h) and topical corticosteroid, with no improvement. Vitrectomy and intravitreal amphotericin B injection (5μg) were performed twice and new samples were taken. Finally, the patient underwent enucleation of the eye due to recurrent pain and blindness. Currently, he is asymptomatic.

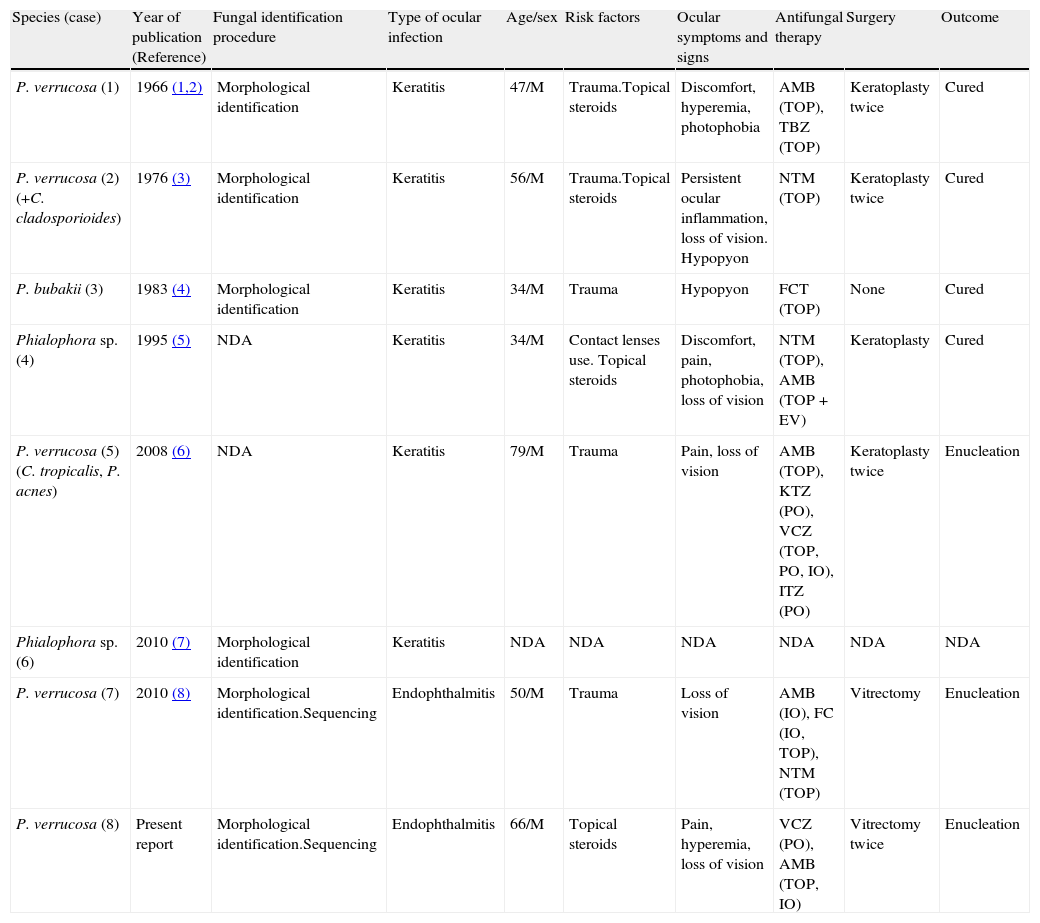

There are seven reported cases of ocular infections caused by Phialophora species1–8 (Table 1). Data were not available for one patient. All the remaining patients were men, with a mean age of 52.3 years. The most frequent risk factors were trauma, occurred between days and months before the first ophthalmologic consultation, and treatment with topical corticosteroids. In our case, the patient reported a trauma with a piece of wood thirty five years before, with recurrent episodes of hyperemia during the last few years. As regards the clinical presentation of the infection, six patients had keratitis, and two had endophthalmitis. All patients were initially treated with topical and/or oral antifungals, most of them unsuccessfully. Surgery was required in six patients, keratoplasty in four and vitrectomy in two, followed by intraocular and/or intravenous antifungal therapy in four of them. More than one antifungal agent was used in five cases, and amphotericin B was the most commonly prescribed drug. Due to clinical progression of the infection, the eye was enucleated in three cases. The outcome of the rest of patients was good.

Ocular infections caused by Phialophora spp. including the present case.

| Species (case) | Year of publication (Reference) | Fungal identification procedure | Type of ocular infection | Age/sex | Risk factors | Ocular symptoms and signs | Antifungal therapy | Surgery | Outcome |

| P. verrucosa (1) | 1966 (1,2) | Morphological identification | Keratitis | 47/M | Trauma.Topical steroids | Discomfort, hyperemia, photophobia | AMB (TOP), TBZ (TOP) | Keratoplasty twice | Cured |

| P. verrucosa (2) (+C. cladosporioides) | 1976 (3) | Morphological identification | Keratitis | 56/M | Trauma.Topical steroids | Persistent ocular inflammation, loss of vision. Hypopyon | NTM (TOP) | Keratoplasty twice | Cured |

| P. bubakii (3) | 1983 (4) | Morphological identification | Keratitis | 34/M | Trauma | Hypopyon | FCT (TOP) | None | Cured |

| Phialophora sp. (4) | 1995 (5) | NDA | Keratitis | 34/M | Contact lenses use. Topical steroids | Discomfort, pain, photophobia, loss of vision | NTM (TOP), AMB (TOP+EV) | Keratoplasty | Cured |

| P. verrucosa (5) (C. tropicalis, P. acnes) | 2008 (6) | NDA | Keratitis | 79/M | Trauma | Pain, loss of vision | AMB (TOP), KTZ (PO), VCZ (TOP, PO, IO), ITZ (PO) | Keratoplasty twice | Enucleation |

| Phialophora sp. (6) | 2010 (7) | Morphological identification | Keratitis | NDA | NDA | NDA | NDA | NDA | NDA |

| P. verrucosa (7) | 2010 (8) | Morphological identification.Sequencing | Endophthalmitis | 50/M | Trauma | Loss of vision | AMB (IO), FC (IO, TOP), NTM (TOP) | Vitrectomy | Enucleation |

| P. verrucosa (8) | Present report | Morphological identification.Sequencing | Endophthalmitis | 66/M | Topical steroids | Pain, hyperemia, loss of vision | VCZ (PO), AMB (TOP, IO) | Vitrectomy twice | Enucleation |

AMB: amphotericin B; EV: endovenous; FC: fluconazole; FCT: flucytosine; IO: intraocular; ITZ: itraconazole; KTZ: ketoconazole; NDA: no data available; NTM: natamycin; PO: by mouth; TOP: topical; TBZ: thiabendazole; VCZ: voriconazole.

Fungal infections of the eye are mainly caused by Candida, Fusarium and Aspergillus species. Genus Phialophora, a dematiaceous fungus, is a rare agent of ocular infection; in fact, we have only found seven reported cases. Ocular trauma was the most common predisposing factor. In our patient, due to the long time passed since the trauma, we cannot assume it as the origin of the infection. More than half of the patients received corticosteroids that could facilitate the fungal infection and its progress. To reach the diagnosis of ocular fungal infections, a collection of appropriate specimens is mandatory: in keratitis, superficial scrapings or a corneal biopsy, and in endophthalmitis, aqueous and vitreous aspirates. A direct microscopic examination offers a rapid presumptive diagnosis and culture is essential to identify the fungus involved, and to determine the susceptibility profile of the strain. Since dematiaceous fungi are commonly found in the environment, their clinical significance needs to be assessed. In our case, histological examination and repeated cultures from several intraocular samples obtained at different times confirmed that P. verrucosa was the causative agent. Despite the lack of interpretative MIC breakpoints and limited correlation between MIC and treatment outcome, antifungal susceptibility testing is recommended, especially when the fungus is infrequently isolated. Phialophora is usually susceptible to amphotericin, itraconazole and voriconazole.9 In the management of aspergillus keratitis, the prompt initiation of antifungal therapy and surgery in refractory patients is recommended, and vitrectomy followed by intravitreal amphotericin B or intravitreal or systemic voriconazole in aspergillus endophthalmitis.10 Currently, there are no therapeutic recommendations for ocular infections caused by fungi other than Aspergillus.

In summary, although Phialophora is rarely involved in eye infections, its role as a potential pathogen should be kept in mind when it is isolated from ocular samples. Given the availability of antifungals, susceptibility testing of the strain is important to select the optimal therapy.

We thank Dr. Calixto Arias for his assistance in editing the manuscript. We also thank the Servicio de Micología, Centro Nacional de Microbiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, for the identification of the species and antifungal susceptibility of the strain.