The incidence of Campylobacter coli has increased and with greater resistance to antibiotics than Campylobacter jejuni.

ObjectivesTo determine the epidemiology distribution of Campylobacter spp. in our health area, and the sensitivity to commonly tested antibiotics.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive study of cases of campylobacteriosis (2016–2020) recovered from stool cultures as laboratory routine protocol. Sensitivity was tested following EUCAST recommendations.

ResultsOf 1319 campylobacteriosis (C. jejuni 87.7%, C. coli 12.3%) we found a decrease in C. jejuni cases in 2019, and an increase in C. coli. Statistically significant differences were seen in age and gender distribution. The resistance percentages have generally decreased, with higher percentages of resistance in C. coli than in C. jejuni, being significant for erythromycin.

ConclusionsThere is not an increase of C. jejuni and its resistance but there is a not alarming increase of incidence of C. coli and its resistance in our health area.

La incidencia de Campylobacter coli ha aumentado y con mayor resistencia a los antibióticos que Campylobacter jejuni.

ObjetivosDeterminar la distribución epidemiológica de Campylobacter spp. en nuestra área de salud y la sensibilidad a los antibióticos comúnmente probados.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de casos de campilobacteriosis (2016-2020) recuperados de coprocultivos con el protocolo de rutina del laboratorio. La sensibilidad se probó siguiendo las recomendaciones de EUCAST.

ResultadosDe 1.319 campilobacteriosis (C. jejuni 87,7%, C. coli 12,3%) se encontró una disminución en los casos de C. jejuni en 2019, y un aumento en C. coli. Se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la distribución de edad y género. Los porcentajes de resistencia han disminuido en general, con porcentajes más altos de resistencia en C. coli que en C. jejuni, siendo significativos para la eritromicina.

ConclusionesNo hay un aumento de C. jejuni ni de su resistencia, pero sí un aumento no alarmante de la incidencia de C. coli y su resistencia en nuestra área de salud.

Campylobacter spp. is a microaerophilic gram-negative curved bacillus with corkscrew mobility due to a polar flagellum. It is responsible in humans for a zoonosis, campylobacteriosis, are poultry, wild and domestic pets its main reservoir.

The most frequent clinical manifestation is a gastrointestinal syndrome, related to the consumption of contaminated water, unpasteurized dairy products or the consumption of undercoated birds, there are also cases of campylobacteriosis related to environmental exposure or contact with farm animals.1

The incidence and prevalence of enteritis caused by of Campylobacter spp. has been increasing in the last 10 years, both in developed and developing countries, becoming the most frequent enteritis, both in adults and children,2 even higher than other recognized pathogens such as Shigella spp., Salmonella spp. or toxigenic strains of Escherichia coli.3

Being responsible for around 2.5 million cases/year of gastroenteritis in the USA alone4 and sixteen million cases of gastroenteritis worldwide.

The dramatic increase in North America, Europe and Australia is alarming, and data from regions of Africa, Asia and the Middle East indicate that campylobacteriosis is endemic in these areas, especially in children.5

The species most frequently associated with gastrointestinal pathology are firstly C. jejuni followed by C. coli (causing around 10%).4

This increase has been favoured possibly by the greater clinical awareness of its pathogenicity and by the introduction into clinical practice first by selective culture media that facilitate its isolation and later by the use of molecular techniques, especially syndromic diagnostic panels.3

Regarding clinical symptomatology, campylobacteriosis is usually mild it presents with moderate clinical symptoms and resolves spontaneously treated by supportive measures without the need of antibiotic therapy, however, diarrhoea symptoms, fever, abdominal pain and nausea can become severe6 especially in immunocompromised patients, extreme ages patients or pregnant women, in these cases antibiotic treatment is usually necessary7 The sequelae it can cause, such as Guillain–Barre syndrome or reactive arthritis, could cause serious long-term consequences.4

The resistance of Campylobacter species to antimicrobials has been documented worldwide as a result of the widespread use of antimicrobial agents in both human and veterinary practices, showing resistance to ciprofloxacin (between 60 and 80%), tetracyclines (about 40%), ampicillin (about 20%) or erythromycin (about 10% even reaching 60% in case of C. coli).8,9

Multiresistance rate of 30% has been documented, considered as such, resistant to 3 or more drugs of different groups.9

The aim of this study was to recognize the epidemiology distribution of C. jejuni and C. coli in our health area (from 2016 to 2020) according to the sex and gender of patients, and their seasonal time course, as well as to determine the sensitivity to commonly tested antibiotics.

Material and methodsRetrospective descriptive study, through the laboratory information system (LIS), of isolates of Capmpylobacter spp. in stool between 2016 and 2020 in the Microbiology Department of the University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, that serves a total of 313.040 census population. The protocol for these isolates included culture in Campylobacter selective agar plates (CCDA selective medium, Thermo Fisher Diagnostics, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) at 37°C incubation in microaerophilic condition for 48hours. Sensitivity to erythromycin 15μg (ERY), ciprofloxacin 5μg (CIP) and tetracycline 30μg (TET) was performed using Disc diffusion susceptibility testing by Kirby Bauer method for antimicrobial applying EUCAST clinical breakpoints-bacteria (v 9.0) 2019. Identification was performed with MALDI-TOF system (Vitek-MS®, BioMerieux). The statistical analysis was performed by X2 and ANOVA statistical test with SPSS program.

The statistical analysis by age, patients under 16 years old were considered children. The seasonality analysis was done by grouping the months by seasons (spring, summer, autumn and winter) and also grouping the same months of each year comparing each month with the remaining months, for the post hoc exam we used Tukey range test.

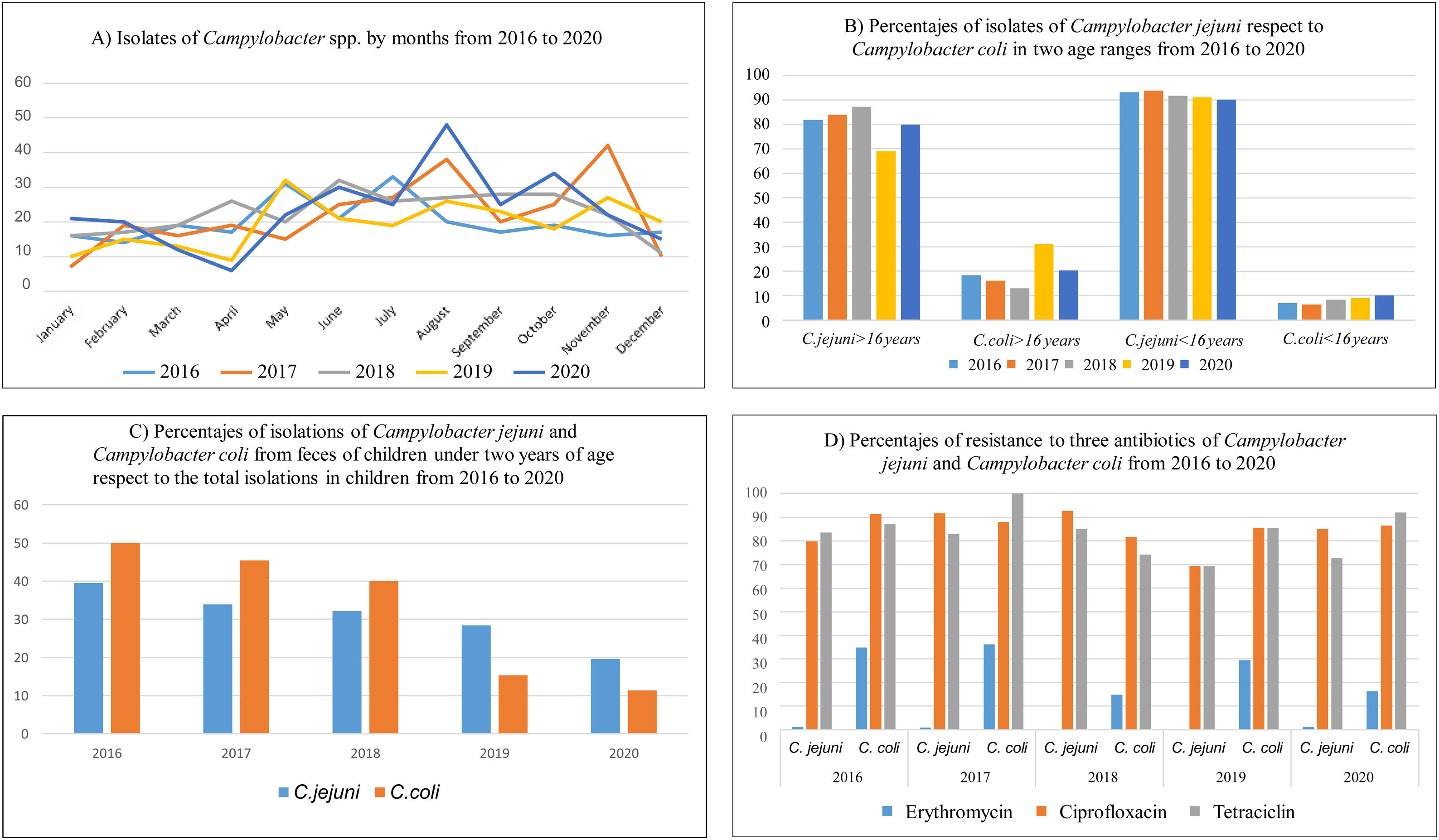

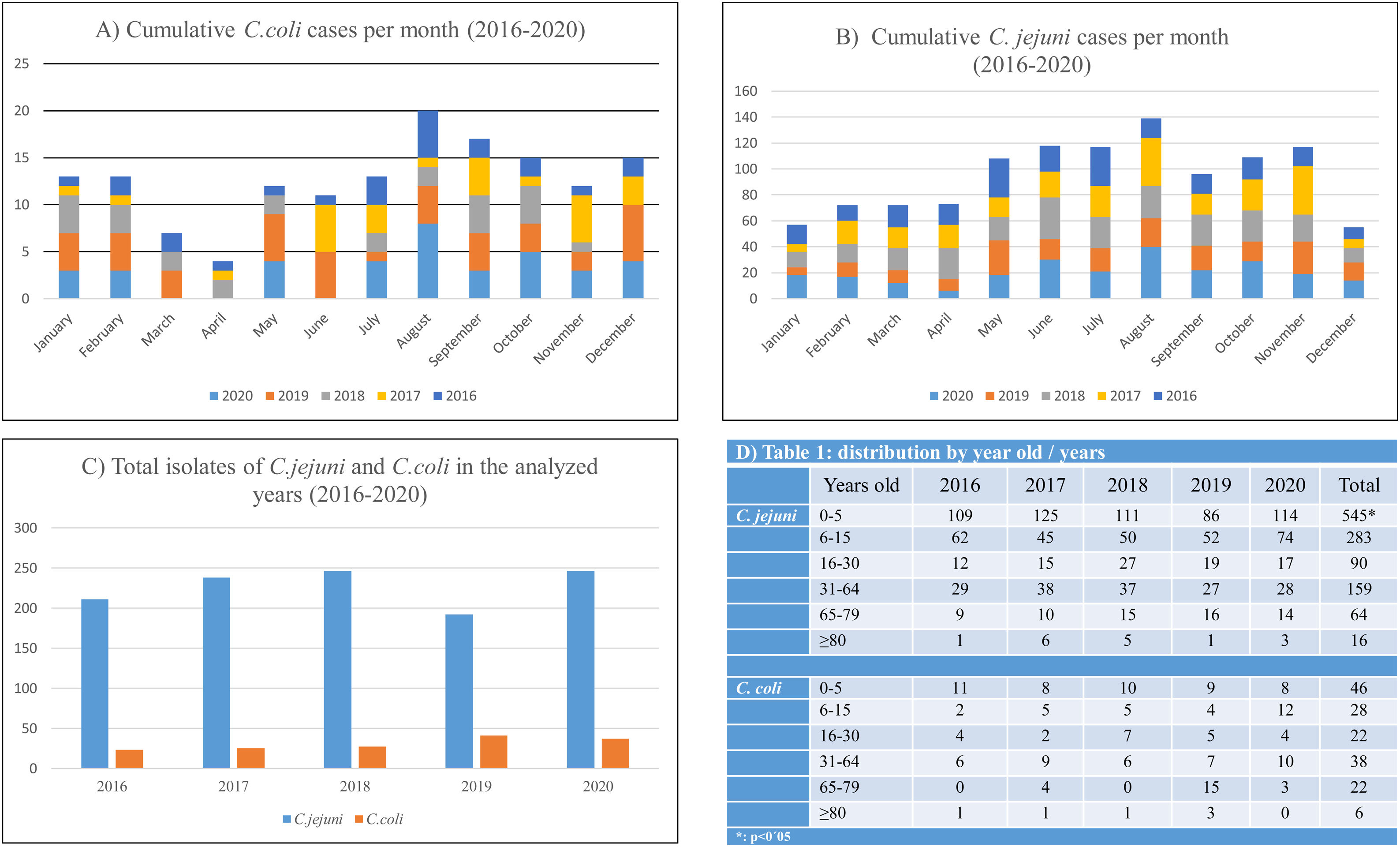

ResultsA total of 1319 campylobacteriosis were analyzed, 3.9% of the total stool cultures and 57.8% of the positive for all the enteropathogenic bacteria, isolating themselves: C. jejuni 1157 (87.7%) and C. coli 162 (12.3%). Campylobacter spp. was the first enteropathogen isolated in our area, far ahead of other genera such as Salmonella enterica (25.2%), Aeromonas spp. (15.2%), Yersinia enterocolitica (1.3%) or Shigella spp. (0.5%). We found a small decrease in C. jejuni cases in 2019, an increase in C. coli and only in adults (Figs. 1B and 2C). In our study, it was observed in a global way that the cases of Campylobacter spp increased every year, especially in August, in a more detailed study we found that we did not find statistically significant differences due to seasonality in the case of C. coli, being the practically homogeneous cases throughout the year. But if differences were found in C. jejunii, being more frequent in the summer and autumn seasons, especially in August and November, they are the months with the most associated cases and this difference is significant (Fig. 2A and B).

Statistically significant differences were seen in age being C. jejuni more frequent in paediatric age (p<0.01), especially in the first five years of life (Fig. 2D), with regard to gender distribution of campylobacteriosis was more common in men (p=0.02).

On the other hand, in our study, the most frequent clinical manifestations regardless of age were: diarrhoea in 445 (55.5%) cases, acute gastroenteritis in 210 (26.2%) cases, and bloody diarrhoea in 69 (8.6%) cases. Of all of them, it was associated with C. jejuni respectively in 377, 194 and 66 of the cases, as occurs in the study of Linde Nielsen H. et al.10

The majority isolation in both age groups remains C. jejuni, but in adults the percentage of C. coli isolates is higher than in children, 19.75% in adults compared to 8.13% in children (Fig. 1B). The rates of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates in children under 2 years of age have declined from the total number of isolates in the age range under 16 years. The percentage of C. coli isolates in children under two years of age compared to the total number of isolates in children is reversed and decreases from 50% in 2016, more than 39.5% of C. jejuni, to 11.4% in 2020, less than 19.6% of C. jejuni (Fig. 1C).

In general, in our area the antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter spp. strains has remained constant with an average in the last five years of 3.6% for erythromycin, 87.6% for ciprofloxacin and 79.8% for tetracycline, similar to other series in Spain,11 with the percentages of resistance in C coli larger than in C. jejuni, and significant for erythromycin (p=0.03).

If we do this calculation for C. coli and C. jejuni separately, resistance increases in C. coli, being 0.6%, 87.8% and 78.8% in C. jejuni and 25.4%, 86.3% and 87.6.

DiscussionWe do not demonstrate seasonality for C. coli but do so for C. jejuni as other authors do12 perhaps because we have studied five years only, despite which the relationship with summer months by accumulated cases is clear, but we found no explanation for those small peaks of incidence in the months of December and January for C. coli.

Our data are in line with the overall resistance data issued by the Spanish authorities, for example it cites resistance levels in 2018 in C. jejuni of 90.1% and 80.1% for ciprofloxacin and tetracycline respectively, when in our case they would reach 92.68% and 84.95% respectively. In the case of C. coli, this report talks about resistance of 93.3% for ciprofloxacin and tetracycline, reaching in our area percentages of 81.48% and 74.07% respectively. For erythromycin in C. coli the resistance in Spain was of 26.7% in 2018, being in our case 14.8% although in some years it has reached 36% resistance as in 2017 or 34.8% in 2016.13 It would also be in line with what was published in our country about Campylobacter spp. and antibiotic resistance in livestock, with proportion of resistance, for example, to ERY in C. coli very high (67%) for pigs, high (35%) for broilers and turkeys, and moderate (19%) for cattle, and values in C. jejuni from all host species were <3% and significantly lower than those from C. coli.14

Finally campylobacteriosis has remained relatively stable in our area of influence as in other parts of Spain.15

ConclusionsAlthough there is an overall decrease in campylobacteriosis we found an increase in C. coli cases in the last year that will need to be analyzed in more detail, but we suspect that the new proteomic identification systems have to do with the best identification among Campylobacter species. There is a significant difference in distribution relative to age, more frequent being C. jejuni in paediatric age, especially in the first years of life. Regarding gender distribution of campylobacteriosis is more common in men. Infection by C. coli does not follow a seasonal pattern, it is constant throughout the year, while against C. jejuni it is more frequent in summer and autumn. There is no seasonality. The percentage of antibiotic resistance analyzed is in line with the resistance observed at the national level. Increased antibiotic resistance is also observed in C. coli, significant for erythromycin.

In conclusion there is not an increase of C. jejuni and its resistance in contrast to veterinary publications. On the other hand there is a not alarming increase of incidence of C. coli and its resistance in our health area, which we attribute to better identification and CMI methods, but that we must watch.

Transparency declarationsAll authors have nothing to declare. This study has not been financially supported by any Diagnostic/Pharmaceutical company.

Ethical approvalNot applicable.

FundingThis study was supported by Plan Nacional de I+D+i 2013–2016, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD16/0016/0007).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

None.