The finding of blood eosinophilia in a patient is a relatively frequent reason to refer him/her to a Clinical Department of Infectious Diseases. The doctor usually intends to rule out a parasitic disease in the autochthonous population, travellers or immigrants. It is uncommon for an eosinophilia to be produced by protozoa infection, whereas helminth parasites are more frequently associated with an increase of eosinophil counts in the infected patient. Eosinophilia can be the only abnormal finding, or it could be part of more complex clinical manifestations suffered by the patient. Furthermore, many, but not all, helminth infections are associated with eosinophilia, and the eosinophil level (low, high) differs according to parasite stages, helminth species, and worm co-infections. The purpose of the present article is to carry out a systematic review of cases and case series on helminth infections and eosinophilia reported in Spain from 1990 to 2015, making a distinction between autochthonous and imported (immigrants and travellers) cases, and studying their relationship with immunodepression situations.

La detección de eosinofilia periférica es un motivo relativamente frecuente para la remisión de un paciente a una Unidad/Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas. En general, se pretende descartar una enfermedad parasitaria, tanto en personas autóctonas como en viajeros o inmigrantes. Excepcionalmente la eosinofilia relacionada con parásitos corresponde a una protozoosis, siendo los helmintos los principales agentes causales de este hallazgo hematológico. La eosinofilia puede ser el único hallazgo anormal o formar parte del cuadro clínico-biológico del paciente. Por otro lado, no todas las helmintosis se asocian de forma sistemática a eosinofilia, y el grado de la misma difiere entre las fases de la infección y el tipo de helminto. El propósito de esta revisión es un estudio sistemático de la relación entre helmintosis y eosinofilia en la literatura española, distinguiendo los casos autóctonos e importados, así como la relación con situaciones de inmunodepresión.

The term “eosinophilia” indicates the raising in the number or percentage of polymorphonuclear-eosinophil leukocytes in any solid or liquid tissue.1 Although no limit has been established, it is considered that eosinophilia exists when blood values surpass 450cells/μl.1 Their detection in the blood requires an investigation of the cause responsible, as it may arise from highly diverse causes, from mild conditions (e.g. allergic rhinitis) to severe processes (e.g. tumours of the hermatopoietic and lymphoid tissues).1 One of the main conditions leading to detection of eosinophilia is the presence of a parasitic disease. Furthermore, and with few exceptions (Isospora belli, Dientamoeba fragilis, Sarcocystis spp.), the protozoa are not the agents connected to the appearance of eosinophilia, and their presence suggests helminthosis.1

In Spain extensive literature exists regarding the association between infection by helminthes and the presence of eosinophilia. The global map of this association in Spain is complex, since in several cases parasitism is detected in isolated cases, and in others, in form of outbreaks. Several parasitic diseases also only appear as imported diseases (travellers or immigrants) whilst others have a more cosmopolitan distribution.2 Thirdly, the presence of eosinophilia depends on the life cycle stage of the parasite and even of response to treatment. Finally, several factors such as age, the patient's geographical origin, their immunological status and the presence of polyparasitism are determining factors in the detection of eosinophilia.

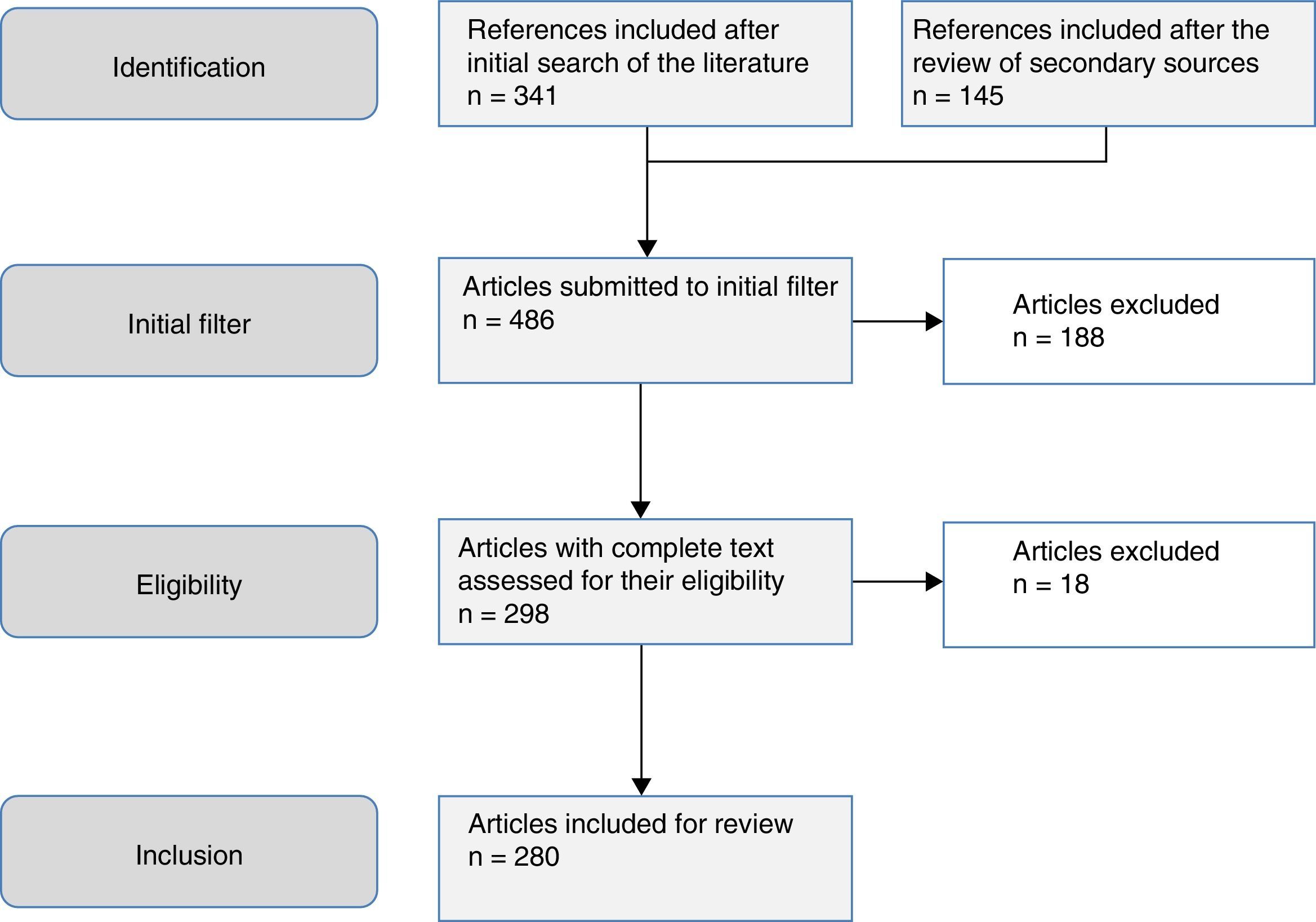

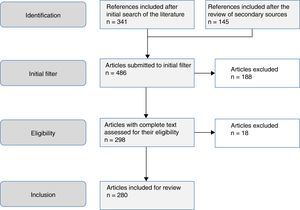

The aim of this study was to review the helminths associated with eosinophilia in Spain during the last 25 years. This study is based on a systematic search in PubMed, which included originals, brief originals, clinical notes and scientific letters (Fig. 1). The electronic search strategy was as follows: country (Spain) AND disease OR agent. The following MESH terms were considered in the inclusion of diseases: Helminthiasis, Taeniasis, Hymenolepiasis, Dipylidiasis, Cysticercosis, Echinococcosis, Sparganosis, Diphyllobothriasis, Schistosomiasis, Fascioliasis, Paragonimiasis Opisthorchiasis, Clonorchiasis, Dicrocoeliasis, Enterobiasis, Ancylostomiasis, Necatoriasis, Ascariasis, Trichuriasis, Strongyloidiasis, Dirofilariasis, Filariasis, Loiasis, Onchocerciasis, Mansonelliasis, Dracunculiasis, Trichinellosis, Anisakiasis, Toxocariasis, Gnathostomiasis. With regard to the agents, the following MESH terms were included: Helminth, Taenia, Hymenolepis, Dipylidium, Cysticercus, Echinococcus, Spirometra, Sparganum, Schistosoma, Fasciola, Paragonimus, Opisthorchis, Clonorchis, Heterophyes, Metagonimus, Dicrocoelium, Ancylostoma, Necator, Hookworm, Ascaris, Trichuris, Strongyloides, Capillaria, Dirofilaria, Wuchereria, Brugia, Loa, Onchocerca, Mansonella, Dracunculus, Trichinella, Anisakis, Toxocara, Gnathostoma. Results were restricted to studies carried out in humans. The search period lasted from January 1st 1990 to 31st August 2015.

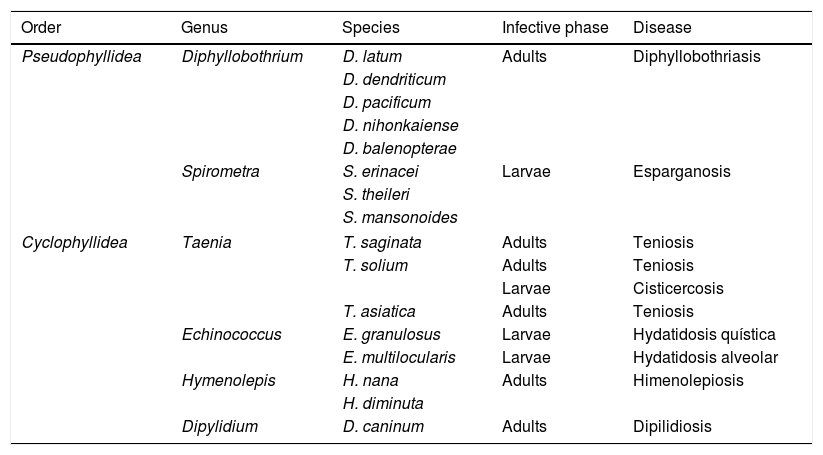

CestodiasisCestodiasis are diseases caused by flat worms (phylum Plathelminthes) with a segmented body (Cestoda classification). The main agents of the disease in humans include 2 types, Pseudophyllidea and Cyclophyllidea, and may cause the disease either through the adult form of the parasite or through the larva stage or both. Table 1 indicates the main types of cestodiasis. In general, we may state that the eosinophilia associated with the cestodiasis is mild or moderate, and often does not appear during the course of the disease. Eosinophilia is also more common in larval cestodiasis (with tissue compromise) than in those produced by adult worms (with isolated intestinal compromise). Finally, the rupture or surgical manipulation of larval forms (especially in cystic echinococcosis and to a lesser degree in alveolar echinococcosis) is associated with a notable raising in the number eosinophils in the bloodstream.

Main cestodiasis.

| Order | Genus | Species | Infective phase | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudophyllidea | Diphyllobothrium | D. latum | Adults | Diphyllobothriasis |

| D. dendriticum | ||||

| D. pacificum | ||||

| D. nihonkaiense | ||||

| D. balenopterae | ||||

| Spirometra | S. erinacei | Larvae | Esparganosis | |

| S. theileri | ||||

| S. mansonoides | ||||

| Cyclophyllidea | Taenia | T. saginata | Adults | Teniosis |

| T. solium | Adults | Teniosis | ||

| Larvae | Cisticercosis | |||

| T. asiatica | Adults | Teniosis | ||

| Echinococcus | E. granulosus | Larvae | Hydatidosis quística | |

| E. multilocularis | Larvae | Hydatidosis alveolar | ||

| Hymenolepis | H. nana | Adults | Himenolepiosis | |

| H. diminuta | ||||

| Dipylidium | D. caninum | Adults | Dipilidiosis | |

The cestodiasis diagnosed most frequently in Spain is, without a doubt, that of infections caused by the parasites of the order Cyclophyllidea. Among them, the lowest number of references corresponds to the intestinal types. Although the recording of intestinal infection caused by Taenia sp., is relatively frequent, as shown by indirect data (personal cases in the Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria) and samples sent to the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, few cases have been published in the literature.3 Infection by Hymenolepis nana has been reported in Spain, mainly in cases of Sahrawi children from Tindouf who are spending their summer holidays in Spain. Prevalence is 6.5–7.5% and there is frequent co-parasitism with intestinal protozoa (Giardia intestinalis).4,5 A case of infection by this helminth has also been reported anecdotally in a child from Ecuador.6 We only found one case published on Hymenolepis diminuta in a child aged 5 in the province of Guadalajara.7 In the review carried out we did not locate cases of infection in humans by Dipylidium caninum. However, the detection of eggs from the parasite in dog faeces in several regions of Spain,8–11 suggests that this parasitism could be under-diagnosed.

In contrast, the larval forms of cestodiasis are common, both as autochthonous parasitism or imported. The 2 major ones are cystic hydatidosis and cysticercosis, and particularly in its neurological form (neurocysticercosis).

Cystic hydatidosis produced by Echinococcus granulosus is an autochthonous zoonotic disease, endemic in the Iberian peninsula, which had major socio-economic repercussions up to the end of the 20th century.12–15 Historically the most affected regions were the Northern communities (Basque Country, Navarre, Aragon, La Rioja, Cantabria) and the central regions (Castille and Leon, Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha).15–22 Moreover, in recent years a large number of cases were reported in the Community of Valencia.23 However, we found no published cases of cystic hydatidosis in the Canary Island Community or the Balearic Island communities. Hydatidosis was significantly reduced thanks to the control programmes introduced in the eighties and nineties, although direct and indirect data exist, such as the presence of new cases of infants or the maintenance of high levels of infection in young people in the last few years, which suggest a re-emergence of the disease.12,13 In Spain, just as in other parts of the world, the most common clinical manifestations of this disease are liver24–27 and bile duct28,29 compromise and secondly derive from respiratory system lesions.18,30–33 Furthermore, several Spanish groups have reported cases or series of “atypical” forms of cystic hydatidosis which were intra-abdominal (splenic,34–36 pancreatic,20 renal,37 ovarian38 and other less common forms17,39–41) such as in other organs (heart,42–45 muscles and skeleton,21,46,47 bone48,49 or skin and soft tissues50). Several cases of imported cystic hydatidosis have also been reported, although they are scarce and not well characterised.51–53 The presence of eosinophilia is highly uncommon in the classic cystic hydatidosis, but a high rate of incidence has been published in several extra pulmonary forms, and particularly renal,37 or after rupture of the cysts (spontaneous or during surgery).54–56

Alveolar hydatidosis, cause by Echinococcus multilocularis, is exceptional in Spain, both in its autochthonous form and its imported form. There have only been 2 references in the literature in the last 25 years. These cases presented in the usual manner with similar symptoms to a primary liver tumour.57,58

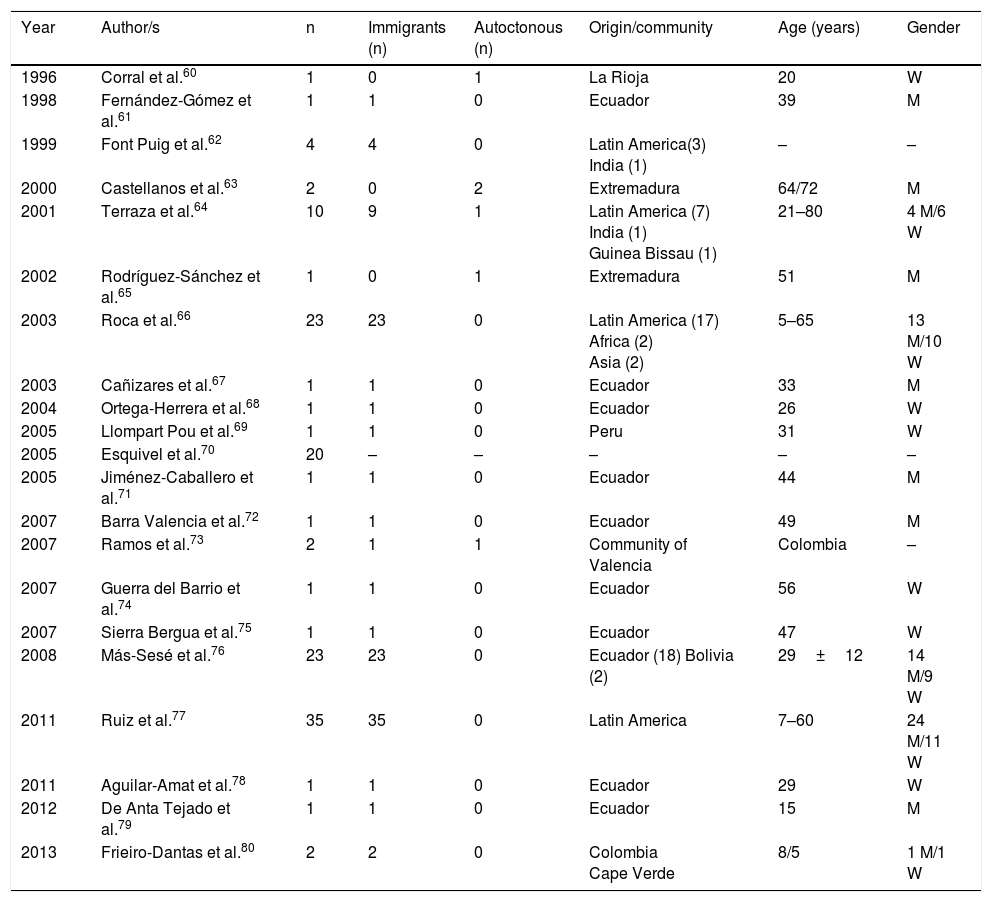

Cysticercosis is a disease caused by the larvae of Taenia solium (Cysticercus cellulosae). The 3 main locations of the larval forms are cutaneous, ocular and neurological. The most severe cases are logically those which affect the central nervous system and a few cases have been published in Spain, with mixed forms.59Table 2 displays the epidemiological data of the cases and the series of neurocysticercosis published in Spain.60–80 As maybe observed, and has already been reported in other references,60–82 there are 2 different patterns of the disease: (a) imported, which includes the greater part of cases detected in the last few years, and particularly those observed in immigrants with an age range from infancy to middle age, and (b) autochthonous, with rare cases, and reported in Spaniards over the age of 18. The main origin of the imported cases is Latin American (mostly Ecuador, Peru, Colombia and Bolivia), although a few cases of patients also come from Africa (Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, the Ivory Coast) and Asia (India and China.)64,66–69,74–80 Most autochthonous cases were described in Extremadura, La Rioja, Madrid and the Community of Valencia. In the imported cases there is a similar number of males and females, whilst in the autochthonous cases there is a clear predominance of males. In general, neurocysticercosis presents in immune-competent people although in Spain several cases have been reported in people infected with HIV73 and those with transplants.72 From the clinical viewpoint, the most frequent manifestations of neurocysticercosis are epileptic crises (of different types)and headaches. However, in Spain other unusual presentations have been reported, such as blepharospasm,83 Bruns syndrome (sudden headache associated with acute vestibular syndrome related to sudden movements of the head),71,78 medullar lesions,60 psychiatric changes79 and sudden death.69 The presence of eosinophilia in patients with neurocysticercosis is exceptional and for the most part, poorly documented.84–86

Neurocysticercosis in Spain.

| Year | Author/s | n | Immigrants (n) | Autoctonous (n) | Origin/community | Age (years) | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Corral et al.60 | 1 | 0 | 1 | La Rioja | 20 | W |

| 1998 | Fernández-Gómez et al.61 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 39 | M |

| 1999 | Font Puig et al.62 | 4 | 4 | 0 | Latin America(3) India (1) | – | – |

| 2000 | Castellanos et al.63 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Extremadura | 64/72 | M |

| 2001 | Terraza et al.64 | 10 | 9 | 1 | Latin America (7) India (1) Guinea Bissau (1) | 21–80 | 4 M/6 W |

| 2002 | Rodríguez-Sánchez et al.65 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Extremadura | 51 | M |

| 2003 | Roca et al.66 | 23 | 23 | 0 | Latin America (17) Africa (2) Asia (2) | 5–65 | 13 M/10 W |

| 2003 | Cañizares et al.67 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 33 | M |

| 2004 | Ortega-Herrera et al.68 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 26 | W |

| 2005 | Llompart Pou et al.69 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Peru | 31 | W |

| 2005 | Esquivel et al.70 | 20 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2005 | Jiménez-Caballero et al.71 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 44 | M |

| 2007 | Barra Valencia et al.72 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 49 | M |

| 2007 | Ramos et al.73 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Community of Valencia | Colombia | – |

| 2007 | Guerra del Barrio et al.74 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 56 | W |

| 2007 | Sierra Bergua et al.75 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 47 | W |

| 2008 | Más-Sesé et al.76 | 23 | 23 | 0 | Ecuador (18) Bolivia (2) | 29±12 | 14 M/9 W |

| 2011 | Ruiz et al.77 | 35 | 35 | 0 | Latin America | 7–60 | 24 M/11 W |

| 2011 | Aguilar-Amat et al.78 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 29 | W |

| 2012 | De Anta Tejado et al.79 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Ecuador | 15 | M |

| 2013 | Frieiro-Dantas et al.80 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Colombia Cape Verde | 8/5 | 1 M/1 W |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

Infections by parasites of the Pseudophyllidea order are rare in Spain. Among these, most references correspond to cases of the diphyllobothriasis.87–91 Only one case of sparganosis (infection by difference species of Spirometran) was recently reported. This was an imported sparganosis by a male aged 29 from Bolivia, with symptoms of convulsions and multi-cystic cerebral lesion and who was diagnosed with suspected dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour (DNET).92 With regard to diphyllobothriasis, the symptoms of this disease may not be present or may present non-specific abdominal upset which may or may not be associated with megaloblastic anaemia. Of the published cases in Spain, most are autochthonous, and diagnosed in a broad range of ages (3–71 years). The most frequently detected species is Diphyllobothrium latum, although cases caused by Diphyllobothrium pacificum and Diplogonoporus balaenopterae90 have also been reported. These are possibly related to the consumption of imported fish or travel abroad. Eosinophilia is exceptional in the cases published in Spain.

TrematodosisTrematodosis are diseases produced by flatworm (phylum Plathelminthes) with unsegmented foliaceus body (Trematoda class). Most are hermaphrodites, with the exception of the genus Schistosoma, which present sexual dimorphism and characteristic morphology.

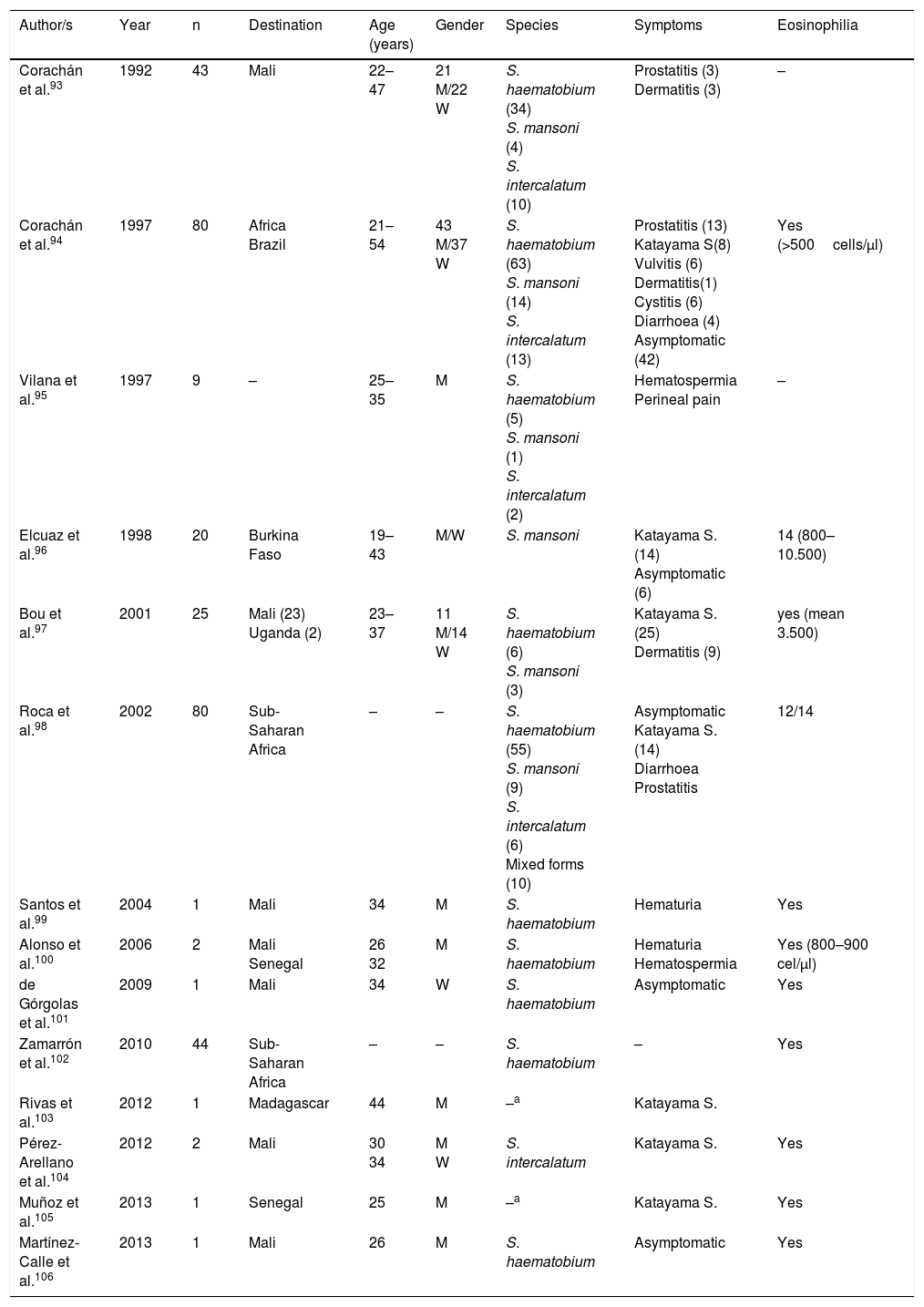

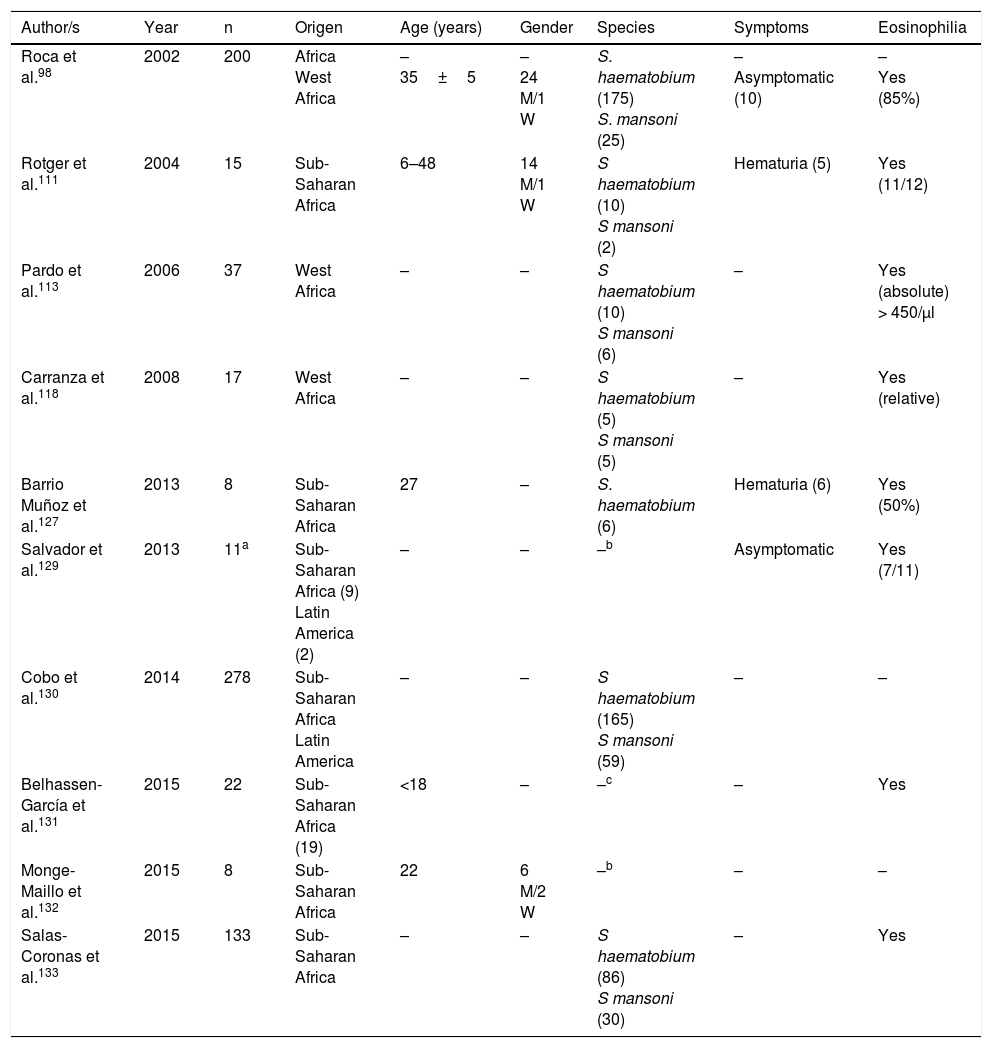

SchistosomiasisAll cases published in Spain on this disease correspond to imported forms. However, symptoms and biology differ notably between infections detected in travellers and those diagnosed in immigrants (Tables 3–5).

Schistosomiasis imported by travellers (cases and series).

| Author/s | Year | n | Destination | Age (years) | Gender | Species | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corachán et al.93 | 1992 | 43 | Mali | 22–47 | 21 M/22 W | S. haematobium (34) S. mansoni (4) S. intercalatum (10) | Prostatitis (3) Dermatitis (3) | – |

| Corachán et al.94 | 1997 | 80 | Africa Brazil | 21–54 | 43 M/37 W | S. haematobium (63) S. mansoni (14) S. intercalatum (13) | Prostatitis (13) Katayama S(8) Vulvitis (6) Dermatitis(1) Cystitis (6) Diarrhoea (4) Asymptomatic (42) | Yes (>500cells/μl) |

| Vilana et al.95 | 1997 | 9 | – | 25–35 | M | S. haematobium (5) S. mansoni (1) S. intercalatum (2) | Hematospermia Perineal pain | – |

| Elcuaz et al.96 | 1998 | 20 | Burkina Faso | 19–43 | M/W | S. mansoni | Katayama S. (14) Asymptomatic (6) | 14 (800–10.500) |

| Bou et al.97 | 2001 | 25 | Mali (23) Uganda (2) | 23–37 | 11 M/14 W | S. haematobium (6) S. mansoni (3) | Katayama S. (25) Dermatitis (9) | yes (mean 3.500) |

| Roca et al.98 | 2002 | 80 | Sub-Saharan Africa | – | – | S. haematobium (55) S. mansoni (9) S. intercalatum (6) Mixed forms (10) | Asymptomatic Katayama S. (14) Diarrhoea Prostatitis | 12/14 |

| Santos et al.99 | 2004 | 1 | Mali | 34 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | Yes |

| Alonso et al.100 | 2006 | 2 | Mali Senegal | 26 32 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria Hematospermia | Yes (800–900 cel/μl) |

| de Górgolas et al.101 | 2009 | 1 | Mali | 34 | W | S. haematobium | Asymptomatic | Yes |

| Zamarrón et al.102 | 2010 | 44 | Sub-Saharan Africa | – | – | S. haematobium | – | Yes |

| Rivas et al.103 | 2012 | 1 | Madagascar | 44 | M | –a | Katayama S. | |

| Pérez-Arellano et al.104 | 2012 | 2 | Mali | 30 34 | M W | S. intercalatum | Katayama S. | Yes |

| Muñoz et al.105 | 2013 | 1 | Senegal | 25 | M | –a | Katayama S. | Yes |

| Martínez-Calle et al.106 | 2013 | 1 | Mali | 26 | M | S. haematobium | Asymptomatic | Yes |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

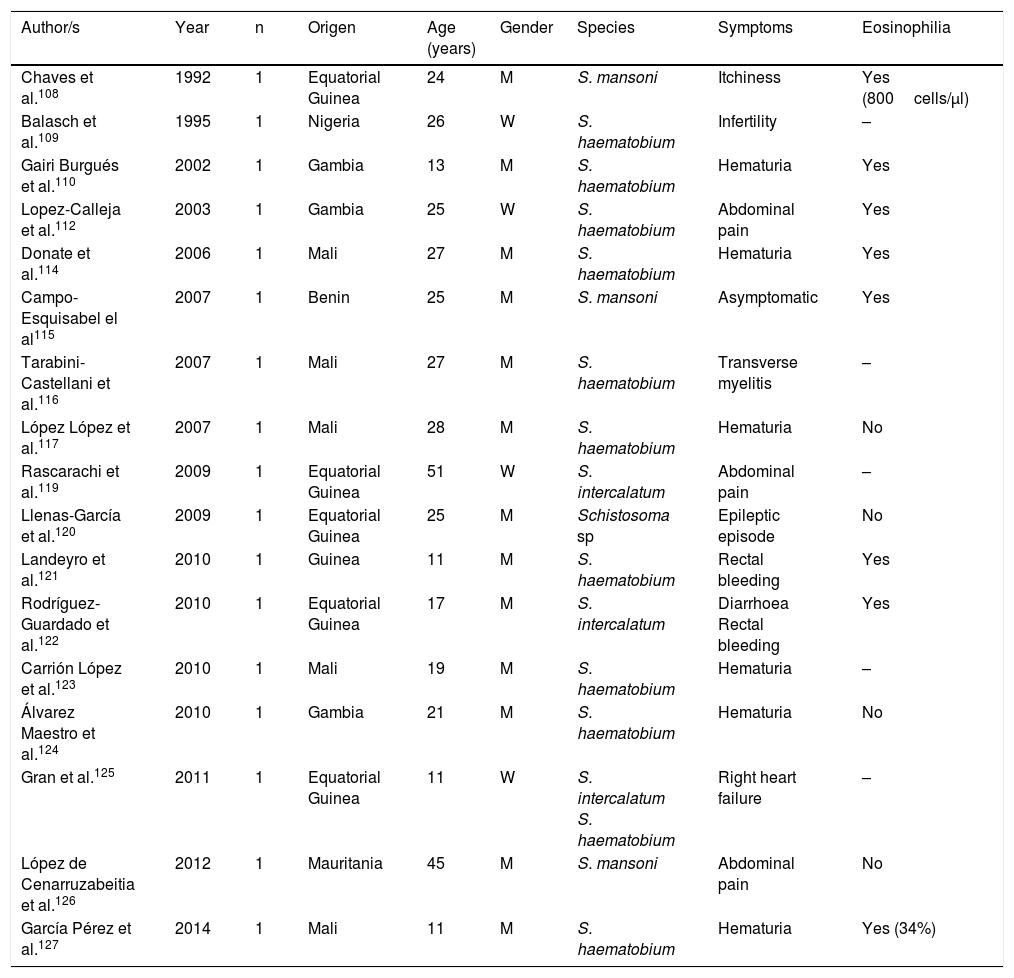

Schistosomiasis imported by immigrants (isolated cases).

| Author/s | Year | n | Origen | Age (years) | Gender | Species | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaves et al.108 | 1992 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 24 | M | S. mansoni | Itchiness | Yes (800cells/μl) |

| Balasch et al.109 | 1995 | 1 | Nigeria | 26 | W | S. haematobium | Infertility | – |

| Gairi Burgués et al.110 | 2002 | 1 | Gambia | 13 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | Yes |

| Lopez-Calleja et al.112 | 2003 | 1 | Gambia | 25 | W | S. haematobium | Abdominal pain | Yes |

| Donate et al.114 | 2006 | 1 | Mali | 27 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | Yes |

| Campo-Esquisabel el al115 | 2007 | 1 | Benin | 25 | M | S. mansoni | Asymptomatic | Yes |

| Tarabini-Castellani et al.116 | 2007 | 1 | Mali | 27 | M | S. haematobium | Transverse myelitis | – |

| López López et al.117 | 2007 | 1 | Mali | 28 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | No |

| Rascarachi et al.119 | 2009 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 51 | W | S. intercalatum | Abdominal pain | – |

| Llenas-García et al.120 | 2009 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 25 | M | Schistosoma sp | Epileptic episode | No |

| Landeyro et al.121 | 2010 | 1 | Guinea | 11 | M | S. haematobium | Rectal bleeding | Yes |

| Rodríguez-Guardado et al.122 | 2010 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 17 | M | S. intercalatum | Diarrhoea Rectal bleeding | Yes |

| Carrión López et al.123 | 2010 | 1 | Mali | 19 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | – |

| Álvarez Maestro et al.124 | 2010 | 1 | Gambia | 21 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | No |

| Gran et al.125 | 2011 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 11 | W | S. intercalatum S. haematobium | Right heart failure | – |

| López de Cenarruzabeitia et al.126 | 2012 | 1 | Mauritania | 45 | M | S. mansoni | Abdominal pain | No |

| García Pérez et al.127 | 2014 | 1 | Mali | 11 | M | S. haematobium | Hematuria | Yes (34%) |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

Schistosomiasis imported by immigrants (series).

| Author/s | Year | n | Origen | Age (years) | Gender | Species | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roca et al.98 | 2002 | 200 | Africa West Africa | – 35±5 | – 24 M/1 W | S. haematobium (175) S. mansoni (25) | – Asymptomatic (10) | – Yes (85%) |

| Rotger et al.111 | 2004 | 15 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 6–48 | 14 M/1 W | S haematobium (10) S mansoni (2) | Hematuria (5) | Yes (11/12) |

| Pardo et al.113 | 2006 | 37 | West Africa | – | – | S haematobium (10) S mansoni (6) | – | Yes (absolute) > 450/μl |

| Carranza et al.118 | 2008 | 17 | West Africa | – | – | S haematobium (5) S mansoni (5) | – | Yes (relative) |

| Barrio Muñoz et al.127 | 2013 | 8 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 27 | – | S. haematobium (6) | Hematuria (6) | Yes (50%) |

| Salvador et al.129 | 2013 | 11a | Sub-Saharan Africa (9) Latin America (2) | – | – | –b | Asymptomatic | Yes (7/11) |

| Cobo et al.130 | 2014 | 278 | Sub-Saharan Africa Latin America | – | – | S haematobium (165) S mansoni (59) | – | – |

| Belhassen-García et al.131 | 2015 | 22 | Sub-Saharan Africa (19) | <18 | – | –c | – | Yes |

| Monge-Maillo et al.132 | 2015 | 8 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 22 | 6 M/2 W | –b | – | – |

| Salas-Coronas et al.133 | 2015 | 133 | Sub-Saharan Africa | – | – | S haematobium (86) S mansoni (30) | – | Yes |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

With regard to travellers, isolated cases and series have been reported in several Spanish regions.93–106 Practically all patients had travelled to Africa, with the most visited countries being Mali (particularly Dogon country), Burkina Fasso, Uganda (Sesé island), Malawi, Senegal and Madagascar. In general, the disease is more common in males and affects middle aged people(which are congruent with the common international traveller profile). The main species responsible is Schistosoma haematobium, followed by Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma intercalatum. Mixed forms of parasitism are also common. Symptoms are similar to acute schistosomiasis, with Katayama syndrome98,103–105 and bather's dermatitis97 as the most common symptoms. Other major changes of the disease are genital-urinary (hematuria, prostatitis, hematospermia).93–95,98,99 We should note that the first description of hematospermia as a sign of schistosomiasis was reported by Spanish authors.107 One interesting factors is the detection of asymptomatic patients, which together with the different interval between exposure and appearance of symptoms in people with the same outbreak, suggests the presence of host factors modulate the expression of the disease. With regard to eosinophilia, this is present in acute forms, generally high but variable, among people of the same outbreak.

Schistosomiasis in Immigrants presents similarities but also major differences with regard to the forms described in travellers.101,108–133 Thus most cases originate from sub-Saharan Africa, particularly West Africa and specifically the countries of Mali, Equatorial Guinea and Mauritania. In immigrants, schistosomiasis also predominates in males, although the age interval is higher, with cases in children and older adults. S. haematobium is the most common agent, followed by S. mansoni and S. intercalatum. Symptoms are highly varied, with hematuria (micro or macroscopic) being the most common factor, and related to the infection by S. haematobium and secondly abdominal pain in infections by S. mansoni and S. intercalatum. Furthermore, in Spain there have been several cases with atypical symptoms and complications of the disease. Specifically, some of the most serious forms of the parasitosis (neuroschistosomiasis)134 have been reported, and specifically transverse myelitis 115,116 and a hemispheric focal lesion, with hemiparesis and convulsions.125 Other complications described in immigrants in Spain are female infertility,109 pulmonary hyptertension125 and acute appendicitis.126 Also, in the population under study a large number of cases of schistosomiasis are asymptomatic. Eosinophilia in imported schuistosomosis in immigrants is highly variable. Absolute eosinophilia (mild-moderate) has been detected in several cases, relative eosinophilia in others and no identification of this change in the remainder. A screening for these disease in immigrants coming from areas under risk would be reasonable, bearing in mind the relevance of the long-term complications (e.g. portal hypertension, squamous cancer of the bladder).

A major problem of schistosomiasis is complex diagnosis. In acute cases it is very common for no eggs to be present in urine or faeces and in chronic cases the elimination of eggs is intermittent. Radiologic studies135 and cytoscope123 may help when there is suspected diagnosis, particularly in cases of infection by S. haematobium. Serology has been a standard test to detect several acute cases and other parasitological negative cases, although there are many limitations.136,137 Application of standard molecular biological techniques (PCR) has not been useful in clinical samples nor proven their usefulness in clinical practice.138,139 New diagnostic procedures (LAMP) are current under development, with promising results.140

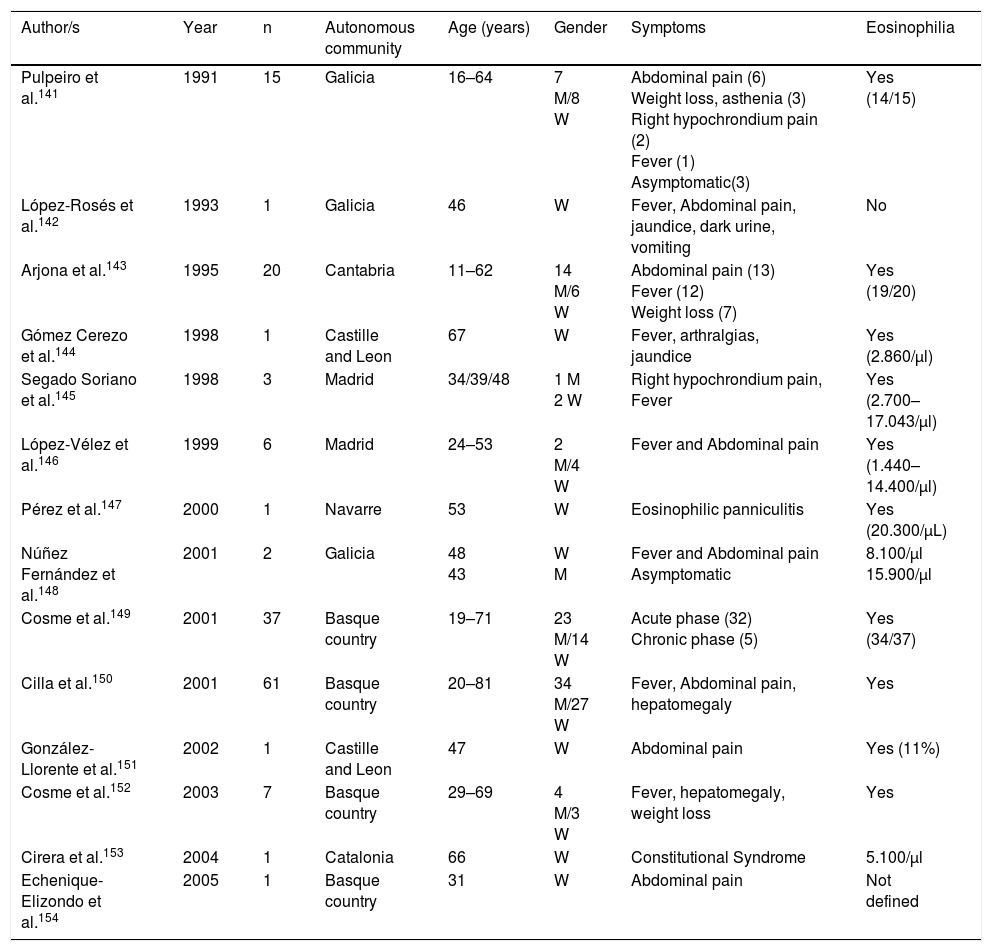

Trematodosis by hermaphrodite speciesThe most common autochthonous trematodosis in Spain is fasciolosis, a disease caused by Fasciola hepatica in Spain and related to the ingestion of metacercariae which are present in vegetables (mainly cress).141–154 With few exceptions, the cases reported are autochthonous and their analysis in the last 25 years (Table 6) has enabled us to made several generalisations: (1) Most published cases correspond to patients from the northern half of the Iberian peninsula (Basque country, Galicia, Cantabria, Navarre and Castille Leon). (2) During the reviewed period a notable reduction in cases was observed, thoroughly documented in Guipúzcoa.150 In fact, we are unaware of cases published in Spain since 2005, which does not exclude the presence of isolated cases diagnosed in hospitals and benchmark centres. (3) Most cases are reported in adults, with similar prevalence in men and women. (4) The most common clinical symptoms correspond to the acute phase of the disease with constitutional syndrome associated with right hypochondriac pain, and chronic changes (compromise of bile duct) are less habitual. (5) Atypical symptoms are infrequent (subcutaneous nodules, eosinophilic panniculitis, pulmonary infiltrates, pleuropericarditis, meningitis or swollen lymph nodes)141,143,147 and local complications (e.g., pancreatitis) or hepatic subcapsular abscess.151,154 (6) Eosinophilia is constant in the disease, usually with very high rates and is the main reason for suspicion of this disease.

Fasciolosis in Spain.

| Author/s | Year | n | Autonomous community | Age (years) | Gender | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulpeiro et al.141 | 1991 | 15 | Galicia | 16–64 | 7 M/8 W | Abdominal pain (6) Weight loss, asthenia (3) Right hypochrondium pain (2) Fever (1) Asymptomatic(3) | Yes (14/15) |

| López-Rosés et al.142 | 1993 | 1 | Galicia | 46 | W | Fever, Abdominal pain, jaundice, dark urine, vomiting | No |

| Arjona et al.143 | 1995 | 20 | Cantabria | 11–62 | 14 M/6 W | Abdominal pain (13) Fever (12) Weight loss (7) | Yes (19/20) |

| Gómez Cerezo et al.144 | 1998 | 1 | Castille and Leon | 67 | W | Fever, arthralgias, jaundice | Yes (2.860/μl) |

| Segado Soriano et al.145 | 1998 | 3 | Madrid | 34/39/48 | 1 M 2 W | Right hypochrondium pain, Fever | Yes (2.700–17.043/μl) |

| López-Vélez et al.146 | 1999 | 6 | Madrid | 24–53 | 2 M/4 W | Fever and Abdominal pain | Yes (1.440–14.400/μl) |

| Pérez et al.147 | 2000 | 1 | Navarre | 53 | W | Eosinophilic panniculitis | Yes (20.300/μL) |

| Núñez Fernández et al.148 | 2001 | 2 | Galicia | 48 43 | W M | Fever and Abdominal pain Asymptomatic | 8.100/μl 15.900/μl |

| Cosme et al.149 | 2001 | 37 | Basque country | 19–71 | 23 M/14 W | Acute phase (32) Chronic phase (5) | Yes (34/37) |

| Cilla et al.150 | 2001 | 61 | Basque country | 20–81 | 34 M/27 W | Fever, Abdominal pain, hepatomegaly | Yes |

| González-Llorente et al.151 | 2002 | 1 | Castille and Leon | 47 | W | Abdominal pain | Yes (11%) |

| Cosme et al.152 | 2003 | 7 | Basque country | 29–69 | 4 M/3 W | Fever, hepatomegaly, weight loss | Yes |

| Cirera et al.153 | 2004 | 1 | Catalonia | 66 | W | Constitutional Syndrome | 5.100/μl |

| Echenique-Elizondo et al.154 | 2005 | 1 | Basque country | 31 | W | Abdominal pain | Not defined |

Paragonimosis, caused by different species of Paragonimus, is an uncommon trematodosis in Spain and always diagnosed as an imported disease (2 patients in Equatorial Guinea and one in Ecuador).155–157 Clinical symptoms are most commonly respiratory, imitating tuberculosis, which is also frequently associated with it. It is very common to find eosinophilia in patients with paragonimosis.

Infections by oriental varieties (Opisthorchis spp., Clonorchis spp., Metagonimus spp. or Heterophyes spp.) are exceptional in Spain, with the description of a single case in one south eastern Asiatic immigrant.158

To conclude this section we should point out the presence of false parasitisms by Dicrocoelium dendriticum in immigrants (elimination of eggs in faeces without causing the disease). This trematode which parasitises the bile ducts of herbivores may cause disease in humans, although the most frequent occurrence is the expulsion of eggs in faeces after the ingestion of raw infected animal liver. The cases described in Spain principally correspond to people of sub-Saharan origin and more infrequently from North Africa.159–161

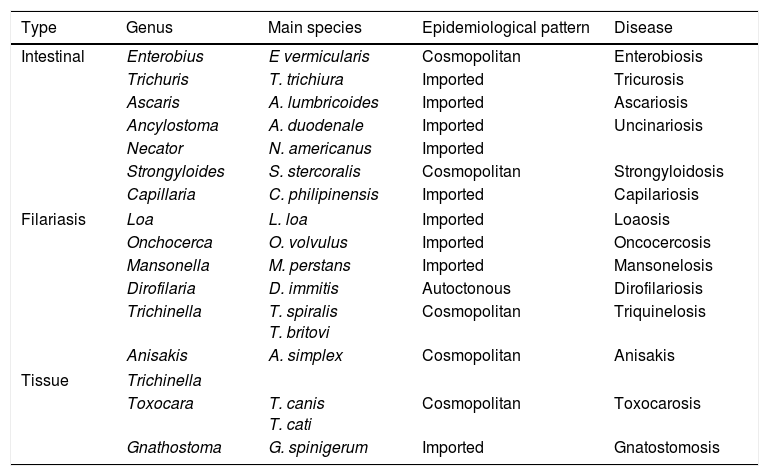

NematodosisNematodosis are helminthosis produced by parasites of the phylum Nematoda, characterised by the cylindrical shape of the worms and the presence of sexual dimorphism. From a clinical viewpoint, they may be classified into 3 large groups: intestinal, haematic/dermal/ocular (filariosis) and tissue (Table 7).

Principal nematodosis in Spain.

| Type | Genus | Main species | Epidemiological pattern | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal | Enterobius | E vermicularis | Cosmopolitan | Enterobiosis |

| Trichuris | T. trichiura | Imported | Tricurosis | |

| Ascaris | A. lumbricoides | Imported | Ascariosis | |

| Ancylostoma | A. duodenale | Imported | Uncinariosis | |

| Necator | N. americanus | Imported | ||

| Strongyloides | S. stercoralis | Cosmopolitan | Strongyloidosis | |

| Capillaria | C. philipinensis | Imported | Capilariosis | |

| Filariasis | Loa | L. loa | Imported | Loaosis |

| Onchocerca | O. volvulus | Imported | Oncocercosis | |

| Mansonella | M. perstans | Imported | Mansonelosis | |

| Dirofilaria | D. immitis | Autoctonous | Dirofilariosis | |

| Trichinella | T. spiralis T. britovi | Cosmopolitan | Triquinelosis | |

| Anisakis | A. simplex | Cosmopolitan | Anisakis | |

| Tissue | Trichinella | |||

| Toxocara | T. canis T. cati | Cosmopolitan | Toxocarosis | |

| Gnathostoma | G. spinigerum | Imported | Gnatostomosis | |

Parasitism by Enterobius vermicularis is one of the most common helminths. However, references in the Spanish literature, and especially recent references, are scarce and often discrepant.3,4,131,132,162–167 The first aspects to consider in the differences of prevalence reported are the study design and scope of study. In Gran Canaria, in a work based on the parasitological data of all health centres during one year, enterobiosis accounted for approximately a third of cases (31.5%; 301/957).3 Furthermore the prevalence of this parasitism depends on whether the study was conducted on asymptomatic peoples162–164 or in the presence of symptoms.165 A further aspect of interest is the clear predominance of those infected at paediatric age, data which could be variable depending on the geographical region second (31.5% in Gran Canaria, 20.4% in the Guadalquivir valley, 10.8% in Valencia and 1.34% in Cuenca).3,162,163 In the wholes series described, co-parasitism is normal with other intestinal nematodes and/or protozoa. Data on this infection in immigrants is scarce, with it being more common in Maghreb immigrant children3,4 and exceptionally in sub-Saharan children130,131,166 and adults.167 In addition to pathogenic reasons, the low detection of cases could be related to the absence of a systematic use of the “Graham test”.165 In general, enterobiosis is not a serious disease. It is characterised by anal and/or genital itchiness. However, several complications have been described such as eosinophilic colitis (related to the parasite larvae) or the reduction of serum concentration of metals (copper, zinc and magnesium).168 Finally, eosinophilia is mild or does not exist in most cases, with the exception of invasive forms.

Standard intestinal nematodosis are caused by uncinarias (Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus), Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris spp. (mainly Trichuris trichiura and exceptionally Trichuris vulpis).169 These diseases were well represented throughout Spain in other times but incidence has since decreased considerately thanks to improvements in hygiene and health.170 For this reason, with the exception of isolated cases and usually in people of advanced age, these diseases only appear in immigrants. Analysis of published cases in the last 25 years in Spain171–183 have led to several generalisations: (1) In the series where this type of parasitism has been studied in adults, most cases have corresponded to uncinarias, followed by Trichuris spp. and A. lumbricoides,3,113,118,133,167 with this pattern being inverted in series involving children.166 (2) Most cases correspond to immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, although cases in patients from Latin America130,172,176,181,182 and Asia179 have also been reported. (3) Co-parasitism is very common between the classical intestinal nematodes173 and other helminths and protozoa.108,115,121 (4) Symptoms are very varied and include a large number of asymptomatic caseas,2,178 either associated or not with absolute eosinophilia113,133 or relative eosinophilia,118 non-specific abdominal pains178 or the “standard” disease symptoms. The latter are the least common form of the infection by intestinal nematodes, although they are over represented in the literature. One case of infection by Trichuris spp. with a rectal polyp was reported,121 several cases of iron-deficiency anaemia in infections by uncinarias172,175,178–180,184 and local or systemic complications in the infection by A. lumbricoides (e.g. intestinal obstruction,182 bile duct/pancreatic mass obstruction,174,181,183,185 and Löffler176 syndrome or elimination of adult worm177) were reported. (5) Detection of eosinophilia and its degree of severity is highly varied, although as a general rule, it is detected in approximately half of cases and is mild or moderate.

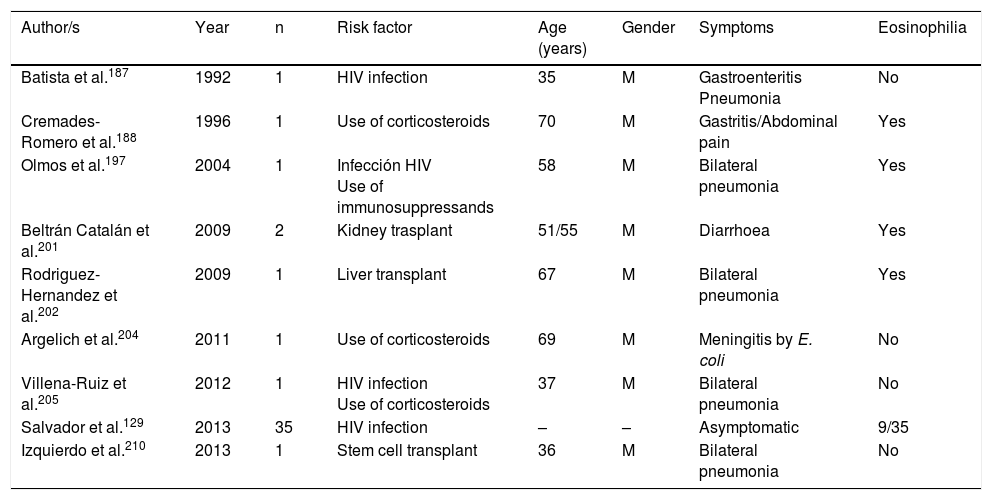

Strongyloidosis is a major parasitic disease in Spain. Analysis of isolated cases and patient series reveals several interesting characteristics.129,186–205,207–213 Firstly, there is the difficulty of completing precise diagnosis of the nematode. The standard co-proparasitological study detects a minimum proportion of cases,3,132,167 a figure which increases on using more specific techniques (e.g. the Baermann concentration test, the Harada-Mori technique and the Koga agar plate culture). However, several Spanish strongyloidosis series are based on serological diagnosis, with inherent limitations to this technique.133,211 Strongyloidosis in Spain is a disease which mainly affects adults, although there have been isolated cases in children.199 One essential aspect in strongyloidosis is the differentiation of clinical symptoms between immunocompetent and immunodepressed patients. In the immunocompetent person, this nematode is usually asymptomatic or the course of the disease is with one or several of the data of the eosinophilia-diarrhoea-skin lesion triad. However, in the immunodepressed patient the eosinophilia disappears and serious systemic symptoms may present, such as the systemic infection by intestinal microorganisms led by Strongyloids. We are interested in pointing out that the main forms of immunodepression associated with the hyperinfection syndrome correspond to the use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants, whilst the association with the HIV infection is infrequent and on many occasions linked to other risk factors (e.g. corticoid steroids or HTLV-I infection)208 (Table 8). From an epidemiological viewpoint in Spain there are 2 strongyloidosis patterns: the autochthonous and the imported forms. At present, strongyloidosis continues to be an autochthonous disease, which is why it is included in the differential diagnosis of any patient with digestive or “allergic” symptoms. Symptoms (Table 9). Notwithstanding, most cases are sporadic,195,198,209 with the exception of a specific area in Valencia (Gandía and Oliva), where an accumulation of patients with a well defined profile arose: male adults with a compatible professional history.189,191,194,215 Imported strongyloidosis however is a disease mainly described in immigrants, and exceptionally in travellers203,212 (Table 10). Unlike other imported helminths, where sub-Saharan origin predominates, a high number of cases of strongyloidosis come from Latin America.129,193,196,200,206,208,212–214 Most cases are asymptomatic, and it therefore seems reasonable to include this disease in the screening of immigrants from the before-mentioned geographical areas. In the remainder of cases, the normal symptoms are digestive and to a lesser extent, cutaneous. We should point out the detection of several cases in patients with allergic symptoms,206,207 especially of Latin American origin since the use of corticoid steroids in this context leads to hyperinfection syndrome. Eosinophilia in immunocompetent patients (autochthonous or immigrants) is highly variable (Tables 9 and 10).

Strongyloidosis and risk factors.

| Author/s | Year | n | Risk factor | Age (years) | Gender | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batista et al.187 | 1992 | 1 | HIV infection | 35 | M | Gastroenteritis Pneumonia | No |

| Cremades-Romero et al.188 | 1996 | 1 | Use of corticosteroids | 70 | M | Gastritis/Abdominal pain | Yes |

| Olmos et al.197 | 2004 | 1 | Infección HIV Use of immunosuppressands | 58 | M | Bilateral pneumonia | Yes |

| Beltrán Catalán et al.201 | 2009 | 2 | Kidney trasplant | 51/55 | M | Diarrhoea | Yes |

| Rodriguez-Hernandez et al.202 | 2009 | 1 | Liver transplant | 67 | M | Bilateral pneumonia | Yes |

| Argelich et al.204 | 2011 | 1 | Use of corticosteroids | 69 | M | Meningitis by E. coli | No |

| Villena-Ruiz et al.205 | 2012 | 1 | HIV infection Use of corticosteroids | 37 | M | Bilateral pneumonia | No |

| Salvador et al.129 | 2013 | 35 | HIV infection | – | – | Asymptomatic | 9/35 |

| Izquierdo et al.210 | 2013 | 1 | Stem cell transplant | 36 | M | Bilateral pneumonia | No |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

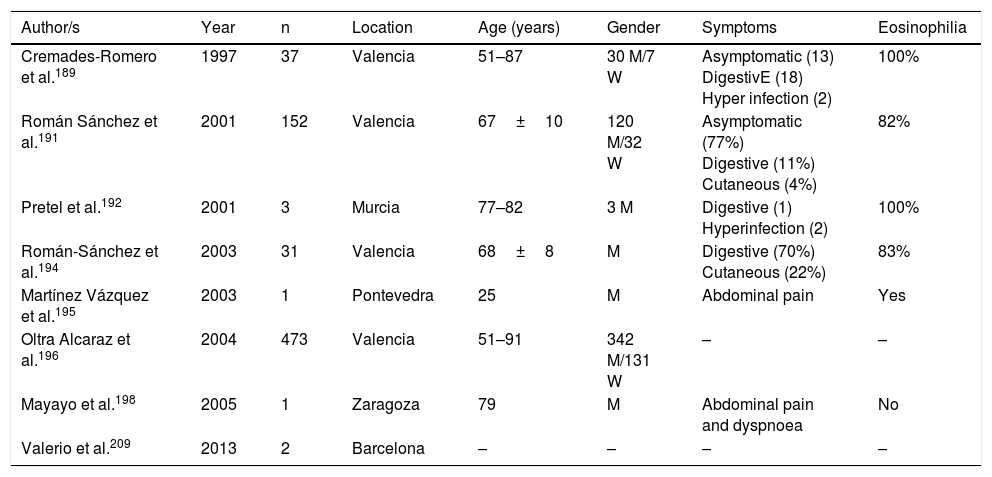

Autochthonous strongyloidosis in Spain.

| Author/s | Year | n | Location | Age (years) | Gender | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cremades-Romero et al.189 | 1997 | 37 | Valencia | 51–87 | 30 M/7 W | Asymptomatic (13) DigestivE (18) Hyper infection (2) | 100% |

| Román Sánchez et al.191 | 2001 | 152 | Valencia | 67±10 | 120 M/32 W | Asymptomatic (77%) Digestive (11%) Cutaneous (4%) | 82% |

| Pretel et al.192 | 2001 | 3 | Murcia | 77–82 | 3 M | Digestive (1) Hyperinfection (2) | 100% |

| Román-Sánchez et al.194 | 2003 | 31 | Valencia | 68±8 | M | Digestive (70%) Cutaneous (22%) | 83% |

| Martínez Vázquez et al.195 | 2003 | 1 | Pontevedra | 25 | M | Abdominal pain | Yes |

| Oltra Alcaraz et al.196 | 2004 | 473 | Valencia | 51–91 | 342 M/131 W | – | – |

| Mayayo et al.198 | 2005 | 1 | Zaragoza | 79 | M | Abdominal pain and dyspnoea | No |

| Valerio et al.209 | 2013 | 2 | Barcelona | – | – | – | – |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

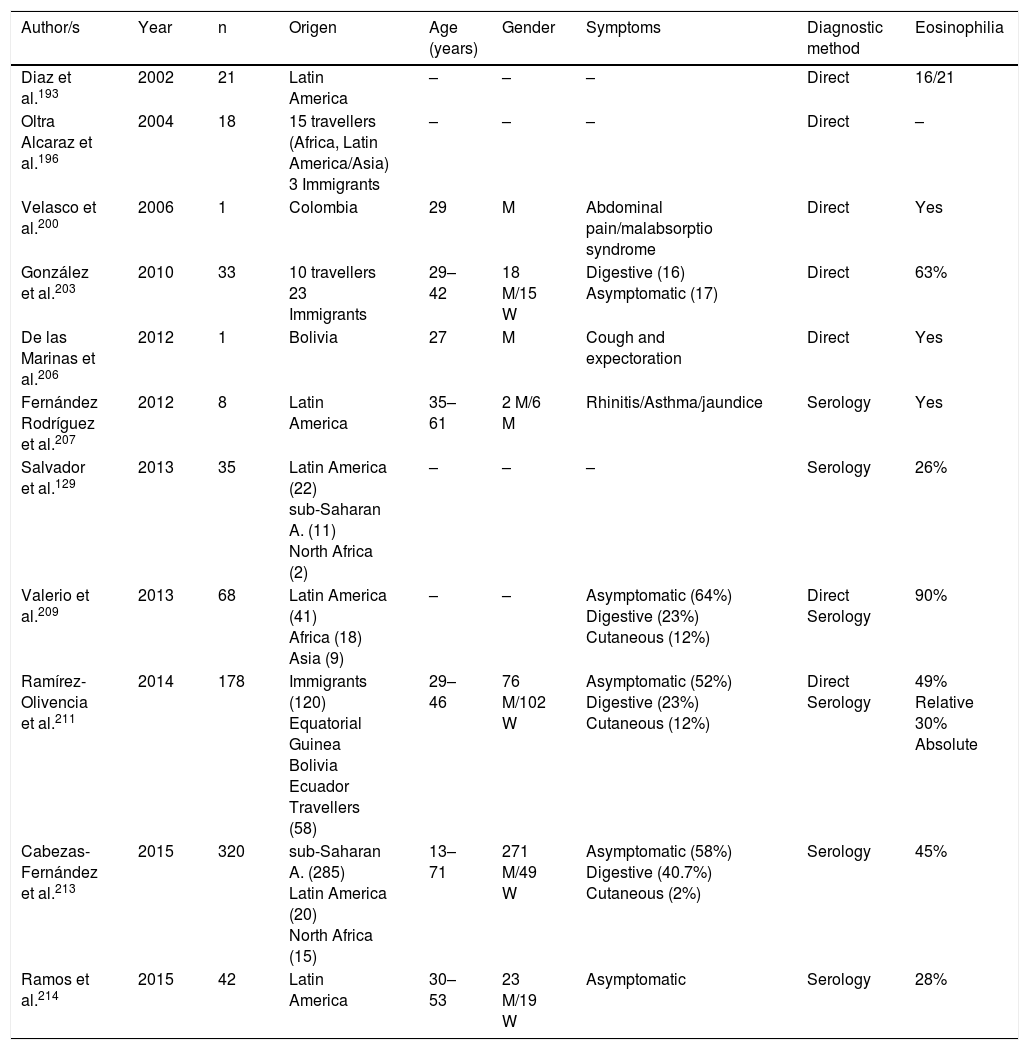

Imported strongyloidosis in Spain.

| Author/s | Year | n | Origen | Age (years) | Gender | Symptoms | Diagnostic method | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaz et al.193 | 2002 | 21 | Latin America | – | – | – | Direct | 16/21 |

| Oltra Alcaraz et al.196 | 2004 | 18 | 15 travellers (Africa, Latin America/Asia) 3 Immigrants | – | – | – | Direct | – |

| Velasco et al.200 | 2006 | 1 | Colombia | 29 | M | Abdominal pain/malabsorptio syndrome | Direct | Yes |

| González et al.203 | 2010 | 33 | 10 travellers 23 Immigrants | 29–42 | 18 M/15 W | Digestive (16) Asymptomatic (17) | Direct | 63% |

| De las Marinas et al.206 | 2012 | 1 | Bolivia | 27 | M | Cough and expectoration | Direct | Yes |

| Fernández Rodríguez et al.207 | 2012 | 8 | Latin America | 35–61 | 2 M/6 M | Rhinitis/Asthma/jaundice | Serology | Yes |

| Salvador et al.129 | 2013 | 35 | Latin America (22) sub-Saharan A. (11) North Africa (2) | – | – | – | Serology | 26% |

| Valerio et al.209 | 2013 | 68 | Latin America (41) Africa (18) Asia (9) | – | – | Asymptomatic (64%) Digestive (23%) Cutaneous (12%) | Direct Serology | 90% |

| Ramírez-Olivencia et al.211 | 2014 | 178 | Immigrants (120) Equatorial Guinea Bolivia Ecuador Travellers (58) | 29–46 | 76 M/102 W | Asymptomatic (52%) Digestive (23%) Cutaneous (12%) | Direct Serology | 49% Relative 30% Absolute |

| Cabezas-Fernández et al.213 | 2015 | 320 | sub-Saharan A. (285) Latin America (20) North Africa (15) | 13–71 | 271 M/49 W | Asymptomatic (58%) Digestive (40.7%) Cutaneous (2%) | Serology | 45% |

| Ramos et al.214 | 2015 | 42 | Latin America | 30–53 | 23 M/19 W | Asymptomatic | Serology | 28% |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

We only found one reference in the Spanish literature to the infection by Capillaria philipinensis.216 This disease is not limited to the Philippines, but is also present in Far and Middle Eastern countries, or South American, and its detection is therefore possible in imported cases. Generally capilarosis is a diarrhoea process with vomiting, although patients without treatment for several months may die due to the loss of electrolytes, or the sepsis associated with secondary bacterial infection (auto-infection processes).

FilariasisFilariasis in Spain presents 2 different patterns: autochthonous (of cosmopolitan distribution) where there are no microfilariae, and imported forms, characterised by the presence of microfilariae in blood, skin or eyeball.

The cosmopolitan forms are caused mainly by 2 species of Dirofilaria (Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens).217–220 In Spain, the 2 regions where this parasitism has been reported are Salamanca and Gran Canaria. The most common form of infection is vectoral transmission by different species of mosquitoes (Aedes spp., Anopheles spp. and Culex spp.) from infected mammals (mainly dogs). The infection takes places through immature worms, is generally asymptomatic and occasionally presents with subcutaneous, pulmonary (persitent or transitory) and ocular nodules. Eosinophilia is exceptional in these cases.

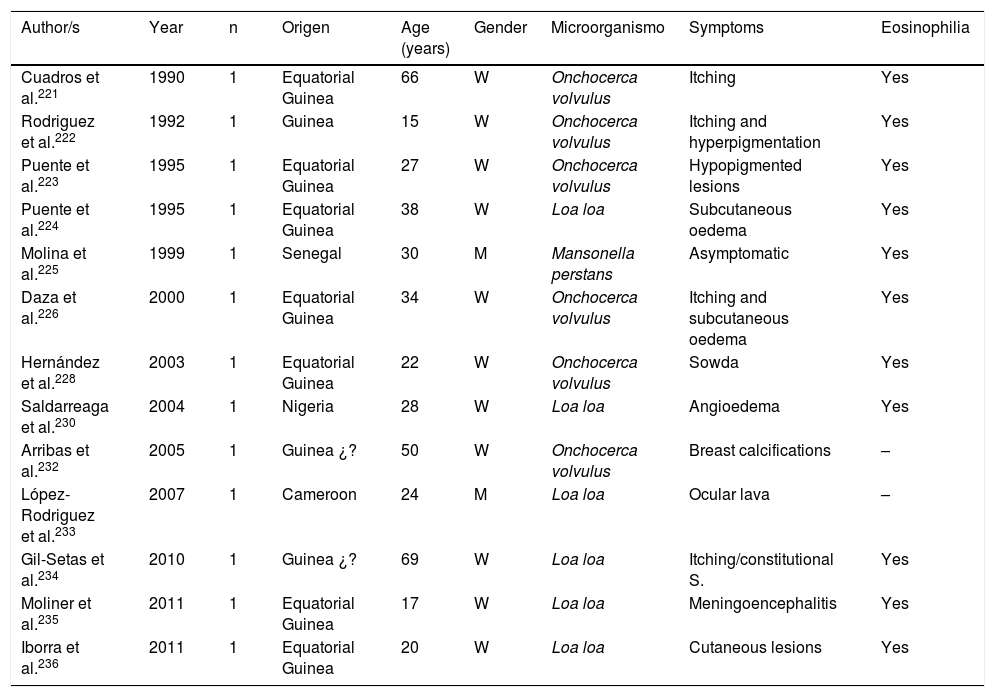

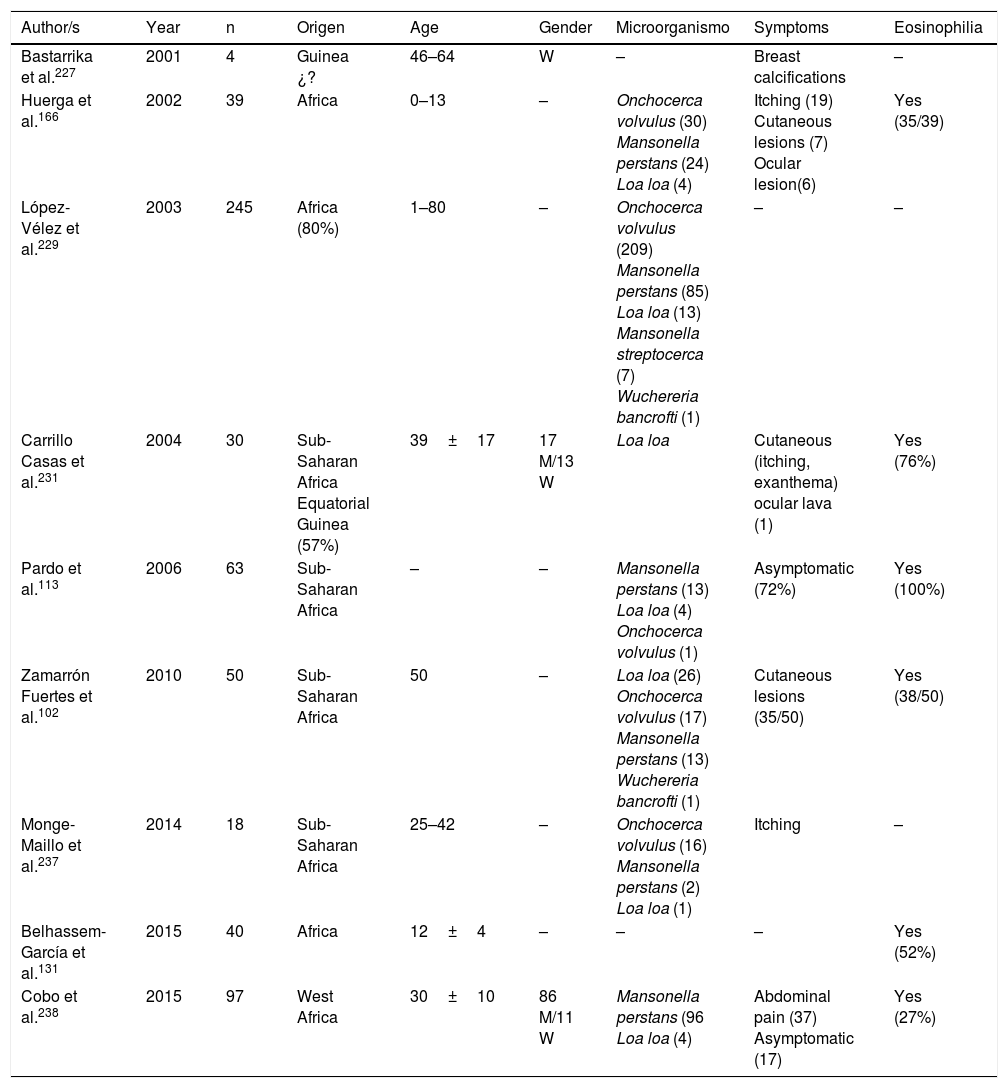

Filariasis associated with the presence of microfilariae in blood or tissues are in all cases imported diseases in Spain.102,113,131,166,221–238 Practically all of them are described in African patients, particularly sub-Saharan and with a clear predominance in West Africa (mainly Equatorial Guinea). The imported cases correspond mainly to immigrants, although they have also been described in travellers.102,237 Analysis of published cases (Tables 11 and 12) does not show any significant differences in the age of detection (1–80 years) or gender of patients. The 3 main imported filariasis are mansonelosis by Mansonella perstans, loaosis by Loa loa and oncocercosis by Onchocerca volvulus. Detection of Wuchereria bancrofti and Mansonella streptocerca is anecdotal,229 and there are no published case of infections by Brugia malayi, Brugia timori or Mansonella ozzardi. These data are subject to complexity in the diagnosis of these nematodes. Direct parasitological studies (blood smears and/or Knott test for the detection of microfilaremia, or “cutaneous pinching” in infection by O. volvulus and M. streptocerca) are very specific, but present limited sensitivity. Moreover, serological technique are very sensitive but have inherent limitations (e.g. cross over reactions with other helminths, no differentiation between active and past infections, etc.). In fact, the use of molecular biological techniques enables the detection of a large number of cases of undiagnosed loaosis from standard techniques.239,240 Furthermore, temporary evolution of imported filariasis presents a clear pattern, with a progressively lower number of cases of oncocercosis (very possibly related to control measures ing endemic countries, such as Equatorial Guinea) and a progressively lower number of case of mansonelosis (possibly linked to the screening of these entities in immigrants). Clinical symptoms are highly variables, with a large number of cases being asymptomatic. In symptomatic cases, common signs of these nematodes are: cutaneous (e.g. itching, exanthema, nodules) and ocular. It is therefore of interest to point out the presence of atypical manifestations, such as breast calcifications.227,232 The present of eosinophilia is very common, although its absence does not exclude diagnosis.

Imported Filariasis in Spain (cases).

| Author/s | Year | n | Origen | Age (years) | Gender | Microorganismo | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuadros et al.221 | 1990 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 66 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Itching | Yes |

| Rodriguez et al.222 | 1992 | 1 | Guinea | 15 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Itching and hyperpigmentation | Yes |

| Puente et al.223 | 1995 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 27 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Hypopigmented lesions | Yes |

| Puente et al.224 | 1995 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 38 | W | Loa loa | Subcutaneous oedema | Yes |

| Molina et al.225 | 1999 | 1 | Senegal | 30 | M | Mansonella perstans | Asymptomatic | Yes |

| Daza et al.226 | 2000 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 34 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Itching and subcutaneous oedema | Yes |

| Hernández et al.228 | 2003 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 22 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Sowda | Yes |

| Saldarreaga et al.230 | 2004 | 1 | Nigeria | 28 | W | Loa loa | Angioedema | Yes |

| Arribas et al.232 | 2005 | 1 | Guinea ¿? | 50 | W | Onchocerca volvulus | Breast calcifications | – |

| López-Rodriguez et al.233 | 2007 | 1 | Cameroon | 24 | M | Loa loa | Ocular lava | – |

| Gil-Setas et al.234 | 2010 | 1 | Guinea ¿? | 69 | W | Loa loa | Itching/constitutional S. | Yes |

| Moliner et al.235 | 2011 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 17 | W | Loa loa | Meningoencephalitis | Yes |

| Iborra et al.236 | 2011 | 1 | Equatorial Guinea | 20 | W | Loa loa | Cutaneous lesions | Yes |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

Imported filariasis in Spain (series).

| Author/s | Year | n | Origen | Age | Gender | Microorganismo | Symptoms | Eosinophilia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bastarrika et al.227 | 2001 | 4 | Guinea ¿? | 46–64 | W | – | Breast calcifications | – |

| Huerga et al.166 | 2002 | 39 | Africa | 0–13 | – | Onchocerca volvulus (30) Mansonella perstans (24) Loa loa (4) | Itching (19) Cutaneous lesions (7) Ocular lesion(6) | Yes (35/39) |

| López-Vélez et al.229 | 2003 | 245 | Africa (80%) | 1–80 | – | Onchocerca volvulus (209) Mansonella perstans (85) Loa loa (13) Mansonella streptocerca (7) Wuchereria bancrofti (1) | – | – |

| Carrillo Casas et al.231 | 2004 | 30 | Sub-Saharan Africa Equatorial Guinea (57%) | 39±17 | 17 M/13 W | Loa loa | Cutaneous (itching, exanthema) ocular lava (1) | Yes (76%) |

| Pardo et al.113 | 2006 | 63 | Sub-Saharan Africa | – | – | Mansonella perstans (13) Loa loa (4) Onchocerca volvulus (1) | Asymptomatic (72%) | Yes (100%) |

| Zamarrón Fuertes et al.102 | 2010 | 50 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 50 | – | Loa loa (26) Onchocerca volvulus (17) Mansonella perstans (13) Wuchereria bancrofti (1) | Cutaneous lesions (35/50) | Yes (38/50) |

| Monge-Maillo et al.237 | 2014 | 18 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 25–42 | – | Onchocerca volvulus (16) Mansonella perstans (2) Loa loa (1) | Itching | – |

| Belhassem-García et al.131 | 2015 | 40 | Africa | 12±4 | – | – | – | Yes (52%) |

| Cobo et al.238 | 2015 | 97 | West Africa | 30±10 | 86 M/11 W | Mansonella perstans (96 Loa loa (4) | Abdominal pain (37) Asymptomatic (17) | Yes (27%) |

W: woman; M: man; –: no data.

The 4 main tissue nematodosis reported in Spain are: triquinelosis, anisakidosis, toxocarosis and gnatosthomosis.

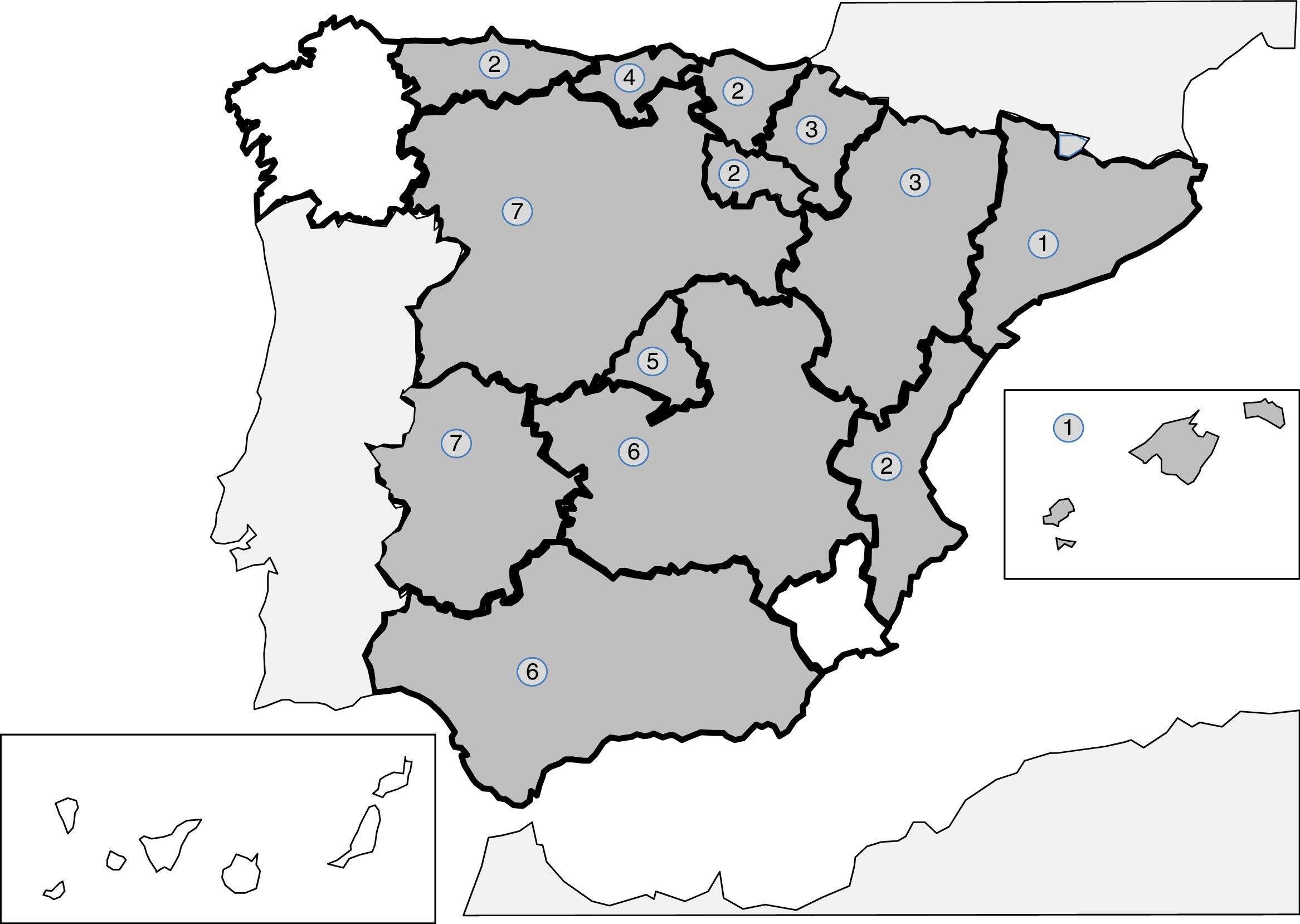

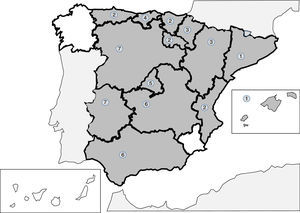

Infections produced by tissue nematodes of the genus Trichinella are autochthonous parasites, well referenced in the Spanish literature and in exceptional cases as an imported pathology.241–256 The 2 main species involved in the clinical cases described in Spain are Trichinella spiralis and Trichinella britovi. The common form of contagion is ingestion of raw meat or not well cooked meant of infected pigs and wild boar, which implies that the cases published are grouped around outbreaks. After the control of the domestic cycle in Spain (pigs), wild animals, like wild boars, have been the origin for most of the recent outbreaks. In any case, the rate of cases of this parasitism is increasingly lower, probably due to veterinary surveillance prior to consumption of game. The main outbreaks (indicated in Fig. 2) are concentrated on mountainous areas: (1) Cantabrian and Pyrenean mountain ranges; (2) Iberian range; (3) Central range; (4) Toledo mountain range and (5) Baetic rangea. During the last 25 years no autochthonous cases have been reported in Galicia, Murcia or the Canary island community. Clinical symptoms of the disease come from the tissue invasion of the parasite and the immunological response this triggers. The acute forms include, in variable proportions in each outbreak, the following data: myalgias, fever, exanthema, diarrhoea and palpebral oedema. Atypical forms have also been described, such as thoracic muscle calcification.254 Eosinophilia and the raising of quinase creatinine are common lab data in the described cases.

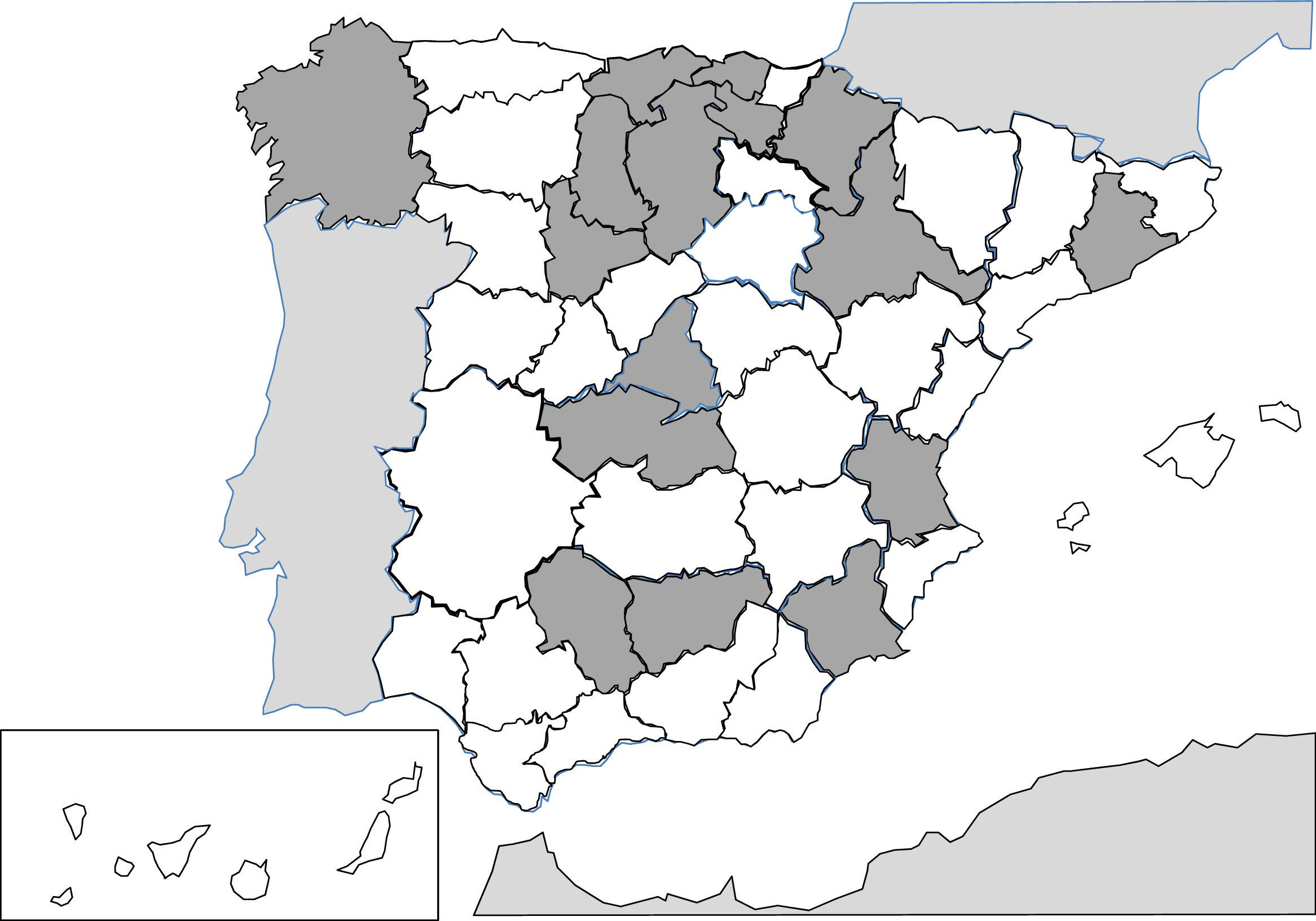

Since 1991, the description of isolated cases and clinical series of anisakis has been constant in Spain.257–287 Humans are infected by ingestion of fresh, raw or little cooked fish (e.g. by microwaves268), with the most common epidemiological background being the consumption of anchovies and in some cases, cebiche.284 Practically all cases correspond to acquired autochthonous infections and are mainly reported by autonomous communities, in the central area of the peninsula (Fig. 3). The most common agents are nematodes of the genus Anisakis (particularly Anisakis simplex) and to a lesser extent Pseudoterranova decipiens.258 The pathological consequences of the infection by these nematodes is apparent in3 different patterns: digestive, allergic or mixed. The digestive forms may affect several parts of the same, leading to compromise of the gastroduodenal region,ileal region, caecum and colon. Clinical symptoms depend on 2 complementary mechanisms: direct aggression by the nematode and the response of local hypsensitivity to the same. In the upper digestive tract the most common signs are acute epigastric pain after the intake of fish, frequently associated with allergic symptoms. However, when the lower digestive tracts involved abdominal pain presents with characteristics which are indistinguishable from an acute appendicitis or intestinal obstruction. Other atypical manifestations have also been described, such as splenic rupture286 or the appearance of an abdominal mass.271 Allergic signs are highly variables, both in their association with intestinal symptoms, and in their severity (from simple cutaneous forms to anaphylaxis).260,261,284 Other uncommon signs of hypersensitivity to these nematodes, described in Spain, are the appearance of a nephrotic syndrome281 and gingivoestomatitis.277 Eosinophilia is an inconstant finding in this parasitism (4–41%), and it depends on the before-mentioned clinical forms.

Data on toxocarosis, produced by Toxocara spp. are scarce in Spain and complex to interpret.287–295 The studies on seroprevalence of this infection, conducted in the nineties in several areas of the country, show a high rate of positivity, with figures of up to 66% in children from low socio-economic classes in Guipúzcoa, 3.4% in the general population of the Canary Island Community and between 17% and 32% in Galicia.288,292 These data should be further studied, since the etiological diagnosis of toxocarosis is based on serology, which displays cross-over reactivity with other nematodes such as Anisakis spp.294 The few reported clinical cases of toxocarosis correspond to both imported and autochthonous forms295 and within the latter, to ocular toxocarosis290 and visceral larva migrans.289 In the cases with visceral manifestations the presence of eosinophilia is common.291

Finally, gnathostomosis, mainly produced by Gnathostoma spinigerum, is a rare tissue nematodosis, but occasionally reported in Spain.296–300 This helminthosis appears as a consequence of food consumption (e.g. raw fish, frogs, snakes) and usually the sign are cutaneous lesions (similar to the cutaneous lava migrans) and in severe cases, myeloradiculitis or a radiculomyelo-meningoencephalitis.298,299 In general, it is a disease which is imported after travelling to Latin America297,298 and Asia (South East Asia and China),297,298,300 although 2 autochthonous cases have also been diagnosed in women from Granada who had not travelled to the tropics.296

ConclusionsTo conclude, helminthosis (autochthonous or imported, in travellers or immigrants, with or without immunosuppression) is a major problem in the Spanish population, both with regards to its prevalence and medical consequences. Association with eosinophilia (absolute or relative) presents great variability and is dependent upon a number of factors. For this reason, knowledge of the current situation may help etiological diagnosis of helminthosis. An appropriate therapeutic approach is required, with the avoidance of “empirical” attitudes that may be unsatisfactory, inappropriate or even harmful.301

FinancingThe authors declare they have not received any financing for carrying out this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Carranza-Rodríguez C, Escamilla-González M, Fuentes-Corripio I, Perteguer-Prieto M-J, Gárate-Ormaechea T, Pérez-Arellano J-L. Helmintosis y eosinofilia en España (1990–2015). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:120–136.