Cryptosporidium is the most common diarrhoea-causing protozoan parasite globally. Cryptosporidium infections primarily affect children aged <24 months in the sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where three out of four reported cases were due to C. hominis.1 Based on sequence analysis of the 60-kDa glycoprotein (GP60) gene, C. hominis has been demonstrated to comprise nine (Ia-Ik) subtype families with marked differences in geographical distribution.2,3

In middle August 2018 two Spanish-borne siblings complaining of gastrointestinal symptoms (a 2 years-old boy and a 12-years old girl) from a Nigerian family were attended at the María Jesús Hereza primary health centre (Leganés, Madrid). Both children had just returned from a 2-month family trip to Nigeria, where acute, non-bloody watery diarrhoea initiated. Three consecutive, soft stool specimens were obtained from each patient and submitted to the Microbiology Service of the University Hospital Severo Ochoa (Leganés, Madrid) for routine coproparasitological investigation including copro-culture and a commercially available solid phase qualitative immunochromatographic test for giardiosis/cryptosporidiosis (X/Pect Giardia/Cryptosporidium, Santa Fe, USA). Copro-cultures were negative but all six samples tested positive to Cryptosporidium by the rapid screening test. No microscopic examination was conducted. Pooled aliquots of the stool samples were shipped to the Spanish National Centre for Microbiology at Majadahonda (Madrid) for diagnosis confirmation and genotyping analyses. Genomic DNA was extracted and purified using the QIAamp® DNA stool mini test kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Molecular detection and characterisation of the samples was achieved by PCR amplification of the GP60 marker.4 Amplicons of the expected size (∼870bp) were directly submitted for sequencing. Sequence analyses confirmed the presence in both samples of C. hominis IbA13G3, a very rare subtype not previously reported in Spain to date. A representative nucleotide sequence of the subtype obtained was submitted to the GenBank® public repository under the accession number MK105902. Duration of gastrointestinal complaints lasted for two weeks after diagnosis and remitted spontaneously without specific treatment.

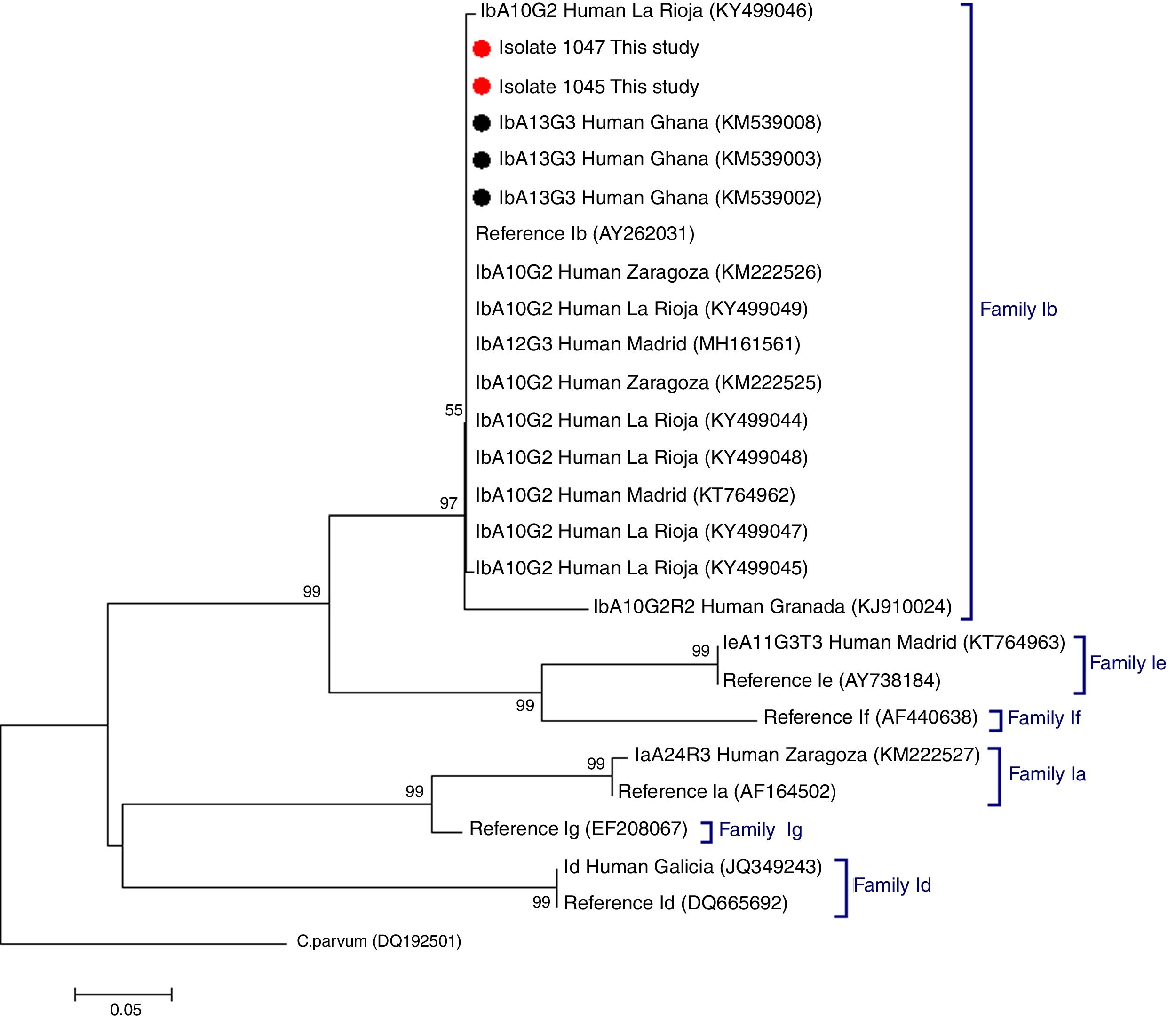

C. hominis IbA13G3 was initially reported in four Peruvian HIV-positive individuals in 2007.5 Subsequent molecular epidemiological surveys conducted in Nigeria allowed the identification of this subtype in community (n=7)6 and clinical (n=1)7 paediatric populations, and in HIV-infected persons (n=2).8 Additionally, the IbA13G3 subtype accounted for 19% (n=17) of all Cryptosporidium genetic variants detected in children from rural Ghana, only second after the IIcA5G3a subtype.9 Based on these molecular data a West African origin for C. hominis IbA13G3 has been suggested, but not conclusively proven, by some authors.5,7 As expected, our phylogenetic analysis based on the GP60 gene demonstrated that the IbA13G3 sequences generated in the present study and those available at GenBank from Ghana9 clustered together in a well-defined group within the family subtype Ib. In order to enable direct comparison, reference sequences and representative sequences of the most frequent C. hominis family subtypes circulating in different Spanish human populations were also included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic tree depicting evolutionary relationships among C. hominis IbA13G3 sequences at GP60 from human isolates generated in the present study (represented by red filled circles) and other available surveys (represented by black filled circles). Representative sequences of C. hominis subtype families previously identified in different Spanish regions were also included in the analysis for comparative purposes. The analysis was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. Bootstrapping values over 50% from 1.000 replicates are shown at the branch points. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter method. The rate variation among sites was modelled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter=2). C. parvum was used as outgroup taxa.

In summary, we identified the presence of C. hominis IbA13G3 in two returning travellers from Nigeria, the geographical area where this Cryptosporidium subtype seems more prevalent. To the best of our knowledge the IbA13G3 subtype has been only detected so far in West African countries and Peru, so this is the first report of the occurrence of this Cryptosporidium subtype in Europe. These and previous10,11 findings by our laboratory highlight the relevance of conducting active, molecular-based surveillance for the investigation of travel-related morbidity as an essential component of global public health surveillance.

FundingThis study was funded by the Health Institute Carlos III (ISCIII), Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness under project MPY 1350/16.

Competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The authors thank Marta Hernández de Mingo for excellent technical assistance, and Dr. Nelida Rosa Caya Tineo for providing relevant epidemiological and clinical information.