To describe an outbreak of imipenem-resistant metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, enzyme type bla, by horizontal transmission in patients admitted to a mixed adult ICU.

MethodsA case-control study was carried out, including 47 patients (cases) and 122 patients (control) admitted to the mixed ICU of a university hospital in Minas Gerais, Brazil from November 2003 to July 2005. The infection site, risk factors, mortality, antibiotic susceptibility, metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) production, enzyme type, and clonal diversity were analyzed.

ResultsA temporal/spatial relationship was detected in most patients (94%), overall mortality was 55.3%, and pneumonia was the predominant infection (85%). The majority of isolates (95%) were resistant to imipenem and other antibiotics, except for polymyxin, and showed MBL production (76.7%). Only bla SPM-1 (33%) was identified in the 15 specimens analyzed. In addition, 4 clones were identified, with a predominance of clone A (61.5%) and B (23.1%). On multivariate analysis, advanced age, mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, and previous imipenem use were significant risk factors for imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa infection.

ConclusionsClonal dissemination of MBL-producing P. aeruginosa strains with a spatial/temporal relationship disclosed problems in the practice of hospital infection control, low adherence to hand hygiene, and empirical antibiotic use.

Describir un brote causado por Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistente a imipenem productora de metallo-β-lactamasa (MBL), tipo de bla de la enzima, con transmisión horizontal de la muestra epidémica en pacientes ingresados en una unidad de cuidados intensivos para adultos mixta.

MétodosDurante el período comprendido entre noviembre de 2003 y julio de 2005, se realizó un estudio de casos y controles en el que se incluyó a 47 (casos) y 122 (control) pacientes en una unidad de cuidados intensivos para adultos mixta, de un hospital universitario de Uberlândia (Minas Gerais [Brasil]). Se analizaron los sitios de la infección, los factores de riesgo, la mortalidad total, la susceptibilidad a los antibióticos, la producción del tipo MBL, de la enzima y de la diversidad clonal.

ResultadosEn la mayoría de los pacientes (94%) se detectó una relación temporal/espacial. El índice de mortalidad total fue del 55,3% y la neumonía era la infección predominante (85%). La mayoría de las cepas (95%) era resistente a imipenem y a otros antibióticos, excepto al polimixin y la producción de MBL (76,7%). Únicamente se identificó blaSPM−1 en los 15 especímenes analizados. Además, se detectaron 4 clones, con predominio del clon A (61,5%) y B (23,1%). En análisis multivariados, la vejez, la ventilación mecánica, la traqueotomía y el uso previo del carbapenem son factores de riesgo significativos para el desarrollo de la infección de P. aeruginosa resistente a imipenem.

ConclusionesLa diseminación clonal de cepas de P. aeruginosa productora de MBL entre los pacientes con una relación temporal/espacial mostró problemas en el control de la infección del hospital, probablemente relacionado con una adherencia baja a la higiene de las manos y el uso empírico de los antibióticos.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause severe invasive disease in critically ill and immunocompromised patients.1 This microorganism is an important cause of nosocomial infections, including pneumonia, wound infections, bacteremia, and urinary tract infection,2,3P. aeruginosa is frequent cause of ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units (ICUs), the associated risk factors being mechanical ventilation lasting longer than 7 days, severity of the underlying condition, and previous antibiotic treatment, surgery, or immunosuppression.3,4

P. aeruginosa is a uniquely problematic microorganism because of a combination of inherent resistance to many drug classes and an ability to acquire resistance to all relevant treatments.5 Thus, carbapenems remain one of the best therapy options, although their use is threatened by the emergence of carbapenem-hydrolyzing, enzyme-producing strains and dissemination of multidrug-resistant clones. One reported outbreak of P. aeruginosa was only susceptible to polymyxin.6,7 In Brazilian hospitals, P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of nosocomial infection and the first cause of nosocomial pneumonia, notably in ICUs.8–10

This study describes a nosocomial outbreak of imipenem-resistant, metallo-β-lactamase-producing P. aeruginosa with horizontal transmission in patients hospitalized in a mixed ICU.

MethodsHospitalThe Uberlândia University Hospital is a 500-bed, tertiary-care teaching hospital in the city of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, with a 15-bed, mixed (surgical-clinical) adult ICU.

Study designFrom November 2003 to June 2005, a case-control study was carried out to investigate an imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa nosocomial outbreak, affecting 47 patients.

The index case was a 77-year-old woman with a diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism, who had received cefepime, ceftriaxone, and ampicillin antibiotic treatment in the ICU of another Uberlandia hospital in November 2003. She was referred to the ICU of the university hospital with a clinical diagnosis of respiratory failure and acute abdomen. Forty-eight hours after starting mechanical ventilation, ventilator-associated pneumonia due to P. aeruginosa resistant to imipenem and other antimicrobial classes was detected (isolate 1). The patient remained in the unit for approximately 3 weeks. She received imipenem treatment for 24 hours, and was then switched to polymyxin B® for 30 days’ time; despite this treatment, she died.

The risk factors associated with infection by imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (IRPa) were evaluated in a case-control study. Cases were defined as patients for whom culture had identified at least one IRPa strain (n=47). For each case, 2 or 3 controls were selected (n=122), defined as patients without IRPa infection, whose hospital stay coincided the closest in time with that of the infected patient. Only the first isolate per patient was considered for the analysis. During the study period, contamination of the health staff's hands (23), patients hospitalized during this period (86), and the surfaces in the ICU near the patients (mechanical ventilation unit, headboard, sinks) was investigated. The Institutional Ethics Committee gave their approval to conduct the study (CEP no186/2005).

Data collectionData for each patient were collected from the medical charts. The following variables were analyzed: age, sex, duration of ICU stay, comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, AIDS, renal failure, immunosuppression, cardiovascular disease), surgery, invasive device use (mechanical ventilation, central venous catheter, nasogastric tube) and prior use of antimicrobial drugs.

Identification and susceptibility testing proceduresBacterial strains were identified by conventional biochemical tests, as described elsewhere.11 Susceptibility testing was performed by agar diffusion with the following antimicrobials agents (CECON®): aztreonam (30μg), ciprofloxacin (5μg), cefepime (30μg), imipenem (10μg), meropenem (10μg), ceftazidime (30μg), gentamicin (10μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10μg), and polymyxin B (300U); the interpretative criteria used were those described in the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines.12 Quality control was conducted using P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. P. aeruginosa was defined as being multidrug-resistant when the organism was resistant to imipenem/meropenem and 2 or more of the other antimicrobial classes studied, except polymyxin.

Phenotypic metallo-β-lactamase productionAll strains resistant to ceftazidime and/or imipenem were screened for metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) production by the disk approximation test, using filter disks with ceftazidime (30μg) and imipenem (10μg) at 25mm or 10mm equidistant, respectively, and disks containing the following inhibitors: 2μL of undiluted 2-mercaptopropionic acid (2-MPA) solution (Aldrich Chemical Co, Milwaukee, USA) or 5μL of EDTA 500mM solution, as described by Arakawa.13 The positive control strain was an IMP-1-producing P. aeruginosa (PSA 319).14

Detection of the bla geneBecause of cost constraints, 15 MBL-positive isolates were selected as representative strains for the detection of genes encoding Ambler class B β-lactamase of the VIM, IMP, or SPM type by PCR using the following specific primers (reading 5′-3′): vim forward, GTCTATTTGACCGCGTC, vim reverse; CTACTCAACGACTGAGCG; imp forward, ATGAGCAAGTTATCTGTATTC, imp reverse: GTCGCAACGACTGTGTAG and spm reverse: TCGCCGTGTCCAGGTATAAC, spm forward: CCTACAATCTAACGGCGACC. The cycling parameters were 95°C for 5min, followed by 30 denaturation cycles at 95°C for 1min, annealing at 40°C for 1min, and extension at 68°C for 1min. PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels stained with 1% ethidium bromide.14,15

Genotyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresisAmong 47 IRPa isolates, 15 randomly selected isolates with a positive MBL-producing phenotype were typed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), as described by Denton et al,16 with modifications. Each plug was digested with 30U of SpeI restriction endonuclease (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 12h. Briefly, electrophoresis was performed by a 1% PFGE agarose gel run on the Gene Navigator (Pharmacia, Amersham Biociences) instrument at 164V for 20.1h, at 14°C. The equipment was adjusted for a pulse of 5s for 20h and 15s for 0.1h. Band patterns were visualized by ethidium bromide staining and ultraviolet transillumination. Cloning was evaluated according to the Tenover criteria,17 based on visual comparisons of the band patterns of samples run together in the same gel. Genetic similarities in samples were analyzed with a multivariate statistical package (MVSP 3.0).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were assessed with the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test; significance was set at a P value of ⩽0.05. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated with Epi-Info software, version 5.0. Variables were selected by forward logistic regression for the multivariate analysis.

ResultsFollowing the index case, 46 additional cases of hospital-acquired infection were documented, including mechanical ventilation-associated pneumonia (41), bloodstream infection (3), surgical wound infection (1) and urinary tract infection (1) caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to imipenem and other antimicrobial agents, including cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones (data not shown).

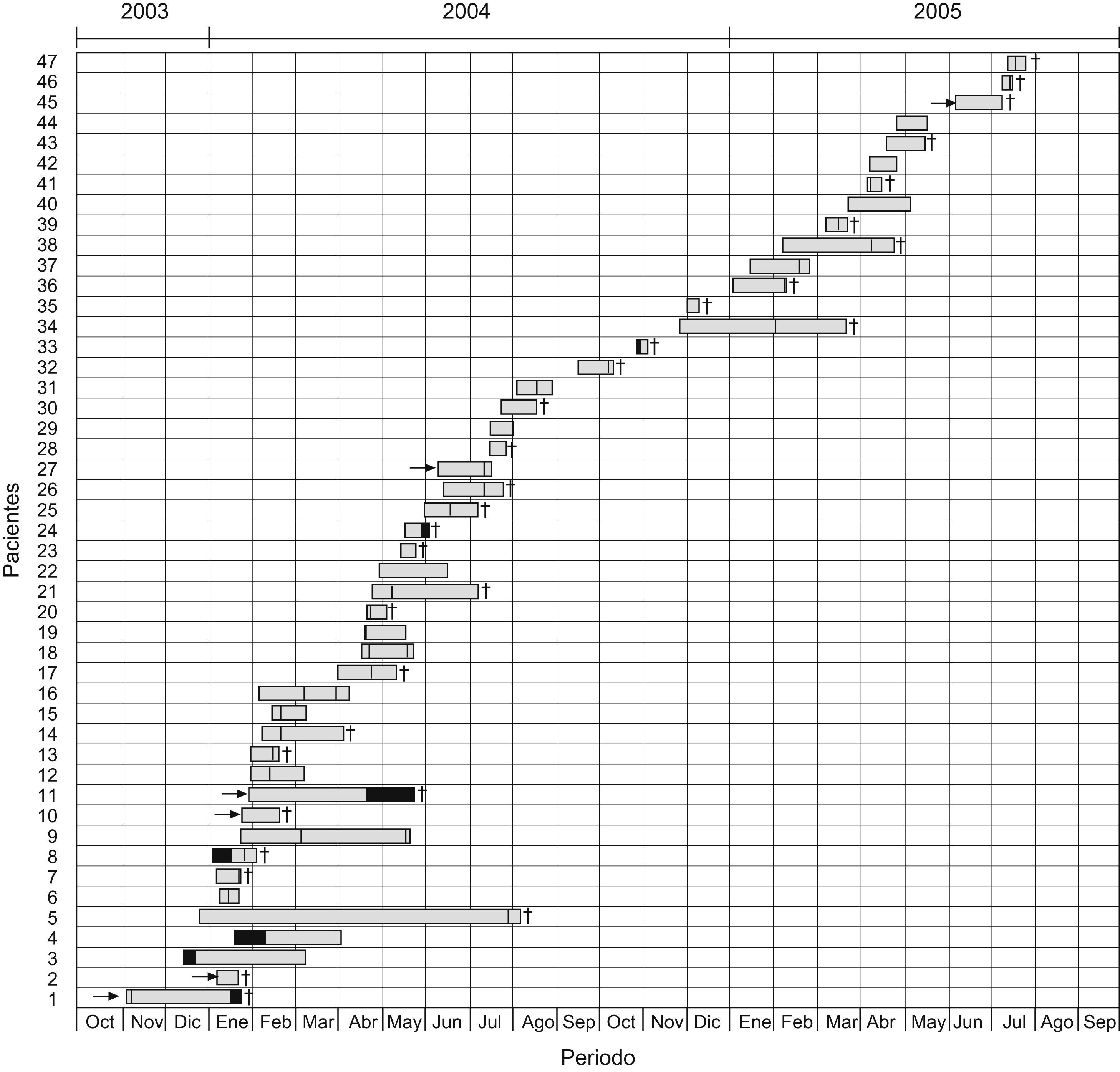

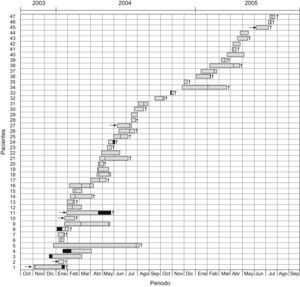

Fig. 1 shows the mortality data and the temporal/spatial relationships (ICU stay) among the 47 patients, which provides evidence of cross-transmission of IRPa.

Schematic representation of temporal and spatial relationships among patients infected with imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa during the study period. The arrows represent referral of patients from other hospitals to the ICU in Uberlandia Federal University Hospital, black sections indicate the time the patient was another ward, sections with hatched lines indicate time the patient was in the ICU and infected by imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, and crosses indicate death of the patient.

During the scrutiny for contamination, P. aeruginosa was not detected on culture of samples from the hands of 23 professionals, although initially this was suspected as the route by which the microorganism had been disseminated. However, P. aeruginosa was found colonizing 15/86 (17.4%) of the patients examined and on surfaces located near the patients, including the mechanical ventilation nebulizer in 10/86 (11.6%) and the headboard of the bed in 3/86 (3.5%), but not the sinks.

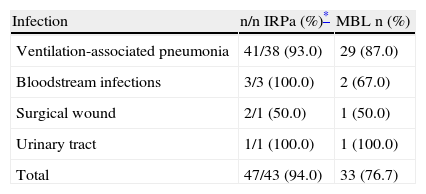

The majority of imipenem/ceftazidime-resistant P. aeruginosa strains in infected patients (33/43; 76.7%) had an MBL-positive phenotype, with no differences in detection between mercaptopropionic acid or EDTA (Table 1). In the contamination scrutiny, 17.8% (5/28) of P. aeruginosa imipenem/ceftazidime-resistant strains had an MBL-positive phenotype. Only 26.7% (4/15) of MBL-producing strains were positive for the blaSPM−1 gene. The blaVIM−2, bla IMP−1, and blaSPM genes were not found.

Infections by imipenem-resistant metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ICU patients at Uberlandia Federal University Hospital

| Infection | n/n IRPa (%)* | MBL n (%) |

| Ventilation-associated pneumonia | 41/38 (93.0) | 29 (87.0) |

| Bloodstream infections | 3/3 (100.0) | 2 (67.0) |

| Surgical wound | 2/1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Urinary tract | 1/1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Total | 47/43 (94.0) | 33 (76.7) |

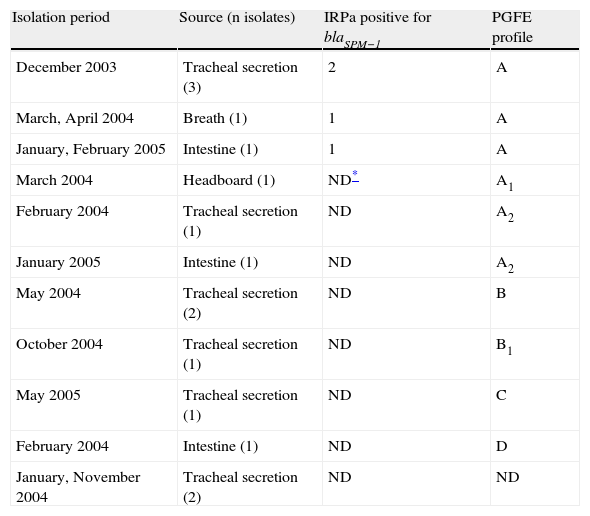

Two strains collected from the environment and strains from tracheal secretions were MBL-producers. A total of 15 strains were typed; however, 2 specimens remained undefined. Four clones and their subclones were found on PFGE, with a predominance of clone A, A1, A2 (61.5%), followed by B, B1 (23.1%), C and D (1 sample each), and 2 indeterminate results (Table 2).

Data on 15 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates at the Uberlandia Federal University Hospital ICU

| Isolation period | Source (n isolates) | IRPa positive for blaSPM−1 | PGFE profile |

| December 2003 | Tracheal secretion (3) | 2 | A |

| March, April 2004 | Breath (1) | 1 | A |

| January, February 2005 | Intestine (1) | 1 | A |

| March 2004 | Headboard (1) | ND* | A1 |

| February 2004 | Tracheal secretion (1) | ND | A2 |

| January 2005 | Intestine (1) | ND | A2 |

| May 2004 | Tracheal secretion (2) | ND | B |

| October 2004 | Tracheal secretion (1) | ND | B1 |

| May 2005 | Tracheal secretion (1) | ND | C |

| February 2004 | Intestine (1) | ND | D |

| January, November 2004 | Tracheal secretion (2) | ND | ND |

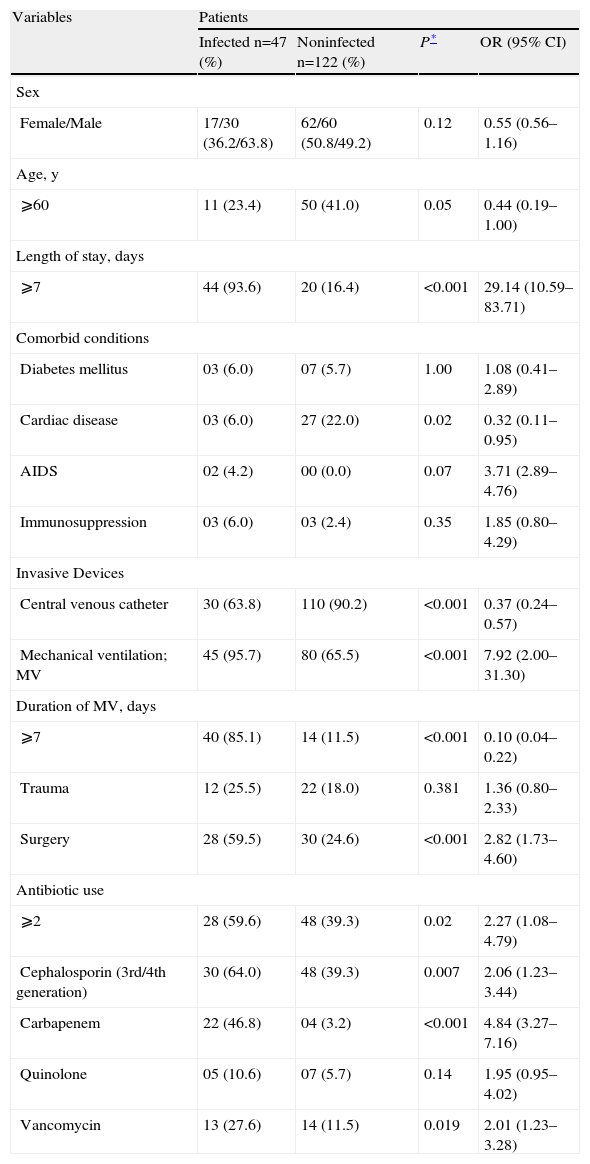

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, age ⩾60 years (P⩽0.02; OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.10–5.49), use of mechanical ventilation (P⩽0.001; OR 7.2; 95% CI 2.74–19.10), presence of a tracheotomy (P⩽0.02; OR 4.01; CI 1.17–13.72), and carbapenem use (P<0.001, OR 5.7; 95% CI 2.31–10.08) were risk factors for acquiring imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa infection

Univariate analysis of risk factors for nosocomial infection by resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ICU patients at Uberlandia Federal University Hospital

| Variables | Patients | |||

| Infected n=47 (%) | Noninfected n=122 (%) | P* | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female/Male | 17/30 (36.2/63.8) | 62/60 (50.8/49.2) | 0.12 | 0.55 (0.56–1.16) |

| Age, y | ||||

| ⩾60 | 11 (23.4) | 50 (41.0) | 0.05 | 0.44 (0.19–1.00) |

| Length of stay, days | ||||

| ⩾7 | 44 (93.6) | 20 (16.4) | <0.001 | 29.14 (10.59–83.71) |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 03 (6.0) | 07 (5.7) | 1.00 | 1.08 (0.41–2.89) |

| Cardiac disease | 03 (6.0) | 27 (22.0) | 0.02 | 0.32 (0.11–0.95) |

| AIDS | 02 (4.2) | 00 (0.0) | 0.07 | 3.71 (2.89–4.76) |

| Immunosuppression | 03 (6.0) | 03 (2.4) | 0.35 | 1.85 (0.80–4.29) |

| Invasive Devices | ||||

| Central venous catheter | 30 (63.8) | 110 (90.2) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.24–0.57) |

| Mechanical ventilation; MV | 45 (95.7) | 80 (65.5) | <0.001 | 7.92 (2.00–31.30) |

| Duration of MV, days | ||||

| ⩾7 | 40 (85.1) | 14 (11.5) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.04–0.22) |

| Trauma | 12 (25.5) | 22 (18.0) | 0.381 | 1.36 (0.80–2.33) |

| Surgery | 28 (59.5) | 30 (24.6) | <0.001 | 2.82 (1.73–4.60) |

| Antibiotic use | ||||

| ⩾2 | 28 (59.6) | 48 (39.3) | 0.02 | 2.27 (1.08–4.79) |

| Cephalosporin (3rd/4th generation) | 30 (64.0) | 48 (39.3) | 0.007 | 2.06 (1.23–3.44) |

| Carbapenem | 22 (46.8) | 04 (3.2) | <0.001 | 4.84 (3.27–7.16) |

| Quinolone | 05 (10.6) | 07 (5.7) | 0.14 | 1.95 (0.95–4.02) |

| Vancomycin | 13 (27.6) | 14 (11.5) | 0.019 | 2.01 (1.23–3.28) |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The presence of MBL-producing P. aeruginosa has been described in many hospitals around the world.18 Nonetheless, dissemination of an SPM-1 MBL-producing P. aeruginosa epidemic has been demonstrated only in hospitals of different Brazilian regions.8,14,19 As compared to other studies carried out in Brazil, the presently reported nosocomial outbreak of imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa infection involved the largest number of cases to date (47 patients) and was associated with 4 clones. This study is the first to include an expressive number (≈60%) of critical IRPa-infected patients who died within 30 days after the infection.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading pathogen in mechanical ventilation-associated nosocomial pneumonia, with an associated mortality rate of 20% to 80%.8,9,20 During the outbreak in our hospital, pneumonia was the predominant infection, accounting for more than two-thirds (85%) of the cases, followed by bloodstream infection and surgical wounds.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that patients with nosocomial IPRa infection were more likely to have been exposed to mechanical ventilation, and that tracheotomy and use of carbapenems were predisposing factors for the infection. These findings are consistent with those of other studies.4,20–22

Although the advent of carbapenems in the 1980s heralded a new treatment option for serious bacterial infections, carbapenem resistance is now observed in Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter spp., and is becoming commonplace in P. aeruginosa.18P. aeruginosa possessing MBLs has been increasingly reported worldwide, mainly in ICUs and including Brazil,14,18,19 but at rates comparatively lower than those found in our study (≈90%).

These enzymes are clinically relevant because of their ability to hydrolyze most β-lactams, including carbapenems (but excluding aztreonam),18 and their association with mobile genetic elements, increasing the possibility of rapid spread.19,23–25 In the Americas, 6 different MBLs have been described in P aeruginosa, including SPM-1, IMP-1, IMP-16, VIM-2, VIM-8 and VIM-1118 and three MBL types (SPM-1, VIM-2 and IMP-1) have been detected in Brazilian hospitals, with most strains expressing blaSPM−1, which is disseminated among our hospitals.8,14,19,22 We found that MBL-producing strains accounted for a substantial number of cases (76.7%), and that the strains were clinically relevant, because 70.0% of the patients died. In contrast to the reported results of Sader et al,26 neither blaIMP−1 or blaVIM−1 genes were found in this study.

The acquisition of resistant bacteria in hospitals may be a consequence of selective pressure exerted by the use of antibiotics and/or horizontal dissemination.27 Molecular typing of strains presenting the blaSPM−1 gene showed the presence of a single clone (A). In the present study, multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were clustered in two major genotypes; these showed coresistance to most of the antimicrobial agents tested. Multidrug resistance can be explained by the accumulation of several resistance mechanisms, including gene mutation, over-expression of efflux pumps, loss or modification of porins, and acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamases.28 This suggests that the selective pressure of previous antimicrobial use in the unit contributed to the emergence of resistant clones.

Both the SPM and non-SPM-infected patients were clustered for 18 months in a single unit, with overlapping during their hospitalization. These data suggest that horizontal transmission between these patients may have played a role in the dissemination of the infection. Clonal dissemination was detected within and between intensive care units in São Paulo (4) and Brasilia,10 but with unrelated strains recovered from one of them. These data differ from those of Pellegrino et al29 who reported clonal dissemination between private and public institutions in Rio de Janeiro, in which both presented an apparently endemic background.

Detection of clonal dissemination usually indicates inadequate nosocomial infection control practice.10 This outbreak of P. aeruginosa infection was probably linked to transmission of the microorganism via the hands of healthcare workers. We did not identify hand carriage among the workers examined, but a spatial/temporal relationship was seen among the cases in our unit, and low adherence (23%) to proper hand washing30 practice was detected in a recent study.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct an analysis using both classical and molecular techniques of an outbreak of infection associated with a highly prevalent MBL-producing P. aeruginosa, including mainly blaSPM−1 strains clustered in 2 major genotype, resulting in a significant increase in mortality of elderly patients and in previous use of antibiotics. The clonal dissemination among patients in our unit indicates problems in nosocomial infection control practice, likely associated with low adherence to hand hygiene, and selective pressure that provides resistant strains with an advantage over their susceptible ancestors.