A 37-year-old male HIV+ individual (CD4 cell nadir of 153 cells/mm3 and HIV-1 RNA viral load zenit of 9832 copies/mL), treated with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/efavirenz with poor therapeutic adherence and without medical follow up for the last 4 years was admitted to the emergency department with history of 3 days of left sided pleuritic chest pain, mild dyspnea and a temperature of 37.5°C. He was a daily consumer of amphetamines for 5 years and previously had received treatment for intestinal giardiasis and syphilis. Vital signs at arrival showed BP 110/70mmHg, temperature 37.5°C, heart rate 85bpm, respiratory rate 22, SpO2 96%. Physical examination revealed decreased breathing sounds over the left lung base. Rest was unremarkable.

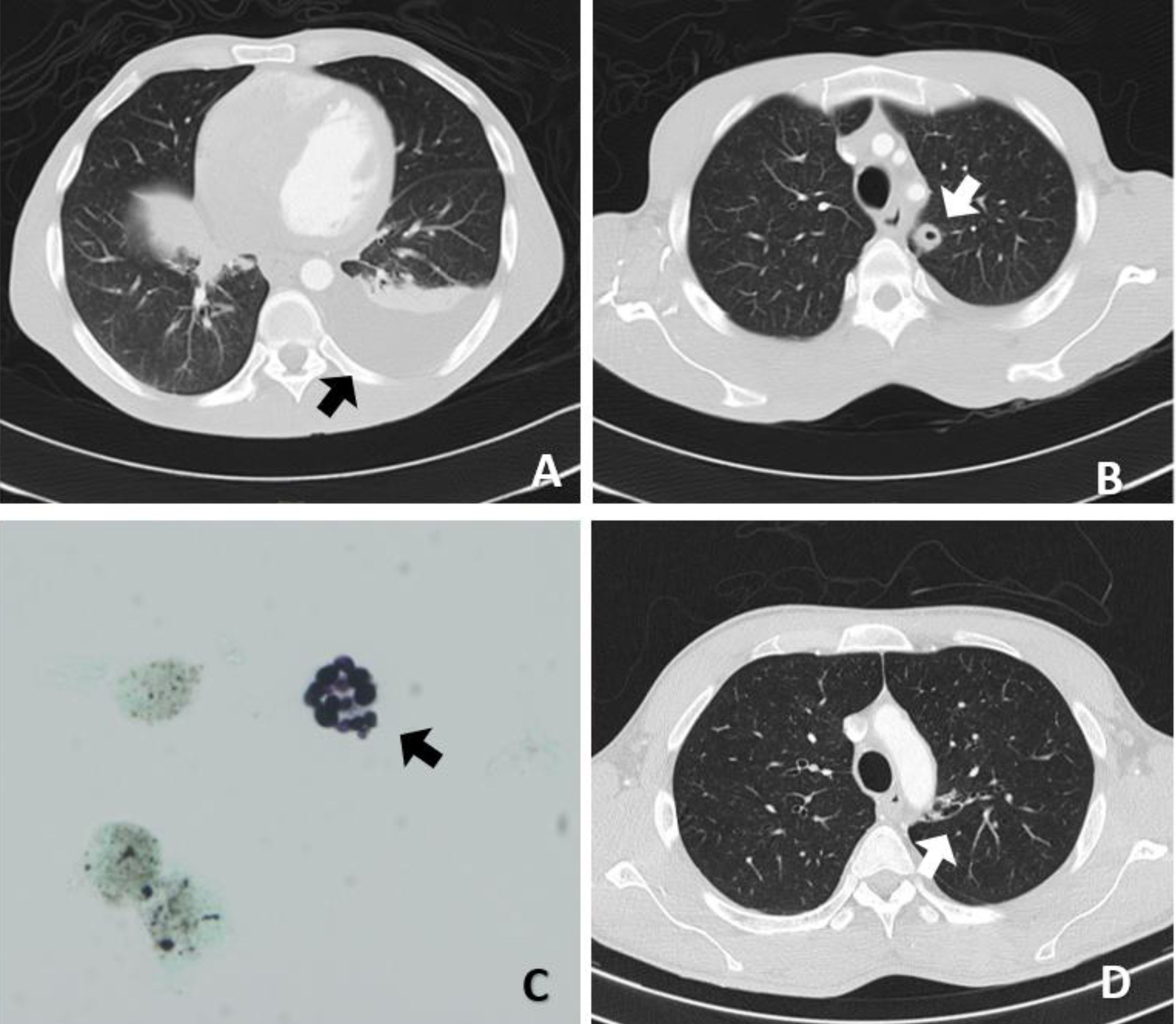

The laboratory findings showed a normocytic, normochromic anemia (Hemoglobin 11.7g/dl) with normal white blood count (WBC) and platelets, a normal renal and liver function and mild increase of C-reactive protein to 1.7mg/dl. HIV-1 RNA viral load was 122,000copies/mL and CD4+ T cell count 13cells/mm3. Chest X-ray showed a left costophrenic recess blunting and a left perihilar cavitary nodule. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed revealing moderate left pleural effusion with atelectasis, a thick-walled cavitary nodule in the left superior lobule, and left hilar calcified lymph nodes (Fig. 1A and B).

(A, B) Computed tomography scan showing a thick-walled cavitated nodule in the left superior lobe with ipsilateral pleural effusion. (C) Cryptococcus neoformans in bronchoalveolar lavage (silver staining, 600×). (D) Computed tomography scan showing a thin-walled cavitated lesion in the apical posterior segment with bronchial communication; no pleural effusion was found.

A thoracentesis was made, with positive lights criteria suggesting exudative effusion [proteins 52g/L, LDH 173U/L; serum values: proteins: 63g/L, LDH 166U/L, WBC: 3710cells/mm3 (49% neutrophils, 37% lymphocytes and 12% mesothelial cells) and adenosine deaminase (ADA) 51UI/L]. Pleural effusion culture was negative for bacteria. PCR detection for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pleural effusion was negative.

Serum Cryptococcus neoformans antigen (CrAg) was tested, detecting titers of 1/64. Treatment with amphotericin B and flucytosine was initiated. A lumbar puncture was practiced ruling out central nervous system infection, allowing treatment simplification to fluconazole in monotherapy. We initiated antiretroviral therapy with bictegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, and pneumocystis prophylaxis with trimethoprim – sulfamethoxazole.

Finally, C. neoformans isolation in pleural effusion culture provided the definitive diagnosis, exhibiting a strain with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) 8μg/ml for fluconazole and 0.06μg/ml for voriconazole. Based on these results, we switched treatment to voriconazole. The organism was detectable after 82h of incubation. Subsequently bronchoalveolar lavage was also positive for C. neoformans (Fig. 1C).

The patient showed clinical and laboratory improvement, being discharged to complete outpatient treatment with voriconazole and follow-up by the infectious disease department. Eight months after the diagnosis a thoracic CT scan was made, showing mainly a thin-walled cavitated lesion in the apical posterior segment with bronchial communication and resolution of the pleural effusion (Fig. 1D).

DiscussionCryptococcosis infection is caused mainly by C. neoformans, an opportunistic fungal infection that became worldwide relevant when the HIV era started.1,2 The most common clinical presentations include neurological and pulmonary involvement.3 Nevertheless, the cryptococcal pleural infection remains rare, with about 50 cases reported in the literature.4

In our patient, differential diagnosis based on cavitary pulmonary lesions and lymphocytic pleural effusion was made. Because cryptococcosis may also present an elevated ADA in pleural effusion, it can easily be misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, a far more common entity, and be initially treated with tuberculostatic therapy.5

Pleural effusion and bronchoalveolar lavage cultures lead to the definitive diagnosis. Pleural effusion cultures for Cryptococcus may be negative due to the small number of microorganisms in pleural fluid. It has been postulated that the release of the antigen is the responsible for a pleural inflammatory response that leads to pleural effusion rather than the microorganism by itself.4

Regarding the treatment, over the past decade there has been an increase in reports describing C. neoformans with increased MICs for fluconazole. Nowadays there is still no consensus on the cut-off point or its clinical relevance.6 Recent studies define MICs≤8μg/ml as susceptible, 16–32μg/ml as dose-dependent susceptible, and ≥64μg/ml as resistant.7 Nonetheless, the EUCAST guidelines state that the clinical breakpoint is not yet determined.8

In conclusion, atypical presentations of cryptococcus infections should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pleural effusion in HIV patients. Additional research is needed to define the relevance of the antifungal susceptibility in C. neoformans infection and its possible clinical implications.

FundingThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We thank Dr. Daniel Martinez from the Pathology Department, Thoracic Oncology Unit of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, for his contribution to our work.