Bloodstream infections are one of the healthcare-associated infections with the highest impact in terms of mortality and cost. Mortality is in the range of 10.1–18% in high-income nations.1–3 In the United States, the individual cost per bloodstream infection episode has been estimated at approximately US$45,814.4

Although infrequent, contamination of infusates still remains an important cause of bloodstream infections, especially in low- and middle-income countries.5 The most recent survey in Mexican hospitals revealed a 7.9% frequency of contaminated infusates, mostly due to Enterobacter spp.6

On 17/09/2019, four patients that had urological procedures earlier that same day in the Urology outpatient clinic of our hospital were hospitalized due to signs and symptoms of sepsis. An outbreak investigation ensued. Cases were defined as patients that had attended the clinic on 17/09/2019 and developed sepsis afterwards. The exposed population was defined as patients that attended the clinic that same day. Information regarding urological procedures as well as infection prevention and control procedures were obtained by review of electronic medical records and direct interaction with treating physicians. Since intravenous access was suspected to be the route of exposition, cultures were taken from propofol vials, alcohol pledgets and antiseptic solutions.

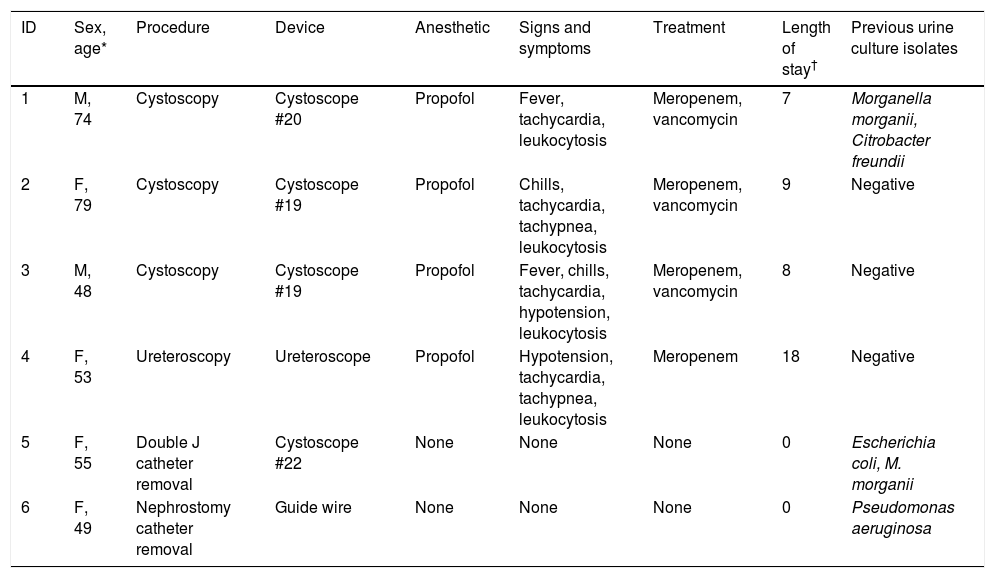

Six patients were treated in the clinic on 17/09/2019 and four fulfilled the case definition. Cases received broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. No microorganisms were recovered from blood and urine cultures. All cases made a full recovery. Two patients from the exposed population did not develop any signs or symptoms and were not admitted (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of cases and non-affected patients.

| ID | Sex, age* | Procedure | Device | Anesthetic | Signs and symptoms | Treatment | Length of stay† | Previous urine culture isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M, 74 | Cystoscopy | Cystoscope #20 | Propofol | Fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis | Meropenem, vancomycin | 7 | Morganella morganii, Citrobacter freundii |

| 2 | F, 79 | Cystoscopy | Cystoscope #19 | Propofol | Chills, tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis | Meropenem, vancomycin | 9 | Negative |

| 3 | M, 48 | Cystoscopy | Cystoscope #19 | Propofol | Fever, chills, tachycardia, hypotension, leukocytosis | Meropenem, vancomycin | 8 | Negative |

| 4 | F, 53 | Ureteroscopy | Ureteroscope | Propofol | Hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis | Meropenem | 18 | Negative |

| 5 | F, 55 | Double J catheter removal | Cystoscope #22 | None | None | None | 0 | Escherichia coli, M. morganii |

| 6 | F, 49 | Nephrostomy catheter removal | Guide wire | None | None | None | 0 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

ID, patient identifier; M, male; F, female.

Use of propofol was identified as the common denominator of cases (patients 1–4); none of the unaffected patients (5 and 6) had received propofol. The anesthesiologist present that day admitted to the reuse of propofol on 17/09/2019 due to a sudden shortage of this drug on that particular day. Briefly, propofol was extracted from their original vials in 10ml-sterile syringes; then, sterile saline solution containers were emptied and refilled with 100ml of propofol through the container hub using the syringes. The same containers were shared among the cases. Sterile needles were used for venous punction.

Pantoea agglomerans was recovered from the remains of one of the used propofol vials that was available for culture. After aseptic preparation of all propofol infusates was enforced, the outbreak was over.

This report stresses the importance of basic practices of infection prevention and control. Breaches in aseptic infusate practices have been described in outbreaks linked to propofol use as far back as 1990,7 however, deviations continue to be reported.8 Although a successful program for prevention of bloodstream infections has been in place in our hospital for more than a decade and has resulted in zero infections for prolonged periods of time (unpublished results), this is a remainder that surveillance must not be relaxed. Timely detection of the cause of the outbreak in our hospital led to swift actions that prevented further cases. Despite negative cultures in cases, causality is strongly suggested by the following facts: (1) the presence of a common source in cases and its absence in non-affected patients, (2) the rapid onset of symptoms after exposure to the common source by the intravenous route (endotoxin in the infusate could have been the triggering event9), (3) the evidence of a pathogen recovered from the common source, (4) the evidence of breaches in the aseptic preparation of propofol infusions, (5) the extinction of the outbreak after reuse of propofol was stopped, and (6) the absence of sepsis cases before manipulation of propofol vials occurred.

Propofol infusate contamination remains an important risk factor for sepsis and bloodstream infections when aseptic practices are not followed in anesthetic procedures. We make a call for continued surveillance and education to prevent further cases, especially in outpatient settings.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.