In the last years an increase in the anaerobes resistance has been worldwide reported1,2; however, most studies only refer to Bacteroides fragilis group and antibiotic susceptibility data of other genus are limited. Although reasons that may lead to failure of therapy include lack of surgical drainage or poor source control, as well as patient's comorbidities and poor penetration and low levels of antimicrobial at the site of infection, a correlation between the antimicrobial resistance of the anaerobic pathogens and poor clinical outcome has been reported.2

Routinely determining in vitro susceptibility is technically difficult, time-consuming and is not recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), but in our laboratory we perform it in all clinically relevant isolates. The aim of the study was to analyze the trends in the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of anaerobes isolated in our health area for the last 15 years.

Between January 2000 and December 2014, all clinically relevant anaerobes isolated in specimens collected from H.U.G.C. Doctor Negrín and C.H.U.I. Materno Infantil were included. Specimens were plated on BD™ Brucella Blood Agar with Hemin and Vitamin K1 (Becton, Dickinson and Company) and were incubated for 96h at 35°C in anaerobic atmosphere. Identification was carried out using the Rapid ID 32A® (bioMérieux) system and/or conventional biochemical methods. In vitro antibiotic susceptibility was performed by broth microdilution method, with the ATB™ ANA (bioMérieux) system or agar diffusion using E-test method (bioMérieux). In those specimens where growth of more than three microorganisms (mixed flora) was obtained, neither identification nor susceptibility tests were performed. Susceptibility profiles were determined according to the CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints. Susceptibility trends were analyzed by binary logistic regression with PASW Statistics 18.0 (IBM). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

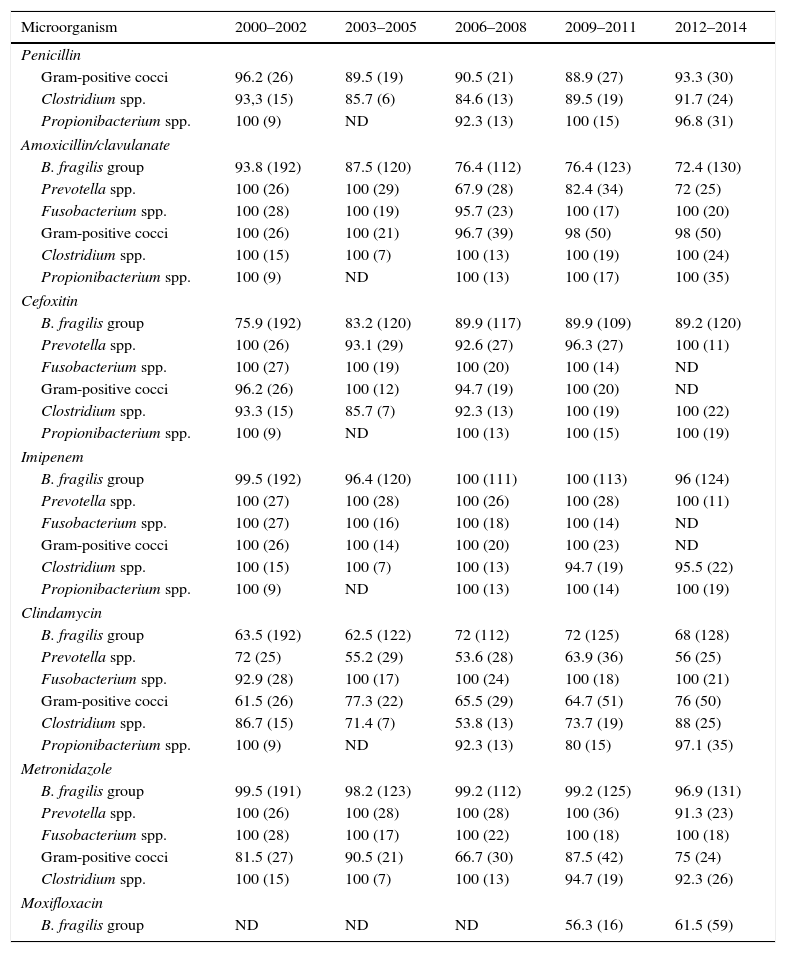

We included 1399 non-duplicated (one per patient) isolates recovered from 1348 specimens. The specimen sources were: abscesses (42.1%), blood (20.2%), skin and soft tissues (20%), cerebrospinal and other sterile body fluids (16.1%) and others (1.6%). In 56% of the specimens, only anaerobes were recovered. The distribution of isolates was: 685 (49%) B. fragilis group, 186 (13.3%) gram-positive cocci, 146 (10.4%) Prevotella spp., 115 (8.2%) Fusobacterium spp., 80 (5.7%) Clostridium spp., 79 (5.7%) Propionibacterium spp. and 108 (7.7%) others. Table 1 shows the percentage of susceptible isolates, grouped in five three year-periods, to each of the antimicrobial agent studied.

Percentage of susceptible isolates and number of strains included in each period of time (in brackets).

| Microorganism | 2000–2002 | 2003–2005 | 2006–2008 | 2009–2011 | 2012–2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | |||||

| Gram-positive cocci | 96.2 (26) | 89.5 (19) | 90.5 (21) | 88.9 (27) | 93.3 (30) |

| Clostridium spp. | 93,3 (15) | 85.7 (6) | 84.6 (13) | 89.5 (19) | 91.7 (24) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 100 (9) | ND | 92.3 (13) | 100 (15) | 96.8 (31) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | |||||

| B. fragilis group | 93.8 (192) | 87.5 (120) | 76.4 (112) | 76.4 (123) | 72.4 (130) |

| Prevotella spp. | 100 (26) | 100 (29) | 67.9 (28) | 82.4 (34) | 72 (25) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (28) | 100 (19) | 95.7 (23) | 100 (17) | 100 (20) |

| Gram-positive cocci | 100 (26) | 100 (21) | 96.7 (39) | 98 (50) | 98 (50) |

| Clostridium spp. | 100 (15) | 100 (7) | 100 (13) | 100 (19) | 100 (24) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 100 (9) | ND | 100 (13) | 100 (17) | 100 (35) |

| Cefoxitin | |||||

| B. fragilis group | 75.9 (192) | 83.2 (120) | 89.9 (117) | 89.9 (109) | 89.2 (120) |

| Prevotella spp. | 100 (26) | 93.1 (29) | 92.6 (27) | 96.3 (27) | 100 (11) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (27) | 100 (19) | 100 (20) | 100 (14) | ND |

| Gram-positive cocci | 96.2 (26) | 100 (12) | 94.7 (19) | 100 (20) | ND |

| Clostridium spp. | 93.3 (15) | 85.7 (7) | 92.3 (13) | 100 (19) | 100 (22) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 100 (9) | ND | 100 (13) | 100 (15) | 100 (19) |

| Imipenem | |||||

| B. fragilis group | 99.5 (192) | 96.4 (120) | 100 (111) | 100 (113) | 96 (124) |

| Prevotella spp. | 100 (27) | 100 (28) | 100 (26) | 100 (28) | 100 (11) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (27) | 100 (16) | 100 (18) | 100 (14) | ND |

| Gram-positive cocci | 100 (26) | 100 (14) | 100 (20) | 100 (23) | ND |

| Clostridium spp. | 100 (15) | 100 (7) | 100 (13) | 94.7 (19) | 95.5 (22) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 100 (9) | ND | 100 (13) | 100 (14) | 100 (19) |

| Clindamycin | |||||

| B. fragilis group | 63.5 (192) | 62.5 (122) | 72 (112) | 72 (125) | 68 (128) |

| Prevotella spp. | 72 (25) | 55.2 (29) | 53.6 (28) | 63.9 (36) | 56 (25) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 92.9 (28) | 100 (17) | 100 (24) | 100 (18) | 100 (21) |

| Gram-positive cocci | 61.5 (26) | 77.3 (22) | 65.5 (29) | 64.7 (51) | 76 (50) |

| Clostridium spp. | 86.7 (15) | 71.4 (7) | 53.8 (13) | 73.7 (19) | 88 (25) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 100 (9) | ND | 92.3 (13) | 80 (15) | 97.1 (35) |

| Metronidazole | |||||

| B. fragilis group | 99.5 (191) | 98.2 (123) | 99.2 (112) | 99.2 (125) | 96.9 (131) |

| Prevotella spp. | 100 (26) | 100 (28) | 100 (28) | 100 (36) | 91.3 (23) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (28) | 100 (17) | 100 (22) | 100 (18) | 100 (18) |

| Gram-positive cocci | 81.5 (27) | 90.5 (21) | 66.7 (30) | 87.5 (42) | 75 (24) |

| Clostridium spp. | 100 (15) | 100 (7) | 100 (13) | 94.7 (19) | 92.3 (26) |

| Moxifloxacin | |||||

| B. fragilis group | ND | ND | ND | 56.3 (16) | 61.5 (59) |

ND, no data available or less than five isolates.

Penicillin susceptibility for anaerobic gram-positive remains unchanged over the study period; however among anaerobic gram-negative bacteria, B. fragilis group and Prevotella spp. have significantly reduced their susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanate (P<0.05) as recently reported by several authors.2–7 By contrast, B. fragilis group susceptibility to cefoxitin has significantly increased (P<0.05). Other anaerobes have not undergone major changes in their susceptibility to cefoxitin. In our study, as well as others published elsewhere, imipenem resistant isolates are rare2−8 and we have only found 11 non-susceptible isolates of B. fragilis group (five from skin and soft tissues, three from blood cultures, one from peritoneal fluid) and two non-susceptible isolates of C. perfringens collected from blood and abdominal drainage.

Our results, consistent with previous studies,2,4–9 show a widespread decrease in the susceptibility to clindamycin, especially in B. fragilis group (P<0.05), but not negligible in Prevotella spp. and gram-positive cocci.

Unlike other authors,2,4–7,10 who communicate a low percentage of metronidazole non-susceptible isolates among anaerobes, we have found, like Novak et al., 10–25% of gram-positive cocci resistant to metronidazole.

B. fragilis group moxifloxacin susceptibility is somewhat lower than that reported by other authors5,6,8 limiting its usefulness as empirical treatment of polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections.

Multidrug-resistant B. fragilis group isolates (resistant to three or more different families of antimicrobials) are infrequently in Europe.7 During the study period we found four multidrug-resistant isolates that were collected from blood (1), peritoneal fluid (1) and surgical wound (2). Two isolates were resistant to amoxicillin/clavulanate, clindamycin and moxifloxacine, one isolate to amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefoxitin and clindamycin and one isolate to amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefoxitin and imipenem.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of anaerobes has consistently decreased over the past 15 years, so we consider necessary to determine in vitro susceptibility of anaerobes isolated in severe infections or, at least, monitor resistance patterns in order to establish an appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy, as susceptibility of anaerobes to antimicrobial treatments has become less predictable.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.