Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) is an extremely slow-growing and fastidious organism to culture, and it was not until the first polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was developed that its role as a pathogen in human disease was established. This sexually transmitted infection (STI) is a well-recognized cause of non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU).1,2

European treatment guidelines recommend azithromycin for the treatment of uncomplicated MG infection and moxifloxacin for uncomplicated macrolide-resistant MG infection.2

The rapid emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance in MG is a growing concern. Antimicrobial resistance rapidly spread to Europe, where the reported azithromycin resistance rate ranges from 20.1% to 35.6%, and mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance were found in 1.9–3.7% of MG infections.3,4

The established gold standard method for detection of mutations associated with antimicrobial resistance is Sanger sequencing of resistance-determining regions in the 23S rRNA and the parC genes. However, few commercial assays are available for this purpose. In this context, specimens from male and female patients with a suspected diagnosis of a STI from April 2019 to March 2021 were analyzed using a commercial real-time PCR assay for detection of mutations associated with azithromycin and moxifloxacin resistance, in order to determine the resistance rates for these antimicrobials and their evolution throughout the study period.

A total of 142/3633 (3.9%) patients who tested positive for MG were included in the study. The first sample from the first episode was taken for each patient. The assay used to diagnose the MG infection was the RT-PCR Allplex™ STI Essential Assay (Seegene®, Seoul, South Korea). Specimens positive in this assay were subsequently tested by the RT-PCR Allplex™ MG & MoxiR Assay (Seegene®) and RT-PCR Allplex™ MG & AziR Assay (Seegene®) for azithromycin, as well as moxifloxacin resistance-associated mutations. The biological specimens were endocervical and urethral swabs that were transported in DeltaSwabs Amies (Deltalab S.L., Barcelona, Spain) and first-void urine samples in a sterile sample container.

MG was detected in 76 (53.5%) male and 66 (46.5%) female patients. Resistance-associated mutations against macrolides were detected in 39/142 (27.46%) strains and against fluoroquinolones in 14/142 (9.86%) strains. The median age was 29 (IQR 25–37.25; 17–58) years, and the prevalence was significantly higher in male patients (44.7% vs. 13.2%, p=0.049).

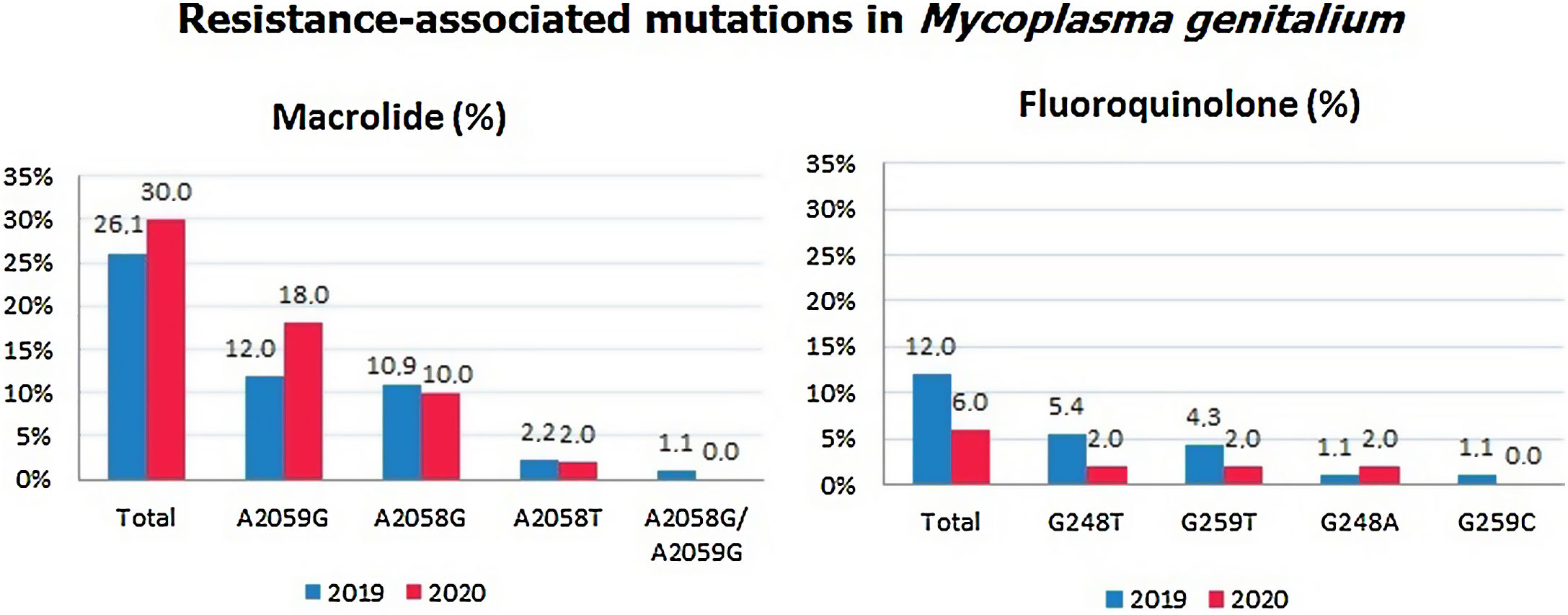

The percentage of SNPs detected in the 23S rRNA was 26.1% in 2019 and 30% in 2020, while the percentage of SNPs detected in the parC gene was 12% in 2019 and 6% in 2020. Detailed information about these detected mutations by year is shown in Fig. 1.

Throughout the study period, we found a slight increase of 3.9% in the resistance rate to azithromycin. The prevalence of mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance alone decreased from 12% in 2019 to 6% in 2020. Both evolutions between these 2 years, were not statistically significant.

The most frequent SNP detected was A2059G (37.7%), while A2058G (28.3%) was in second position.5 Dual mutations conferring resistance to both antimicrobials were found in a total of nine (17%) mutant strains: four A2059G/G248T, three A2058G/G259T and two A2059G/G248A. The presence of dual mutations could increase treatment failure, which was similarly concluded in a study where patients were followed up closely to observe the implication of the presence of dual markers after monotherapy.6

Treatment failure in MG infection is associated with recurrent or persistent NGU.7 Commercial PCR assays for the detection of these mutations allow for the resistance-guided treatment of MG infections, improving cure rates and preventing the spread of resistant strains. Furthermore, the fact that the study can be made with the same DNA extraction is an advantage over other commercial assays.

The main limitations of this study were the lack of a complete clinical history and the number of patients lost to follow-up, which would allow for an analysis of antibiotic failure. However, there is enough data available to support that the presence of these mutations causes treatment failure.3,7,8

Finally, the high macrolide resistance rates and the increase of resistance-associated mutations during the study period and, in addition, the established fluoroquinolone resistance rate, which was similar to that from other studies, supports the necessity of analyzing the presence of mutations to perform targeted treatment.