Acinetobacter baumannii is the most important genomic species of Acinetobacter from a clinical and epidemiological point of view. Nevertheless, genomic species other than A. baumannii are increasingly recognized as nosocomial pathogens. Molecular methods of identification (genotypic and proteomic assays) are more accurate and reliable and have greater discriminatory power than phenotypic methods.

Eleven genomic species of Acinetobacter spp. (8 A. baumannii, 1 A. pittii, 1 A. nosocomialis and 1 A. lwoffii) with different antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and mechanisms of resistance to antimicrobial agents were sent to 48 participating Spanish centers to evaluate their ability for correct identification at the genomic species level. Identification of the genomic species was performed at the two Clinical Microbiology reference laboratories (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Seville, Spain; and Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña, Spain) by partial DNA sequencing of the rpoB gene and MALDI-TOF. The mean percentage of agreement was 76.1%. Fifty percent of CC-01 (A. pittii) and 50% of CC-02 (A. nosocomialis) identification results were reported as A. baumannii. Discrepancies by type of systems used for identification were: MicroScan WA (51.1%), Vitek 2 (19.5%), MALDI-TOF (18.0%), Phoenix (4.5%), Wider (3.8%) and API 20 NE (3.0%). In conclusion, clinical microbiology laboratories must improve their ability to correctly identify the most prevalent non A. baumannii genomic species.

Acinetobacter baumannii es la genoespecie de Acinetobacter más importante desde el punto de vista clínico y epidemiológico. No obstante, otras genoespecies distintas de A. baumannii están adquiriendo cada vez mayor importancia como patógeno nosocomial. Los métodos moleculares (genotípicos y proteómicos) usados para la identificación de genoespecies de Acinetobacter son más precisos, fiables, y tienen mayor poder de discriminación que los métodos fenotípicos.

En este estudio se incluyen 11 genoespecies de Acinetobacter spp. (8 A. baumannii, 1 A. pittii, 1 A. nosocomialis y 1 A. lwoffii) con diferentes fenotipos de resistencia y mecanismos de resistencia antimicrobiana. Los aislados se enviaron a 48 centros españoles participantes para evaluar su capacidad para identificar correctamente la genoespecie de Acinetobacter. Las identificaciones de referencia se realizaron en 2 Laboratorios de Microbiología Clínica (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla, España; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña, España) mediante secuenciación parcial del gen rpoB y MALDI-TOF. El porcentaje medio de concordancia fue del 76,1%. El 50% de los resultados de identificación del control CC-01 (A. pittii) y el 50% de los resultados de identificación del control CC-02 (A. nosocomialis) se informaron como A. baumannii. Considerando el tipo de sistema de identificación usado las discrepancias fueron: MicroScan/WA (51,1%), Vitek 2 (19,5%), MALDI-TOF (18,0%), Phoenix (4,5%), Wider (3,8%) y API 20 NE (3,0%). En conclusión, los laboratorios españoles de microbiología clínica deben mejorar su capacidad para identificar correctamente las genoespecies de Acinetobacter distintas de A. baumannii que son más prevalentes.

The Acinetobacter genus includes more than 30 genomic species, of which A. baumannii (genomic species 2) is the most important from a clinical and epidemiological point of view.1 Nevertheless, other genomic species are increasingly recognized as nosocomial pathogens.2

Part of the success of this nosocomial pathogen, particularly A. baumannii, has been attributed to the ease with which it has adapted to the nosocomial environment and its facility for acquiring resistance to antimicrobials, including extended-spectrum antimicrobials like carbapenems, colistin and/or tigecycline.1–4

Correct identification of some genomic species of Acinetobacter spp. may be difficult because of the increasing number of genomic species recognized in the last years and the phenotypic similarity among some of these genomics species (i.e. A. calcoaceticus–A. baumannii complex). The problem of misidentification may have important consequences for the management of infections and outbreaks caused by these microorganisms because there are significant differences between them in terms of their pathogenicity, antimicrobial resistance and ability to cause outbreaks.

Phenotypic methods used for identification usually have insufficient discriminatory power, particularly for genomic species included in the A. calcoaceticus–A. baumannii complex.5–7 Molecular methods however are more accurate and reliable and have greater discriminatory power than phenotypic methods, as has been observed for some genotypic assays (i.e. ARDRA analysis and sequencing of the 16S-23S rDNA, rpoB and gyrB) and proteomic assays (MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry).7–15

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of clinical microbiology laboratories in Spain to correctly identify the most clinically relevant genomic species of Acinetobacter beyond assigning them to the A. calcoaceticus–baumannii complex.

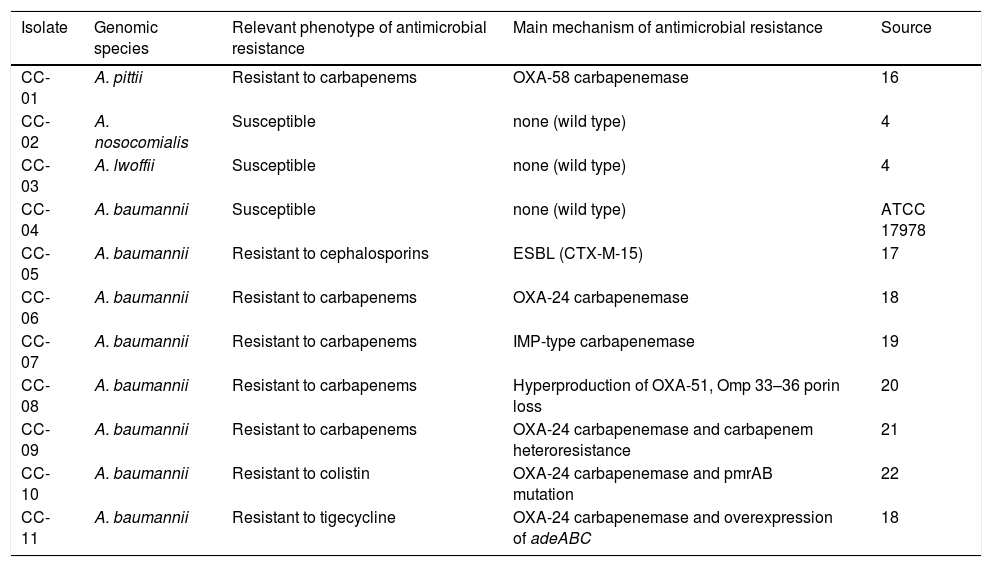

Materials and methodsEleven Acinetobacter spp. isolates, coded CC-01 to CC-11, were selected for this study. The panel included 9 clinical isolates (CC-01 to CC-03, CC-05 to CC-09 and CC-11) with different mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems, one laboratory-derived mutant resistant to colistin (CC-10) and the reference strain ATCC 17978 (CC-04) (Table 1)16-22. Isolates were sent in Amies transport medium to 48 participating hospitals in May 2014. The instructions specified that isolates should be treated as blood culture isolates.

Panel of Acinetobacter spp. reference isolates sent to participating laboratories.

| Isolate | Genomic species | Relevant phenotype of antimicrobial resistance | Main mechanism of antimicrobial resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC-01 | A. pittii | Resistant to carbapenems | OXA-58 carbapenemase | 16 |

| CC-02 | A. nosocomialis | Susceptible | none (wild type) | 4 |

| CC-03 | A. lwoffii | Susceptible | none (wild type) | 4 |

| CC-04 | A. baumannii | Susceptible | none (wild type) | ATCC 17978 |

| CC-05 | A. baumannii | Resistant to cephalosporins | ESBL (CTX-M-15) | 17 |

| CC-06 | A. baumannii | Resistant to carbapenems | OXA-24 carbapenemase | 18 |

| CC-07 | A. baumannii | Resistant to carbapenems | IMP-type carbapenemase | 19 |

| CC-08 | A. baumannii | Resistant to carbapenems | Hyperproduction of OXA-51, Omp 33–36 porin loss | 20 |

| CC-09 | A. baumannii | Resistant to carbapenems | OXA-24 carbapenemase and carbapenem heteroresistance | 21 |

| CC-10 | A. baumannii | Resistant to colistin | OXA-24 carbapenemase and pmrAB mutation | 22 |

| CC-11 | A. baumannii | Resistant to tigecycline | OXA-24 carbapenemase and overexpression of adeABC | 18 |

Identification of the isolates was verified independently at the two reference laboratories used in this study: the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Seville, Spain, and the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña, Spain. Identification to the genomic species level was performed by partial DNA sequencing of the rpoB gene and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.11,13 Participating laboratories were requested to the (i) genomic species identified and (ii) the laboratory method used for identification. Identification was considered as concordant when the result obtained in the participating center was identical to that obtained in the reference center. A result identified as belonging to the A. calcoaceticus–baumannii complex rather than being assigned to a specific genomic species was considered discordant.

ResultsFive hundred and eleven results were obtained using just one of the following semiautomated identification systems: MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany; 36%), MicroScan WalkAway (Dade Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA; 36%), Vitek 2 (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France; 15%), Wider I (Francisco Soria Melguizo, Madrid, Spain, 4%), Api 20NE (bioMérieux, 4%), Phoenix (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA, 3%) and DNA sequencing by the Sanger method (2%). Fourteen identification results were obtained using 2 or more of these semiautomated systems.

Overall mean concordance was 76.1%. Regarding the type of system used, discrepant results were obtained with the MicroScan WA (51.1%), Vitek 2 (19.5%), MALDI-TOF (18.0%), Phoenix (4.5%), Wider (3.8%) and API 20 NE (3.0%) systems. No discrepancies were observed for laboratories using DNA sequencing. Respect to type of isolate, overall concordance per isolate was 87.5% (CC-04, CC-05, CC-06 and CC-07), 85.4% (CC-11), 83.3% (CC-03, CC-09 and CC-10), 81.3% (CC-08), 37.5% (CC-01) and 33.3% (CC-02). Fifty percent of identification results for CC-01 (A. pittii) and 50% of results for CC-02 (A. nosocomialis) were reported as A. baumannii.

DiscussionThe genus Acinetobacter includes more than 30 genomic species, of which A. baumannii is the most important from a clinical and epidemiological point of view.1 Nonetheless, non-A. baumannii genomic species are increasingly being recognized as nosocomial pathogens, probably due to their ability to cause outbreaks and acquire resistance to multiple antimicrobials as A. baumannii.2

Genomic species identification of Acinetobacter can be carried out using phenotypic methods, but they have the drawback of limited reliability or discriminatory power, particularly for the genomic species belonging to the A. calcoaceticus–A. baumannii complex.5–7 The problem of misidentification may have important consequences for the management of infections and outbreaks caused by these microorganisms. In our study, the rate of erroneous identification was rather high, reaching almost 24% of all identification determinations performed, mostly of A. nosocomialis and A. pittii, which, together with A. baumannii and A. calcoaceticus, belong to the A.calcoaceticus–A. baumannii complex, as reported in previous studies.13 This may reflect the current inability of phenotypic systems to correctly identify the separate genomic species belonging to this complex.

Another source of error was the type of commercial system used, particularly the MicroScan WalkAway and Vitek 2 systems. This finding highlights the importance of using more than one phenotypic system for optimal identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. Real-time PCR may be useful for rapidly identifying some, but not all, Acinetobacter species. MALDI-TOF represents a promising method for the rapid and practicable identification of most Acinetobacter species and may, in a few years, prove to be an alternative to genotypic methods, including those based on DNA sequencing.15

An analysis of factors that contribute to discrepancies in the identification of Acinetobacter species should be a priority for clinical laboratories. One way to address this problem is to participate in quality control programs, which can be very helpful for detecting potential laboratory problems, as observed for antimicrobial susceptibility testing,23,24 and enabling corrective measures to be established for optimizing the process and the quality of the reports offered to clinicians.

In conclusion, this study clearly shows that microbiology laboratories need to improve their ability to correctly identify Acinetobacter genomic species.

FundingThis work was supported by the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (projects PI11-02046, PI10/00056 and PI12/00552) and the Consejería de Innovación Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía (P11-CTS-7730), Spain, by the Plan Nacional de I+D+i 2008-2011 and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/0015) – co-financed by European Development Regional Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ ERDF, and the Programa integral de prevención, control de las infecciones relacionadas con la asistencia sanitaria, y uso apropiado de los antimicrobianos (PIRASOA; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía).

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

We are grateful to the 48 participating centers and the SEIMC Quality Control Program for their indispensable help in making this study possible. The complete list of the 48 participating hospitals is as follows:

Hospital Universitario de Tarragona Joan XXIII (Tarragona, Tarragona; Angels Vilanova), Hospital General de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín (Las Palmas Gran Canaria, Las Palmas; Ana Bordes Benítez), Hospital Costa del Sol (Marbella, Málaga; Natalia Montiel Quezel-Guerraz), Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (Zaragoza, Zaragoza; Ana Isabel López Calleja), Hospital de Cabueñes (Gijón, Asturias; Luis Otero Guerra), Hospital Doce de Octubre (Madrid, Madrid; Fernando Chaves Sánchez), Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander, Cantabria; Jorge Calvo Montes), Hospital Sierrallana (Torrelavega, Cantabria; Inés de Benito población), Hospital Santa Barbara (Complejo Hospitalario de Soria, Soria; Angel Campos Bueno), Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (Valladolid, Valladolid; Raul Ortiz de Lejarazu Leonardo), Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega (Valladolid, Valladolid; Mónica de Frutos Serna), Complejo Asistencial de Avila (Avila, Avila; Antonio Gómez del Campo Dechado), Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real (Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real; Isabel Barbas Ferrera), Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara (Guadalajara, Guadalajara, González Praetorius), Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona; M Angeles Domínguez Luzón), Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid, Madrid; Ricardo Fernández Roblas), Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo (Vigo, Pontevedra; Maximiliano Alvarez Fernández), Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (A Coruña, A Coruña; Begoña Fernández Pérez), Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús (Madrid, Madrid; M Mercedes Alonso Sanz), Hospital de la Princesa (Madrid, Madrid; Laura Cardeñoso), Hospital General U. Gregorio Marañón (Madrid, Madrid; Carlos Sánchez), Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid, Madrid; Juan J Picazo de la Garza), Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Majadahonda, Madrid; Francisca Portero), Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Pamplona, Navarra; José Leiva León), Hospital Comarcal Marina Baixa (Villajoyosa, Valencia; Carmen Martínez Peinado), Hospital Universitario La Fe (Valencia, Valencia; José Luis López Hontangas), Hospital General Universitario de Elche (Elche, Alicante; Gloria Royo García), Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (Cádiz, Cádiz; Fátima Galán-Sánchez), Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria (Málaga, Málaga; Encarnación Clavijo Frutos), Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova (Lleida, Lleida; Mercedes García González), Hospital Lucus Augusti (Lugo, Lugo; Pilar Alonso García), Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra (Pontevedra, Pontevedra; María José Zamora López), Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid, Madrid; Julio García Rodríguez), Hospital Universitario Son Espases (Palma de Mallorca, Baleares; José L Pérez Sáenz), Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid, Madrid; María Isabel Morosini), Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria (Las Palmas de Gran Canarias, Las Palmas; Antonio Manuel Martín Sánchez), Hospital de Jerez (Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz; M Dolores López Prieto), Hospital de la Ribera (Alzira, Valencia, Javier Colomina Rodríguez), Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (Alcorcón, Madrid; Alberto Delgado-Iribarren), Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara (Cáceres, Cáceres; Jesús Viñuelas Bayón), Hospital Universitario Vall d́Hebron (Barcelona, Barcelona; Rosa Juve Saumell), Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla, Sevilla; Javier Aznar Martín), Hospital General Universitario de Albacete (Albacete, Albacete; Eva Riquelme Bravo), Hospital Universitario de Getafe (Getafe, Madrid; David Molina Arana), Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (Valencia, Valencia; Nuria Tormo), Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa (Leganés, Madrid; Pilar Reyes Pecharromán), Hospital Virgen de las Nieves (Granada, Granada; Consuelo Miranda Casas), Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (El Palmar, Murcia; Genoveva Yagüe).