The cascade of care of the hepatitis C are complex. The diagnosis of active infection in the same serum sample would simplify the process establishing a rapid access for patients to treatment. Our objective was to estimate the impact on healthcare and economic outcomes of the diagnosis of chronic infection in one-step diagnosis compared to standard diagnosis in Andalusia (8.39 million people).

MethodsA decision tree was developed to estimate the referral of patients with chronic infection, loss of follow-up, access to treatment and costs of the diagnosis of the infection, for both processes. The unit costs (€, 2018) of the health resources (medical visits, antibodies, viral load and genotype), without considering the pharmacological cost, were obtained from public sources in Andalusia.

ResultsOf the total estimated population (269,526 patients), 1389 patients would be referred to the specialised care in the one-step diagnosis and 1063 in de standard diagnosis, being treated 1320 and 1009, respectively. In one-step diagnosis, no negative viral loud patient would be referred to specialist versus 540 with standard diagnosis. One-step diagnosis would generate a cost saving of €184,928 versus standard diagnosis (€15,671,493 vs €15,856,421). When compared one-step diagnosis to standard diagnosis, the savings per patient with positive viral load referred to specialist would be €3634 (€11,279 vs €14,923).

ConclusionThe one-step diagnosis will achieve an increase in diagnosed patients, will increase the access of chronic patient to treatment and will generate cost savings, demonstrating its efficiency in the system in Andalusia.

Los circuitos de diagnóstico de la hepatitis C son complejos. El diagnóstico de infección activa en la misma muestra simplificaría el proceso estableciendo un acceso rápido al tratamiento. Nuestro objetivo fue estimar el impacto sanitario y económico del diagnóstico de la infección crónica en un solo paso (D1P) comparado con el diagnóstico tradicional (DTRA) en Andalucía (8,39 millones de personas).

MétodosSe realizó un árbol de decisión para estimar la derivación de los pacientes con infección crónica, pérdidas de seguimiento, acceso al tratamiento y costes del diagnóstico de la infección, para ambos procesos. Los costes unitarios, en euros (€) de 2018, de los recursos sanitarios (visitas médicas, anticuerpos, carga viral y genotipo), sin considerar el coste farmacológico, se obtuvieron de fuentes públicas de Andalucía.

ResultadosDel total de la población estimada (269.526 pacientes), 1.389 pacientes serían derivados al especialista en el D1P y 1.063 en el DTRA, siendo tratados 1.320 y 1.009, respectivamente. Con el D1P ningún paciente con carga viral negativa sería remitido al especialista, frente a los 540 con el DTRA. El D1P generaría un ahorro de costes de 184.928€ frente al DTRA (15.671.493 vs 15.856.421€). Al comparar el D1P frente a DTRA, el ahorro por paciente con carga viral positiva derivado al especialista sería de 3.644€ (11.279 vs 14.923€).

ConclusionesEl diagnóstico en un solo paso conseguirá un aumento de pacientes diagnosticados, aumentará el acceso de los pacientes crónicos al tratamiento y generará un ahorro de costes, demostrando su eficiencia en el sistema sanitario en Andalucía.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) has a high seroprevalence in the Spanish population, close to 1%,1–3 with rates of viraemia of 31–45%.1–3 Chronic disease is associated with a high morbidity and mortality4,5 and is the cause of a large number of hepatic disease-related deaths.6

Current direct-acting antivirals may manage to cure the disease in >95% of cases,7–9 reducing the risk of developing hepatic complications and mortality associated with the hepatitis C virus,10,11 but, for this, it is necessary to link the diagnosis to the treatment.

In Spain, the Plan Estratégico para el Abordaje de la Hepatitis C (PEAHC) [Strategic Plan for the Approach to Hepatitis C] was implemented in 2015 with the aim of reducing morbidity and mortality derived from chronic HCV infection by means of efficient prevention, diagnosis and treatment.9 Thanks to the actions performed since then, the number of infected patients in Spain has been reduced significantly.9,12 Despite this, there are still many people who are not aware of their infection status.2,13

Diagnosis of the infection consists of serology to detect antibodies against HCV (anti-HCV), which indicate previous contact with the virus, and the conduct of tests for the detection of virological markers, such as HCV-RNA or the HCV core antigen, which inform if there is active infection.7–9

Routine diagnostic tests are complex, and some anti-HCV+ detected patients are not referred to the specialist for assessment and subsequent treatment.14 For this reason, organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) have developed guidelines, which include the simplification of the diagnosis of hepatitis C.15 Likewise, scientific associations also recommend a rapid diagnosis.16 In this regard, the diagnosis of active infection in the same serum sample would simplify the process and would establish easy access to treatment for patients. Some studies have evaluated the implementation of a one-step diagnosis of chronic infection in Andalusia, showing that its establishment would increase significantly the referral of patients with active infection to specialist care. This would therefore increase the number of patients assessed for treatment.17 However, only 33% of Spanish centres perform it.18

From another perspective, the unnecessary repetitions of diagnostic tests which are carried out because of the referrals between specialists is an inefficiency of the system, resulting in a greater economic impact associated with the cost of the diagnosis and making access to treatment difficult for patients, with the possibility of losing a greater number of patients in each request for an analysis.

Increasing diagnostic rates is a key factor to advance in the elimination of HCV. Therefore, a rapid diagnosis for the identification of viraemic patients which facilitates and guarantees access to treatment is essential. Despite the fact that the one-step diagnosis is not implemented extensively in Andalusia, most laboratories consider that it is feasible, although with some technical and economic barriers to overcome.19 For this reason, the objective of the study was to estimate the health and economic impact of the one-step diagnosis (1SD) compared to the traditional diagnosis (TRAD) of chronic infection in Andalusia.

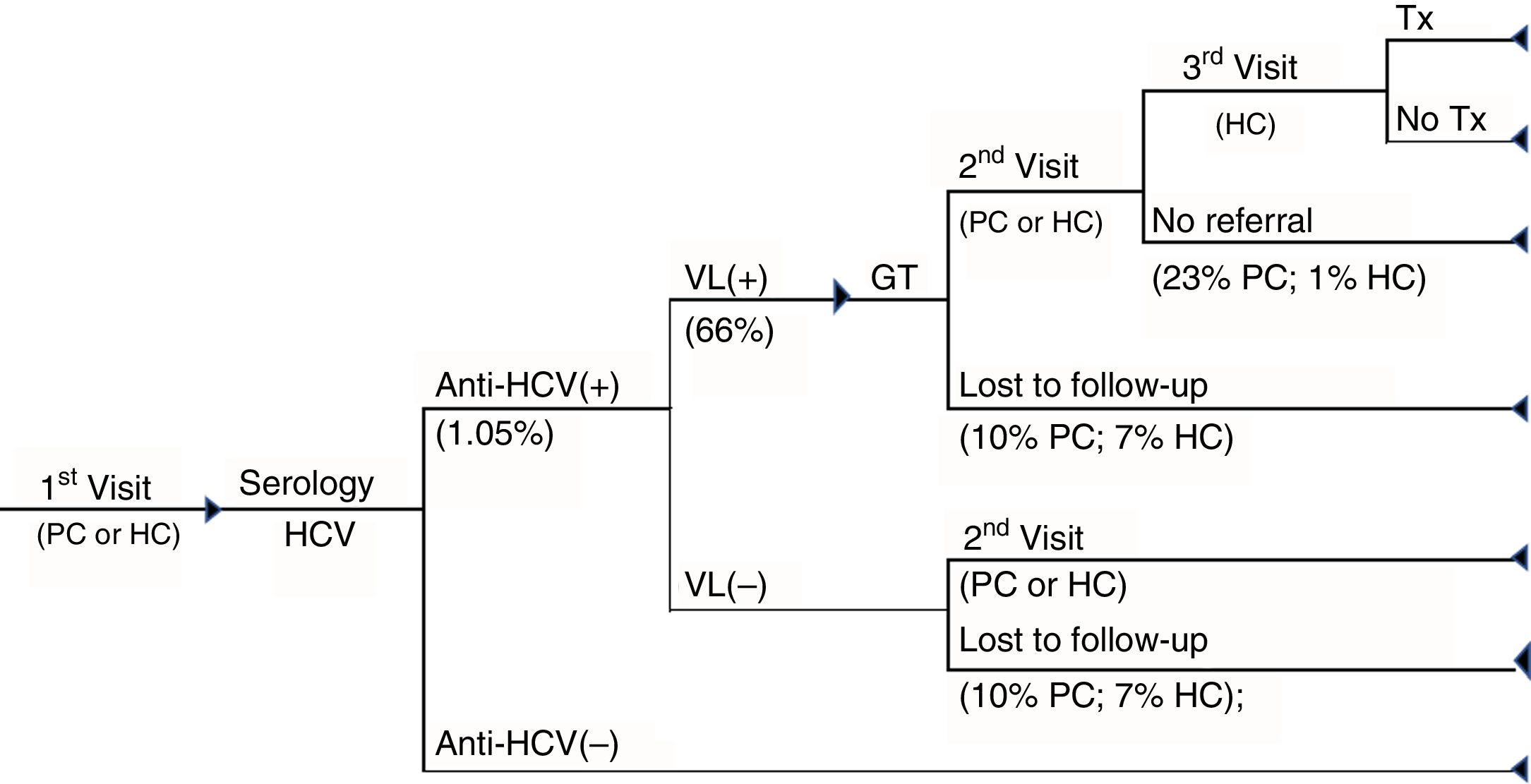

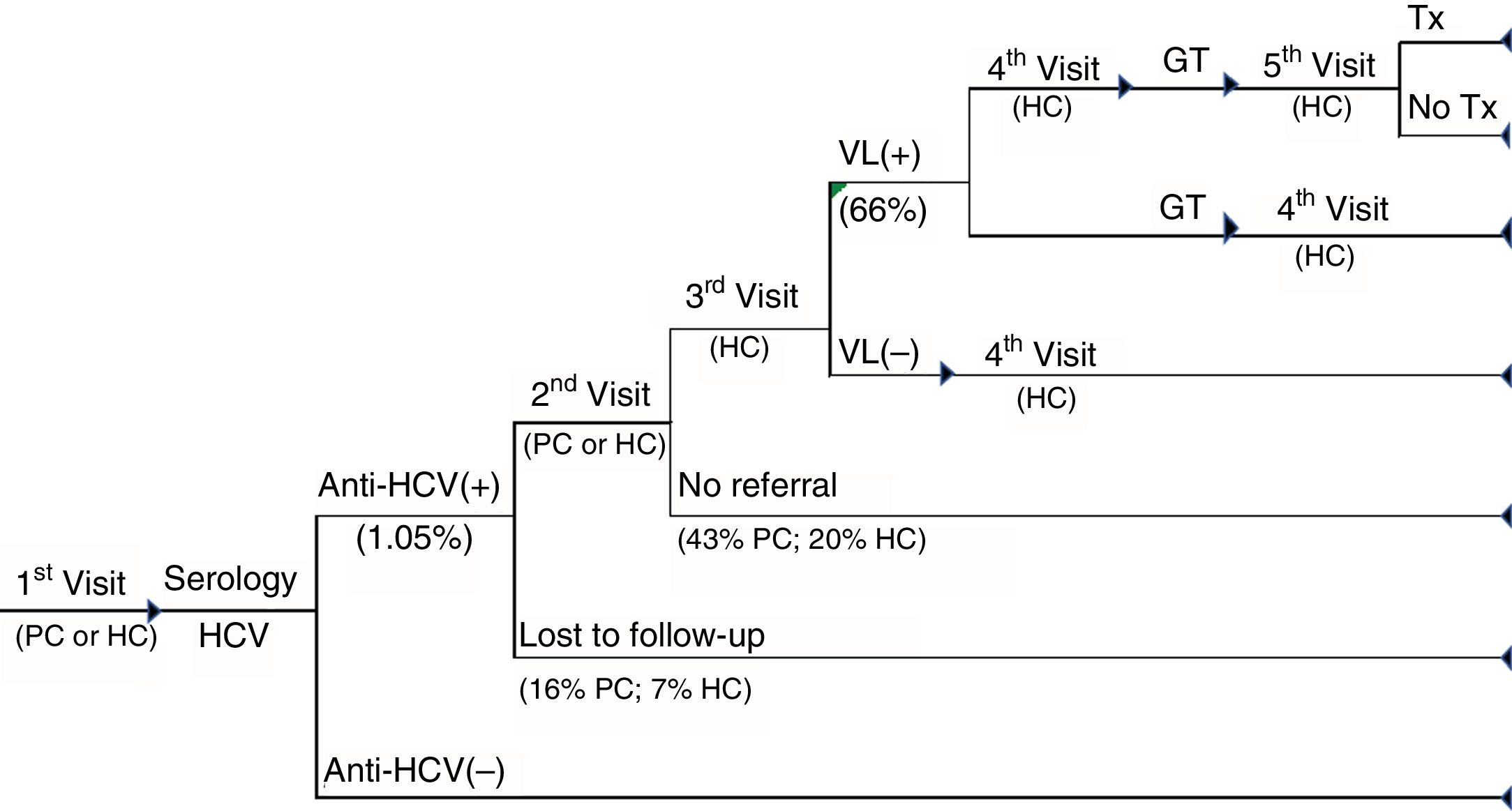

MethodsA decision tree (Excel 2010) was designed, comparing two diagnostic alternatives for HCV: 1SD and TRAD (Figs. 1 and 2).

1SD cascade of care. Cascade of care of patients with chronic hepatitis C of the one-step diagnosis from the first visit to primary care or hospital care to the diagnosis of the infection and whether or not patients have access to treatment. GT: genotype; HC: hospital care; PC: primary care; Tx: treatment; VL(+): positive viral load; VL(–): negative viral load.

TRAD cascade of care. Cascade of care for patients with standard-diagnosis chronic hepatitis C from the first visit to primary care or hospital care to the diagnosis of the infection and whether or not patients have access to treatment. GT: genotype; HC: hospital care; PC: primary care; Tx: treatment; VL(+): positive viral load; VL(–): negative viral load.

The analysis required the advice of a panel of experts made up of six clinicians from different health areas (microbiology and clinical parasitology, gastroenterology, hepatology and infectious diseases) with more than 25 years of experience to validate the values obtained in the literature and to estimate and agree on the use of resources associated with the cascade of care for the diagnosis of hepatitis C.

To construct the decision tree, from the opinion of experts the cascade of care was established for each diagnosis and the sequences of tests and medical visits were defined for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis C. The percentages of each decision tree branch were assigned based on the best scientific evidence published. In cases in which data were not available, these were established by the panel of experts.

It was estimated that, in one year, a total of 269,526 people in Andalusia would be subject to attending a primary care consultation or a routine hospital outpatient consultation (with a distribution of 67%/33%, respectively) and a serology would be conducted for the diagnosis of HCV.

The cascade of care for 1SD was based on the conduct, in a single blood sample, of serology for the detection of anti-HCV antibodies, confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with the objective of measuring the viral load (VL) and the genotype, if the test is positive. If the patient is viraemic, he/she is referred to the specialist for the assessment of their treatment (Fig. 1).

In the TRAD care cascade, in addition to the medical visits between tests in positive patients, the referral to the specialist care centre (in 31% of patients), repetition of the serology before the conduct of the VL (in 10%) and an additional visit to the specialist before performing the genotyping (in 15%) were included. Viraemic patients are referred to the specialist for the evaluation of their treatment (Fig. 2).

Finally, in both care cascades patient loss to follow-up was considered as not attending to collect the results and patients with anti-HCV+ not being referred to the specialist. Similarly, it was assumed that all patients with anti-HCV – did not attend the consultation for the collection of the results.

Healthcare resources associated with the diagnosis were: anti-HCV, VL, genotyping and medical visits (primary and specialist care). The analysis was conducted from the point of view of the Andalusian Health Service, meaning that only differential direct healthcare costs (euros [€] from 2018) were included. The costs of the necessary healthcare resources for the conduct of the model were obtained from the public prices of healthcare services from the Regional Government of Andalusia and hospital databases20,21 and are shown in Table 1. The laboratory personnel cost per test carried out was calculated based on a daily working day of a laboratory technician22 and the estimated time to analyse the diagnostic test. The cost of a medical consultation with the hospital specialist was estimated as the average of costs of the different specialists related to hepatitis C. The pharmacological cost of the antiviral therapies was not considered in the analysis. Due to the fact that the time frame considered is one year, no discount rate for the costs was considered.

Parameters and unit costs considered in the analysis.

| Parameters | Base case | Range of values (min.–max.) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||

| Target population | 269,526 | 529,678 | Panel of experts |

| Values (%) | Values (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First consultation | |||

| First consultation, PC | 67 | 55–74 | Panel of experts |

| First consultation, HC | 33 | 18–45 | Panel of experts |

| HCV(+) prevalence | 1.05 | 0.8–1.9 | 1–3 |

| Viral load (+) | 66 | 62–70 | 17 |

| Treatment | 95 | 90–100 | Panel of experts |

| Specific TRAD | |||

| Collection of results | |||

| Primary care | 84 | 72–95 | Panel of experts |

| Hospital care | 93 | 90–99 | Panel of experts |

| Patient not referred | |||

| Primary care | 43 | 28–50 | 17 |

| Hospital care | 20 | 15–25 | Panel of experts |

| Repetition of serology | 10 | 5–15 | Panel of experts |

| Extra visit before GT | 15 | 10–19 | Panel of experts |

| Specific 1SD | |||

| Collection of results | |||

| Primary care | 90 | 85–95 | Panel of experts |

| Hospital care | 93 | 90–99 | Panel of experts |

| Patient not referred to treatment | |||

| Primary care | 23 | 15–31 | Panel of experts |

| Hospital care | 10 | 5–15 | Panel of experts |

The results which made it possible to analyse the effectiveness of the detection and access to treatment were divided up according to the value that they brought to the Health System and to patients into (a) positive results: number of patients with VL+ referred to the specialist and with access to treatment; (b) negative results: number of patients with VL– referred to the specialist, lost to follow-up and not referred.

The economic outcomes were expressed as the total cost of the healthcare resources used during the diagnosis of the patient in the 1SD versus the total cost in the TRAD, as well as the average cost per patient with VL+ or VL– referred to the specialist.

Sensitivity analysisUncertainty was measured with univariate sensitivity analyses which evaluated the effect of each parameter individually on the results, based on the range of maximum and minimum values. In the parameters without information, a variation of ±20% was assumed based on the published literature or the information provided directly by the panel of experts. The range of maximum and minimum values for each parameter is shown in Table 1. In addition, an analysis was performed with a variation of ±10%, of ±20% and of ±30% on the unit cost of infection diagnostic tests.

ResultsOut of the total population considered as subject to attending a consultation and on which serology would be conducted for the diagnosis of HCV in Andalusia in one year, which was estimated at 269,526 people, 2830 would have anti-HCV+ and 1876 a VL+ (Table 2). Of these viraemic patients, 31% of additional patients with VL+ with 1SD (1389 patients) compared to TRAD (1063 patients) would be diagnosed and referred to the specialist for follow-up of the disease, which would result in a greater number of patients with access to treatment (1320 and 1009 with 1SD and TRAD, respectively) (Table 3).

Population results.

| 1SD/TRAD care cascade | |

|---|---|

| Total population | 269,526 |

| Anti-HCV prevalence | |

| Anti-HCV+ | 2830 |

| Anti-HCV− | 266,696 |

| Total | 269,526 |

| Viral load (anti-HCV+) | |

| VL+ | 1876 |

| VL− | 954 |

| Total | 2830 |

1SD: one-step diagnosis; HCV: hepatitis C virus; TRAD: traditional diagnosis; VL+: positive viral load; VL−: negative viral load.

Clinical outcomes.

| 1SD care cascade | TRAD care cascade | Difference | Difference, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive outcomes for the health system and patients | ||||

| Patients with VL+ referred to the specialist | 1389 | 1063 | 327 | 30.8% |

| Access to treatment (95%) | 1320 | 1009 | 311 | 30.8% |

| Negative outcomes for the health system and patients | ||||

| Patients with VL− referred | 0 | 540 | –540 | –100.0% |

| Lost to follow-up | 255 | 369 | –114 | –30.9% |

| Patients not referreda | 318 | 859 | –541 | –63.0% |

In addition, of the 2830 patients with anti-HCV+, with the 1SD no patient with VL– would be referred unnecessarily to the specialist, compared to 540 with the TRAD. Compared to the 1SD, with the TRAD 63% more patients with positive serology would not be referred to the specialist for assessment (859 and 318 with TRAD and 1SD, respectively) and in 114 additional patients a loss to follow-up would occur (Table 3).

The economic outcomes showed that the 1SD would involve a total cost of €15,671,493, compared to €15,856,421 with the TRAD, achieving a cost saving of €184,928 for the entire population assessed (Table 4). The cost of the medical visits accounted for the greatest share of the total cost. When comparing the 1SD against the TRAD, the saving per patient with positive VL referred to the specialist was €3644 (€11,279 vs €14,923) (Table 4).

Economic outcomes.

| 1SD care cascade | TRAD care cascade | Difference | Difference, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total costs | €15,671,493 | €15,856,421 | €−184,928 | −1.17% |

| Medical visits | €14,995,124 | €15,252,927 | €−257,803 | −1.69% |

| Diagnostic tests | €676,369 | €603,495 | €72,875 | 12.08% |

| Primary care | ||||

| Medical visits | €3,400,318 | €3,537,398 | €−137,080 | |

| Diagnostic tests | €453,168 | €394,417 | €58,751 | |

| Total | €3,853,485 | €3,931,814 | €−78,329 | |

| Hospital care | ||||

| Medical visits | €11,594,806 | €11,715,529 | €−120,723 | |

| Diagnostic tests | €223,202 | €209,078 | €14,124 | |

| Total | €11,818,008 | €11,924,607 | €−106,599 | |

| Relationship between clinical and economic outcomes | ||||

| Average cost per | ||||

| Patient with VL+ referred | €11,279 | €14,923 | €−3,644 | |

| Patient with VL− referred | €0 | €29,358 | €−29,358 | |

1SD: one-step diagnosis; TRAD: traditional diagnosis; VL+: positive viral load; VL−: negative viral load.

The sensitivity analyses show the robustness of the analysis of the base case, meaning that any variation in the minimum and maximum values of the parameters included in the analysis increases or decreases the difference in the number of patients with anti-HCV+ and with VL+ detected, but maintains the fact that the 1SD produces better clinical outcomes than the TRAD.

Furthermore, in all the univariate sensitivity analyses performed, compared to the TRAD, the 1SD generated savings for the health system, with the total cost for the entire population varying between –€103,222 and –€363,424. The parameters with the greatest influence on the economic outcomes were the population and the cost of the medical visit to hospital care.

Table 5 shows the results of the sensitivity analyses with the parameters associated with population and the cascade of care with the greatest influence on the final results.

Sensitivity analysis results.

| Base case values | Values, min. and max. | Patients with anti-HCV+ | Patients with VL+ | Patients with VL+ referred | Patients lost to follow-up | Patients not referred | Patients with VL(−) referred | Total cost entire population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case results | 2830 | 1876 | 327 | 114 | 541 | 540 | €−184,928 | ||

| Parameter | |||||||||

| Population | 269,526 | 215,621 | 2264 | 1501 | 261 | 91 | 433 | 432 | €−147,942 |

| 529,678 | 5562 | 3687 | 642 | 224 | 1063 | 1061 | €−363,424 | ||

| First consultation in PC | 0.67 | 0.55 | 2830 | 1876 | 300 | 93 | 507 | 570 | €−209,662 |

| 0.74 | 2830 | 1876 | 343 | 126 | 561 | 522 | €−170,500 | ||

| HCV+ prevalence | 0.0105 | 0.0084 | 2264 | 1501 | 261 | 91 | 433 | 432 | €−147,942 |

| 0.019 | 5121 | 3395 | 591 | 206 | 979 | 977 | €−334,632 | ||

| Viral load (+) | 0.66 | 0.63 | 2830 | 1772 | 309 | 114 | 559 | 599 | €−195,075 |

| 0.70 | 2830 | 1981 | 345 | 114 | 523 | 481 | €−174,781 | ||

| Collection of results in PC (TRAD, 1SD) | (0.84; 0.90) | (0.72; 0.85) | – | – | 363 | 242 | 459 | 497 | €−146,022 |

| 0.95 | – | – | 296 | 0 | 616 | 580 | €−220,742 | ||

| Collection of results in HC (TRAD, 1SD) | 0.93 | 0.90 | – | – | 325 | 114 | 537 | 533 | €−179,693 |

| 0.99 | – | – | 331 | 114 | 548 | 555 | €−195,398 | ||

| Non-referral in PC (TRAD, 1SD) | (0.43; 0.23) | (0.28; 0.05) | – | – | 78 | 114 | 211 | 621 | €−276,877 |

| (0.31; 0.50) | – | – | 491 | 114 | 743 | 503 | €−135,822 | ||

| Non-referral in HC (TRAD, 1SD) | (0.20; 0.10) | (0.15; 0.05) | – | – | 327 | 114 | 555 | 525 | €−174,324 |

| (0.25; 0.15) | – | – | 327 | 114 | 526 | 555 | €−195,533 | ||

1SD: one-step diagnosis; HC: hospital care; PC: primary care; TRAD: traditional diagnosis; VL+: positive viral load; VL−: negative viral load.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents a high burden of the hepatic disease worldwide. The international objective established by the WHO is the elimination of hepatitis by 2030.23 In Spain, this objective is expected to be achieved by 2021.24 In order to achieve it, it is necessary to advance in various ways and to consolidate various pillars. The first of these would be to promote screening and early diagnosis. Since the implementation of the PEAHC, numerous patients have been treated, most of them in advanced stages of the disease,9 generating a patient profile with a more mild, asymptomatic and difficult-to-detect disease. A general screening in the adult population would help to increase the diagnosis of cases of occult active infection, who are unaware that they are suffering from the disease.25 Furthermore, there are studies, in Spain and in other countries, which show that screening is cost-effective.13,25–27

The second pillar which would promote achieving the elimination of the disease would be developing measures aimed at improving the process related to the diagnosis of patients with HCV. In Spain, the cascades of care for diagnosis are excessively complicated. The total duration from the first visit to the primary care doctor or the specialist until the patient receives the diagnosis can take up to one year.28,29 In addition, during this time numerous medical visits are carried out and unnecessary tests are repeated which cause losses of patients with positive diagnosis of infection and increase the costs. The implementation of the 1SD would help to improve continuity of care, reducing times for the diagnosis and preventing the loss to follow-up of viraemic patients, thereby reinforcing the health and economic outcomes of screening for hepatitis C.

In this regard, the results of our analysis strengthen the importance of implementing strategies to improve the diagnostic process of HCV infection. Our study shows that, for the estimated population subject to undergoing serology for HCV in Andalusia, the 1SD versus the TRAD would save costs, while also achieving better health outcomes. The 1SD provides greater effectiveness, taking into account the number of patients detected, diagnosed and with access to treatment. Furthermore, the 1SD has a lower cost associated with the reduction of diagnostic tests and medical visits. It is therefore a cost-effective strategy.

Studies conducted in other countries have evaluated the efficiency of conducting rapid diagnostic tests compared to routine or standard diagnostic tests. However, due to differences in the definition of rapid diagnosis or in the test used for its conduct, in the study populations or in the methodology, this study cannot be compared with them. Nevertheless, its conclusions are similar, concluding that the use of rapid diagnoses to detect HCV infection is cost-effective, increasing the number of individuals with infection who are detected.30

Moreover, the strengthening of the inter-level collaboration and between different healthcare professionals is essential in any strategy to implement an effective and efficient measure. There are sufficient resources available to carry out the 1SD in most Spanish hospitals (81%).18 However, it is only carried out in 31% of them.18 The collaboration of all agents involved in the process is necessary to continue advancing towards elimination.

In addition, another point that would bring additional value to the 1SD would be to establish alert strategies in primary and specialist care in the event of a positive result with active infection, making the diagnosis of infection even more effective.31–33

The limitations of the study which should be mentioned include the lack of clinical and economic information in the published literature for the modelling of cascades of care and carrying out analysis. Currently, there are no data published on the distribution of patients in the cascades of care. Nor is there information available in the literature on the cost of some of the tests and medical visits, which made the participation of a panel of experts necessary. In order to collect the variability effect of the main parameters on the results, sensitivity analyses were performed. In the different scenarios of prevalence (anti-HCV and VL), population or cost variation, the study result remained cost-effective.

Lastly, the final pillar to achieve elimination of HCV would be to facilitate access to treatment for viraemic patients. In this context, current direct-acting antivirals with an effectiveness of greater than 95% in terms of sustained virologic response,7–9 in addition to reducing hepatic morbidity and mortality related to HCV, improve survival, patients’ quality of life and have proven to be cost-effective.10,11 This study's model has not taken into account the health outcomes that would be achieved with access to direct-acting antiviral treatment, measures such as life years gained or quality-adjusted life years and the total costs in the long term.

ConclusionBased on the results presented in the study, it can be concluded that the 1SD of patients with chronic hepatitis C is an efficient strategy compared to the TRAD in Andalusian centres, which provides additional value to the health system and to patients, due to the reduced number of medical visits and unnecessary diagnostic tests and to the reduced costs associated with these processes.

FundingFunding not conditional on the results was received from Gilead Sciences for the conduct of the project.

Conflicts of interestFederico García received allowances for attending conferences and scientific meetings, financial compensation for talks and grants for carrying out research projects and biomedical education activities from Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, ViiV Healthcare, AbbVie, Abbott, Roche, Qiagen, Werfen and Hologic. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Juan Carlos Alados received allowances for attending conferences and scientific meetings, financial compensation for conferences and biomedical education activities from Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Abbott Diagnostics and Roche Diagnostics. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Juan Macías provided consultancy services, received payments for conferences, including the panel of experts service, and has been an investigator in clinical trials by Bristol Myers-Squibb, Gilead and Merck Sharp & Dohme. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Juan Manuel Pascasio attended the panel of experts and conferences for Gilead and AbbVie. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Francisco Téllez attended courses, conferences and scientific meetings for AbbVie, Gilead and MSD. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Marta Casado was an adviser and speaker for Gilead Sciences, AbbVie and MSD. There are no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Raquel Domínguez-Hernández and Miguel Ángel Casado are employees of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), a consultancy firm specialising in the Economic Evaluation of Health Interventions which received funding not conditional on the results from Gilead Sciences for the conduct of the project.

Please cite this article as: García F, Domínguez-Hernández R, Casado M, Macías J, Téllez F, Pascasio JM, et al. La simplificación del proceso de diagnóstico de la hepatitis C crónica es una estrategia coste-efectiva. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2019.03.001