The research identified the influence of assertiveness training against teenage depression in high scholars in Kepahiang Regency, Bengkulu, Indonesia.

MethodThis study used a quasi-experiment approach with pre-test and post-test design and a control group. Eighty students were engaged through simple random sampling.

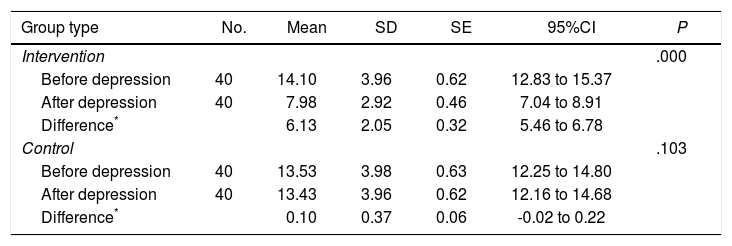

ResultsThe study found the frequency of depression in teenagers and considered the effect of assertiveness training. 14.10 teens were counted as depressed before assertiveness training provision, while the post-training average was 7.98 (p = .000). Assertiveness training had a significant effect on the prevalence of depression in the intervention group.

ConclusionsThe study recommends schools to cooperate with health services to increase mental health programs such as building peer groups, delivering assertiveness training, and teaching stress management to prevent depression in teenagers.

Adolescence is a transitional condition from childhood to adulthood in which growth is needed. If teens do not grow as needed, they can feel disappointed, lose respect for themselves, and assume themselves cowardly. These feelings can lead to depression1. Depression is defined as a disruption of psychology in which a great deal of negative feeling occurs within two weeks2. The symptoms of depression based on the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) are fatigue, loss of concentration, decreased interest and excitement, reduction of self-esteem and self-confidence, reduction of mood through the day, ideas of suicide, suicide attempts, or plans for suicide3.

The Anxiety and Depression Association of America in Sa-dock et al4 said that 18% of the population of 40 million people felt depression below the age of 13, and 5.6% between age 13-185. Prevalence of depression in Indonesia's population of 14 million was 6% for ages 15 and over, with 2.7% of them in Bengkulu province alone6.

Efforts have been made by the government to combat depression in teens through the programs of Usaha Kesehat-an Sekolah (UKS) and Pusat Informasi dan Konsultasi Remaja (PIKR) at school, but those programs are not optimized. They focus on behavioral counseling for the teens. There is no mention of interventions for depression. Puskesmas has a program called Program Kesehatan Peduli Remaja (PKPR), but it only treats drug abuse (NAPZA). Because of this focus, a nurse is required to help teens in the program with the problems caused by depression.

Stuart's stress adaptation model shows that nursing care for teens with depression should focus on improving self-esteem and encouraging the expression of emotions7. Teens should also participate in assertiveness training (AT), a therapy that promotes the ability to show negative feelings productively. AT is a nursing modality in the form of group behavioral therapy. Teens learn how to express their feelings, thoughts, and desires directly, honestly, and freely but with respect for others8. They learn to regard themselves positively as their assertiveness is successfully built9.

AT can be beneficial for everyone. It gives an opportunity for people to share their experiences, help others, and solve problems. This activity helps those who struggle to say no or express affection or negative feelings10.

Research conducted by Eslami et al9 on 63 students with depression shows that AT succeeded to reduce depression in teens by 36.5%. Another study states that increased assertive behavior can reduce depression in nursing students11. AT gives teens the skills to solve problems and determine priorities. Using support systems within the community can ensure that no depression follows the training12.

The results of previous studies have proven the success of AT, but there has been no research on AT and its influence on teens in Indonesia, especially in Bengkulu. There is minimal data about AT treatment and its influence in general. Thus, the number of teen suicides in Indonesia, especially in Bengkulu, is quite high.

Based on Bengkulu province police reports, the incidence of teen suicide in 2014 and 2015 were 26 and 24 people, or 1.30% and 1.44% respectively. The highest incidence rates occurred in the Kepahiang Regency. In January through April 2016, there were five cases of teen suicide in Bengkulu province, and two of them occurred in the Kepahiang Regency. A report of medical records from Dr. M. Yunus Hospital in Bengkulu determined the majority of suicides in 2014 and 2015 were caused by drinking pesticide. Of these, 38.4% and 53.8% were carried out by people ages 15 to 24. The incidence numbers have increased every year.

A preliminary study was held on April 23rd and 25th at High School of Government 01 Kepahiang with 536 grade 10 and 11students. Ten students were interviewed. Five of them often missed school and felt bored, fatigued, and lacking in concentration. Another three students felt sad, depressed, and lost interest or pleasure in doing things. The final two students had negative self-images, saw the future without hope, and had decreased interest or pleasure in doing anything.

An interview with the counseling teacher revealed that one student hanged himself with no apparent cause in 2014. One student drank pesticide and died in January 2016. Another student in March 2016 committed suicide by hanging himself. The data indicate that further study should be conducted on the effect of AT on teen depression at High School of Government Kepahiang Regency in Bengkulu.

MethodsThe research was a quantitative study using quasi-experimental design. It used a pre-test and post-test approach with a control group. This quasi-experimental intervention study aimed to evaluate the effect of AT program on student's depression at High School of Government Kepahiang, Bengkulu. There were 80 teens sampled, and randomly divided into intervention and control groups (40 teens for each group). The experimental group received the AT for 1 month. The main objective of this program was to enable students to improve their assertiveness skills thus decreasing levels of depression.

The AT was conducted in 6 sessions as follows: 1) training to understand the different characteristics of assertive, aggressive, passive communication in others or peers; 2) training the ability to become an active listener of friends or others to express desires and needs; 3) training to express teenage differences in joint decision; 4) training to convey expectations to change negative behavior to friends or others; 5) training to say “no” to irrational requests, and 6) training to maintain assertive behavior in various situations. Each session was delivered approximately for 60 min.

A module was developed by the researchers and experts as a reference during the AT provision. In addition to the module, the researchers also prepared a workbook for teenagers containing the AT materials ranging from first to sixth sessions with language that was easily understood by the respondents. The workbooks were useful to monitor the implementation of the teenager's assertive behavior at each session.

Ethics approval was obtained from vice-chancellery for research in Andalas University of Medical Sciences. The students in the intervention group were intimated with details of the study, asked to read and sign a consent form, and assured of the confidentiality. Participation to study was voluntary; students were given the opportunity to leave the study if they become uncomfortable. The control group was given the opportunity to participate in the assertiveness program after the study was completed.

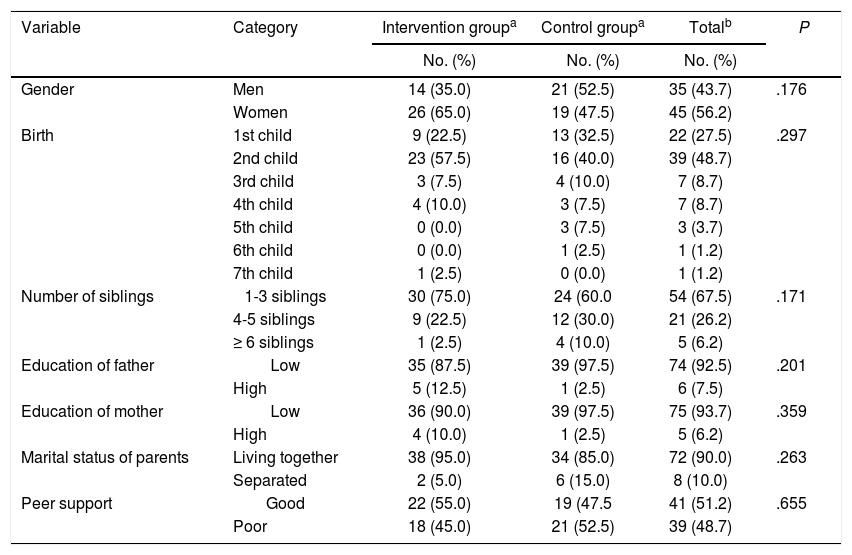

ResultsTeen characteristics and depression peer supportTable 1 shows that most students with depression are women (56.3%), and second children (48.8%) have 1-3 siblings (67.5%), a father with low education (97.5%), and a mother with low education (93.8%). Most had parents living together (90%) and good peer support (51.3%). Statistical results obtained P-value >.05 which mean that both groups are homogeneous (aP >.05). Table 2 show the differences between intervention and control group before and after getting AT for teen depression in teenage high school students in Bengkulu, Indonesia.

Characteristics of frequency distribution and peer support for depression in teenage high school students in Bengkulu, Indonesia

| Variable | Category | Intervention groupa | Control groupa | Totalb | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Gender | Men | 14 (35.0) | 21 (52.5) | 35 (43.7) | .176 |

| Women | 26 (65.0) | 19 (47.5) | 45 (56.2) | ||

| Birth | 1st child | 9 (22.5) | 13 (32.5) | 22 (27.5) | .297 |

| 2nd child | 23 (57.5) | 16 (40.0) | 39 (48.7) | ||

| 3rd child | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.0) | 7 (8.7) | ||

| 4th child | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (8.7) | ||

| 5th child | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (3.7) | ||

| 6th child | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| 7th child | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Number of siblings | 1-3 siblings | 30 (75.0) | 24 (60.0 | 54 (67.5) | .171 |

| 4-5 siblings | 9 (22.5) | 12 (30.0) | 21 (26.2) | ||

| ≥ 6 siblings | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10.0) | 5 (6.2) | ||

| Education of father | Low | 35 (87.5) | 39 (97.5) | 74 (92.5) | .201 |

| High | 5 (12.5) | 1 (2.5) | 6 (7.5) | ||

| Education of mother | Low | 36 (90.0) | 39 (97.5) | 75 (93.7) | .359 |

| High | 4 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | 5 (6.2) | ||

| Marital status of parents | Living together | 38 (95.0) | 34 (85.0) | 72 (90.0) | .263 |

| Separated | 2 (5.0) | 6 (15.0) | 8 (10.0) | ||

| Peer support | Good | 22 (55.0) | 19 (47.5 | 41 (51.2) | .655 |

| Poor | 18 (45.0) | 21 (52.5) | 39 (48.7) |

Analysis of before and after assertiveness training for depression in teenage high school students in Bengkulu, Indonesia (n = 80)

| Group type | No. | Mean | SD | SE | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | .000 | |||||

| Before depression | 40 | 14.10 | 3.96 | 0.62 | 12.83 to 15.37 | |

| After depression | 40 | 7.98 | 2.92 | 0.46 | 7.04 to 8.91 | |

| Difference* | 6.13 | 2.05 | 0.32 | 5.46 to 6.78 | ||

| Control | .103 | |||||

| Before depression | 40 | 13.53 | 3.98 | 0.63 | 12.25 to 14.80 | |

| After depression | 40 | 13.43 | 3.96 | 0.62 | 12.16 to 14.68 | |

| Difference* | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.06 | -0.02 to 0.22 |

Results of the analysis showed that depression experienced by teens at High School Government Kepahiang Regency (Bengkulu) is a moderate depression. The intervention group shows the reduction of depression after AT (P = .000). Thus, depression in teens can be reduced or changed from moderate to mild through AT.

Teens who participated in the research had moderate depression, but after AT, their depression was reduced9,13-15. The training lasted until the teenage participants changed their behavior and attitudes. Therapy was held in a group so teens could share their experiences, help each other, and solve problems. AT aims to address the cognitive aspects of depression, but also attitudes and behavior. The group developed during the therapy process by following models and demonstrations of assertive skills. Demos were effective since they related to real issues faced by group members. The therapy group emphasized the learning process through various situations, developing assertive abilities step by step.

In general, AT can help teens reduce depression. It asks them to be open in expressing their problems. Progressively, the teens' assertive ability is evaluated and they are given tasks to implement in everyday life within family, school, and community. This fits the findings of previous studies showing positive results of assertiveness therapy on depression in different places, such as that conducted by Eslami et al9 in Tehran, Tavakoli et al16 in Iran, and Rezayat and Deh-ghan Nayeri11 in Tehran.

The control group results were different from those of the intervention group. The study indicates the reduction of depression before and after the treatments but not by a significant margin (P = .10). The control group's depression remained in the range of moderate depression even after the study. This aligns with the results of research conducted by Larkin and Zayfert17 in Mohebi et al15 which shows value reduction after giving an intervention to the control group. Another study conducted by Eyberg et al18 on the therapeutic effectiveness of AT to moderate depression in the control group does not show significant levels of depression after AT is given.

The slight changes in depression in the control group happened because of social and personal factors, namely by having parents who live together and can nurture, educate, and develop their children. In addition, they are supported by a good peer group. This can be important, as 65% of teens in this study report being dependent on assistance, advice, and sympathy from friends. They also report relying on encouragement (52.5%) and attention (75%) when they feel sad or disappointed.