To understand what the absence of the family during emergency care means to adult patients and their families to.

MethodA grounded theory study was conducted in two emergency units of two public hospitals in southern Brazil. From October 2016 to February 2017, 15 interviews with patients and 15 with family members were carried out. The data were analysed following the comparative method.

ResultsThe patients and families experienced the absence of the family in emergency care as a process of suffering caused by the separation of patient and family; they did not understand the reasons for family exclusion, and were resigned to the situation.

ConclusionUrgent care per se entails suffering in patients and their relatives; this suffering intensifies when the family is separated and cannot accompany the patient during emergency care. These results show the need to develop health strategies and policies that contribute to the comprehensive care of patients and families in hospital emergency units.

Conocer el significado que atribuyen pacientes adultos y sus familias a la ausencia familiar durante la atención de urgencia.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo siguiendo la propuesta de la teoría fundamentada con recogida de datos en 2 unidades públicas de urgencias hospitalarias, localizadas en el sur de Brasil. Se llevaron a cabo 15 entrevistas con pacientes y 15 entrevistas con familiares durante los meses de octubre de 2016 a febrero de 2017. Los datos fueron analizados siguiendo el método comparativo contante.

ResultadosLos pacientes y familiares vivencian la ausencia familiar en la atención de urgencia como un proceso de sufrimiento causado por la separación del binomio familia-paciente; por la falta de entendimiento acerca de los motivos que justifican la exclusión familiar, y por enfrentarse a la situación con resignación.

ConclusiónLa urgencia per se conlleva un sufrimiento en el paciente y sus familiares; este sufrimiento se intensifica cuando la familia es apartada y no puede acompañar al paciente durante la atención de urgencia. En vista de estos resultados, es necesario desarrollar estrategias y políticas sanitarias que contribuyan a la atención integral de pacientes y familias en unidades de urgencias hospitalarias.

Despite the backing of scientific bodies and the growing evidence supporting the presence of the family during emergency care, the attitudes and opinions of health professionals continue to have a negative influence on promoting this practice. Patients want to be with their loved ones during emergency care, while the chief concern of family members in the emergency waiting room is the possibility of the patient dying alone without being able to say goodbye or their needing emotional/spiritual support during their stay in the emergency department.

What does this paper contribute?Adult patients and family members perceive and describe the absence of the family during emergency care as a distressing experience caused by separation from the family. This is due to a lack of understanding of the reasons for excluding family members and their being resigned to the situation.

Implications of the studyThe findings of this study demonstrate the need to promote patient- and family-centred care in hospital emergency departments. This requires the development of strategies, infrastructure and health policies to promote the presence of family members in emergency departments.

Traditionally, medical and nursing teams are accustomed to considering family members as visitors to health services, rather than as people concerned about their sick loved ones and willing to participate in the processes of illness, treatment, recovery and even death.1 In fact, some authors conclude that critical and intensive care professionals generally do not translate family-centred care (FCC), which includes the implementation of values such as dignity and respect, information sharing, and family participation and collaboration, into clinical practice.2

Therefore, commonly, during emergency care – involving invasive procedures and/or cardiopulmonary resuscitation efforts – family members are not allowed to stay in the emergency department (ED).3 In recent decades, however, allowing relatives to accompany the patient in emergency care has been supported by professional bodies and scientific critical care societies1,4,5 and this in turn has been gaining the attention of researchers in this area.6–9 There have also been initiatives to humanise health care – such as the HU-CI project (Humanising Intensive Care) in the Spanish context – which aim to show that a change in procedures towards a humanistic, people and family-centred model results in care excellence.10,11

Since the end of the 1980s, when the first report on the presence of the family in emergency care was published,12 the subject has been studied from different approaches and perspectives. Research findings highlight the benefits of the presence of family members, such as promoting greater peace-of-mind and satisfaction in confirming that “everything possible” was done for the patient3,13–15; helping families understand the severity of life-threatening events6,7,16; fostering emotional support for patients and families8,17; guiding relatives in making the best decisions for the care and treatment of the patient18,19; and facilitating the grieving process for family members.15,20 All this relates to FCC, since it is based on the premise that the family is a fundamental element in the care of its members and that social isolation is a risk factor for family suffering, especially in critical situations. It is therefore recommended that professionals promote support networks and the closeness of the relationships that exist between most patients and their families.2

However, despite the backing of scientific bodies and the growing evidence supporting the abovementioned practice, the attitudes and opinions of health professionals continue to negatively affect promotion of the presence of the family in emergency care. Thus, most emergency departments in the world do not allow family members to be present. This is mainly because doctors and nurses understand that before any change in clinical practice there must be greater knowledge of the pros and cons of the presence of the family in the emergency department.21–23

We should note that information is increasingly available on the opinions of professionals as well as patients and families themselves. Several studies have identified the beliefs, attitudes and preferences of health professionals in relation to family presence and its effects on patients, relatives and the dynamics of the department.13,14,20 Research has also been conducted on the desire of patients to be with their loved ones during emergency care, because they believe in its benefits.7,9 Likewise, research on the experiences of family members shows that when left in the waiting room, they are concerned about the possibility of the patient dying alone without being able to say goodbye.22 However, there is no evidence to describe the social, dynamic and complex process that adult patients and family members experience together in the absence of the family during emergency care. Therefore, this research study seeks to answer the following question: What meaning do adult patients and their families attribute to the absence of the family during emergency care?

MethodA qualitative study was carried out from the perspective of grounded theory.24 The research setting was the ED of 2 health centres located in 2 different cities of Paraná, in southern Brazil.

Both departments are managed by the public health system, care for severely-ill patients on a continuous basis and had no institutional policies or systematised routines during data collection that allowed the presence of the family during emergency care, although family visits are usually allowed twice a day for 30min. We chose to conduct the research in these 2 departments because there are differences in terms of the geographic and social location of the population using them, as well as differences in physical structure, professional profile and clinical pictures attended. For example, one of the units is linked to a university hospital that is the referral hospital for 30 municipalities, has a doctor, a resident doctor, a nurse and 2 nursing technicians and attends approximately 7 patients/day, mainly young people, victims of trauma and violence, and in a very serious condition. The mean patient stay in the emergency unit is 3 days. However, the second ED selected for this study belongs to a municipal prompt care unit (UPA) and has a doctor, a nurse and a nursing technician who attend approximately 6 patients/day; these are mainly elderly patients with chronic and multi-pathological diseases admitted due to a worsening of their clinical condition. In this unit the patients usually stay at most 24h, as they are transferred to other services if they need specialist care.

Data collection – carried out between October 2016 and February 2017 – was based on semi-structured face-to-face interviews with patients and relatives. The interviews were conducted between one and just over 24h after the patient was admitted to the ED and lasted between 16 and 65min. Although some interviews were brief, a relationship of trust was fostered from the first contact between the researcher and the respondent, and therefore the respondents talked openly about their experiences. There were only 2 inpatient interviews that lasted less than 30 minutes, and this was due to the delicate health situation of the respondents. The interviews began with the following question: “I would like to know what your perception is of the fact that the family is not allowed to be present in the emergency room during health care”.

The sample comprised 30 participants: 15 patients and 15 family members. The inclusion criteria for patient participation were being over 18 years of age, being under observation/admitted to the ED of one of the 2 participating units and presenting no trauma, aggravation or illness that would prevent interpreting and/or answering the questions. The inclusion criteria for family members were being over 18 years old and with an affective bond with a patient attended in the ED. Patients and relatives who were not in a psychological or emotional condition to answer the questions were excluded.

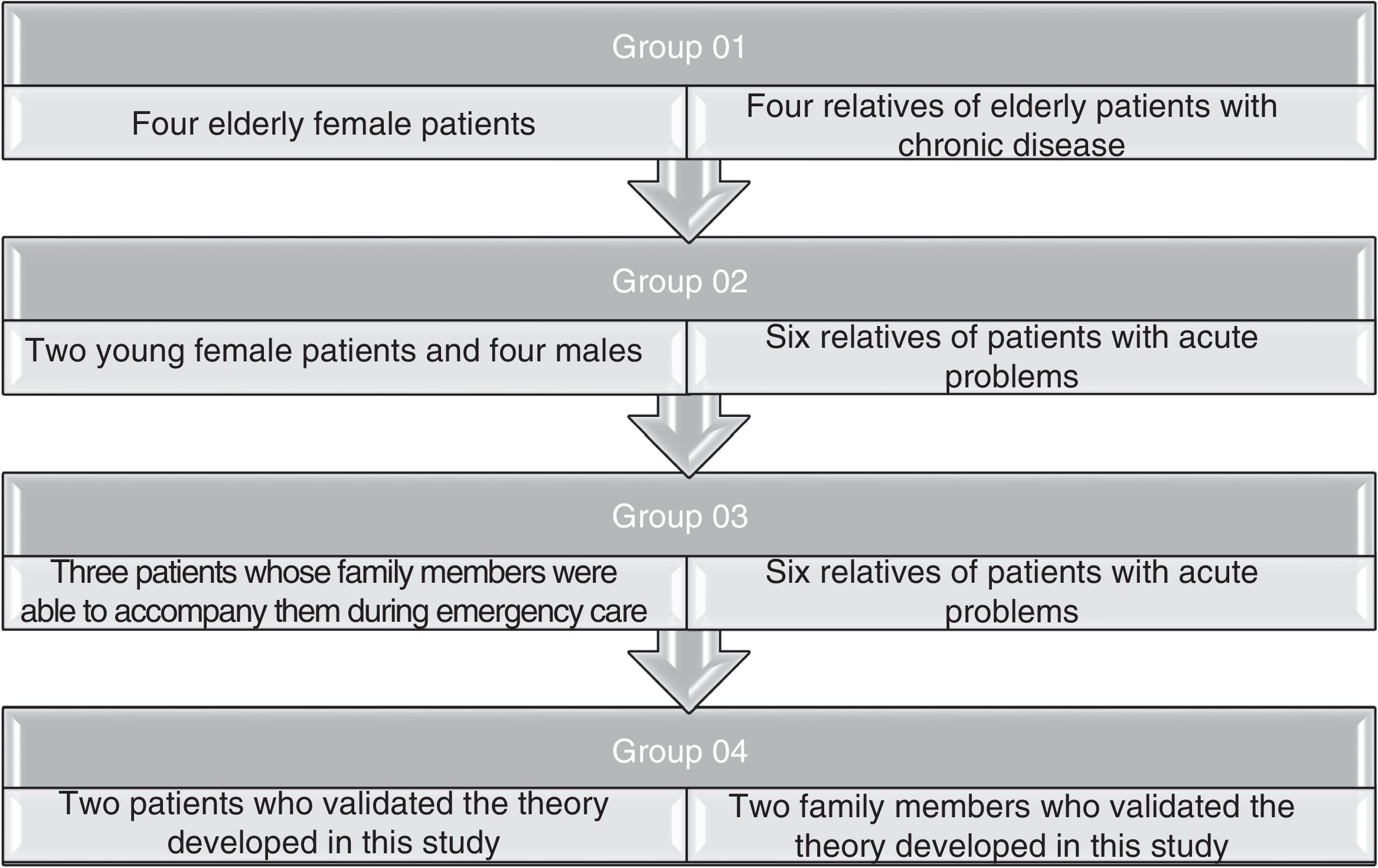

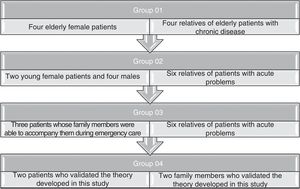

Following the premises of Grounded Theory,24 theoretical sampling was used to guide the data collection until theoretical saturation was reached with a total of 30 participants. Initially, intentional sampling was used, which later evolved into theoretical sampling according to the emerging theory. The theoretical sampling groups are shown in Fig. 1.

Through the constant comparative method, the interviews were held concomitant with the data analysis and formation of the theoretical sampling groups. All the interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed, edited, coded and compared one by one. The text of each interview was transcribed and read simultaneously to gain an overall understanding of its content and then begin the open-ended coding process supported by the QDA Miner® software. During this phase, the construction of memoranda and diagrams was initiated.

As the analytical process progressed, axial coding was initiated, with comparison between interview codes. This facilitated grouping these codes by conceptual similarities and differences, which allowed identification of the conceptual properties of the categories through establishing temporal concepts. A posteriori, selective coding allowed densification of categories and identification of the central category.

Following the recommendation of Corbin and Strauss,24 theoretical saturation of the data was reached, and therefore the search for new respondents discontinued when it was observed that the information was repeated or when there were no new elements from their accounts towards a better understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Regarding the quality and rigour of the research, it should be noted that the data analysis was carried out in a first phase by the principal researcher (MSB), who used reflexivity and prior suspension of ideas throughout the analysis process. Later, the results of the analysis were shared with the rest of the research team, and when there were doubts or contrasts in the interpretation of the data, the team discussed the analytical and interpretative process until a consensus was reached. In this way, confirmability was achieved in the data analysis. In addition, triangulation of data sources through the use of theoretical sampling helped to achieve an optimal degree of transferability. In other words, obtaining information from the patients and families attended in the different emergency units, of different age and sex, and with different diagnoses, provided a diversity of circumstances. These strategies were important to ensure the methodological rigour of this research.

With respect to ethical aspects, this study was developed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council of Brazil, with approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the signatory institution. The right to free participation and anonymity was guaranteed to all respondents, who read and signed their informed consent. The principles of beneficence, non-maleficence and justice were also respected. In the presentation of the results, the participants were identified by the theoretical sampling group to which they belonged, followed by the word “patient” or “family member” and also by the sequential number of the interview.

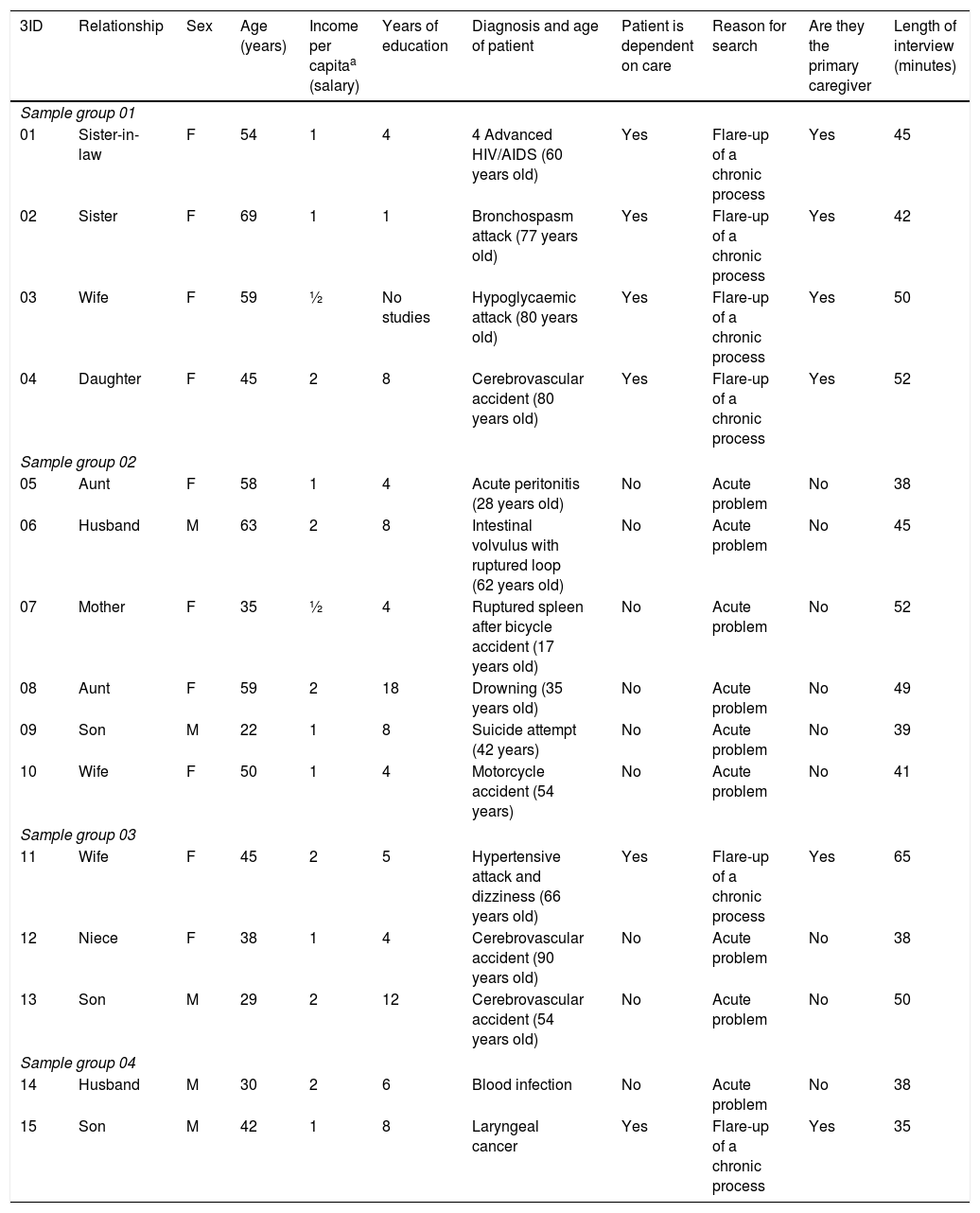

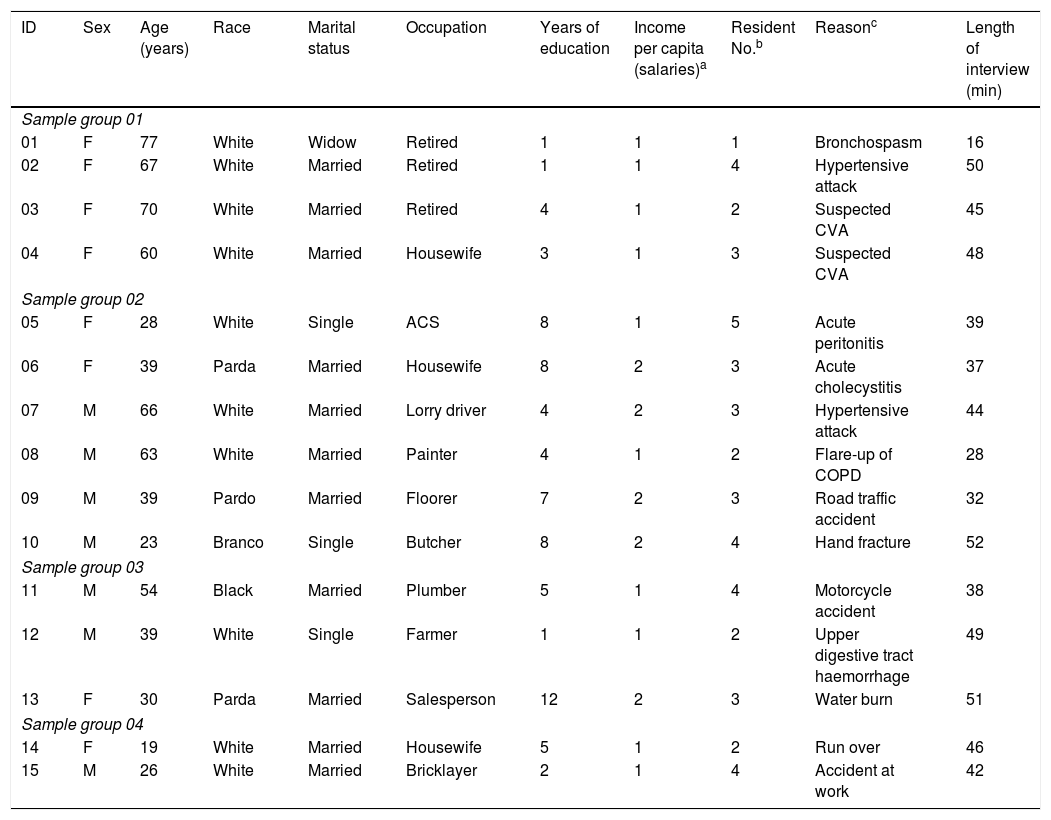

ResultsA total of 30 people participated, of whom 15 were patients and 15 relatives, and their characteristics are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Social characteristics of the family members. Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2017.

| 3ID | Relationship | Sex | Age (years) | Income per capitaa (salary) | Years of education | Diagnosis and age of patient | Patient is dependent on care | Reason for search | Are they the primary caregiver | Length of interview (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample group 01 | ||||||||||

| 01 | Sister-in-law | F | 54 | 1 | 4 | 4 Advanced HIV/AIDS (60 years old) | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 45 |

| 02 | Sister | F | 69 | 1 | 1 | Bronchospasm attack (77 years old) | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 42 |

| 03 | Wife | F | 59 | ½ | No studies | Hypoglycaemic attack (80 years old) | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 50 |

| 04 | Daughter | F | 45 | 2 | 8 | Cerebrovascular accident (80 years old) | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 52 |

| Sample group 02 | ||||||||||

| 05 | Aunt | F | 58 | 1 | 4 | Acute peritonitis (28 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 38 |

| 06 | Husband | M | 63 | 2 | 8 | Intestinal volvulus with ruptured loop (62 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 45 |

| 07 | Mother | F | 35 | ½ | 4 | Ruptured spleen after bicycle accident (17 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 52 |

| 08 | Aunt | F | 59 | 2 | 18 | Drowning (35 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 49 |

| 09 | Son | M | 22 | 1 | 8 | Suicide attempt (42 years) | No | Acute problem | No | 39 |

| 10 | Wife | F | 50 | 1 | 4 | Motorcycle accident (54 years) | No | Acute problem | No | 41 |

| Sample group 03 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Wife | F | 45 | 2 | 5 | Hypertensive attack and dizziness (66 years old) | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 65 |

| 12 | Niece | F | 38 | 1 | 4 | Cerebrovascular accident (90 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 38 |

| 13 | Son | M | 29 | 2 | 12 | Cerebrovascular accident (54 years old) | No | Acute problem | No | 50 |

| Sample group 04 | ||||||||||

| 14 | Husband | M | 30 | 2 | 6 | Blood infection | No | Acute problem | No | 38 |

| 15 | Son | M | 42 | 1 | 8 | Laryngeal cancer | Yes | Flare-up of a chronic process | Yes | 35 |

F: female; ID: identification; M: male; HIV/AIDS: human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Social characteristics of the patients. Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2017.

| ID | Sex | Age (years) | Race | Marital status | Occupation | Years of education | Income per capita (salaries)a | Resident No.b | Reasonc | Length of interview (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample group 01 | ||||||||||

| 01 | F | 77 | White | Widow | Retired | 1 | 1 | 1 | Bronchospasm | 16 |

| 02 | F | 67 | White | Married | Retired | 1 | 1 | 4 | Hypertensive attack | 50 |

| 03 | F | 70 | White | Married | Retired | 4 | 1 | 2 | Suspected CVA | 45 |

| 04 | F | 60 | White | Married | Housewife | 3 | 1 | 3 | Suspected CVA | 48 |

| Sample group 02 | ||||||||||

| 05 | F | 28 | White | Single | ACS | 8 | 1 | 5 | Acute peritonitis | 39 |

| 06 | F | 39 | Parda | Married | Housewife | 8 | 2 | 3 | Acute cholecystitis | 37 |

| 07 | M | 66 | White | Married | Lorry driver | 4 | 2 | 3 | Hypertensive attack | 44 |

| 08 | M | 63 | White | Married | Painter | 4 | 1 | 2 | Flare-up of COPD | 28 |

| 09 | M | 39 | Pardo | Married | Floorer | 7 | 2 | 3 | Road traffic accident | 32 |

| 10 | M | 23 | Branco | Single | Butcher | 8 | 2 | 4 | Hand fracture | 52 |

| Sample group 03 | ||||||||||

| 11 | M | 54 | Black | Married | Plumber | 5 | 1 | 4 | Motorcycle accident | 38 |

| 12 | M | 39 | White | Single | Farmer | 1 | 1 | 2 | Upper digestive tract haemorrhage | 49 |

| 13 | F | 30 | Parda | Married | Salesperson | 12 | 2 | 3 | Water burn | 51 |

| Sample group 04 | ||||||||||

| 14 | F | 19 | White | Married | Housewife | 5 | 1 | 2 | Run over | 46 |

| 15 | M | 26 | White | Married | Bricklayer | 2 | 1 | 4 | Accident at work | 42 |

ACS: community health worker; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F: female; ID: identification; M: male.

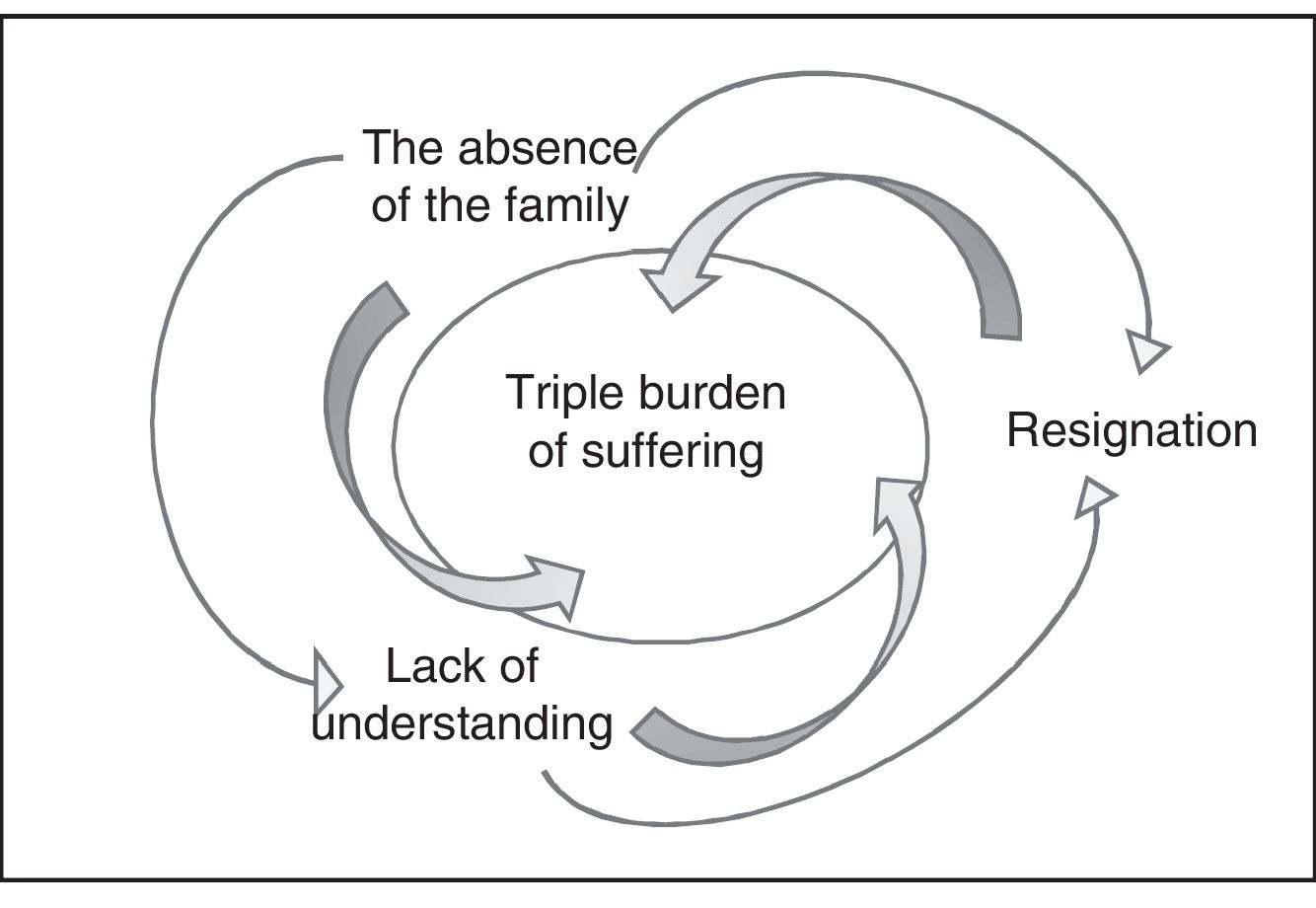

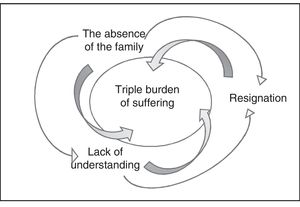

Below are the results of this grounded theory study whose central category is: “The absence of the family in emergency care contributes to suffering in patients and family members” and related to the following 3 main categories: “suffering through the absence of the family; “suffering from lack of understanding of absence of the family”; and “suffering from resignation to absence of the family”.

Absence of family in emergency care carries a triple burden of sufferingExperience of the process of family absence during emergency care is distressing to both patients and families. The concept of suffering is characterised by the negative impact from the physical separation of the patient from their family, such as exacerbation of doubt, uncertainties, fear and anguish, as materialised through the verbal account of suffering, crying and facial and body expression of worry and concern, for both (patients and families). This suffering is intensified by the lack of understanding about the reasons for family exclusion and by being resigned to the situation (Fig. 2). In other words, patients and families accept the decisions of the professionals, although they do not understand the real reasons behind excluding family members from emergency care, and prefer to “follow orders” to ensure that the patient does not suffer reprisals or neglect by the healthcare team.

In this sense, there is a symbolic power that the unit and its professionals project onto patients and families related to a passive attitude towards relatives not being allowed to be close to the patient during emergency care. Not opposing this situation causes them more suffering, since the feeling of resignation is what keeps them inactive in facing not being able to stay together as a family.

Suffering though absence of familyAbsence of family from emergency care has negative consequences for both patients and families. The consequences for patients include the exacerbation of doubts regarding care and worsening of the suffering already experienced as a result of acute and severe illness. ...] When it comes to pain and suffering, there's nothing worse than being and seeing yourself alone, with no one from your family. Because you’re having a hard time and you come here to this room alone, with strangers, you‘re in pain, not knowing what's going to happen. It's very difficult! (G2, Patient 06).

Not being able to be close to their loved one during emergency care also has consequences for the family members. Anxiety, worry, pessimism about the situation are part of this experience, especially when the family members lack information about the patient's clinical picture and prognosis. ...] People are there outside and they’re worried, nobody called me to talk, nobody gave me information, I came out here [to the unit's reception] and here I am, not knowing anything else. People stay out there, wondering: My God, will [the patient] be all right? That's why I would like to be with her (G1, Family member 02 – sister).

By remaining outside the ED, the family member has no possibility to have eye contact with the patient, to accompany him/her, and understand the care received, which contributes to the suffering and the desire to be closer. ...] While I was looking at him lying down, I knew that everything was fine, but when they went in with him [to the ED] I knew nothing more. I even thought they had taken him to the ICU, because the nurse told me he might have had a stroke. What if this really happened? It hurts so much, I didn’t want to be away from him [...] (G3, Family member 11 – wife).

On occasion, when patients cannot count on the presence of family members in emergency care, they report feeling that their rights are being violated. ...] my wife stayed here for a while, then she was thrown out. I think it's the family's right to be here, to know what's going on, to question what's being done. But no one respects this right, they [the professionals] just come in and separate us, one on each side. Whoever is in here [the patient] suffers as well as whoever's out there [the family member] (G3, Patient 13).

In this particular context, the feeling of “a right violated” by the separation of patients and family members is identified as generating reciprocal suffering. Thus, there is suffering not only because of the physical separation of family member and patient or because of the lack of information, but also when it is perceived that one's wishes and rights, such as being close to one's family in a moment of crisis, are being disregarded. Given the experience of a “right violated”, patients believe it is necessary for health professionals to use strategies that allow families, at least for a period of time, to be with their loved ones in the ED or provide other means of communication between them, such as the use of mobile phones within the ED. [...] She can’t come during visiting hours because they’re only 30 minutes. We live far away and due to the accident, we’re now without a vehicle. If she could come and stay, for example, from three to eight in the afternoon and then return home, it would be better, easier (G2, Patient 09). [...] I can’t even use my mobile phone in here, the staff won’t let me. My intention was to call home. My family, for example, don’t know what's going on with me and I could call them, but the professionals don’t like it (G2, Patient 06).

It is observed that patients and families experienced negative consequences from the absence of the family in emergency care, especially the exacerbated suffering of both, because they felt their rights were violated. However, they themselves think of strategies that would allow families to be more informed about the patient's clinical progression to be present at certain periods of time in the ED.

Suffering due to a lack of understanding of the absence of the familyThe absence of the family, in addition to triggering doubts regarding patient care and prognosis, contributes to a lack of understanding about the reasons for the professional's decision not to allow them to be with the patient in the ED. This decision increases the suffering of patients and families: [...] nobody came to explain anything to me, the nurse just said I should wait in the corridor. So, I don’t know why I can’t stay! (G2, Family 09 – child). Very stressed! We didn’t know anything; I don’t know why the family can’t stay here (G2, Patient 09).

Through failing to understand the reasons that legitimise professional behaviour in not allowing the family to be present, patients and family members consider that their situation may be influenced: (a) by the fear that family members, when accompanying the patient, may become nervous or have a bad time and may hinder the care of the patient; (b) by the high demand of patients in the ED that would result in a large number of accompanying persons, making the work of professionals difficult; (c) due to compliance with institutional regulations, protocols or rules that forbid the family to be present; (d) due to the personal sympathies and attitudes of each professional towards the families; and (e) due to the assessment by professionals of an ideal profile for the family member, i.e., being calm and immune to the situation. I believe that the professionals don’t let us stay because of the procedures that are carried out there, that we can’t participate in or, sometimes, because they believe that we will hinder the service, the care of the doctors. I also think that they suspect that people could have a bad time in there, complicating the situation further (G3, Family member 13 – child). ...] if everyone were able to have a companion, it would be crowded [the SU]. To such a point that the professionals’ work would be more difficult (G2, Patient 06). When they talk about family in here, it seems that the professionals want the family to be at a distance and also, to distance us from our family, they don’t have much sympathy (G3, Patient 11). If the professionals think that the family member is sick, restless or aggressive, they don’t let him/her stay (G2, Family member 08 – aunt).

Although they do not fully understand the reasons preventing the presence of the family in emergency care and despite identifying that this situation leads to the intensification of suffering, patients and relatives, by relativising and assuming the role and knowledge of professionals, understand some situations and some reasons why the presence of the family in the ED is not allowed.

Suffering due to resignation to the absence of the familyThe professional decision not to allow the presence of the family in the ED causes suffering to both family members and the patient. They are also resigned to the fact that they cannot do anything against it, which intensifies their suffering. Some of the signs that showed the resignation of the patient and their family were: keeping silent, not intervening and moving away, leading to their not expressing concerns and not interacting with the setting and its actors. A symbolic power is perceived that the health unit and its professionals possess over relatives and patients. This symbolic power results from the physical, cultural and emotional distancing of the social actors, i.e. family–patient–professionals, which in turn is reflected in impersonal communication, full of scientific terms and which does not address the concerns and needs of patients and families. This inhibits any attempt to contradict the decisions imposed by professionals. Therefore, resignation is a consequence of this symbolic power and results in a perception of defencelessness on the part of patients and families. This perceived helplessness occurs when patients and their loved ones identify that help, information or protection by professionals is not sufficient. I don’t know why the family can’t stay. All I know is that it's unfair, it's sad, it's our right. But it's okay, we’re in a place that is not ours and we have to understand (G2, Patient 08). Do what? We can’t do anything, there's no way to disobey [silent and lowering her eyes] (G1, Family member 02 – sister).

This resignation is also a consequence of the fact that patients and families feel alienated from the emergency department, they do not feel welcome and included in the care setting. Similarly, for family members the ED is a space that belongs to health professionals, since the presence of patients is temporary, and families are not welcome. Thus, they admit that they must comply with the rules imposed. The hospital is where they work, the rules are there to be followed, only, for them, there are lots of patients (G2, Family member 08 – aunt). Here in the emergency room where she is, we know that no one can stay, you can only visit. Actually, the professionals say that it is not necessary. We suffer more, but we accept it. It's their space (G2, Family member 05 – Aunt).

The resignation of some relatives is related to the fear that, by questioning the professionals’ behaviour and expressing their desire and right to be with their loved one, there may be reprisals in the care of the patient. Everyone wants to stay with their relative, but are you going to say so? Then someone gets angry and our relative pays for it (G1, Family member 02 – sister).

Patients and relatives perceive the emergency department as a space wrapped in symbolism. The patient's fear of reprisals by the professionals – people outside their family circle, with a high level of academic training and at that time, directly responsible for the life of the patient – as well as their understanding the place as alien and governed by strict rules, make the ED and its professionals a place with notorious symbolic power over the temporary users of that setting: patients and relatives.

Therefore, the families accept that the decisions of the professionals, although contrary to their personal interests and needs, are the most appropriate and effective, and questioning in this regard is not allowed. Thus, families and patients do not oppose and are resigned to not being present in emergency care, which increases their suffering.

DiscussionThe findings of this study show how patients and families experience the absence of the family in emergency care. The discourses are convergent and complementary, demonstrating that both relatives and patients internalise, assume and abide by the phenomenon in a similar way. In this sense, a triple burden of suffering in family members and patients is identified. Suffering, in this particular context, is a natural consequence of the patient's own acute and severe illness, which is further enhanced by the family's absence from emergency care. Suffering, in turn, brings with it fears, worries, uncertainties and distress in patients and families. These findings coincide with the literature that suggests that, as a general rule, health emergencies trigger intense suffering in the person and their families, since injuries and/or diseases generate physical pain, as well as the doubts about the disease itself, treatment and prognosis that generate feelings of concern and fear.7,9,25

A research study conducted with 18 family members of patients who survived life support interventions in an accident and emergency department in Hong Kong, also corroborates the findings of the present study on the suffering experienced by relatives due to the absence of the family in emergency care.23 In this study, it was shown that family members, when kept distant, showed intense suffering, mainly due to the lack of information about the patient's state of health and not being able to emotionally support their loved one.23 Likewise, studies conducted in Brazil9 and the United States7 with patients who received care in the emergency department found greater suffering among those who were distant from their families.

Despite the impact and suffering typical of emergency situations, family members report a strong desire to be close to their relative, as they perceive this as a universal family right that cannot be violated25; and more importantly, when they are present, families, in most cases, express lower levels of anxiety and greater well-being.26,27 The study by Compton et al. in 2009,28 however, revealed symptoms of post-traumatic stress in family members due to the lack of a support intervention for family members after the death of the patient.

Another relevant finding is that the respondents did not understand the specific reasons that prevented the presence of the family in the ED. However, the patients and relatives tried to put themselves in the place of the health professionals and acknowledged possible reasons for not being allowed to be present. For example, they believe that some family members might have a hard time witnessing procedures, which would hinder care delivery since the professionals might have to divide their care between the patient and the family member. Therefore, for the family to be present in a satisfactory manner, it is necessary for the professional who will accompany them in the ED to prepare them beforehand.29 The fact that the same professional prepares and accompanies the family members helps to create a bond of trust between them. In addition, preparation – which consists of preparing the family member for scenes they might encounter when entering the ED – minimises possible traumatic effects and promotes their emotional well-being.22

Today, for clinical practice to be well received by families, professionals must be technically and emotionally prepared,5 since it is their responsibility to provide information to family members, explain events during care, ensure wellbeing and accompany the family member outside the unit if they show signs of suffering.1 To that end, education and awareness of the presence of the family and the elimination of unfounded professional fears are a first and important step to ensure that clinical practice is based on evidence and not on personal preferences.15 We suggest that this professional preparation be developed with those who already make up the teams of the emergency units and by the managers of the services themselves, in order to avoid increasing costs in the units and to encourage adherence to practice that favours the presence of the family.

Another reason identified in this study for the absence of the family in the ED is the excessive number of patients in these units. In fact, different research studies with health professionals point to a lack of staff and/or physical space as the main reasons for rejecting the presence of the family in emergency units.13,15,19 Professionals want an uncrowded environment, without disturbance or distraction.13,15 The participants in the present study also coincided in their desire not to hinder or interfere with the performance of the healthcare team. It is therefore necessary to restructure the emergency departments to provide space to promote policies of family presence, especially during care of critical patients and resuscitation manoeuvres. Professionals working in emergency units must offer comprehensive care that covers the basic needs of the critically ill patient and the risk of death, as well as the support and information needs of accompanying family members.

According to the patients and families in this study, professionals exclude the family in the belief that family members have an “ideal profile”. That is, when professionals perceive that accompanying relatives are nervous and emotionally vulnerable, they are considered “unfit” to be present in the ED. In this regard, a study stated that family members understand the need to demonstrate self-control and “appropriate behaviour” in the ED, since otherwise they may harm the patient and negatively interfere with healthcare.23 Thus, patients and relatives believe that the presence/absence of the family seems to be directly related to their ability to manage a stressful event. This may relate to the constructed social concept of the “good patient” – transferred to the concept of “good companion” – characterised by passive and positive behaviour towards professionals.30

Along these same lines, an interesting contribution in this study is the participants’ resignation to the absence of their families. This feeling seems to emerge due to the symbolic power represented by the health team and the characteristics of the emergency services themselves. In this sense, research with Australian professionals showed that they claimed ownership of the patient, believing they had the maximum right and authority to “allow” or “prevent” the presence of the family.15 Furthermore, the rigid rules on excluding the family in the context of critical care31 and emergencies result in a lack of autonomy for families and impersonal and bureaucratised care.32,33

LimitationsOne of the limitations of this study is that most of the family members interviewed were female despite the attempt to include more male relatives. However, during the time interval in which the data were collected, most of the accompanying persons were women, and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution as they present a predominantly female view of the experience of family absence in the emergency department.

The interviews were performed in the emergency departments themselves, during the immediate experience of the critical situation, without the participants having time to reflect on the experience. It may be that the critical situation limited the complete expression of feelings and experiences by the participants and, on the other hand, that a greater perception of suffering was observed due to the situation being immediate. Therefore, and in order to compare and complete the findings of this study, we recommend that future research investigate the experience of patients and families of the presence/absence of family members in the emergency departments retrospectively.

ConclusionThe accounts of the patients and families who experienced emergency care without the presence of family show exacerbated fears, doubts and sadness about family separation. The families, despite not understanding the reasons preventing them from accompanying their loved one in the ED, accept with resignation the decision of health professionals. However, this causes triple suffering in the family unit characterised by the emergency situation itself, the absence of the family and the helplessness of not knowing the reasons for this separation. Added to this is the lack of acceptance of the family in the emergency department and a distant relationship with the professionals that have a negative effect on experiences in times of intense family crisis.

In light of these findings, we see a need in nursing and medical student education to promote training in communication and therapeutic relationship skills through simulation. Likewise, continuous training of professionals in emergency departments should be fostered to implement family-centred welcome strategies and multi-professional accompaniment, towards alleviating the suffering of the patient and his/her family. In addition, we recommend the development of institutional policies and standards that allow professionals to welcome families into emergency units. This is to ensure that clinical practice and hospital standards are based on the best evidence. A change in the organisational and regulatory structure of emergency departments is also required to improve much-desired person and family-centred care.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

FundingCoordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil. Process number: 99999.003873/2015-03.

Please cite this article as: Barreto MS, Garcia-Vivar C, Dupas G, Misue Matsuda L, Silva Marcon S. La ausencia familiar en la atención de urgencia conlleva sufrimiento en pacientes y familiares. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:71–81.