School refusal behavior refers to the avoidance of a child attending school and/or persistent difficulty staying in the classroom throughout the school day. Based on a review of the scientific literature, the aim of this study is to describe the current state of research on school refusal, differentiating between the findings and progress made in Spain from those achieved in the international field. For this purpose, the significance of this phenomenon, in addition to associated risk factors and variables, will be reviewed in the child and youth population. In turn, the commonly used assessment methods and most recommended treatment proposals, mainly based on cognitive behavioral therapy, are discussed. The results reveal several gaps and subjects for debate in some areas of knowledge about school refusal behavior, with differences being found between Spanish and international studies. In conclusion, future studies and challenges in this field are required.

El comportamiento de rechazo a la escuela se refiere a la negativa de un niño a asistir al centro educativo y/o la dificultad persistente para permanecer en el aula durante toda la jornada escolar. A partir de la revisión de la literatura científica, es objeto de este trabajo describir el estado actual de la investigación sobre el rechazo escolar, diferenciando los hallazgos y avances alcanzados en España de aquellos conseguidos en el ámbito internacional. Para ello, se revisará la trascendencia de este fenómeno en población infanto-juvenil y los factores de riesgo y variables asociadas. A su vez, se discutirán los métodos de evaluación generalmente utilizados y las propuestas de tratamiento más recomendadas, basadas, principalmente, en la terapia cognitivo-conductual. Los resultados obtenidos revelan diversas lagunas y debates en algunos campos de conocimiento sobre el rechazo escolar, con diferencias en la investigación española respecto a la internacional. A modo de conclusión, se proponen futuras líneas de investigación y desafíos en este campo.

School refusal behavior refers to the child's refusal to go to school and/or persistent difficulty to remain in class for the entire school day (Kearney & Silverman, 1999), which manifests in children and adolescents from 5 to 17 years of age (Kearney, Cook, & Chapman, 2007). Therefore, school refusal covers all the cases of children who refuse to attend school. Nevertheless, at this point, authors’ discrepancies emerge. On the one hand, Heyne, King, Tonge, and Cooper (2001) propose differentiating children who leave school with paternal consent and with emotional or anxious manifestations from those who “play hooky,” also known as truancy. On the other hand, this differentiation does not satisfy all the researchers, so outstanding specialists in this field of study propose the construct of the behavior of school refusal to include all the cases of school absenteeism within this category (Kearney, 2007, 2008).

Given this controversy in the use of terms, concepts such as school phobia, school anxiety, or absenteeism have been used as synonyms, favoring the emergence of discussions on the conceptual delimitation of this phenomenon (Kearney & Graczyk, 2014). However, the term school refusal is recommended, as it takes into consideration the causal heterogeneity of the problem and is a broader and more inclusive concept, as noted by National Association of School Psychologists (NASP; Bragado, 2006; Brand & O’Conner, 2004; Kearney, 2007). In the same vein, the construct school refusal has shown its relevance in this research field during the past few years, because when performing a bibliographic search of international databases such as PsycINFO, ERIC or the Web of Science, we found that, during the 2010-2014 period, the number of works located with the term school refusal is twice as high as the results compared to the search strategy school phobia. Thus, currently, according to the NASP, the concept of school phobia has been relegated by that of school refusal.

With regard to the nosological entity of school refusal, it is noted that it is not classified as an independent diagnostic category in the international systems classification, either in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013) or the tenth review of the International Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10) of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1992). Nevertheless, school refusal may be linked to diverse mental health disorders, such as: (a) separation anxiety disorder (SAD), (b) generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), (c) oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), (d) schooling-related events (being the target of ridicule, being criticized in class in front of classmates, being sent to the director, taking exams), or (e) depression (Kearney & Albano, 2004).

One of the features of school refusal is the heterogeneity of the affected population, both at a causal level, that is, the reasons for their behavior, and the response behavior. Therefore, it is difficult for researchers to establish a single model of classification to determine whether a child suffers from school refusal. In turn, the DSM-V (APA, 2013) does not distinguish between the different subtypes of school refusal, making the categorization of this phenomenon even more difficult. However, over time, diverse systems have been formulated, among which is the functional model, which is the most consolidated in the study of school refusal behavior.

From this functional model, we intend to answer the question: Why does my child not want to go to school? This model focuses on examining the reasons of youths who suffer school refusal for not wanting to attend school. The instrument School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R; Kearney, 2002a) assesses school refusal behavior based on the functional model. According to this approach, there are four main reasons that justify the behavior of school refusal (Kearney & Spear, 2014):

- •

Avoiding the negative affect provoked by the stimuli of situations related to the school setting (e.g., “How often do you try to avoid going to school because if you go, you feel sad or depressed?” or “How often do you have negative feelings towards school (e.g., scared, nervous or sad) when you think about school on Saturday or Sunday?”).

- •

Escaping from social aversion or evaluation situations (e.g., “If it were easier for you to make new friends, would it be easier for you to go to school?” or “How often do you avoid other people at school, in comparison with other boys/girls of your age?”).

- •

Seeking significant others’ attention (e.g., “How often would you prefer your parents to teach you at home instead of your teacher at school?” or “Would it be easier for you to go to school if your parents went with you?”).

- •

Seeking tangible reinforcements outside of the school setting (e.g., “How often do you refuse to go to school because you want to have fun out of school?” or “Do you prefer to do things out of school more than most boys / girls of your age?”).

According to Kearney and Spear (2012), the first two functions are characterized by negative reinforcement because the behavior is reinforced by the avoidance of unpleasant situations (e.g., anxiety and/or school phobia), whereas the last two functions are positively reinforced, as behavior outside of the school setting is reinforced by attention or rewards (e.g., absenteeism).

With this work, we intend to provide an exhaustive review of the current state of school refusal research. To this end, a distinction is made between the scientific advances developed both at national and international levels to date, concluding with the proposal of new challenges and emerging lines of research in the field of school refusal.

Research of school refusal in SpainContextualization and transcendence at the national levelInterest in knowing students’ attitudes towards the educational center is currently considered one of the most influential factors in academic achievement, as well as in the presence of school refusal behaviors. Accordingly, the 2012 Spanish PISA (Program for the International Assessment of Students) report has considered it necessary to include in its latest edition a series of issues aimed at assessing the degree of student satisfaction with their educational center. Sixty-five countries participate in this program, of which 34 belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) among which is Spain. After successive negative results, which, according to PISA, place Spain among the countries below the OECD average in Mathematics, Reading, and Science, it is necessary to analyze the situation in Spain with regard to the factor evaluated by PISA referring to student well-being at school. Students’ attitudes towards school were assessed with variables such as punctuality and absenteeism, their sense of belonging to the school, and the disciplinary climate. The results found were obtained from 15-year-old students. With regard to unjustified absenteeism from school, the OECD mean is at 15%, a percentage corresponding to students who report having missed at least one school day in the past two weeks. Similar percentages were obtained by the majority of countries of the European Union, except for Spain, which, at 28%, reached one of the highest percentages of students who reported missing class. Specifically, 24% missed between one or two days, 3% between three or four days, and 1% missed more than five days. Noteworthy is this report's emphasis on the influence of the socioeconomic settings in school refusal behavior. The results indicate that, in Spain, 37% of absentee students come from disadvantaged environments, compared to 19% who are raised in advantaged environments. Regarding the lack of punctuality, there were no large differences compared with the OECD mean, indicating a decrease in the number of tardy students at the national level with regard to the results of PISA in 2003 (OECD, 2003). On the other hand, Spain stands out as one of the OECD countries among which the students feel more integrated within the social group.

From this report, it is clear that the main problem is the percentage of students who do not attend school for unjustified reasons, and we are faced with an adolescent population at risk of not fully developing their academic, personal, and social potential (Carroll, 2010; Henry, 2007; Yahaya et al., 2010).

Risk factors and other variables related to school refusal in SpainThe study of school refusal behavior and its relation with other variables is a field of research with few precedents at the national level. Santacruz et al. (2002) indicate in their research, quoting Elliot (1999), that school refusal is usually more highly associated with SAD, GAD, and specific phobias (school phobia, social phobia) during childhood, whereas in adolescents, it can also be related to depression. Nevertheless, we found no studies carried out with Spanish samples specifically assessing school refusal as a predictor of other constructs of psychoeducational interest. We note that the use of the term school refusal in this area has been mostly employed alluding to a sociometric type in which the child is rejected by his/her peers at school (Cerezo, 2014; Estévez, Martínez-Ferrer, & Jiménez, 2009; García-Bacete et al., 2013; García-Bacete, Sureda, & Monjas, 2010; Inglés, Delgado, García-Fernández, Ruiz-Esteban, & Díaz-Herrero, 2010).

Research on the behavior of school refusal in this country does not present the firm conception defended internationally by authors like Kearney (2008), who defends the use of a construct that includes diverse degrees of school absenteeism. On the basis of this statement, the works carried out by Spanish researchers focused independently either on the study of anxiety and school phobia or on school absenteeism.

The construct school anxiety or stress is defined as a set of unpleasant physical and cognitive symptoms that appear as a response to global and specific school stressors (Kearney et al., 2007). Thus, school anxiety can be defined as a pattern of anxious responses elicited by stressful school situations that the student perceives as dangerous or threatening (García-Fernández, Inglés, Martínez-Monteagudo, & Redondo, 2008).

The term school phobia refers to a specific situational phobia, in this case, to the educational institution, and it is considered a subcategory within the general behavior of school refusal (García-Fernández, Inglés, Marzo, & Martínez-Monteagudo, 2014). It consists of a serious difficulty to attend or remain in the educational center due to an irrational and excessive fear of school situations such as being evaluated, fear of the teacher or the peers (García-Fernández et al., 2008). In recent years, it has been shown that school avoidance is not only the result of the presence of a specific phobia but that it may also be due to various causes such as fear of separation from loved ones (mainly linked in childhood to the figure of the parents and which could result in a diagnosis of SAD), the fear of certain circumstances related to the school, such as being the target of ridicule or talking in public in front of the class, situations that could indicate a diagnosis of a specific or social phobia, and problems of generalized anxiety or depression.

Regarding school truancy, it refers to repeated unjustified absence, not based on anxiety and performed without paternal consent (Kearney & Bensaheb, 2006). This is a multifactor problem, as there are different risk factors that can lead to this action. Among them are personal variables, such as personality or lack of interest in the educational institution, as well as the influence of the family environment, the measures carried out by the school or institute, and the relations established with the peer group (Sáez, 2005). Possible consequences or factors associated with this problem are the presence of delinquent behaviors, drug or alcohol abuse, and problems in the family environment (Corbí & Pérez-Nieto, 2013; Duarte & Escario, 2006).

Assessment of school refusal in SpainAfter performing an exhaustive review of the instruments to specifically assess school refusal, no prior studies were found validating the assessment instruments of school refusal for application in Spanish childhood-youth samples. The following scales were considered specific measures to assess school refusal behavior: the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised for Children (SRAS-R-C, Kearney, 2002a; SRAS, Kearney & Silverman, 1993), the Feelings of School Avoidance (FSA, Watanabe & Koishi, 2000), the School Avoidance Scale (SAS, Fujigaki, 1996) and the School Refusal Personality Scale (SRPE, Honjo et al., 2003). These will be analyzed in a section after the present review, focused on the analysis of the instruments to assess school refusal from an international perspective and in which its investigations reach numerous countries. Among the instruments is the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised-Child (SRAS-R-C), internationally considered a referent instrument to assess school refusal (Haight, Kearney, Hendron, & Schafer, 2011; Lyon, 2010). As it is not validated in Spanish sample, there are no available epidemiological data to allow us to know the incidence of this problem in Spain. Nevertheless, school refusal behavior has been assessed nationally as a subcategory within other instruments such as:

- •

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV-C; Silverman & Albano, 1996) in the Spanish version (Sandín, 2002). This is a semistructured interview aimed at a population between 7 and 17 years of age, assessing anxiety disorders based on the diagnostic criteria established by the DSM-IV. Among the disorders measured (SAD, dysthymia, major depressive disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, behavior disorder, oppositional defiant disorder), it includes questions about school refusal within SAD. The questions about the assessment of this phenomenon are of the type, “Do you get nervous or scared because you have to go to school?”, “Do you stay at home and don’t go to school because you get scared or nervous there?” or “Have you ever run away from school or left early because you are better off at home?”. With regard to its psychometric properties, test-retest reliability varies depending on the study from .61 to 1. In the work of Silverman, Saavedra, and Pina (2001), the analyses reported an acceptable test-retest reliability in children between 7 and 16 years (k = .61-.80), in parents (k = .65-1.00) and combined (k = .62-1.00). This instrument has been applied in Spanish sample both in case studies to treat an adolescent with GAD (Olivares, Piqueras, & Rosa, 2006) and in adult population with panic disorder and high sensitivity to anxiety (Osma, García-Palacios, Botella, & Ramón, 2014).

- •

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999). This instrument is a self-report questionnaire with 41 items assessing the frequency of anxious symptoms, aimed at a population between 8 and 18 years. Subjects rate the frequency with which they have experienced each symptom, indicating their response on a Likert-type scale with three response options (0 = never or almost never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = frequently, almost always). The total score is the sum of the responses, which can range from 0 to 82. The authors indicated an optimal cut-point of 25 for clinical population of the United States. Birmaher et al. (1999), in their factorial study, found five factors for this questionnaire: (a) Panic/somatic disorder (PD); (b) Generalized anxiety (GAD); (c) Separation anxiety (SAD); (d) Social phobia (SPD); and (e) School phobia. Four of the five factors are clearly linked to the anxiety disorders presented in the DSM-IV-TR, except for the factor school phobia, which is not recognized in this manual.

Various researchers in Spain have validated the SCARED in order to determine its functionality to measure the diverse symptoms of anxiety. Hale et al. (2013) found that, in a sample of 425 Spanish adolescents, the SCARED presented adequate psychometric properties with a stable reliability (between .75-.41). Domènech-Llaberia and Martínez (2008) also found adequate reliability for this instrument (Cronbach's global alpha of .83; for the factors from .44 to .72; and test-retest reliability of .72). There is also a version of the SCARED in the Catalan language (Vigil-Colet et al., 2009); this instrument was applied to 1490 students of primary education. In this study, Cronbach's alpha had a value of .86, and four factors were found instead of five in the factor analysis: Panic/somatic (α = .78), Social phobia (α = .69), Generalized anxiety (α = .69) and Separation anxiety (α = .70). Regarding school refusal, Romero et al. (2010) performed a study on the comorbidity of the anxiety factors of the SCARED and depressive symptomatology in children from 8 to 12 years, also finding that the factor school phobia was the least comorbid and least prevalent. These results coincide with prior investigations showing that this factor presents lower psychometric properties than the other four (Birmaher et al., 1999; Domènech-Llaberia & Martínez, 2008; Muris, Schmidt, & Engelbrecht, 2002; Vigil-Colet et al., 2009), associating this result with the small number of items, only 4, to assess this factor on the SCARED. Nevertheless, faced with this controversy, Hale, Crocetti, Raaijmakers, and Meus (2011), in a cross-cultural meta-analysis, found that in spite of the fact that the school refusal factor had weaker psychometric properties than the rest, it was considered an independent dimension of SAD, and the five-factor structure was subsequently corroborated in the investigation carried out by Hale et al. (2011).

- •

“Inventario de Ansiedad Escolar” (School Anxiety Inventory; SAI; García-Fernández, Inglés, Martínez-Monteagudo, Marzo, & Estévez, 2011). The IAES assesses school anxiety situations and responses in students between 12 and 18 years through four situational factors and three factors referring to the three response systems of anxiety (cognitive, psychophysiological, and motor) that students may present in different school settings. The IAES is made up of 23 items and is rated on a 5-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). It is completed by students according to the frequency of each response, with higher scores indicating more anxiety. The IAES assesses four factors: (a) Anxiety due to Failure and School Punishment (AFSP), (b) Social Appraisal Anxiety (SAA), (c) Aggression Anxiety (AA), and (d) School Evaluation Anxiety (SEA). The response systems include three factors: (a) Cognitive Anxiety (CA), (b) Behavioral Anxiety (BA), and (c) Psychophysiological Anxiety (PA).

García-Fernández et al. (2011) analyzed the psychometric properties of the IAES scores from a study carried out with 520 Spanish students of compulsory secondary education (CSE) and high school. The structure of four situational factors and the three factors of the anxiety response systems was supported by the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, which accounted for 74.97% of the total variance, and for the factors of the response systems: 68.64% of cognitive anxiety, 58.51% of motor anxiety, and 67.70% of psychophysiological anxiety. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) of the SAI scores were: .93 (SAA), .92 (AFSP and AA), .88 (SEA), .86 (CA and PA), and .82 (BA). Test-retest reliability with a 2-week interval was: .84 (AFSP and SEA), .83 (SAA), .78 (AA), .77 (CA), .75 (PA), and .74 (BA). Currently, there are various versions of the IAES in other countries such as Slovenia (Puklek, Inglés, Marzo, & García-Fernández, in press) and Chile (Lagos-San Martín, García-Fernández, Inglés, Gómez-Núñez, & Martínez-Monteagudo, in press).

This instrument has been used in other national investigations to analyze the relationships and predictive capacity between school anxiety and trait anxiety, state anxiety and depression (Martínez-Monteagudo, García-Fernández, & Inglés, 2013), as well as the relation between school anxiety and academic achievement (García-Fernández, Martínez-Monteagudo, & Inglés, 2013). The IAES has also been used to identify different profiles of students with school anxiety and possible significant differences between the profiles found and psychoeducational variables such as social climate and school violence (Martínez-Monteagudo, Inglés, Trianes, & García-Fernández, 2011).

After these findings, the authors García-Fernández et al. (2014) examined the SAI to reduce the number of items and validate a short version of this instrument. As a result, the short version of the SAI (SAI-S) contains 15 items about school situations and 15 items referring to the three systems of the anxiety response. In spite of this modification in the number of items, the 5-point Likert-type response format is maintained and the target population is still 12 to 18 years. Analysis of internal consistency provided satisfactory scores between .77 and .94, and the test-retest reliability coefficients ranged from .74 to .87, and this work obtained similar results to those reported by García-Fernández et al. (2011). Lastly, Inglés, García-Fernández, Marzo, Martínez-Monteagudo, and Estévez (in press) found configural and measurement invariance for all the dimensions of the IAES by sex and age groups in another sample of Spanish adolescents.

Kearney and Bates (2005) recommend using a multi-method assessment in investigations focused on anxiety and school refusal. Therefore, the application of various assessment instruments should be promoted, not only in children or adolescents, but, also in their relatives. In the school setting, it is important to know the influence and perception of the teachers (Gastaldi, Pasta, Longobardi, Prino, & Quaglia, 2014; Rodríguez et al., 2014), a personal factor that can also provide relevant information for the diagnosis.

Treatment of school refusal in SpainThe complexity of school refusal behavior also involves the intervention area, because it is a problem that is difficult to overcome if exclusively viewed from the perspective of the affected student. Hence, it is necessary for various personal agents of the educational community (students, parents, teachers, and internal or external specialists) to participate.

Most of the national works found are case studies that attend to children and adolescents with school phobia or group intervention programs to prevent absenteeism. With regard to the case studies, most research is based on cognitive behavioral therapy, incorporating two essential strategies: systematic desensitization or gradual exposure to the school setting and contingency management (Bragado, 2006; Coronado, 2000; Espada & Méndez, 2002; Méndez & Maciá, 1998). Among the techniques employed in these interventions are in vivo exposure, social skills training, the therapeutic contract, contingency management, and coping skills. The initial interview is carried out with the student who refuses to go to school and the family, and self-reports, such as the “Inventario de Miedos Escolares” (IME [School Fears Inventory] Méndez, 1988), are administered to obtain more precise information of the case and the factors maintaining the behavior. Nevertheless, no specific measure is applied that evaluates school refusal to identify the cause or causes that justify this maladaptive behavior.

Regarding intervention programs, their approach focuses mainly on samples of adolescents at risk of presenting absentee behaviors. Faced with this problem, various autonomous communities of Spain have implemented programs for prevention, detection and/or intervention in order to regularize schooling and prevent school absenteeism from leading to negative consequences (Aguado, 2005; Bueno, 2005; Castro & Barreiro, 2013; Gargallo & Garfella, 2000). Most of these studies raise absenteeism as an educational and social problem, pointing to measures set within the legal framework and establishing the sociological profile developed by the absentee child and his or her risk factors. In spite of a variety of goals with regard to the objectives, duration, development, and results, all the proposals present common features sharing the same aim, to achieve schooling for all students in the shortest time possible (Miñaca & Hervás, 2013).

Future lines of research of school refusal in SpainThroughout the present national review, it has been shown that research of school refusal in Spain is a field of study which should be extended (González-González, 2006). In spite of being a problem in the school centers, the theoretical and experimental references that justify and analyze its relevance are scarce.

Firstly, we need to establish and strengthen a conceptual limitation about the different theoretical currents underpinning the behavior of school refusal. The distinction between absenteeism and school phobia established in Spain must be overcome in order to investigate all the students who refuse to go to school. Accordingly, we note the proposal of Kearney (2008) as one of the strongest international tendencies. According to this approach, school refusal behavior includes any type of absence from school based a functional model of four factors that justify such behavior: (a) avoiding the negative affect provoked by stimuli or situations related to the school setting, (b) escaping from evaluation situations or social aversion, (c) seeking the attention of significant others and (d) seeking tangible reinforcements outside of the school setting.

To perform experimental studies on this topic, we need to have an instrument that specifically measures school refusal. In Spain, there are only instruments that assess this behavior as a subscale within other categories, for example, SAD, by means of instruments like the SCARED, the IAES, or the ADIS-IV interview. Nevertheless, for future research, we propose the validation of instruments that allow the specific assessment of this phenomenon, and the most frequently used scale internationally is the SRAS-R (Haight et al., 2011). This instrument should have versions aimed both at children and at parents and teachers; it should also be applied in the different educational stages. National research has focused on the stages of primary education, and, especially, CSE. We therefore propose the validation of the SRAS-R in Spanish sample, both in primary education and in CSE, and to design a pioneer assessment instrument, both nationally and internationally, which could determine the cause or causes underlying the behavior of school refusal in children between 3 and 5 years. Such interest is justified by the fact that, during the stage of early childhood education, the first experiences of school refusal behavior are suffered, leading to a negative mental prototype towards school that can prevail during the child's entire schooling. Intervention will not be adequate unless the origin of the refusal is known.

Different studies have shown that the SRAS-R has adequate psychometric properties (Haight et al., 2011, Kearney, 2006a; Lyon, 2010). However, the analysis of its items by this research group led the reformulation of some of these items because they may be too complex for children from the 2nd cycle of primary education to understand. The idea is to avoid the use of items formulated as questions that, at the same time, establish a comparison with the rest of their peers (e. g., “How often do you have more negative feelings—for example, scared, nervous, or sad—than other kids your age?” or “How often do you avoid other people at school, compared with other kids your age?”). It would also be suitable to design a new questionnaire to assess school refusal according to the functional model proposed by Kearney, but establishing differences in terms of item formulation. Their drafting should not generate response ambiguity and should be similar to the current reality in which the students are developing. Once the instrument to identify subjects with this problem has been designed and validated, we propose expanding the analysis of comorbidity between school refusal behavior and other disorders related to separation, social, or generalized anxiety, depression, and behavior disorders in order to obtain possible support for the findings of international research on the subject (Burton, Marshal & Chisolm, 2014; Hochadel, Frölich, Wiater, Lehmkuhl, & Fricke-Oerkermann, 2014; Ingul & Nordahl, 2013).

Parallel to the study of assessment, we need to establish a treatment or intervention program adapted to the needs of each case. No national intervention programs that take into account the causal heterogeneity of school refusal have been found. Most of the investigations have focused on programs aimed at absentee behavior and applied at the stage of CSE (Aguado, 2005; Bueno, 2005; Castro & Barreiro, 2013). In this sense, the existence of absentee behaviors may be the consequence of prior school refusal during the primary education stage. Therefore, we propose as a future line of work the design and application of specific programs targeting the primary education stage in order to alleviate possible behaviors of school refusal, either already present or that may arise over time. The progressive development of the behavior of school refusal is well known, and it can culminate in undesired school failure, truancy, or, still worse, in dropping out of the educational institution (Kearney, 2007). From the reviewed national investigations, it is clear that risk factors for school refusal are not only personal variables related to the absentee subject, but also the influence of the family environment, the educational institution, and the peer group. In view of these results, an intervention proposed for a case of school refusal should be of a multidimensional nature and should take into consideration the various areas that influence this behavior.

Lastly, Spain is a country that in the past decades has seen its school population from other cultural identities increase exponentially (Díaz-Reales, 2010; Llorent, 2013). Recent studies have examined the integration of students from other countries or ethnic groups to analyze the degree of educational inclusion and its impact on academic performance and relations with the peer group. Hernández, Rodríguez and Moral (2011), after analyzing the integration of Gypsy students using sociometric types, found that the family environment was the main risk factor for school maladjustment. In turn, school maladjustment may be a risk factor leading to behaviors of school refusal. Therefore, not having found scientific antecedents assessing school refusal behavior in Spanish minority samples, either ethnic groups, population of foreign origin, or socially disadvantaged population, we need to determine the indices of school refusal presented by these students, the reason for their refusal to attend school, and to propose courses of action to resolve their difficulties, fears, or lack of interest in school.

International research of school refusalInternational contextualization and transcendenceEducation is one of the most influential factors in the advancement and progress of society. Its consideration as a pillar for people's development has been present in most societies. However, it is particularly relevant in today's world, which requires constant learning and versatility to changes. Given its importance in human development, there are many investigations focusing on the behavior of school refusal.

Countries like the United States (USA), the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia lead the research on school refusal (Kearney, 2008). In the case of the USA, within its educational decalogue, in which the ten major problems related to American education are listed, is school truancy (Zhang, Katsiyannis, Barrett, & Willson, 2007). This interest is justified by the rates of students who do not exercise their right and obligation to attend school and, consequently, are at risk for adverse consequences linked to this problem: anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior, low academic performance, or dropout (Kearney, 2008). Various national centers created in this country deal exclusively with the assessment of educational aspects, such as, for example, the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) and the National Center for School Engagement (NCSE). The existence of a national center that expresses in statistics the topics related to the educational setting is very interesting, as it allows knowing, among other things, the rates of school refusal and their evolution over time. The NCES (2006) indicated that 19% of the 4th graders and 20% of the 8th graders—corresponding to 4th grade of primary education and 2nd grade of CSE, respectively, in the Spanish system—had missed 3 days of classes during the past month. On the other hand, 7% of the 4th graders had 5 missed days in the past month. These findings highlight the prevalence of this phenomenon, for which proposals like that of the NCSE, 2006bNCSE (2006) are made, indicating that it is not enough to make students go to school, but instead that resources are needed to promote their desire to go to school. Currently, interest in research on this topic has expanded borders with investigations in European countries (Knollmann, Reissner, Kiessling, & Hebebrand, 2013; Lenzen et al., 2013), Japan (Nishida, Sugiyama, Aoki, & Kuroda, 2004; Terada et al., 2012), or Turkey (Bahali, Tahiroglu, Avci, & Seydaoglu, 2011). In Europe, we highlight the Working in Europe to Stop Truancy Among Youth (WE-STAY) project developed to collect epidemiological information on school truancy in European adolescents and to propose effective intervention models. Among the collaborating countries is Spain, which forms part of this initiative to prevent absenteeism in adolescents.

From the findings, it is clear that school refusal behavior is an international problem that concerns society, and in view of which, measures to detect, prevent, and intervene in it have been adapted.

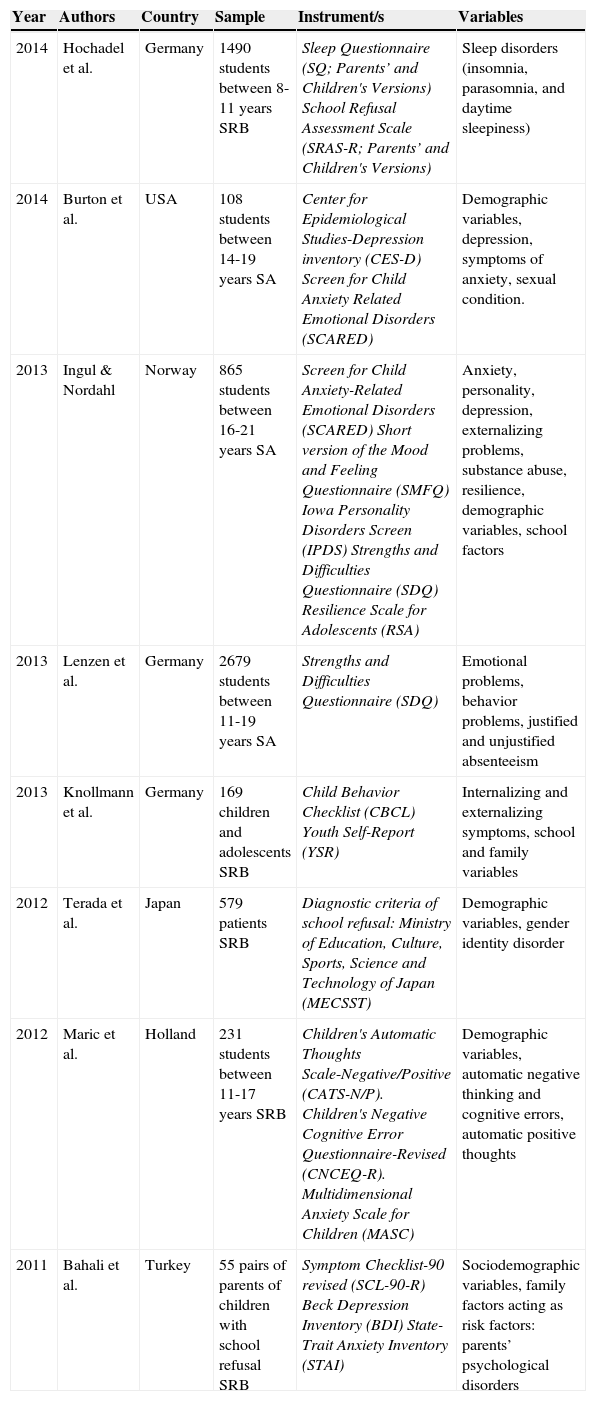

Risk factors and other variables related to school refusal at the international levelTable 1 summarizes the main studies carried out internationally on the risk factors and other variables related to school refusal behavior during the past 4 years. In general, it is possible to identify among the main factors studied in connection with school refusal: (1) sociodemographic variables, (2) anxiety, (3) depression (4) academic factors, and (5) family factors.

International studies of the risk factors and variables related to school refusal (2011-2014).

| Year | Authors | Country | Sample | Instrument/s | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Hochadel et al. | Germany | 1490 students between 8-11 years SRB | Sleep Questionnaire (SQ; Parents’ and Children's Versions) School Refusal Assessment Scale (SRAS-R; Parents’ and Children's Versions) | Sleep disorders (insomnia, parasomnia, and daytime sleepiness) |

| 2014 | Burton et al. | USA | 108 students between 14-19 years SA | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression inventory (CES-D) Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) | Demographic variables, depression, symptoms of anxiety, sexual condition. |

| 2013 | Ingul & Nordahl | Norway | 865 students between 16-21 years SA | Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) Short version of the Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (SMFQ) Iowa Personality Disorders Screen (IPDS) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Resilience Scale for Adolescents (RSA) | Anxiety, personality, depression, externalizing problems, substance abuse, resilience, demographic variables, school factors |

| 2013 | Lenzen et al. | Germany | 2679 students between 11-19 years SA | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Emotional problems, behavior problems, justified and unjustified absenteeism |

| 2013 | Knollmann et al. | Germany | 169 children and adolescents SRB | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Youth Self-Report (YSR) | Internalizing and externalizing symptoms, school and family variables |

| 2012 | Terada et al. | Japan | 579 patients SRB | Diagnostic criteria of school refusal: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MECSST) | Demographic variables, gender identity disorder |

| 2012 | Maric et al. | Holland | 231 students between 11-17 years SRB | Children's Automatic Thoughts Scale-Negative/Positive (CATS-N/P). Children's Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire-Revised (CNCEQ-R). Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) | Demographic variables, automatic negative thinking and cognitive errors, automatic positive thoughts |

| 2011 | Bahali et al. | Turkey | 55 pairs of parents of children with school refusal SRB | Symptom Checklist-90 revised (SCL-90-R) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | Sociodemographic variables, family factors acting as risk factors: parents’ psychological disorders |

Note: SA: school absenteeism; SRB: school refusal behavior.

Regarding the sociodemographic variables, most research indicates a prevalence rate of school refusal of about 5% (Sewell, 2008), in spite of the fact that it can reach 28 and 35% due to the causal heterogeneity that can include the behavior of school refusal considered as an inclusive construct (Mihalas, 2014). Moments that involve a change for the student, for example, the start of the academic course, changing to a new school, or the transition to another educational stage, are considered periods of peak incidence of this phenomenon (Pina, Zerr, Gonzales, & Ortiz, 2009). Kearney and Beasley (1994) performed a study on the prevalence of school refusal between 5 and 17 years as a function of the age of youths with school refusal. Their results showed the highest rate of school refusal occurred between 7 and 9 years, representing 31.5%, whereas the lowest rates were between 5 and 6 years (11.2%) and between 16 and 17 years (15.2%). As a function of the variable sex, school refusal is equally distributed in boys and girls, as reported in some investigations (Fremont, 2003; Guare & Cooper, 2003). Likewise, Maric, Heyne, and de Heus (2012), in their study with a sample of 231 adolescents between 11 and 17 years, found no significant sex differences, whereas the older participants had a greater probability of suffering from school refusal. Subsequent studies have found that dropout levels are higher for boys (9.1%) than for girls (7%) (Kearney & Spear, 2014). With regard to the socioeconomic level and racial origin, Kearney and Bates (2005) found that the prevalence was fairly balanced, without important distinctions among the participants.

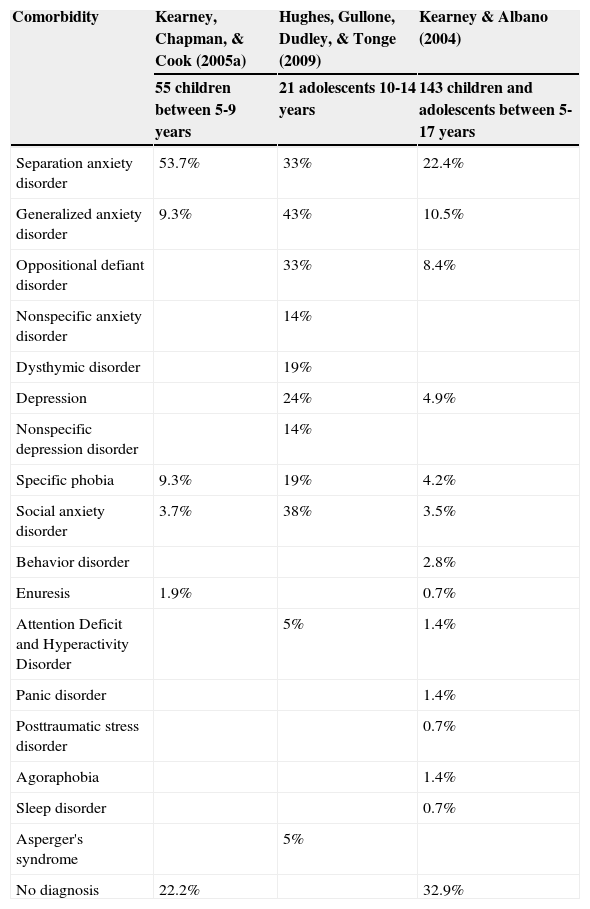

Regarding comorbidity of school refusal behavior with other psychological disorders, we note the findings associating this phenomenon with anxiety disorders (Brandibas, Jeunier, Clanet, & Fouraste, 2004) (see Table 2). From the review carried out, the comorbidity of school refusal with SAD, GAD, social anxiety disorder, ODD, and specific phobia is predominant in child and adolescent sample.

Comorbidity of school refusal.

| Comorbidity | Kearney, Chapman, & Cook (2005a) | Hughes, Gullone, Dudley, & Tonge (2009) | Kearney & Albano (2004) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 55 children between 5-9 years | 21 adolescents 10-14 years | 143 children and adolescents between 5-17 years | |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 53.7% | 33% | 22.4% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 9.3% | 43% | 10.5% |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 33% | 8.4% | |

| Nonspecific anxiety disorder | 14% | ||

| Dysthymic disorder | 19% | ||

| Depression | 24% | 4.9% | |

| Nonspecific depression disorder | 14% | ||

| Specific phobia | 9.3% | 19% | 4.2% |

| Social anxiety disorder | 3.7% | 38% | 3.5% |

| Behavior disorder | 2.8% | ||

| Enuresis | 1.9% | 0.7% | |

| Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder | 5% | 1.4% | |

| Panic disorder | 1.4% | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.7% | ||

| Agoraphobia | 1.4% | ||

| Sleep disorder | 0.7% | ||

| Asperger's syndrome | 5% | ||

| No diagnosis | 22.2% | 32.9% |

On the other hand, there are studies in which multilevel analysis was applied to analyze school truancy, although not school refusal globally. In this field, we found works examining absenteeism in many different schools (Ervasti et al., 2012; Nygren, Bergstrom, Janlert, & Nygren, 2014) as well as comparative studies of 14-year-olds in order to detect general patterns in the casuistry and consequences of truancy at the individual, school, and country levels (Claes, Hooghe, & Reeskens, 2009).

Assessment of school refusal at the international levelThere are diverse methods to assess school refusal behavior and they involve the participation of the affected students as well as their parents and teachers. Among the assessment proposals identified from theoretical and empirical research, we note three systems to make a proper diagnosis: the interview, assessment of this behavior from a functional approach using the SRAS-R; and the application of self-reports that appraise variables related to school refusal (Kearney & Albano, 2007a). Before using interviews and questionnaires, a medical examination should be performed to determine the child's health status in order to rule out any type of illness that presents the somatic symptoms associated with school refusal (stomach aches, headaches, nausea, vomiting, etc.).

The interviewThe interview is a technique used prior to the diagnosis in which are analyzed, based on the interviewees’ responses, aspects of the family structure, academic performance, frequency of school refusal behavior, prior situations and consequences of this behavior observed over time, and other relevant issues that help to understand the origin of the behavior of school refusal and to plan the intervention. Like at the national level, the ADIS-IV-C interview for children and parents is used predominantly. Therefore, this instrument is one of the most firmly entrenched as a semi-structured interview for the assessment of the school refusal (Hughes et al., 2009; Kearney, Pursell, & Álvarez, 2001).

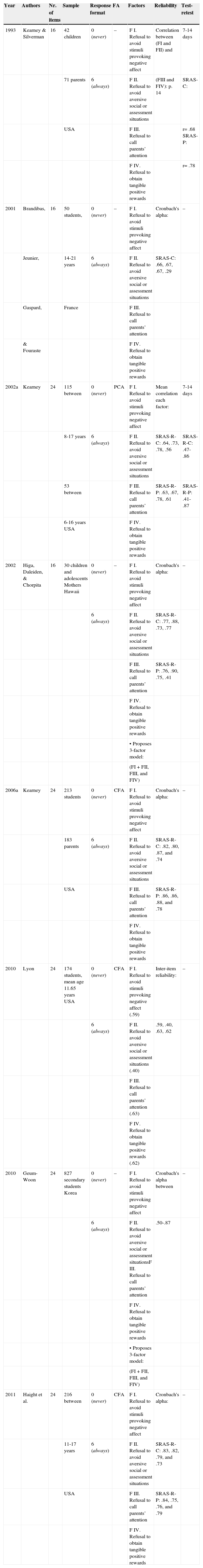

Specific measures to assess school refusal: SRAS-RAmong the procedures to assess school refusal behavior, we underline the SRAS-R (Kearney, 2002a). This test is designed to identify the self-perception of the four main factors explaining the causes underlying school refusal: (a) avoiding stimuli or situations related to the school setting, (b) escaping from aversive social or evaluative situations, (c) seeking caregivers’ attention, and (d) obtaining tangible positive reinforcement outside of the school.

This instrument is a revision of the initial proposal of the SRAS-C (Kearney & Silverman, 1993) to which were added 8 items with regard to the original 16-item instrument, and some existing items were modified to adapt them to changes in the conception of the functional model. The revised version is made up of 24 items with a 7-point response scale (0 = never, 6 = always) and is aimed at children and adolescents between 8 and 17 years, in addition to the version targeting parents.

Both the original and the revised scale have shown satisfactory psychometric properties and adequate validity and reliability indices for the 4-factor model (Haight et al., 2011; Kearney, 2002a; Kearney & Silverman, 1993; Lyon, 2010). -Table 3 presents the results obtained to date in the validations that have been carried out with the SRAS-R. Other instruments such as the FSA scale, developed by Watanabe and Koishi (2000) to assess feelings associated with school refusal from three factors (bad feelings about the school, no friends, and aversion to going to school); the SAS, proposed by Fujigaki (1996) to assess school refusal with two factors (aversion to the school and avoidance of the school); and the SRPE, an instrument based on prior studies by Honjo (1987, 1990) to assess personality tendencies in children and youth with school refusal, are the only ones found at a worldwide level that assess school refusal specifically. However, more research on their use and application to different populations is needed to increase the amount of consistent assessment protocols allowing the comparison of the results (Kearney, 2003).

Validations of the SRAS-R.

| Year | Authors | Nr. of items | Sample | Response format | FA | Factors | Reliability | Test-retest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Kearney & Silverman | 16 | 42 children | 0 (never) | – | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Correlation between (FI and FII) and | 7-14 days |

| 71 parents | 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | (FIII and FIV): p. 14 | SRAS-C: | ||||

| USA | F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | r= .68 SRAS-P: | ||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | r= .78 | |||||||

| 2001 | Brandibas, | 16 | 50 students, | 0 (never) | – | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Cronbach's alpha: | – |

| Jeunier, | 14-21 years | 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | SRAS-C: .66, .67, .67, .29 | ||||

| Gaspard, | France | F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | ||||||

| & Fouraste | F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | |||||||

| 2002a | Kearney | 24 | 115 between | 0 (never) | PCA | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Mean correlation each factor: | 7-14 days |

| 8-17 years | 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | SRAS-R-C: .64, .73, .78, .56 | SRAS-R-C: .47-.86 | ||||

| 53 between | F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | SRAS-R-P: .63, .67, .78, .61 | SRAS-R-P: .41-.87 | |||||

| 6-16 years USA | F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | |||||||

| 2002 | Higa, Daleiden, & Chorpita | 16 | 30 children and adolescents Mothers Hawaii | 0 (never) | – | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Cronbach's alpha: | – |

| 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | SRAS-R-C: .77, .88, .73, .77 | ||||||

| F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | SRAS-R-P: .76, .90, .75, .41 | |||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | ||||||||

| • Proposes 3-factor model: | ||||||||

| (FI + FII, FIII, and FIV) | ||||||||

| 2006a | Kearney | 24 | 213 students | 0 (never) | CFA | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Cronbach's alpha: | – |

| 183 parents | 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | SRAS-R-C: .82, .80, .87, and .74 | |||||

| USA | F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | SRAS-R-P: .86, .86, .88, and .78 | ||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | ||||||||

| 2010 | Lyon | 24 | 174 students, mean age 11.65 years USA | 0 (never) | CFA | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect (.59) | Inter-item reliability: | – |

| 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations (.40) | .59, .40, .63, .62 | ||||||

| F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention (.63) | ||||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards (.62) | ||||||||

| 2010 | Geum-Woon | 24 | 827 secondary students Korea | 0 (never) | – | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Cronbach's alpha between | – |

| 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situationsF III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | .50-.87 | ||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | ||||||||

| • Proposes 3-factor model: | ||||||||

| (FI + FII, FIII, and FIV) | ||||||||

| 2011 | Haight et al. | 24 | 216 between | 0 (never) | CFA | F I. Refusal to avoid stimuli provoking negative affect | Cronbach's alpha: | – |

| 11-17 years | 6 (always) | F II. Refusal to avoid aversive social or assessment situations | SRAS-R-C: .83, .82, .79, and .73 | |||||

| USA | F III. Refusal to call parents’ attention | SRAS-R-P: .84, .75, .76, and .79 | ||||||

| F IV. Refusal to obtain tangible positive rewards | ||||||||

Note: CFA: confirmatory factor analysis; FA: Factor analysis; PCA: principal component analysis; –: data not found.

The behavior of school refusal is linked to other disorders grounded in anxiety, phobias, or depression. Thus, among the self-report measures used in research to assess such factors are included: the Negative Affect Self-Statement Questionnaire (NASSQ; Ronan, Kendall, & Rowe, 1994) focused on the assessment of anxiety and depression; the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978) which assesses general, situational, and psychophysiological anxiety; the Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (SASC-R; La Greca & Stone, 1993) based on social anxiety; the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997), which measures physical, social, and separation anxiety; the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992), based on the evaluation of depression; the Fear Survey Schedule for Children-Revised (FSSC-R; Ollendick, 1983), focused on the assessment of general fears; the Daily Life Stressors Scale (DLSS; Kearney, Drabman, & Beasley, 1993), which measures a child's anxiousness in daily situations; and the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991), designed to assess behavior problems. Not all these instruments have a Spanish version (e.g., the NASSQ and the DLSS). In contrast, diverse national studies have applied the rest of these instruments, for example, the -RCMAS (Chorot, Valiente, & Sandín, 2002), the SASC-R (Chorot et al., 2002; Sandín, 1999; Sandín, Chorot, Valiente, Santed, & Sánchez-Arribas, 1999), the MASC (Domingo, García-Villamisar, & Vidal, 2002), the CDI (Del Barrio, Roa, Olmedo, & Colodrón, 2002; Ezpeleta, 1990; Figueras, Amador-Campos, Gómez-Benito, & Del Barrio, 2010; Romero et al., 2010; Viñas, Jané, & Domènech-Llaberia, 2000), the FSSC-R (Chorot et al., 2002; Sandín, 1997; Sandín & Chorot, 1998; Valiente, Sandín, Chorot, & Tabar, 2003), and the YSR (Figueras et al., 2010; Lacalle, Domènech-Massons, Granero, & Ezpeleta, 2014; Lemos et al., 1992, Lemos, Fidalgo, Calvo, & Menéndez, 1992, 1994; Lemos, Vallejo, & Sandoval, 2002Lemos et al., 2002; Sandoval, Lemos, & Vallejo, 2006). These instruments complement the measures identified at the national level because they do not assess school refusal as a subscale, but instead focus on disorders that are comorbid with school refusal.

Measures targeting parents and teachers also provide relevant information about the behavior of the student suffering from school refusal. Among the instruments aimed at this population, we note the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986) aimed at parents, and the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Edelbrock & Achenbach, 1984) for teachers. National studies were found that apply all these instruments, such as the CBCL together with the CDI (Ezpeleta, 1990), the YSR (Lacalle et al., 2014), the FES adapted to Spanish (Cantón & Cortés, 2000) and published by TEA editions in 1987; or the “Cuestionario de Aceptación-Rechazo Parental” [Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire] and the “Cuestionario de Evaluación de Personalidad” [Personality Assessment Questionnaire; Gracia, Lila, & Musitu, 2005). Studies aimed at teachers using the TRF (De Paúl & Arruabarrena, 1995) were also found.

Treatment of school refusal at the international levelThe success of an intervention in school refusal behavior implies the design of a multimodal treatment adapted to the individual characteristics of the child or adolescent and to the external agents, like the family, the social and the school environment (Oner, Yurtbasi, Er, & Basoglu, 2014). This principle is shared worldwide and its application is defended to perform an adequate intervention.

Diverse studies have verified the relation between this problem and anxious or depressive manifestations, and one of the most widely used and effective techniques is cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT; Heyne, Sauter, Van Widenfelt, Vermeiren, & Westenberg, 2011; Maric, Heyne, Mackinnon, Van Widenfelt, & Westernberg, 2013).

CBT uses diverse strategies to modify irrational thoughts (e.g., systematic desensitization, use of emotive imagination, etc.). However, not all the children and youth who refuse school justify their absenteeism due to anxiety or phobia, so the students who refuse to attend school because they find positive external reinforcers for their behavior would be excluded.

Faced with such a heterogeneous population (Carroll, 2010), international research emphasizes the importance of designing interventions on the basis of the cause or causes of school refusal. For this purpose, a prescriptive model of intervention is proposed, according to which, depending on the causes identified by means of the SRAS-R, a series of strategies to overcome this difficulty are suggested (Kearney, 2007). According to this model, subjects with school refusal can justify their behavior through one or more factors, applying a series of strategies depending on the cause of their behavior.

For children who refuse school to avoid negative stimuli associated with the school or to escape from the aversion of social and/or assessment situations, the intervention techniques imply psychoeducation, exercises to control somatic symptoms, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and techniques of progressive exposure to the school.

In the case of children with school refusal who are seeking significant others’ attention, the treatment implies the establishment of educational routines and patterns in the family setting as well as contingency control.

Regarding the fourth factor, and therefore, children and / or youth who skip school to obtain “tangible rewards out of school”, the intervention consists of contingency contracts, and in these cases, the implementation of follow-up and control of class attendance is necessary.

In order to demonstrate the validity of this type of treatment, Kearney and Silverman (1999) carried out a comparative intervention between two approaches, one based on the prescriptive model and one that is not. The results in anxiety, depression and time out of school obtained by the subjects who received a non-prescriptive intervention were worse than the results of the students who received the prescriptive model. In a similar vein, subsequent treatment guidelines aimed at parents and specialists strengthen therapy strategies based on a prescriptive treatment, therefore, attending to the causes of this behavior (Kearney & Albano, 2007a; Kearney & Albano, 2007b).

On the other hand, Kearney and Graczyk (2014) performed a theoretical review of the intervention measures carried out in prior empirical investigations. These authors distinguish three levels of school refusal behavior as a function of the degree of absenteeism, and note the need for the schools to know the prevalence of their students’ absenteeism. They propose the routine use of functional assessment to determine the main causes of school refusal and consequently, to design interventions better adapted to the educational reality.

From a technological approach, Gutiérrez-Maldonado, Magallón, Rus, and Peñaloza (2009) proposed a type of intervention based on virtual reality, applying their proposal to 36 children between 10 and 15 years. This type of technique considerably increases children's motivation to participate in the treatment and guarantees, in turn, their comprehension, flexibility, and cooperation by means of the design of virtual environments that they must face (access to the school, the classroom, the playground, etc.).

Regarding pharmacological intervention, no studies underlining the use of these means to deal with school refusal were found. Nevertheless, we did find some mention of pharmacological methods in the theoretical reviews, in order to combat strong symptoms of anxiety or depression (Kearney, 2006b, 2008), in spite of the fact that most empirical experiences apply cognitive behavioral strategies and do not use medication.

Future international lines of research of school refusalThe international documental review reveals the advances carried out in other countries with regard to school refusal behavior. Nevertheless, on the basis of the identified limitations, new challenges are proposed in this field of knowledge that will help to reduce the prevalence of this problem.

There are international assessment scales that evaluate the behavior of this phenomenon specifically. However, only the SRAS-R is consolidated as the main assessment instrument due to the number of validations that have verified its reliability and validity in different parts of the world, such as the USA (Haight et al., 2011; Higa et al., 2002; Kearney, 2002a; Kearney & Silverman, 1993; Lyon, 2010), Korea (-Geum-Woon, 2010), and France (Brandibas et al., 2001). Longitudinal studies analyzing the variations over time in school refusal behavior are needed in the current research (Kearney, 2008), as no prior studies have been found. However, there are some follow-up works assessing related behaviors or disorders, such as truancy (Attwood & Croll, 2015; Dembo et al., 2013) or different anxiety disorders (GAD, SAD, panic disorder, school anxiety, and social anxiety disorder; Nelemans et al., 2014), but no investigations focused specifically on the longitudinal assessment of school refusal were found.

Therefore, we need to strengthen the instruments already created or promote the design of new measures to assess the behavior of school refusal specifically. Throughout this study, we have underlined the importance of the fact that the study and treatment of school refusal should take into consideration the different parties involved: children, parents, and teachers. Many works were found assessing school refusal behavior in children taking into consideration the child and parents’ perception (Kearney, 2006a, Kearney, 2007; Kearney & Albano, 2004).However, no studies were found that apply the SRAS version for teachers. Kearney and Silverman (1993) indicate in their work the existence of a version aimed at teachers. Nevertheless, subsequent investigations only mention the availability of versions targeting children and parents (Kearney, 2006c). Therefore, we need to design and validate a scale aimed at teachers that will allow us to determine their perception of the behavior of school refusal.

Regarding the educational level included in most of these studies, they consider the primary and secondary education stages, like those found at the national level. In view of the need to investigate at lower levels, Kearney et al. (2005a) carried out a research with 55 children with school refusal aged between 5 and 9 years, proposing some recommendations for their assessment and treatment. In this sense, it is necessary to expand the number of investigations, both nationally and internationally, that assess school refusal in subjects who are initiating their schooling or experiencing the transition between early childhood education and primary education, educational moments at which the rates of incidence of this phenomenon rise (Pina et al., 2009).

Regarding the intervention systems analyzed, most research focuses on case studies that attend to subjects who present school refusal behavior (Hendron & Kearney, 2011; Kearney, 2002b; Kearney, Chapman, & Cook, 2005b; Moffitt, Chorpita, & Fernández, 2003). This type of intervention is considered appropriate, as it deals with individual differences present in the subject. Nevertheless, in view of the relevance of identifying this problem in its early stages, we propose increasing the number of intervention programs applied at the group level to prevent school refusal. Lyon (2010) refers to the construct of school refusal ideation. This term refers to a student's disposition to present the behavior of school refusal, so it is proposed that future works should examine longitudinally the usefulness of the SRAS-R to predict school refusal by setting cut-points for its prevention.

On the other hand, we note the proposal of Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al. (2009) who suggest using new means of support, in this case computers, to treat school refusal. The use of technological tools for the assessment or treatment of school refusal behavior is a field of research with few precedents, so scientific contributions in this area could be precursors of new instruments and application methods, as well as in the field of intervention, through virtual environments or other strategies.

To conclude, we note the diverse international theoretical studies that provide a review of the current state of research on school refusal behavior (Kearney, 2003, 2008; Kearney & Bensaheb, 2006; Walitza, Melfsen, Della-Casa, & Scheneller, 2013), as well as those of Spanish origin from bibliometric reviews (Gonzálvez, Inglés, Gomis-Selva, -Lagos-San Martín, & Vicent, 2014). However, the aim of this work was to expand the recompilation of the main advances in this area of knowledge and to provide, in turn, a comparison between the Spanish state and the rest of the international investigations, proposing new lines of research on the basis of the identified limitations. We hope the challenges posed serve as a stimulus for researchers interested in the study of school refusal behavior.

This work has been financed by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Ref: EDU2012-35124) and FEDER, awarded to Prof. Dr. José Manuel García Fernández.