This paper analyzes the effect of conditional mediation of environment-competitive strategy in business orientation of family businesses. In order to study the results we propose a method based on a second generation structural equation (PLS-SEM) where software SmartPLS 3.2.6 is applied to measure data of 174 Spanish family businesses. This paper presents a relevant contribution both to the academic field and the performance of family firms, helping to understand the process of transforming international entrepreneurial orientation into a better international performance through competitive strategy while family businesses invest their efforts in aligning international entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy with international results, bearing in mind the positive moderator effect of environment.

Este trabajo analiza el efecto de mediación condicionada entorno-estrategia competitiva en la orientación empresarial de las empresas familiares. Para el análisis de los resultados se propone la utilización de un método de ecuaciones estructurales de segunda generación (PLS-SEM) donde el software SmartPLS 3.2.6 es aplicado a los datos de 174 empresas familiares españolas. Este trabajo presenta una contribución relevante tanto para el ámbito académico como para la práctica de las empresas familiares, ayudando a entender cómo se produce realmente el proceso de conversión de la orientación emprendedora internacional en un mejor desempeño internacional a través de la estrategia competitiva, que permite que las empresas familiares ajusten sus esfuerzos en alinear la orientación emprendedora internacional y la estrategia competitiva con los resultados internacionales, teniendo presente el efecto moderador positivo del entorno.

Over the last years, entrepreneurial orientation, internationalization, competitive strategies and environment have been of academic and business interest. This paper intends to answer these questions and how they interact. The first two concepts are linked by the so-called international entrepreneurial orientation which is a new field of research focused on the observation of innovative, risky and proactive behaviors of international companies (Kropp, Lindsay, & Shoham, 2006). There are two ways to contextualize international entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Miller, 2014): operate it using traditional scales in an international context or determine it as a subset of entrepreneurial orientation. This paper chooses the first conceptualization analyzing international entrepreneurial orientation as a similar concept than entrepreneurial orientation, being international environment the subject of study. This scope has been developed following the Miller (1983), Covin and Slevin (1989) scale.

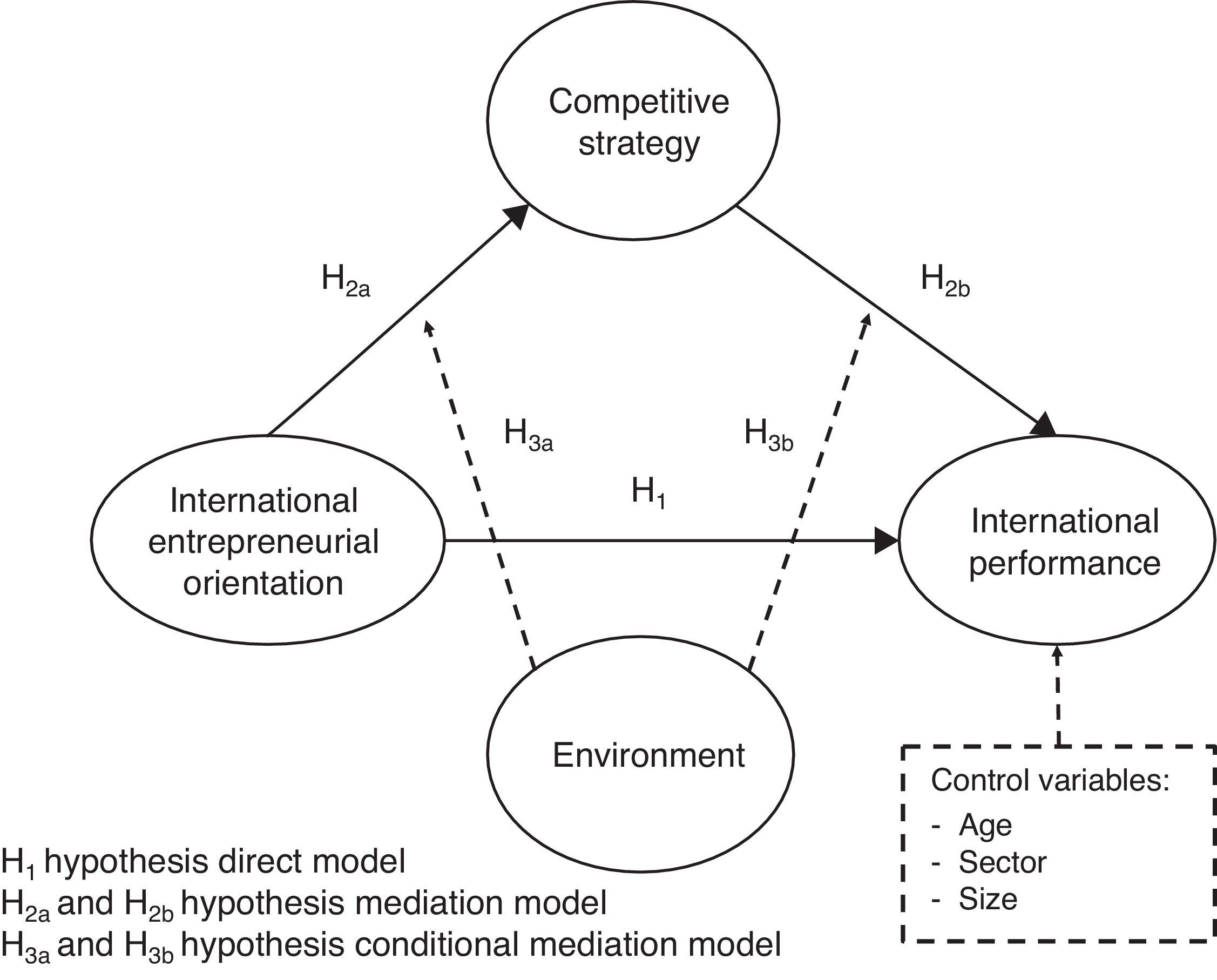

Most papers show the influence of international entrepreneurial orientation in general business activity. Many companies tend to extend their trade beyond their imaginary boarders in order to maintain or improve the level of competitiveness (Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida, 2000; Sapienza, Autio, George, & Zahra, 2006) and cut down their reliance to domestic and national markets (Ciravegna, Majano, & Zhan, 2014). One of the significant inputs of this paper is the role international entrepreneurial orientation plays in relation to international performance of companies according to a multi-item scale which includes frequency of international activity, satisfaction received from it and outcomes of internationalization (Balabanis & Katsikea, 2004; Dimitratos, Lioukas, & Carter, 2004; Etchebarne, Geldres, & García-Cruz, 2010). The aim of this approach is to shed light on the explanation power of entrepreneurial orientation from a different and dynamic perspective in order to analyze the process of internationalization (Hernández-Perlines, Moreno-García, & Yañez-Araque, 2016). With everything, we pose the following research question: Does the international entrepreneurial orientation influence the international performance of family businesses?

Competitive strategy is the third element tackled in this paper. Competitive strategy clearly affects the performance of the company and creates competitive advantage (Porter, 1980). Competitive strategy of companies can be weighted from diverse approaches (i.e. Chrisman, Hofer, & Boulton, 1988; Miles, Snow, Meyer, & Coleman, 1978), although Porter's model is the most accepted. This paper stands that competitive strategy sets a balance between international entrepreneurial orientation and international performance as similar conceptions do believing in the existence of such mediation between entrepreneurial orientation and general performance of companies (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2016; Moreno & Casillas, 2008). In short, the second research question: does competitive strategy mediate the influence of international entrepreneurial orientation on the international performance of family firms?

The fourth element considered in this paper is environment. It plays a remarkable role in the development of international entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Slevin, 1991; Kreiser, Marino, Dickson, & Weaver, 2010; Zahra, Neubaum, & Huse, 1997). Among published papers, there are some outlining studies analyzing the moderator effect of environment on entrepreneurial orientation of companies which put into practice strategies of internationalization (Balabanis & Katsikea, 2004; Miller, 1983; Russell & Russell, 1992; Tan, 1996). Therefore, the third research question that we raise in this paper is: Does the environment moderate the mediating effect of competitive strategy on the influence of international entrepreneurial orientation on the international performance of family firms?

Here we try to answer the research call posted on Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, and Frese (2009), Wales, Monsen, and McKelvie (2011) and Covin and Miller (2014) to keep on studying entrepreneurial orientation and its relation to internal variables (competitive strategy) and external variables (business environment). With such scientific goal, the variables considered (international entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy) have been measured from a business point of view (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011).

Companies selected to be object of study in this paper are family businesses located in Spain. This election is justified by the fact that these companies represent a significant part of the productive fabric – as in many other countries. Family businesses represent 88.8% of the total of working companies in Spain, 57.1% of gross value added and 66.7% of private employment (Corona & Del Sol, 2016). Therefore, we cannot deny that these types of companies are an important force of growth and wellbeing (Astrachan & Shanker, 2003; Sirmon, Arregle, Hitt, & Webb, 2008).

In order to quantify results and verify theories, we propose a structural equation modeling based on PLS-SEM and SmartPLS 3.2.6 software (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015). Data have been gathered from an emailed questionnaire sent to CEOs of family businesses associated to the Institute of Family Businesses of Spain. Once the process was completed – carried out from November 2014 to February 2015 – data from 174 family businesses was recorded.

Following this introduction, the structure of this paper consists of a review of the most important literature on international entrepreneurial orientation, competitive strategy and business environment as well as the theories to be verified. The third part of the paper introduces our research design with a reference to the targeted population and methods of measurement of variables. The fourth part compares given theories to structural equation with the assistance of software SmartPLS 3.2.6 (Ringle et al., 2015) and analyzes the results obtained. The study closes with the most relevant conclusions deducted from research and the exposition of future research lines.

Theory and hypothesisInternational entrepreneurial orientationDespite research on business internationalization has increased reasonably in the last years, there is a remaining challenge to answer questions merging as a result of the increase of a globalized and competitive environment where companies have to operate (Werner, 2002).

Previous studies prove the existence of a positive connection between entrepreneurial orientation and outcomes (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Covin & Slevin, 1989; Miller, 1983; Wiklund, 1999; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003; Zahra, 1991; Zahra & Covin, 1995) for which entrepreneurial orientation is a valuable indicator of business success (Krauss, Frese, Friedrich, & Unger, 2005).

Literature on business organization offers different approaches to internationalization.1 Nonetheless, entrepreneurism is gaining importance in the past years given its profound explanatory capacity about the process of creating value for companies which work beyond their original borders (Joardar & Wu, 2011; Jones & Coviello, 2005; Weerawardena, Mort, Liesch, & Knight, 2007). This is how international entrepreneurial orientation was born as an unusual and dynamic way to explain the will of companies to go international (i.e. Freeman & Cavusgil, 2007; Sundqvist, Kyläheiko, Kuivalainen, & Cadogan, 2012).

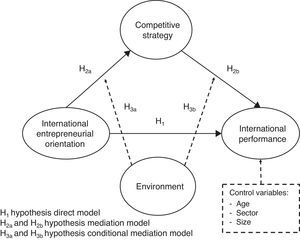

In this sense, many authors have studied the influence of entrepreneurial orientation on international development of companies. Most of them support that the first influences the second positively (i.e. Balabanis & Katsikea, 2004; Dimitratos et al., 2004; Etchebarne et al., 2010; Godwin Ahimbisibwe & Abaho, 2013). This drives us to our first hypothesis:H1 International entrepreneurial orientation has a positive influence on international development of family businesses.

Many experts not only analyze the influence of international entrepreneurial orientation on results but also the facts that affect the relation between variables such as the effect of market and industry (Lohrke, Franklin, & Kothari, 2015), technology (Knight, 2000), domestic factors (Balabanis & Katsikea, 2004), business capacities (Godwin Ahimbisibwe & Abaho, 2013).

Literature about business introduces a variety of categories to classify competitive strategy: Porter's typology (1980) which sets the difference between cost leadership and differentiation (i.e. Dess, Lumpkin, & Covin, 1997), and Baum, Locke, and Smith (2001) who uses taxonomy to observe the relation between entrepreneurial orientation and performance. On the other hand, Miles et al.’s proposal (1978) separates four strategic patterns: (1) prospective strategy, (2) defensive strategy, (3) analyzing strategy, (4) reactive strategy (patterns used by Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) to detect the role of entrepreneurial orientation in its relation to business performance. Porter's typology has been selected for this paper due to its huge popularity in literature (Allen & Helms, 2006; Chaganti, Cook, & Smeltz, 2002). Competitive strategy has been taken as the combination of differentiation and cost leadership thanks to its contribution to create synergies for companies, what leads to better results (Abdullah, Mohamed, Othman, & Uli, 2009; Campbell-Hunt, 2000; Murray, 2001; Parnell, 2010).

Apart from these factors, some other writers have focus on the influence of business strategy on the connection between entrezpreneurial orientation and business performance. Some authors take it as a moderator influence (i.e. Dess et al., 1997) and some others as mediator (i.e. Borch, Huse, & Senneseth, 1999). We have considered the second approach for this paper. This is: competitive strategy intervenes between entrepreneurial orientation and international business performance. This mediator effect of competitive strategy has been object of study for experts such as Naidu and Prasad (1994) or Bell, Crick, and Young (2004). Considering this, we can state the following hypothesis:H2 Competitive strategy affects the influence of international entrepreneurial orientation on international performance of family businesses.

Mediator model leads to the conception of two relations. On the one hand, international entrepreneurial orientation affects competitive strategy positively. On the other hand, competitive strategy has a positive influence on international performance. Entrepreneurial orientation, thanks to its innovative dimension, has an effect on competitive strategy through technology entrepreneurism and new valuable products for costumers. Therefore, there is a noticeable association between innovation and product differentiation (Blumentritt & Danis, 2006). In addition, innovation improves the reduction of costs (Dowling & McGee, 1994). Proactive companies do not usually commit mistakes but they cut down expenses (Bidhé, 2000). Eventually, risk assumption helps to risk control and reduces costs and initial investment (Rauch et al., 2009). Which drives us to the following hypothesis:H2a International entrepreneurial orientation affects competitive strategy of family businesses positively.

Many empirical papers show positive connections between competitive strategy and results according to Porter's conception (i.e. Allen & Helms, 2006; Leask & Parker, 2007; Phelan, Ferreira, & Salvador, 2002). Other approaches analyze the positive effect of competitive strategy in relation to international performance (Brush, Edelman, & Manolova, 2015; Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Onetti, Zucchella, Jones, & McDougall-Covin, 2012), which leads us to the next hypothesis:H2b Competitive strategy has a positive influence on international performance of family businesses.

Environment plays an important role when it comes to international entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Slevin, 1991; Kreiser et al., 2010; Zahra et al., 1997). Environment analysis may be tackled from two different perspectives:

- 1)

Dimension composition: Mintzberg (1973) was the first author to study and name the various dimensions of environment including dynamism, complexity, hostility and diversity.

- 2)

Institutional approach: analysis of regulative, normative and cognitive elements (Scott, 1995).

This paper focuses on the first perspective. Among these four dimensions, hostility and dynamism have been the most studied (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2004; Covin & Slevin, 1989, 1991; Zahra, 1991, 1993). From the literature it is clear that the environment moderates positively the entrepreneurial orientation. Miller (1983) states that the environment and its dimensions have a positive moderating effect on the entrepreneurial orientation. Companies that adapt to dynamic environments take better advantage of opportunities presented to them (Covin & Slevin, 1989). Russell and Russell (1992) argue that dynamic and hostile environments favor the achievement of higher levels of performance. On the other hand, Wood and Robertson (1997) and Francis and Collins-Dodd (2000) affirm that the influence of the entrepreneurial orientation in the performance of the companies will be greater in dynamic and unstable environments. On the other hand, Lohrke et al. (2015) indicate that the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance is moderated by market and industry factors. Also, Zahra and Garvis (2000) highlight the positive moderating effect of hostile environments on the influence of entrepreneurial orientation on corporate performance. Dimitratos et al. (2004) argue that environmental conditions have a positive moderating effect on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance. Kuivalainen, Puumalainen, Sintonen, and Kyläheiko (2010) affirm that the competitiveness of the environment reinforces the influence of the entrepreneurial orientation on the entrepreneurial performance. For Casillas and Moreno (2010) the dynamism of the environment has a significant moderating impact on the entrepreneurial orientation. Finally, Cruz and Nordqvist (2012) the competitive environment is strongly correlated with the entrepreneurial orientation. For other authors, environmental turbulence is a moderating factor that reinforces the effect of competitive strategies on company performance (Souza, Bayus, & Wagner, 2004). On the other hand, the perception of environmental uncertainty affects changes in competitive strategy (Hult, Snow, & Kandemir, 2003; Pelham & Wilson, 1995; Zahra & Covin, 1995). The following moderator hypothesis exposed is a result of the previous:H3 Environment moderates the mediation of competitive strategy on international entrepreneurial orientation of family businesses.

The previous moderator hypothesis may be divided into two subhypothesis:H3a Environment moderates the relation between international entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy in family businesses. Environment moderates the relation between competitive strategy and the performance of family businesses.

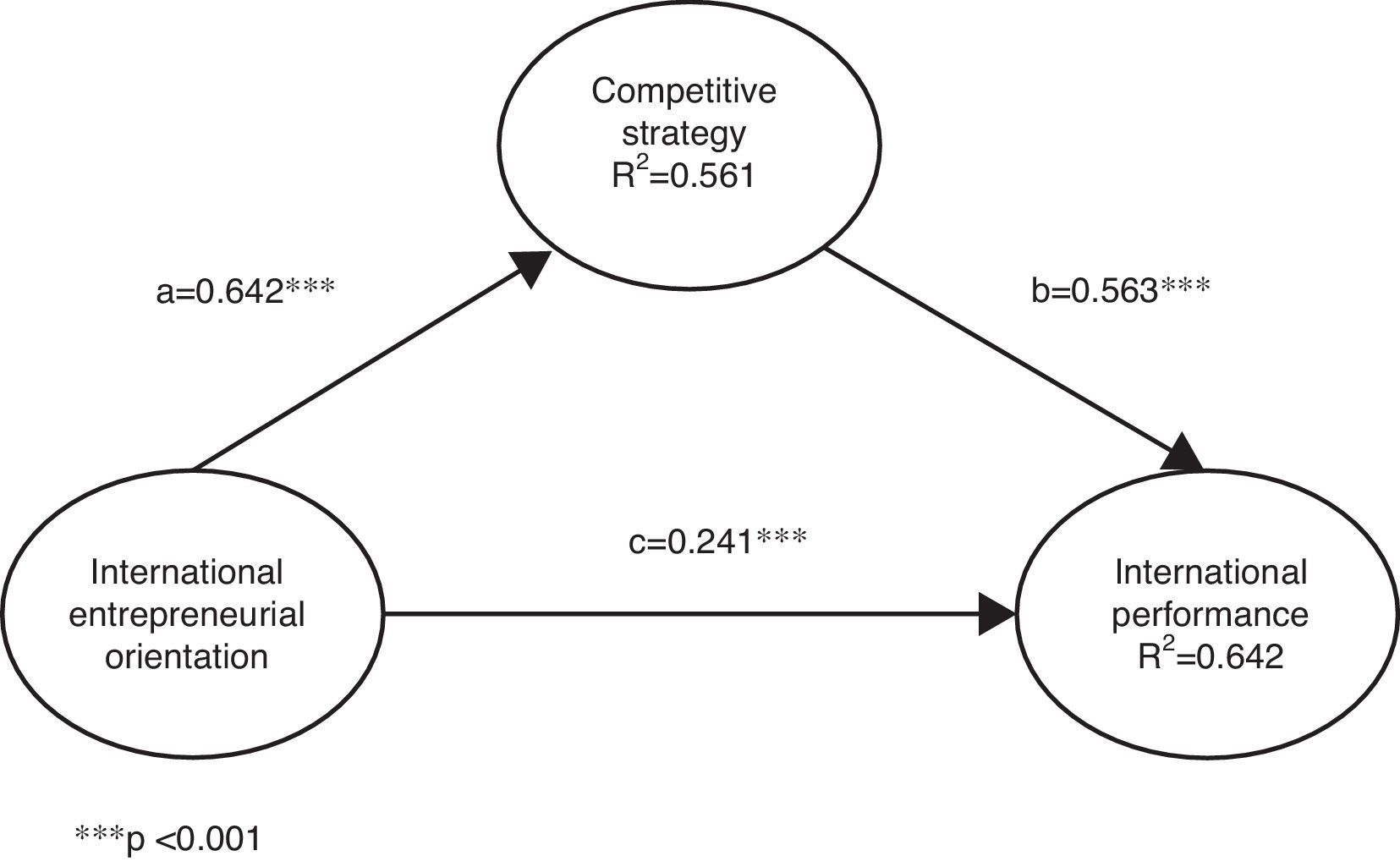

Once the literature review has been carried out and the corresponding hypotheses have been presented, the conceptual model is shown in Fig. 1.

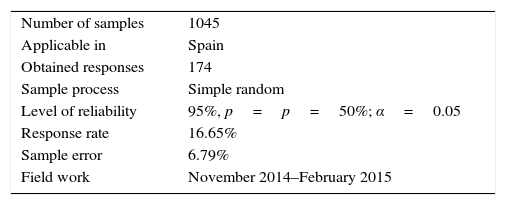

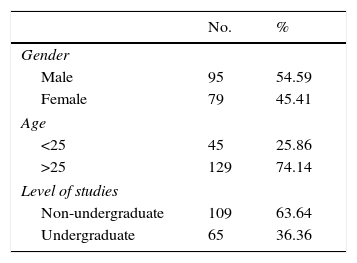

MethodologyDataData of international entrepreneurial orientation and international performance were gathered from a questionnaire sent via email through Limesurvey v.2.5 to the highest executive position of a group of companies taken from the Institute of Family Businesses of Spain. The questionnaire contained Likert-style questions (1–5). After finishing field work done between November 2014 and February 2015, we obtained 174 valid responses (Table 1).

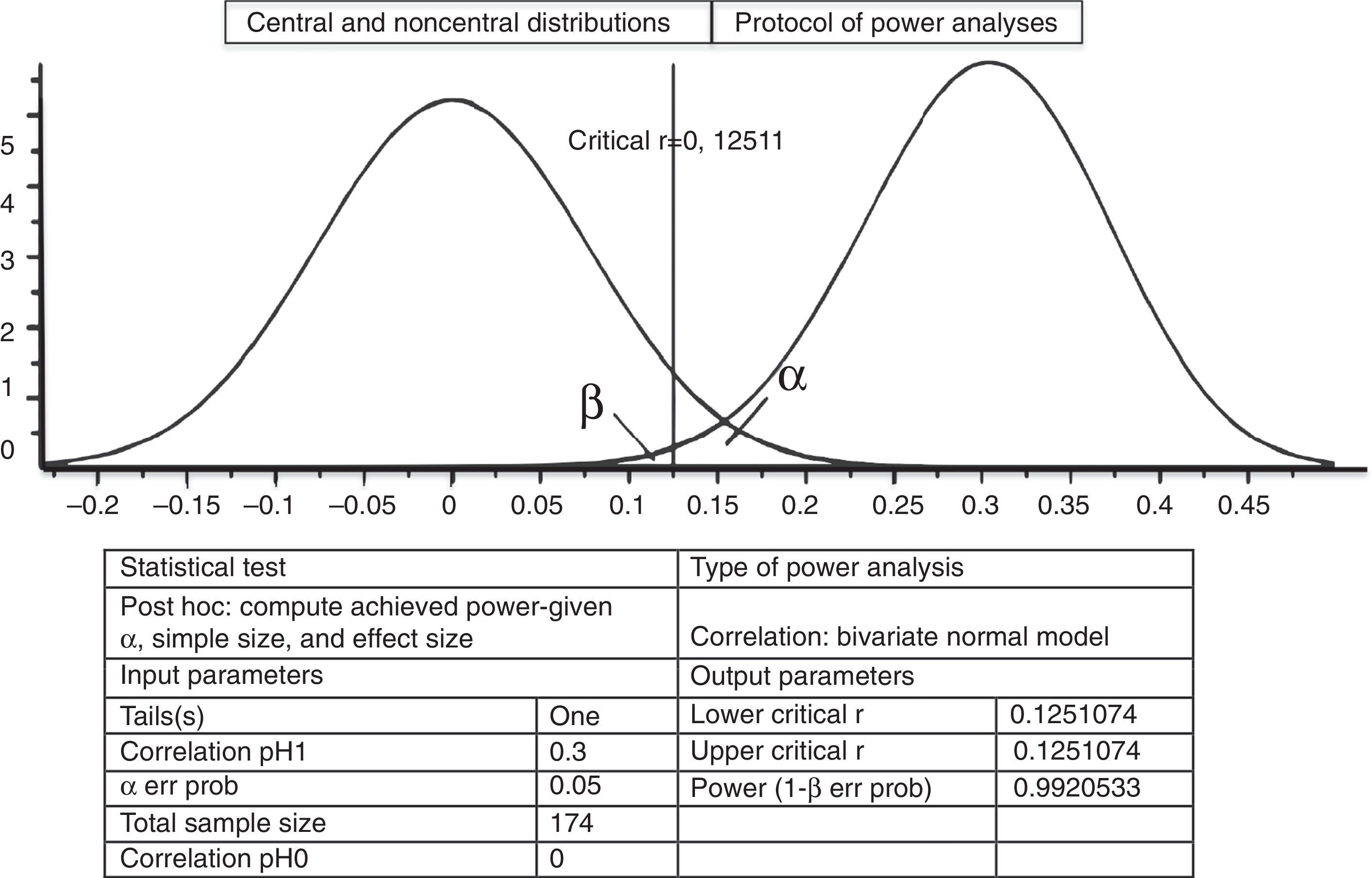

Up to this point, we need to calculate whether the number of samples is accurate to apply multiple regression analysis of the SEM-PLS model. According to Barclay, Higgins, and Thompson (1995) the minimum number of samples to apply heuristic regression results from multiplying x 10 the number of indicators of the higher formation indicator scales. For us, international entrepreneurial orientation is a second-order type b formed by three variables which are defined by three dimensions, what makes a total of 9 indicators. This makes 90 the minimum number of samples to apply SEM-PLS. We got 174, overpassing the limit.

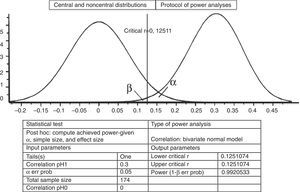

We can also carry out a study of statistical power of the sample using Cohen's retrospective test (1992) and software G* Power 3.1.9.2 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009). Sample of target family businesses is very powerful statistically: 0.934 (higher than 0.80 limit established by Cohen, 1992) (Fig. 2).

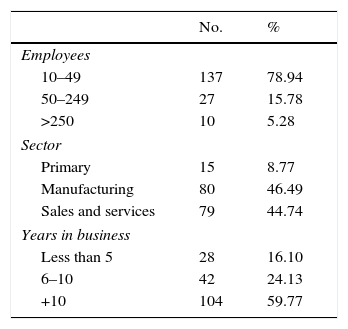

The most relevant characteristics of the companies in the sample are those shown in Tables 2 and 3 shows the most outstanding characteristics of the interviewees.

When comparing theories and analysis of results, we have used the multivariable statistical technique of structural equation model Partial Least Square (PLS). This model is the most convenient to answer our research questions due to several reasons:

- 1)

Its predictable character (Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins, & Kuppelwieser, 2014, Sarstedt, Ringle, Smith, Reams, & Hair, 2014).

- 2)

It shows different causal relations (Astrachan, Patel, & Wanzenried, 2014; Jöreskog & Wold, 1982).

- 3)

It is less exigent with the small sample size (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015).

SmartPLS v.3.2.6 (Ringle et al., 2015) software was used for data analysis through SEM-PLS.

Measurement of variablesIndependent variable: International Entrepreneurial Orientation – This variable has been measured using the scale proposed by Miller (1983) and amended by Covin and Slevin (1989) and Covin and Miller (2014). They consider that international entrepreneurial orientation can be calculated from three dimensions: innovation (3 items), proactivity (3 items) and risk assumption (3 items). These variables have been made operative according to Likert scale (1.5).

Dependent variable: International performance – International performance is measured by a multi-items scale which includes export intensity – considered an international performance measure by Zahra et al. (1997) and Morgan (2004) – as well as satisfaction resulting from export performance – another measure recognized by Cavusgil and Zou (1994), Balabanis and Katsikea (2004), Dimitratos et al. (2004) and Zahra et al. (1997). Both variables above mentioned have been calculated according to Likert scale (1–5). The third item we have introduced to measure international performance refers to export results, used by Zahra et al. (1997), Morgan (2004) and Ibeh (2003).

Mediating variable: Competitive strategy – Competitive strategy has been measured by Robinson and Pearce scale (1988) of 22 items which analyses low-cost strategy and marketing, innovation as well as services differentiation.

Moderating variable: Environment – Scales proposed by Robertson and Chetty (2000), Balabanis and Katsikea (2004), Dimitratos et al. (2004), Etchebarne et al. (2010) and Kuivalainen et al. (2010) have been used to measure hostility and dynamism of environment.

Control variables – For control variables, size (number of employees), age (number of years since establishment) and the main activity sector of the family business were used, appearing on a recurring basis in studies on family businesses (Chrisman, Chua, & Litz, 2004).

ResultsTwo different steps were scoped in order to read PLS-SEM model (Barclay et al., 1995): (1) an analysis of measuring model and (2) an analysis of structural model. This guarantees that measuring scales proposed are valid and reliable.

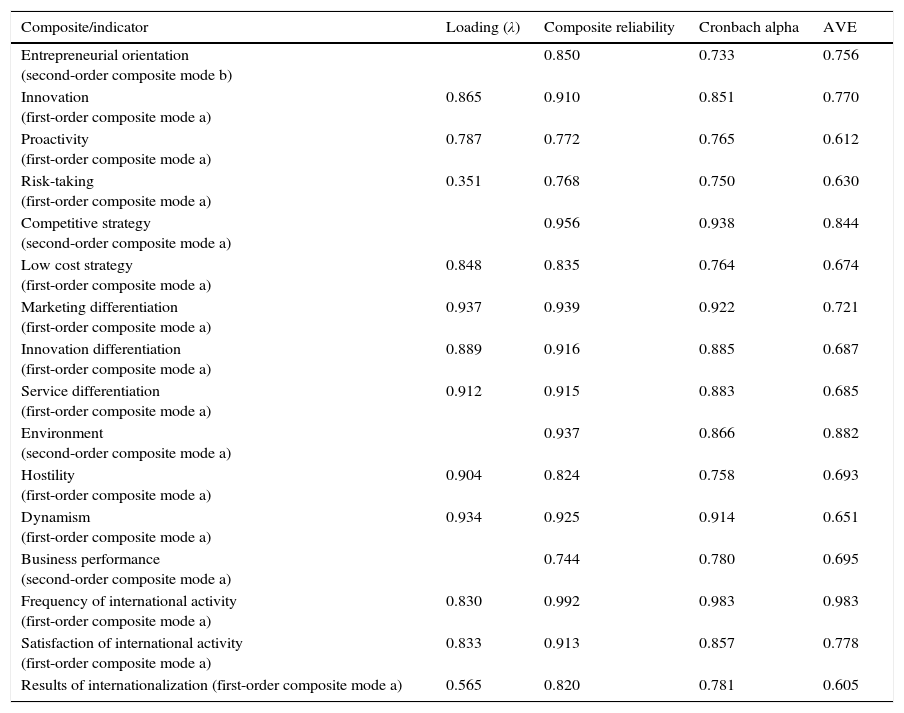

Evaluation of measuring modelFollowing Roldán and Sánchez-Franco recommendations (2012), our first step was to analyze values of Factor Loadings, Composite Reliability, Cronbach Alpha and Average Variance Extracted. Table 4 shows values of these indicators, which are superior to the limits set on literature2.

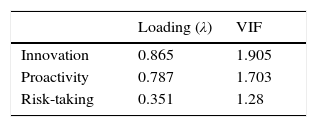

Factors and indicators.

| Composite/indicator | Loading (λ) | Composite reliability | Cronbach alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation (second-order composite mode b) | 0.850 | 0.733 | 0.756 | |

| Innovation (first-order composite mode a) | 0.865 | 0.910 | 0.851 | 0.770 |

| Proactivity (first-order composite mode a) | 0.787 | 0.772 | 0.765 | 0.612 |

| Risk-taking (first-order composite mode a) | 0.351 | 0.768 | 0.750 | 0.630 |

| Competitive strategy (second-order composite mode a) | 0.956 | 0.938 | 0.844 | |

| Low cost strategy (first-order composite mode a) | 0.848 | 0.835 | 0.764 | 0.674 |

| Marketing differentiation (first-order composite mode a) | 0.937 | 0.939 | 0.922 | 0.721 |

| Innovation differentiation (first-order composite mode a) | 0.889 | 0.916 | 0.885 | 0.687 |

| Service differentiation (first-order composite mode a) | 0.912 | 0.915 | 0.883 | 0.685 |

| Environment (second-order composite mode a) | 0.937 | 0.866 | 0.882 | |

| Hostility (first-order composite mode a) | 0.904 | 0.824 | 0.758 | 0.693 |

| Dynamism (first-order composite mode a) | 0.934 | 0.925 | 0.914 | 0.651 |

| Business performance (second-order composite mode a) | 0.744 | 0.780 | 0.695 | |

| Frequency of international activity (first-order composite mode a) | 0.830 | 0.992 | 0.983 | 0.983 |

| Satisfaction of international activity (first-order composite mode a) | 0.833 | 0.913 | 0.857 | 0.778 |

| Results of internationalization (first-order composite mode a) | 0.565 | 0.820 | 0.781 | 0.605 |

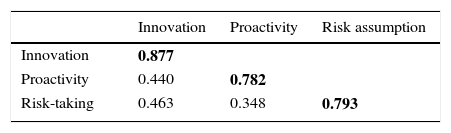

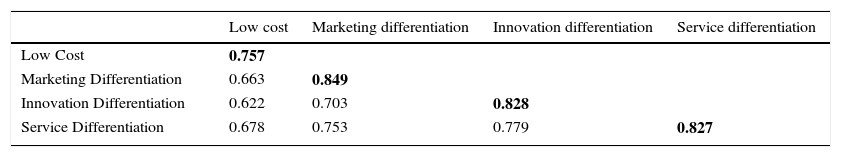

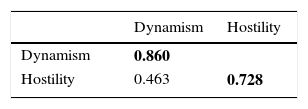

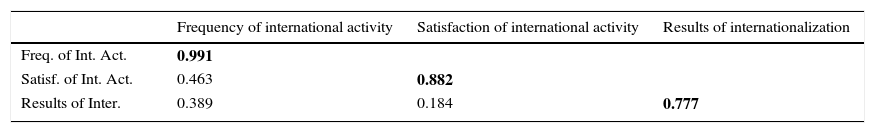

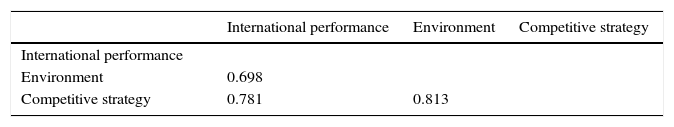

Discriminant validity was also calculated in order to observe to which extend a factor truly differs from others (Hair et al., 2014). To get such results, we compared AVE square root values of each factor vs. correlations between constructs associates to these factors (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All cases (see Tables 5–8) show values on the diagonal higher than corresponding correlations.

Discriminant validity of dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation.a

| Innovation | Proactivity | Risk assumption | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | 0.877 | ||

| Proactivity | 0.440 | 0.782 | |

| Risk-taking | 0.463 | 0.348 | 0.793 |

Discriminant validity of dimensions of competitive strategy.

| Low cost | Marketing differentiation | Innovation differentiation | Service differentiation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Cost | 0.757 | |||

| Marketing Differentiation | 0.663 | 0.849 | ||

| Innovation Differentiation | 0.622 | 0.703 | 0.828 | |

| Service Differentiation | 0.678 | 0.753 | 0.779 | 0.827 |

The bold values are Square root of the AVE.

Discriminant validity of dimensions of business performance.

| Frequency of international activity | Satisfaction of international activity | Results of internationalization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. of Int. Act. | 0.991 | ||

| Satisf. of Int. Act. | 0.463 | 0.882 | |

| Results of Inter. | 0.389 | 0.184 | 0.777 |

The bold values are Square root of the AVE.

In addition, we can calculate HTMT rate for Type A factors to measure discriminant validity between similar and different indicators. In order to fulfill discriminant validity, HTMT values must be lower than 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015). As shown in Table 9, all values are below 0.85.

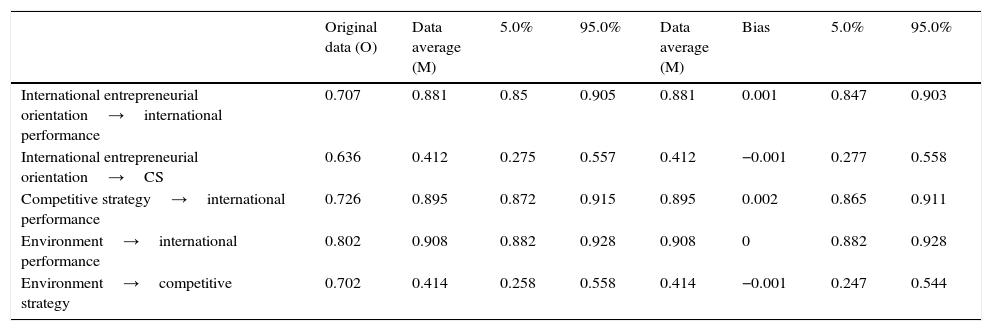

Eventually, we have calculated HTMTinference examining bootstrapping from 5000 sub samples. Where resultant interval is lower than 1, discriminant validity exists. Our case fulfills as so (see Table 10).

HTMTinference.

| Original data (O) | Data average (M) | 5.0% | 95.0% | Data average (M) | Bias | 5.0% | 95.0% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International entrepreneurial orientation→international performance | 0.707 | 0.881 | 0.85 | 0.905 | 0.881 | 0.001 | 0.847 | 0.903 |

| International entrepreneurial orientation→CS | 0.636 | 0.412 | 0.275 | 0.557 | 0.412 | −0.001 | 0.277 | 0.558 |

| Competitive strategy→international performance | 0.726 | 0.895 | 0.872 | 0.915 | 0.895 | 0.002 | 0.865 | 0.911 |

| Environment→international performance | 0.802 | 0.908 | 0.882 | 0.928 | 0.908 | 0 | 0.882 | 0.928 |

| Environment→competitive strategy | 0.702 | 0.414 | 0.258 | 0.558 | 0.414 | −0.001 | 0.247 | 0.544 |

All previous data show that indicators displayed to measure the different given factors is reliable and has discriminant validity.

International entrepreneurial orientation begun as a second-order composite mode b resulting from two phases of calculation of latent variables (Wright, Campbell, Thatcher, & Roberts, 2012). Diamantopoulos, Riefler, and Roth (2008) recommendations were taken into consideration in order to validate entrepreneurial orientation factor. Difficulties on collinearity may appear when Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) reaches or exceeds a value of 5 (Kleinbaum, Kupper, Muller, & Nizam, 1988). No contradictions on collinearity were found in our study (see Table 11).

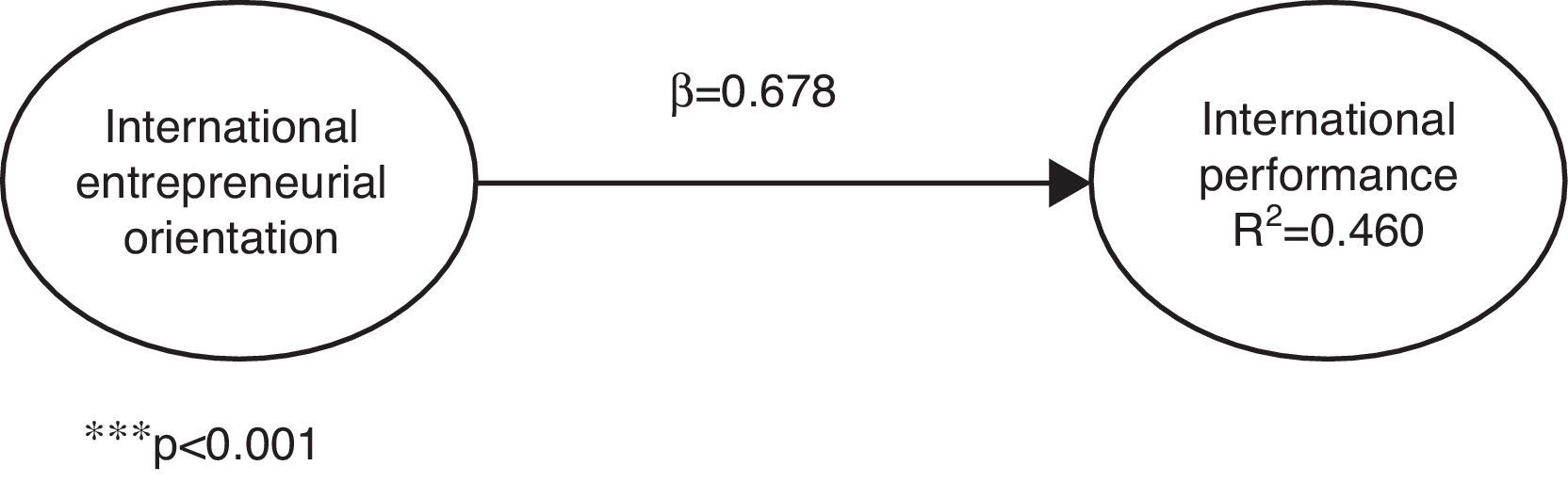

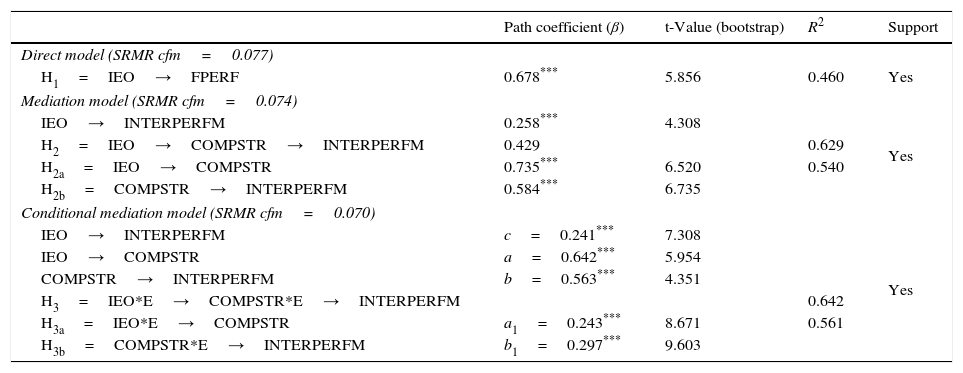

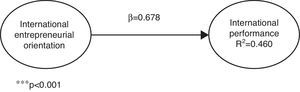

Analysis of structural modelFirst step consists on verifying direct relation between international entrepreneurial orientation (IEO) and international performance (INTERPERFORM). This is a positive and significant effect (β=0.678; p<0.001; Fig. 3).

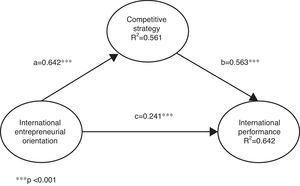

Second step introduces mediator variable effect (COMPSTR). It is remarkable that indirect effect is positive and significant (between IEO and COMPSTR T2: β=0.725; p<0.001, and between COMPSTR and INTERPERFRM T3: β=0.584; p<0.001; Fig. 4). Mediation effect does not eliminate direct effect completely given that the direct relation between international entrepreneurial orientation (IEO) and international performance (INTERPERFRM) gathers β=0.258; p<0.001. Mediation occurs (Baron & Kenny, 1986) although this is not full. How much does mediator variable influence? To measure the extent of indirect effect, VAF (Variance Accounted For) (Iacobucci, Grisaffe, Duhachek, & Marcati, 2003) denotes the magnitude of indirect effect in comparison to total effect (direct effect+indirect effect): VAF=(a1b1)/(a1b1+c′), resulting in a value of 0.6246 (62.46% greater than 20% and fewer than 80%), which confirms the existence of partial mediation (Hair et al., 2014).

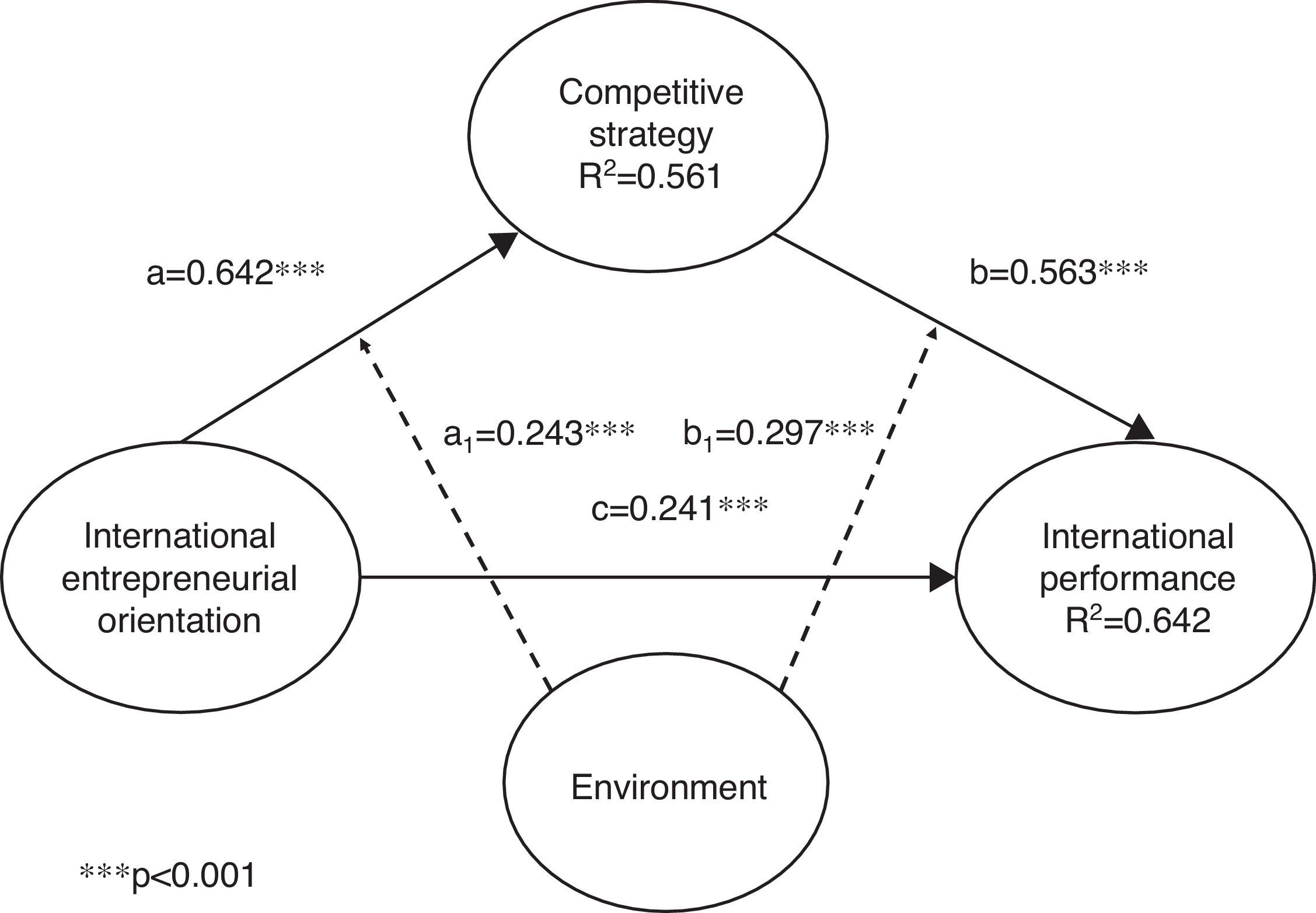

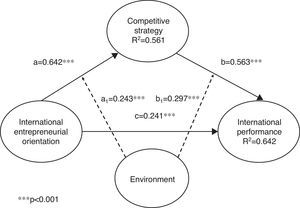

Third step consists on introducing moderator effect of environment when comparing international entrepreneurial orientation vs. competitive strategy (first moderator effect) as well as in the relation between competitive strategy and international performance (second moderator effect). As we can see, moderator effect of environment is present both in the relation IEO vs. competitive strategy (β=0.243; p<0.001) and competitive strategy vs. international performance (β=0.297; p<0.001). Moreover, this moderator effect increases explained variance of international performance almost in 2%, from 62.9% to 64.2%, confirming the double moderator effect of environment of the proposed model (see Fig. 5). Eventually, we observe that the magnitude of moderator effect of entrepreneurial orientation is average (Chin, 2010) with a value for the first moderator effect of environment f2=0.17 (environment moderates the relation between international entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy) and a result of 0.21 for the second moderator effect of environment (environment moderates the relation between competitive strategy and international performance).

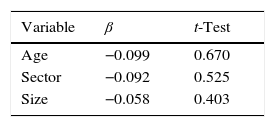

None of the control variables seen are relevant and significant (coefficients are inferior to 0.2 and t-test is less than recommended) (Table 12).

To complete the analysis of structural model, the model goodness-of-fit is tested by SRMR (standardized root mean square residual) proposed by Hu and Bentler (1998) and Henseler et al. (2015). In this case, SRMR value was 0.07 (less than the 0.08 recommended as accurate by Henseler et al., 2015). A summary of the results and of hypotheses can be seen in Table 13.

Structural model.

| Path coefficient (β) | t-Value (bootstrap) | R2 | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct model (SRMR cfm=0.077) | ||||

| H1=IEO→FPERF | 0.678*** | 5.856 | 0.460 | Yes |

| Mediation model (SRMR cfm=0.074) | ||||

| IEO→INTERPERFM | 0.258*** | 4.308 | Yes | |

| H2=IEO→COMPSTR→INTERPERFM | 0.429 | 0.629 | ||

| H2a=IEO→COMPSTR | 0.735*** | 6.520 | 0.540 | |

| H2b=COMPSTR→INTERPERFM | 0.584*** | 6.735 | ||

| Conditional mediation model (SRMR cfm=0.070) | ||||

| IEO→INTERPERFM | c=0.241*** | 7.308 | Yes | |

| IEO→COMPSTR | a=0.642*** | 5.954 | ||

| COMPSTR→INTERPERFM | b=0.563*** | 4.351 | ||

| H3=IEO*E→COMPSTR*E→INTERPERFM | 0.642 | |||

| H3a=IEO*E→COMPSTR | a1=0.243*** | 8.671 | 0.561 | |

| H3b=COMPSTR*E→INTERPERFM | b1=0.297*** | 9.603 | ||

First conclusion: international performance of family businesses can be mostly explained by international entrepreneurial orientation. This result coincides with previous researches (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2016; Miller & Friesen, 1983).

Second conclusion: competitive strategy has a moderator effect in the relation between international entrepreneurial orientation and international performance (Rauch et al., 2009). Such effect leads to an increase up to 62.9% of the capacity of this model to define explained variance of international performance.

Third conclusion: the environment moderates positively the mediation of competitive strategy on the influence of IEO in family business international performance. These outcomes are similar to previous studies (Moreno & Casillas, 2008).

This paper presents a relevant contribution both for the academic field and for the practice of companies, helping to understand how the process of converting the international entrepreneurial orientation to a better international performance through the competitive strategy. These will adjust their efforts to align the international entrepreneurial orientation and the competitive strategy with an improvement of the international results, bearing in mind the moderating effect of the environment. Managers of family firms with an international presence to improve their results should favor culture for innovation that is in line with the competitive strategy: a positive adjustment must be produced. But in addition, according to the international scope in which they operate, they should consider being pioneers or imitators and taking moderate risks that do not jeopardize the very survival of the family businesses.

This paper presents some limitations whose resolution may lead to future lines of research. First, the first limitation derives from the very conceptualization of the international entrepreneurial orientation composed of three dimensions: innovation, proactivity and risk taking (Covin and Miller, 2014; Miller, 1983). In this paper we have interpreted the entrepreneurial orientation as a second-order composite mode b (for more information see Covin & Wales, 2012; Hansen, Deitz, Tokman, Marino, & Weaver, 2011; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2016). However, some authors consider a different behavior of each of the dimensions of the entrepreneurial orientation (see Dai, Maksimov, Gilbert, & Fernhaber, 2014; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). As a future line of research, we propose to analyze the different effect of each dimension of the entrepreneurial orientation on the performance of family businesses. The second limitation stems from the joint consideration of the differentiation strategy and the cost leadership strategy. As a future line of research, independent consideration of each type of competitive strategy is proposed. The third limitation is a consequence of the global analysis of the dimensions of the environment. Possible lines of research would come from the particular study of each of the dimensions of the environment. The fourth limitation is the consideration of a multisectoral sample, which we select because we try to achieve a higher level of generalization of the results, but it might be interesting to analyze the effect of the international entrepreneurial orientation on international performance in a given sector. Finally, future longitudinal studies could be considered to see the effect of time in previous relationships and it would also be interesting to carry out studies of previous relationships between family firms originating in different countries.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest