This research paper aims at investigating the importance of work–family balance (WFB) on family businesses from Andalusia (Spain) and its impact on job satisfaction and employees’ commitment. The research objectives are twofold: (1) to classify companies based on the level of WFB implementation; (2) to investigate the differences between groups of companies in relation to job satisfaction, commitment, firm size and generation. In order to achieve these objectives an empirical study was conducted with a sample of 219 family businesses. The data collected using self-completion questionnaires were analyzed using cluster analysis and Manova. Main findings show a diffusion of WFB and broad implementation in this context. Thus, WFB has a positive impact on job satisfaction and on employees’ commitment. These findings contribute to the literature and practice highlighting the role of managers in the implementation of WFB and its subsequent positive return related to its impact on employees and society.

Esta investigación persigue estudiar la importancia de la conciliación entre trabajo y familia en las empresas familiares de Andalucía (España) y su influencia sobre la satisfacción laboral y el compromiso de los empleados. Los objetivos de investigación son: 1) clasificar las empresas en función del nivel de implementación de la conciliación entre trabajo y familia y 2) investigar las diferencias entre los grupos de empresas en relación con la satisfacción laboral, el compromiso, el tamaño de la empresa y la generación en la que se encuentran. Para conseguir estos objetivos, se ha llevado a cabo un estudio empírico con una muestra de 219 empresas familiares. Los datos han sido recogidos usando cuestionarios y se han analizado con análisis cluster y Manova. La principal conclusión es que la conciliación entre trabajo y familia está presente en buena parte de las empresas analizadas. Además, la Conciliación, tiene una influencia positiva sobre la satisfacción laboral y sobre el compromiso de los empleados. Estos hallazgos contribuyen al estudio académico de este fenómeno así como a la práctica empresarial, poniendo de manifiesto el papel de los directivos a la hora de implementar la conciliación y su consiguiente influencia positiva sobre los empleados y sobre la sociedad.

Companies are consistently exposed to highly pressurized environments in which their competing strategies can lead to broader job designs, high levels of stress, and inflexible conditions including long hours and the risk of a presenteeism mentality with hidden costs to organizations (Quazi, 2013). Some of these elements can be considered as the primary barriers in the integration between work and personal/family life. This is of major relevance in highly competitive environments but even more so in family businesses in which by the nature of their core activities they depend on their employees’ personal and professional commitment.

Employees are at the core of strategy implementation and without their professional commitment it is unlikely that companies will be able to improve their performance (Ruizalba, 2016). Instead of adopting a resource-based view approach in which employees are regarded resources or inputs to the organizational process, it is argued here that employees are much more than that. They are individuals with dignity and their personal and family circumstances that play an important role in their wellbeing and happiness. This subsequently affects company performance, whether managers recognize it or not.

In this sense, work is a relevant dimension of human life but it is not the main activity. Work also affects the worker as by working, women and men not only change the environment, but to some extent, also change themselves, either experiencing satisfaction or dissatisfaction or, in a more permanent form, acquiring or developing qualities that generate true human development. Regarding the latter, work can develop a sense of service, justice and integrity (Melé, 2010).

For this reason, employees, social agents and companies are increasing their awareness about the importance of a thorough integration and a balance between professional life in one side and personal and family life in the other. This has been proposed in the literature as work–family balance (WFB hereinafter).

Having such an awareness and recognition of its importance reveals crucial for long-term success and companies need to make the right decisions that enable them to create a working environment that facilitates WFB. In line with this, the concept of family friendly organizational culture (FFOC) refers to the situation when companies support the integration of the employees’ work and family roles (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). Although a well-researched topic, WFB still needs further clarification, particularly in the context of SME's and family businesses. Apart from perspectives that discuss the role of gender on WFB and in particular women home-based business owners (e.g., Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Loscocco & Smith-Hunter, 2004), the literature seems to largely ignore the importance of WFB in family businesses where particular strains characterize this environment and change the WFB dynamics.

In this sense, this paper aims at analysing WFB in the context of family businesses and its impact on job satisfaction and commitment. For this purpose, the family businesses considered were classified based on the level of WFB implementation and the differences between the groups created were then investigated with regards to job satisfaction, commitment, firm size and the family generation in charge (first, second or third generation).

For this purpose, the remainder of this paper includes a review of the literature on WFB, job satisfaction and commitment in family businesses. After the analysis of the relevant literature and identification of main gaps, a methodology section explains data collection. This is followed by the analysis and discussion of results. The paper ends with a consideration of its limitations, suggestions for future research and concluding remarks emphasizing theoretical and practical implications for those who try to increase employees’ satisfaction with WFB benefits.

Work–family balanceDuring the last few decades, there has been an increase in the number of studies related to the relationships between work and non-work life (MacDermid, Pagnan, & Remnet, 2008). As a well-established research field, WFB has attracted research interest and gained increased relevance including numerous studies addressing this phenomenon from various theoretical perspectives (MacDermid, 2005). For example, Eddleston and Powell (2012) studied it from a gendered perspective; Vieira, Avila, and Matos (2012) investigated WFB it in the context of family relationships and Pillay and Abhayawansa (2014) looked at WFB from a higher education perspective, to mention only a few. These studies also cut across various disciplines such as medicine, psychology, sociology and management as well as sectors including research conducted within services (e.g. Beham and Drobnič, 2010) and manufacturing contexts (e.g., Grandey, Cordeiro, & Michael, 2007). Different countries have also been considered such as for example Germany (e.g., Beham and Drobnič, 2010), India (e.g. Woszczynski, Dembla, & Zafar, 2016), Portugal (e.g. Vieira et al., 2012) and Spain (e.g. Grau-Grau, 2013; Mayo, Pastor, Cooper, & Sanz-Vergel, 2011).

Consequently, various definitions have also been proposed. Frones (2003) defined WFB as having high levels of work–family enrichment and low levels of work–family conflict. Greenhaus, Collins, and Shaw (2003) defined WFB as the extent to which an individual is equally engaged in, and equally satisfied with his/her work role and family role. They highlight that engagement and satisfaction have to be present in both dimensions of the individual: work and family.

Work–family conflict was primordial in the research of the WFB during many years (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). The early studies on work–family conflict set the tone of the first researchers and were mainly focused on the multiple roles of the same individual (a worker that is also a father/mother, a manager, etc.) as a source of potential causes of conflict.

Since then, other elements have also been incorporated when studying WFB. Rothausen (2009) identified the main research areas related to WFB as work–family conflict as well as the gendered nature of work–family issues, and organizational responses to work–family conflict such as policies, benefits and programmes. In regards to the gendered nature of WFB, Matias and Fontaine (2015) pointed out the necessity of a gender division in the work–family context that was not followed by the same division of household tasks in the family field. Hence, the role of women is perceived as multiple (Matias & Fontaine, 2012), and they are taking higher risks of becoming overwhelmed in their attempts to reach society expectations.

It is argued here that the main components of the work–family interface are: on the one hand, work–family conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985) which defends that work and family roles and responsibilities are not compatible and, on the other hand, work–family enrichment (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006) which assumes a positive view arguing that performing multiple roles endows the individual more opportunities and resources that are transferable between those roles.

As a result, the ideal situation would be one in which the level of work–family conflict is reduced as much as possible since that it is usually strongly related with stress and negatively related to career satisfaction (Parasuraman, Purohit, Godshalk, & Beutell, 1996; Karofsky et al., 2001). According to these authors, it could be argued that the work–family conflict dimension is hindering the WFB as a whole.

Although some authors, such as Barnett and Hyde (2001) and MacDermid (2005), have demonstrated that the work–family conflict has been softened with the changing nature of work and working environments, there is still a clear impact on various organizational elements. Also from a global perspective, Chinchilla Albiol, Las Heras, Masuda, and McNall (2010) overviewed the cultural, societal, and political factors that might affect work and family relations and the main challenges and solutions that organizations have implemented to improve WFB from a positive perspective and not only conflict avoidance.

In this sense, recently, Heras, Bosch, and Raes (2015) empirically demonstrated that perceived organizational support promotes positive outcomes for employees and for companies.

Besides considering WFB as a dimension on its own, the present study focuses on WFB in the context of family businesses and its impact on other organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction and commitment. This is further explained in the following sections.

WFB and Family owned businessesWFB is already a complex topic, but it gets even more complicated in the context of family firms. This is because, according to Distelberg and Sorenson (2009), there is an overlap of roles as professionals and at the same time as members of the same family. In turn, the level of dedication and commitment expected from a member of a family will always be higher than the level expected from any other professional working in the same company but not belonging to the owning family.

In every family business, two forces coexist inside of the organization: family and business, and due to the relations of both forces, sometimes can one be dominated by the other. This happens when we have dual-earner inside of the family. Having dual-earners at home results in interplaying between the work and the family roles (Matias & Fontaine, 2015). If this situation is not well managed then it will negatively influence the harmony between the family and the professional dimension.

As Rothausen (2009) points out, it could be the case that one person is at the same time the mother and the boss of a professional. It could also happen that family members, without being involved in the direct management of the firm, can still have a decisive influence in the strategic decisions of the company. Another important aspect is the organizational culture in place. If the family business itself has a culture of masculine norms embedded in its job customs and norms (e.g., long hours implying commitment, aggressive or competitive internal culture), this may also build barriers to the full involvement of family members with balanced values (Rothausen, 2009).

Additionally, Stafford and Tews (2009) suggest that family firm's exhibit more flexibility allowing staff to bring children to the office, but they may also find it more difficult to mentally separate work life and non-work life. These authors also highlight the lack of empirical research on how members of business-owning families balance competing demands between work and the family.

A limited amount of research can be found in the literature referring specifically to WFB in family owned businesses (Rothausen, 2009; Stafford and Tews, 2009). One of the few studies on WFB in family firms showed that small family-owned businesses adopt work–family practices less than other small businesses (Moshavi & Koch, 2005).

Successful family businesses have in common the positive relationship between the family and the business (Distelberg & Sorenson, 2009) but little is still known about the presence of WFB in family firms and its implications on other factors such as job satisfaction and commitment.

Impact of WFB on other firm outcomesThomas and Ganster (1995) and Thompson and Prottas (2006) demonstrated that in companies in which managers actively supported a balance between work and family life, there were higher levels of job satisfaction and less intention to quit.

Another line of research has focused on the benefits and policies that family firms have been implementing (Kossek & Nichol, 1992; Pavalko & Henderson, 2006). Saltzstein, Yuan, and Saltzstein (2001) found that the use of various policies assumed as family friendly had very diverse effects on both employee satisfaction with WFB and job satisfaction, within and across various groups of similarly situated employees.

Aryee, Srinivas, and Tan (2005) empirically validated Frone's (2003) fourfold taxonomy of WFB. Results revealed that different processes underlie the conflict and facilitation components and that gender had only a limited moderating influence on the relationships between the antecedents and the components of WFB. Thus, they also found that work–family facilitation related to the work outcomes of job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Valcour (2007) found that working hours were negatively related to satisfaction with WFB which supports the resource drain perspective. She also found that job complexity and control over work time were positively associated with satisfaction with WFB. Thus, the control over work time moderated the relationship between work hours and satisfaction: as work hours rose, workers with low control experienced a decline in WFB satisfaction, and vice versa.

It is important to find a balance which is relevant to facilitate a sustainable human and social family capital that benefits family members and family businesses (Sharma, 2008) since ultimately work–family conflict (a dimension of WFB) has a direct impact on job satisfaction (Rothausen, 2009).

Beham and Drobnič (2010) in their study with German office workers found that perceived high organizational time expectations, psychological job demands and job insecurity had a negative relation to employees’ satisfaction with WFB. Work–family conflict partially mediated those relationships. Social support at work and job control revealed positive satisfaction with WFB, but contrary to predictions this association persisted after controlling for work–family conflict.

Analysing a group of employees in Norway, Olsen and Dahl (2010) suggest that increasing flexibility may benefit employees who work irregular hours. They demonstrated that working irregular working hours with no control over time increased sickness absence, for men. Thus, irregular hours, particularly with no flexibility, caused distress to the WFB, for both women and men. Finally, flexibility in the work schedule when working regular hours had no effect on sickness absence nor on the WFB.

The IFREI report (Informe IFREI, 2011) concluded that employee commitment was four times higher in companies in which the work environment was favourable to WFB, whereas in those that made WFB difficult, job dissatisfaction was seven times higher and employees were eleven times more likely to express the intention to quit (Ruizalba, Bermúdez-González, Rodríguez-Molina, & Blanca, 2014).

Beham, Präg, and Drobnič (2012) focused on part-time employees and demonstrated that they were more satisfied with WFB than full-time employees even after taking varying demands and resources into account. Thus, employees in marginal part-time employment with considerably reduced working hours were the most satisfied. Professionals were found to profit less from reduced working hours and experienced lower levels of WFB than non-professionals. No significant differences were found between male and female part-time workers.

In line with the empirical studies of Lings and Greenley (2005) and Gounaris (2008) about Internal Market Orientation (IMO hereinafter), Ruizalba, Bermúdez-González, et al. (2014) incorporated for the first time WFB as a new sub-dimension of the IMO model and empirically demonstrated the positive impact of WFB on job satisfaction and on employees’ commitment. IMO represents the adaptation of market orientation to the context of employer–employee exchanges in the internal market. IMO creates a relevant competitive advantage through having more satisfied and loyal customers (Lings & Greenley, 2005) and more satisfied employees (Gounaris, 2008), which in turn increased market share or profits.

Ruizalba, Bermúdez-González, et al. (2014) argued that WFB is crucial in IMO research since it is an important aspect of employees’ needs (that aim to achieve a balance between work, family and personal life). They indicate that it is difficult to say that a firm is considering the needs of their employees if they fail to include the WFB dimension. Following this line of research, the present study adopts an IMO perspective with the intention to open new avenues of research on WFB in family businesses for both scholars and practitioners interested in this field of study.

More recently, Alegre, Mas-Machuca, and Berbegal-Mirabent (2016) supported the role of WFB as an explaining factor of job satisfaction emphasizing the role of supervisors support. Based on the social exchange theory, supportive supervisor behaviours are those behaviours that supervisors display to help employees in juggling work and family demands that consist of offering emotional support (Hammer, Kossek, Yragui, Bodner, & Hanson, 2008).

MethodologyAs a result of the overview of the relevant academic literature, two key research questions were clear that referred to the level of implementation of WFB in family firms and to the impact of WFB on employee's job satisfaction and commitment in the context of family owned businesses.

In order to investigate these research questions a quantitative research strategy was implemented. A questionnaire was developed with seven-point Likert scales format, anchored by totally disagree and totally agree.

WFB has been measured with items based on the scales of Clark (2001); Kossek and Nichol (1992) and Thompson et al. (1999) including items such as: “Managers understand the family needs of employees”; “Managers support employees so that they can combine their work and family commitments”; “In this company, employees are able to find a balance between work and family life”.

Regarding job satisfaction, the items from the scale of Hartline and Ferrell (1996) were used including: “I’m satisfied with the relationship I have with my bosses”; “I’m satisfied with the support I receive from the company”; “I’m satisfied with the career opportunities I have in this company”.

For the measurement of employees’ commitment, the items from the scale of Meyer and Allen (1991) were considered including: “This company deserves that I do my best at work”; “I feel an emotional tie to the company”; “I would feel a bit guilty if I had to leave the company right now”.

To ensure the suitability of the questionnaire, a pre-test was conducted with the collaboration of 5 owners of family firms with more than 10 years of professional experience and 7 academics expert in the field.

In order to identify the configuration of the population of family businesses in Andalusia the starting point was the database Dirce (2012) and from the estimated data by the Family Business Institute that 85% of Spanish companies are family owned. Data were collected from the 8 provinces of Andalusia and keeping the same proportion of family businesses in each of the provinces regarding the total number of companies.

When identifying which are family businesses, we have taken into account that although there is some consensus that this is multifactorial and multidisciplinary; however, the concept is not without discussion (Benavides, Guzmán, & Quintana, 2011). Thus, for proper identification, two items were introduced that are considered appropriated by the literature (Comblé and Colot, 2006): capital control by the family and the active participation of the family in management of the firm. Therefore, the criteria for consideration of a firm as a family business included both requirements, and two basic criteria were adjusted: ownership and participation in the governance of the company.

A final sample of 219 Andalusian family businesses that fitted the pre-defined criteria was collected and analyzed.

Firstly, a cluster analysis was conducted that allowed the classification of companies according to their level of WFB implementation. Secondly, a description of the found groups was done, according to the level of job satisfaction, the family generation in which they are and the size of the company.

To this end, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to examine whether there were statistically significant differences in job satisfaction and commitment of employees in relation to the level of WFB applied by companies.

Finally, the relationship between the level of WFB and the family generation as well as its size was analyzed using Chi-Square.

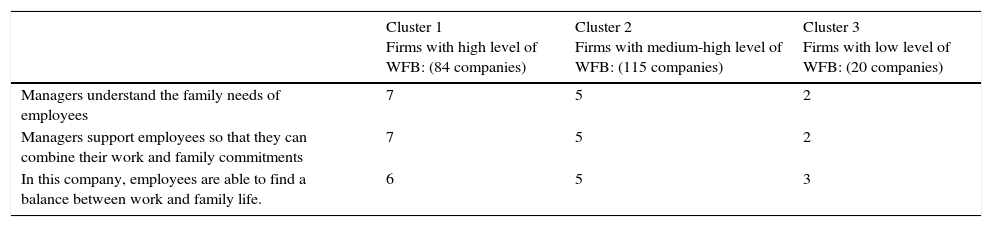

Analysis of resultsNon-hierarchical cluster analysis techniques were applied to Andalusian family companies and as a result, these were classified into 3 distinct groups (see Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the following classification was obtained: the first group is formed by 84 companies that show a high level of WFB; the second and largest group, is formed by nearly half of the sample (115 firms) with a medium-high level of WFB; and finally a small group (20 companies) integrated by firms with a low level of WFB. It can be observed, therefore, that the vast majority of Andalusian family businesses have high levels of WFB.

Final conglomerates and cases in each cluster.

| Cluster 1 Firms with high level of WFB: (84 companies) | Cluster 2 Firms with medium-high level of WFB: (115 companies) | Cluster 3 Firms with low level of WFB: (20 companies) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Managers understand the family needs of employees | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Managers support employees so that they can combine their work and family commitments | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| In this company, employees are able to find a balance between work and family life. | 6 | 5 | 3 |

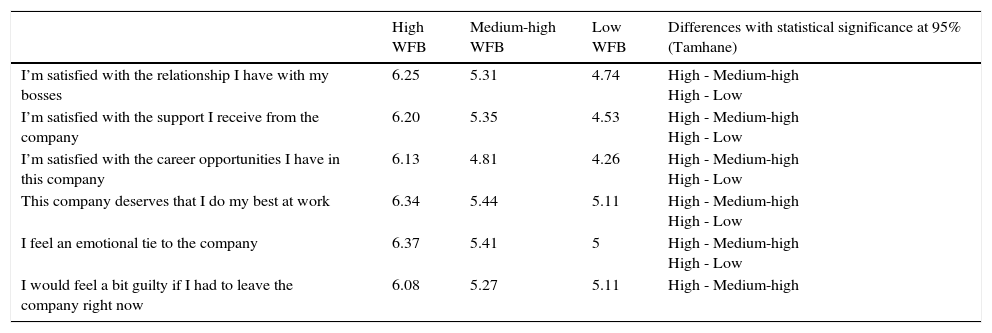

After this, a multiple analysis of variance has been done (one-way MANOVA). Following Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (2010) it is considered that it is more appropriate to initially utilize the MANOVA models when the dependent variables are highly correlated with each other. To determine the degree of inter-correlation of the six variables of choice (three items of job satisfaction and three items of commitment), a test of Barlett was conducted and the results confirm the lack of independence among themselves (850,677; d.f.=15; p-value=0.000). Therefore, an analysis of the multivariate variance was performed (MANOVA) using Wilks’ Lambda showing a value of 0.783 that is significant with an associated p-value of 0.000. Then, by ANOVA analysis and using the test post hoc of Tamhane (variances among groups are not the same), results showed significant differences in job satisfaction and employees’ commitment depending on the level of WFB implemented in firms (see Table 2). Thus, companies with high levels of WFB showed significant differences in all variables regarding companies that are still reconciling in a medium-high or low level. In contrast, no significant differences were detected amongst companies that presented a medium-high level of WFB and those with a low level of WFB.

Results of ANOVA.

| High WFB | Medium-high WFB | Low WFB | Differences with statistical significance at 95% (Tamhane) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I’m satisfied with the relationship I have with my bosses | 6.25 | 5.31 | 4.74 | High - Medium-high High - Low |

| I’m satisfied with the support I receive from the company | 6.20 | 5.35 | 4.53 | High - Medium-high High - Low |

| I’m satisfied with the career opportunities I have in this company | 6.13 | 4.81 | 4.26 | High - Medium-high High - Low |

| This company deserves that I do my best at work | 6.34 | 5.44 | 5.11 | High - Medium-high High - Low |

| I feel an emotional tie to the company | 6.37 | 5.41 | 5 | High - Medium-high High - Low |

| I would feel a bit guilty if I had to leave the company right now | 6.08 | 5.27 | 5.11 | High - Medium-high |

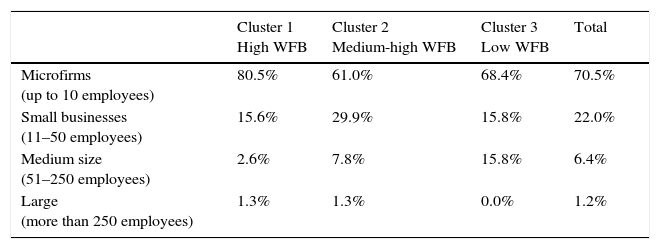

Finally, a Chi-Square analysis showed that the WFB level regarding the family generation (first, second or third generation) variables were independents, as the Chi-Square presents an associated p-value of 0.534. In contrast, for the variable size of the firm and the level of WFB the p-value is 0.092. Thus, it appears that micro-firms (up to 10 employees) are those that show a higher level of WFB, being represented in cluster 1; followed by small firms (between 11 and 50 employees) as they have higher presence in the group medium-high of WFB. Medium size companies (between 51 and 250 employees) are those that present lower levels of WFB, being overrepresented in cluster 3 (see Table 3).

Level of WFB and size of the firm.

| Cluster 1 High WFB | Cluster 2 Medium-high WFB | Cluster 3 Low WFB | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfirms (up to 10 employees) | 80.5% | 61.0% | 68.4% | 70.5% |

| Small businesses (11–50 employees) | 15.6% | 29.9% | 15.8% | 22.0% |

| Medium size (51–250 employees) | 2.6% | 7.8% | 15.8% | 6.4% |

| Large (more than 250 employees) | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 1.2% |

A limitation stems from the fact that this study has been conducted in one Spanish region, and although it represents 20% of the population of Spain, it would be interesting to extend this research to other regions. Another limitation is that the study of WFB on family owned businesses is scarce and there are still no validated measurement instruments adapted to this context. For this reason, it would be of academic interest to develop research measurement instruments for WFB adapted to the particular needs of family owned firms.

More research needs to be done to study the importance of WFB for family firms and how it affects job satisfaction, employees’ commitment and firm's performance. Much can be learned by taking seriously the role of WFB in family firms. Managers and owners of family firms could consider from a practical perspective the benefits of the implementation of WFB in their companies.

As Benavides et al. (2011) stated, in the last 47 years, in the journals that they studied, only 4 articles related to marketing in family firms were found. In order to contribute to this gap, Ruizalba, Vallespín, and González (2014) studied family firms from a marketing perspective, in particular from Internal Marketing. We hope that family firm scholars, encouraged by this positive outlook, will advance the field by making contributions to theory and practice in the discipline of Marketing in family business and in particular with more studies about the role of WFB on IMO and its consequences of job satisfaction and employees’ commitment.

Concluding remarksThis study was designed to fill a gap in the academic literature on the role of WFB in family owned firms, an area of knowledge that has so far received little attention. This paper contributes to the debate on WFB in family businesses by analysing the presence of WFB in family firms in Andalusia and by studying its influence on job satisfaction and commitment. Thus, the relationship between WFB and the size of the companies as well as the family generation is also investigated.

Main findings seem to suggest a medium presence of WFB in family firms in Andalusia. According to this study, employees of half of the Andalusian family owned businesses analyzed still do not perceive a high level of WFB and this has a relevant impact on job satisfaction and commitment, with consequences on firm performance.

It has also been found that a small difference between a medium-high level of WFB and a high level of WFB can mean a considerable increase on job satisfaction and employees’ commitment.

It is also important to highlight that there are no significant differences between job satisfaction and commitment between family firms with a medium-high level of WFB and those that have a low level of WFB.

The above summarized results reinforce the importance of proactively implementing WFB policies, programmes and benefits in family firms. This is especially relevant in particular for those firms with a medium-high level of WFB (cluster 2) as they represent 53% of the sample and with a small extra effort to increase the level of implementation of WFB the increase of job satisfaction and employees’ commitment could be quite considerable.

It is also remarkable to highlight that, unlike what would be assumed, micro-firms are those that reveal more active in the implementation of WFB.

As a concluding remark, our findings suggest that WFB has a positive impact on job satisfaction and employees’ commitment in family firms in Andalusia. This research supports therefore the crucial role of WFB in family owned businesses. As a result, family firms should take WFB facilitation more seriously, helping employees in the achievement of a balance between work, personal life and family life which in turn reflects in the bottom-line, with economic and social implications. However, what is not of minor importance, this will allow them to flourish as professionals, and as human beings.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.