This paper seeks to address the lack of empirical research on family businesses in the Spanish hotel industry. Through a hedonic price model applied to Malaga hotels, this study assessed the impact on hotel room prices of whether or not a hotel is a family business. The results show that, when being a family-business hotel is considered, this has a negative impact on prices of about €10. The results are discussed based on a combined approach of profitability, brand and price strategies, which offers several ways to interpret the research outcomes. A first option is that Malaga family businesses follow a strategy of cost leadership. The second option is heavy brand investment by Malaga family hotels. Another option is that customers consider the family hotels of this destination unprofessional compared with non-family hotels.

En este trabajo se trata de abordar la falta de investigación empírica sobre las empresas familiares en el sector hotelero español. A través de un modelo de precios hedónicos aplicado a hoteles de Málaga, este estudio evaluó el impacto en los precios de las habitaciones de hotel en función de si el hotel es o no un negocio familiar. Los resultados muestran que, el ser un hotel considerado como empresa familiar, tiene un impacto negativo en los precios de alrededor de 10 €. Los resultados se discuten tomando como base un enfoque combinado de estrategias de rentabilidad, marca y precio, que ofrece varias maneras de interpretar los resultados de la investigación. Una primera opción es que los hoteles considerados como empresas familiares en Málaga sigan una estrategia de liderazgo en costes. La segunda opción es la existencia de una fuerte estrategia de inversión en marca por parte de los hoteles considerados como empresas familiares de Málaga. Otra opción es que los clientes estimen los hoteles gestionados por familias de este destino como poco profesionales en comparación con los hoteles no considerados como empresa familiar.

Family businesses are of vital importance to the economy since they represent up to 85% of all companies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Kraus, Pohjola, & Koponen, 2012). Most businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector are family-owned (Getz & Petersen, 2004), yet there is a noticeable lack of research on family hotel businesses (Agyapong & Boamah, 2013).

Some rare journal articles have sought to fill in this research gap, such as the latest work by Banki, Ismail and Muhammad (2016) or another study by Banki and Ismail (2015), both of which have focused on Nigeria. In addition, Getz and Petersen's (2005) research compared the company growth and profit-oriented entrepreneurship of two samples of family businesses located in different countries. Other studies on this topic include Getz and Carlsen's (2000) study in western Australia, Getz and Nilsson's (2004) research on the Danish island of Bornholm and Hauck and Prügl's (2015) study in Austria.

In Spain, where tourism is a core sector (Pérez-Calderón, Ortega-Rossell, & Milanés-Montero, 2016), the percentage of family businesses reaches 89% and represents approximately 57% of the private sector's gross domestic product (Instituto de Empresa Familiar, 2015) and 66.7% of employment generation (Instituto de la Empresa Familiar, 2016). Given these statistics, tourism researchers clearly need to investigate a variety of topics within this subject area. The purpose of the present paper, therefore, is to contribute to a better understanding of whether being a family hotel influences how management determines hotel room prices.

After this introduction, the following section provides an overview of the main issues addressed in research on family business and the contextual framework of this study. “Material and methods” section then describes the hedonic price model applied, the justification of selected variables and the data sources used. In “Results” section, the main results are detailed. The implications of these results are discussed in “Discussion” section, while “Conclusion” section summarises the main conclusions.

Contextual frameworkThe literature reveals little consensus about how to define a family business (Astrachan & Shanker, 2003), so no single accepted definition is available (Agyapong & Boamah, 2013), which is one of the main problems when researching this topic (Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios, 2002). This has reduced the accuracy of any attempts to measure family business strategies’ complex influences (Rojo Ramírez, Diéguez Soto, & López Delgado, 2011).

In general, the differences in definition between studies occur as a result of which type of context is focused on by researchers. This distinction suggests three large groups of definitions centred, respectively, on property, succession and families’ ability to influence their management (Miralles-Marcelo, Miralles-Quirós, & Lisboa, 2015). These distinct focuses have led researchers to develop their own definitions of the concept of family business (Chami, 2001).

However, it is still possible to identify some commonly accepted points as to what constitutes a family business. First, these companies are controlled and managed by a family in which some members have management or decision-making responsibilities (Acquaah, 2011). Second, family businesses have a long-term orientation (Dyer, 2003; Zellweger, 2007), and managers have a greater degree of involvement in the business than they do in non-family firms (Donckels & Fröhlich, 1991; Dunn, 1996). Third, family businesses are prone to greater risk aversion (Craig & Moores, 2006) and, therefore, less innovation (Dyer, 2003). Fourth, some researchers argue that family businesses rely more on internal solutions and hire fewer service providers from outside (Donckels & Fröhlich, 1991; Fukuyama, 1998). Fifth, these companies have been found to promote better relationships with their employees, which strengthen their trust and involvement in, as well as commitment to their company (Bertrand & Schoar, 2006; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005). Last, dealings with customers are more focused on building lasting relationships rather than mere business transactions (Levering & Moskowitz, 1993; Tokarczyk, Hansen, Green, & Down, 2007), in addition to providing higher quality and more differentiated services (Carney, 2005).

Some previous studies have focused on analysing key aspects of family businesses, such as succession (Brenes, Madrigal, & Molina-Navarro, 2006; Chua, Chrisman, & Sharma, 2003; Getz & Petersen, 2004; Miller, Steier, & Le Breton-Miller, 2003; Morris, Williams, Allen, & Avila, 1997; Mussolino & Calabrò, 2014; Sharma, Chrisman, & Chua, 2003; Sund, Melin, & Haag, 2015) and leadership (Salvatico, 2006). Research has also concentrated on internationalisation (Arregle, Naldi, Nordqvist, & Hitt, 2012; Carr & Bateman, 2009; Casillas & Acedo, 2005; Scholes, Mustafa, & Chen, 2015) and risk (Claver, Rienda, & Quer, 2008), including the way in which this last affects the family's involvement in business profitability (Basco, 2013; Block, Jaskiewicz, & Miller, 2011; Massis, Kotlar, Campopiano, & Cassia, 2013; Dyer, 2006; Madison & Runyan, 2014; Mazzi, 2011; Boyle, Pollack, & Rutherford, 2011; San Martin-Reyna & Duran-Encalada, 2012; Yu, Lumpkin, Sorenson, & Brigham, 2012).

The present study is more aligned with a focus on profitability but with a specific emphasis on the key variable of price. The premise behind this approach is that, if – as Tagiuri and Davis (1996) assert – family businesses tend to be more efficient, family-owned hotels may be cheaper or might improve their contribution margin per unit, in both cases affecting profitability.

However, according to Carney (2005), family businesses also tend to offer quality services and to seek differentiation from competitors. Along the same lines, Agyapong and Boamah (2013) report that family businesses’ efficiency measures focus on creating competitive advantage by developing unique features and products. These companies also seek to improve either their quality or brand, which could increase their hotels’ prices so that they are higher or at least equal to non-family firms’ prices, thereby affecting margins and profitability. In addition, Acquaah (2011) proposes that branding and loyalty strategies are good for family businesses, and, along these lines, Tokarczyk et al. (2007) conclude that family businesses are more prone to building lasting relationships.

If brand value is considered an intangible asset (Keller & Lehmann, 2003) and a key factor in building customer loyalty (Oliver, 1997; Zeithaml, 1988), brand value would implicitly affect prices. By definition, brand value is based on price (Sweeney, Soutar, & Johnson, 1999; Tsai, 2005; Woodruff, 1997), so this value could be measured as the difference between perceived utility and price. In addition, utility as perceived by customers would be the difference between expectations and the performance experienced by consumers (Manhas & Tukamushaba, 2015). Expectations, in turn, are formed by pre-consumption experiences, adverts, word-of-mouth and product cues (Oliver, 1997).

The quality of hotels’ offer, however, is only known when the service has been consumed (Litvin, Goldsmith, & Pan, 2008), which creates costumer brand experiences and provides feedback shared with other potential customers. Extremely high expectations may favour more sales, but, according to Lee and Back (2008), a negative relationship may exist between brand awareness and brand satisfaction.

Customers’ quality perceptions depend on hotel services, so hotels need to concentrate their limited resources on developing those high-priority attributes that improve customer satisfaction (Albayrak & Caber, 2015). These services involve costs for hotels, which have to be incorporated in prices. Prices must also integrate enough of a margin to make hotels profitable.

From the research described above, it can be deduced that hotels can engage in different initiatives to improve their brand value, yet all of these strategies could affect either the price or the contribution margin. In this context, the question of whether being categorised as a family-business hotel influences room rates becomes quite pertinent. To find the answer, Rosen's (1974) well-known hedonic pricing model was used in the present study. In order to avoid geographical heterogeneity, the model was applied only in a well-known destination in Spain, namely, Malaga.

Material and methodsHedonic price modelHedonic price modelling is a technique widely used in tourism and hospitality research (e.g. Abrate, Capriello, & Fraquelli, 2011; Agmapisarn, 2014; Alegre, Cladera, & Sard, 2013; Chen & Rothschild, 2010; De la Peña, Núñez-Serrano, Turrión, & Velázquez, 2016; Falk, 2008; Fleischer, 2012; Herrmann & Herrmann, 2014; Israeli, 2002; Lee & Jang, 2011; Monty & Skidmore, 2003; Rigall-I-Torrent & Fluvià, 2011; Rigall-I-Torrent et al., 2011; Saló, Garriga, Rigall-I-Torrent, Vila, & Fluvià, 2014; Sánchez-Ollero, García-Pozo, & Marchante-Mera, 2013; Schamel, 2012; Zhang, Zhang, Lu, Cheng, & Zhang, 2011). This method is used to determine the influence on the price of certain attributes by a decomposition of the price of the goods observed by the sum of individual prices (Rosen, 1974).

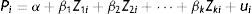

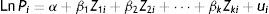

The general specifications of a hedonic price model can be represented by a linear equation expressed mathematically, as shown in Eq. (1) below, and resolved by applying ordinary least squares.

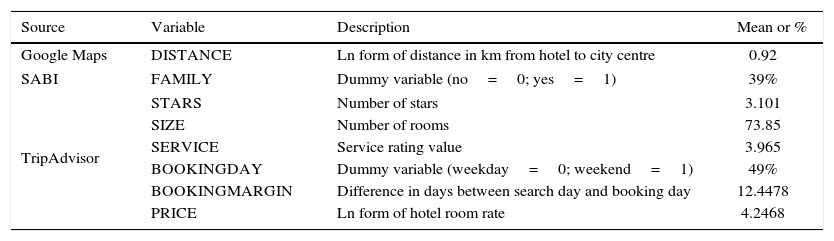

In this equation, Pi is the room price, α is the constant, Zki is the hotel room attributes and βk represents their associated coefficients. However, researchers commonly use the model described in Eq. (2) below, which, according to Rosen (1974) and Wooldridge (2009), among others, improves the model's predictive power.Variables and measuresBesides collecting data on the key variable for this study, namely, whether hotels are considered a family business or not – using the criteria established by Rojo Ramírez, Diéguez Soto, and López Delgado (2011) – data for the main variables dealt with in hedonic price research were gathered. First, the number of stars given to each hotel (STAR) was considered in previous research the most important variable in determining the price of hotel rooms (Israeli, 2002). Second, the location is, according to Abrate et al. (2011), together with hotel star category, one of the most important variables in the configuration of hotel prices. To measure this variable, each hotel's distance from the city centre (Bull, 1994) was used (DISTANCE). The hotels’ size was also collected (SIZE) as measured by the number of rooms (Zhang et al., 2011). To assess the services provided, customer ratings were used (SERVICE) since these have been utilised in previous studies (e.g. Schamel, 2012). Based on the cited research, a variable was introduced to differentiate between weekdays and weekend days (BOOKINGDAY). Finally, the booking margin (Abrate, Fraquelli, & Viglia, 2012) was included (BOOKINGMARGIN).

DatabaseData were collected during the 2014 offseason, using three main sources of data. Google Maps was used to collect the distance from the hotels to the city centre. The SABI database (i.e. the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System) was used to determine whether hotels could be considered family businesses or not, based on the criteria established by Rojo Ramírez et al. (2011). All other data (see Table 1) were collected from TripAdvisor, including hotel room prices. A total of 833 prices for all Malaga hotels were collected for subsequent regression analysis.

Brief description and descriptive values.

| Source | Variable | Description | Mean or % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Maps | DISTANCE | Ln form of distance in km from hotel to city centre | 0.92 |

| SABI | FAMILY | Dummy variable (no=0; yes=1) | 39% |

| TripAdvisor | STARS | Number of stars | 3.101 |

| SIZE | Number of rooms | 73.85 | |

| SERVICE | Service rating value | 3.965 | |

| BOOKINGDAY | Dummy variable (weekday=0; weekend=1) | 49% | |

| BOOKINGMARGIN | Difference in days between search day and booking day | 12.4478 | |

| PRICE | Ln form of hotel room rate | 4.2468 | |

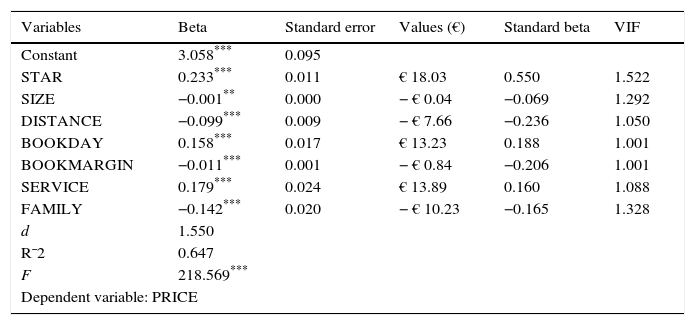

The main results from applying the hedonic price model are shown in Table 2 below. Euro-values were calculated based on the average price to facilitate an economic interpretation of the data, discriminating between continuous variables and dummy variables (Halvorsen & Palmquist, 1980). In the case of continuous variables, these represent variations in price, including marginal changes, while, for dichotomous variables, the reflected price represents the difference between whether the variables are or are not activated.

Regression values.

| Variables | Beta | Standard error | Values (€) | Standard beta | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.058*** | 0.095 | |||

| STAR | 0.233*** | 0.011 | € 18.03 | 0.550 | 1.522 |

| SIZE | −0.001** | 0.000 | − € 0.04 | −0.069 | 1.292 |

| DISTANCE | −0.099*** | 0.009 | − € 7.66 | −0.236 | 1.050 |

| BOOKDAY | 0.158*** | 0.017 | € 13.23 | 0.188 | 1.001 |

| BOOKMARGIN | −0.011*** | 0.001 | − € 0.84 | −0.206 | 1.001 |

| SERVICE | 0.179*** | 0.024 | € 13.89 | 0.160 | 1.088 |

| FAMILY | −0.142*** | 0.020 | − € 10.23 | −0.165 | 1.328 |

| d | 1.550 | ||||

| R¯2 | 0.647 | ||||

| F | 218.569*** | ||||

| Dependent variable: PRICE | |||||

Notes: d=Durbin/Watson coefficient, R¯2=corrected coefficient of determination,F=F-value.

* Statistical significance at the 95% level.

The results shown are consistent with the previous literature on hedonic pricing. As in most previous research, the variable with the greatest influence on hotel room price is hotel category (STAR), confirming a positive and significant relationship exists (Israeli, 2002; Schamel, 2012). Based on the standardised coefficients, the second variable is the hotels’ distance to the city centre, with a significant and negative relationship, a result that appears to be in line with Abrate et al.’s (2011) findings. In addition, it is important to stress the importance for room prices of customers’ ratings of hotel services. This variable (SERVICE) is ranked second in absolute terms, and, as the hotels’ distance from the city centre can hardly be altered, services are confirmed as having an important influence on hotel room prices.

Regarding the hotels’ size (SIZE), the results are consistent with previous studies’ findings (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, the outcomes of the analysis suggest that differences exist in hotel room rates between weekday and weekend days (BOOKINGDAY), similar to Schamel's (2012) findings, in which prices are higher on weekends than on weekdays. The present results also are consistent with regard to reserve margin (BOOKINGMARGIN), showing that, as a general rule, the more in advance customers book accommodations, the cheaper the hotel room is (Abrate et al., 2012).

However, what is truly interesting is the importance, significance and sign of the variable of FAMILY, which shows that hotels in Malaga categorised as family business are significantly cheaper, about €10 lower, than hotels considered non-family businesses. Based on the above-mentioned findings of previous research, this may be because family businesses tend to be more efficient (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996), and this improvement over other Malaga hotels results in lower prices. Therefore, in Malaga, family hotels may tend towards implementing a cost leadership strategy.

This appears to be in line with Acquaah's (2011) conclusion that family hotels seek to develop brand strategy and customer loyalty, as well as with Tokarczyk et al.’s (2007) report that these businesses search for long-term relationships with customers. However, the present finding could contradict previous research findings that family-owned hotels search for quality and differentiation, as reported by Agyapong and Boamah (2013) and Carney (2005). However, we could assume, as Mintzberg (1988) does, that even a cost leadership strategy provides a degree of differentiation from competitors.

A commonly accepted explanation could be that hotels classified as family businesses in Malaga are currently in a phase of heavy brand investment. This finding would reinforce what has been found in other studies about the ease with which family businesses develop a better reputation and differentiation compared with non-family companies (Carrigan & Buckley, 2008; Orth & Green, 2009; Zellweger, Eddleston, & Kellermanns, 2010). This fact, added to their greater efficiency, could allow them to gain a strong competitive advantage that may lead, in the future, to a higher room price based on a better reputation. This processes has been confirmed by numerous studies (e.g. Carmeli & Tishler, 2004; Cretu & Brodie, 2007; Weigelt & Camerer, 1988).

These hotels, thus, can capitalise on their position as family businesses (Craig, Dibrell, & Davis, 2008; Sundaramurthy & Kreiner, 2008; Zellweger, Kellermanns, Eddleston, & Memili, 2012). All of this, in addition to customers’ preference for the products and services of family businesses (Binz, Hair, Pieper, & Baldauf, 2013), could result in better performance and chances of survival for family-business hotels.

However, it is also possible that lower prices means that consumers have negative associations with family businesses, or, in other words, costumers see an added value in hotels being non-family firms due to their greater professionalism or the ability of these to attract more foreign talent. Therefore, the willingness of family businesses to seek solutions internally, as reported by Donckels and Fröhlich (1991) and Fukuyama (1998), might currently be a negative aspect of family-business hotels.

ConclusionThis paper is the first to consider the possible importance for hotel room prices of whether a hotel is categorised as a family firm. In addition, the present research focused on a destination where tourism is of great importance and where so far studies of family businesses have been limited in number. The model used also has the advantage of allowing replication in other destinations.

The results show that hotels being categorised as family businesses has, at least in Malaga, a negative impact on hotel room prices. This could have important implications, especially for brand management practices, because, until now, no study has analysed room price in reference to categorisation as a family-business hotel. This research's findings could change how hotels manage their family characteristics. A better understanding of price positioning might lead to changes in hotels’ brand strategy or the ways that family businesses interact with external agents, as well as providing greater knowledge about potential competitors in the market.

Finally, it is important to note the limitations of this study. The first of these is the difficulty of generalising the results to other destinations, so researchers are encouraged to do further research of this kind in other destinations in Spain and elsewhere. The second is that this research was conducted with low season data, so similar analysis should also be repeated in future studies to determine whether these results are insensitive to seasonality.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.