This study explores consumer ethnocentrism (CET), distinguishing between Hard Ethnocentrism (HET) and Soft Ethnocentrism (SET), and their impact on Purchase Intentions (PIN), with gender as a moderating variable. Data from 372 Latin American native consumers were collected via an electronic survey, and a Structural Equation Model (SEM) and Multigroup Analysis were conducted to test the hypotheses. The findings reveal that HET does not significantly influence PIN, while SET positively impacts it. Additionally, gender differences in ethnocentrism levels were identified. This study is the first to examine consumers who stay in their native countries rather than emigrate, offering novel insights into international marketing strategies. By aligning with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), marketers can foster positive perceptions, eliminate perceived barriers, and create impactful, gender-sensitive campaigns that resonate, particularly with female audiences.

The expansion of global markets has provided consumers with a wide range of options, encompassing both domestic and foreign products. In this context, consumer ethnocentrism (CET) plays a crucial role in international marketing, helping to explain how consumers differentiate between local and foreign products (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). CET refers to consumers' beliefs and attitudes regarding the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign-made products. It reflects a preference for the values, products, and meanings associated with one's cultural group over those of others (Dudziak et al., 2023). Consequently, ethnocentric consumers perceive outgroups negatively and avoid products linked to foreign cultures (Acikdilli et al., 2018; Aguilar-Rodríguez & Arias-Bolzmann, 2021a). These ethnocentric tendencies can significantly influence purchasing intentions (PIN).

For this study, PINs are argued in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), which posits that intention is the key predictor of actual behavior. This intention is influenced by three core factors: (1) attitude toward behavior (ATT), (2) subjective norms (SBJ), and (3) perceived behavioral control (PRV). These factors, in turn, are determined by underlying belief structures: (1) behavioral beliefs, which influence attitudes; (2) normative beliefs, which guide subjective norms; and (3) control beliefs, which affect individuals’ perceptions of their ability to control behavior. By considering internal and external factors, TPB has established itself as one of the most prominent and relevant theories for predicting people's intentions and behaviors (Negm, 2024; Zong et al., 2023).

The country of origin plays a pivotal role in shaping consumer preferences for domestic products (Aguilar-Rodríguez & Arias-Bolzmann, 2021a; Balabanis & Diamantopoulos, 2004). For instance, consumers in developing countries often display lower levels of ethnocentrism and tend to favor brands from developed nations (Reardon et al., 2005; Shoham et al., 2017). In contrast, consumers in developed countries are generally more ethnocentric, exhibiting a stronger preference for domestic products (Güneren & Öztüren, 2008). However, it is possible for consumers to simultaneously harbor strong ethnocentric feelings toward their country of origin while maintaining positive perceptions of foreign products—especially among immigrant populations (Aguilar-Rodríguez & Arias-Bolzmann, 2021a; Areiza-Padilla et al., 2021). This raises critical questions: Is CET and its influence on consumers' PIN uniform? Could consumers living in their country of origin be influenced by migrant cultures? Moreover, what about non-immigrant consumers who have never left their homeland?

While much of the literature focuses on acculturation strategies employed by immigrant consumers (Acikdilli et al., 2018; Usama et al., 2022), less attention has been given to enculturation, which refers to consumers who remain in their country of origin and whose cultural traits are deeply rooted in their environment. These traits, shaped from childhood through primary socialization, continue to influence behavior and identity throughout adulthood (Cano et al., 2020; Holloway-Friesen, 2018). Furthermore, most research on PIN among ethnocentric consumers has been conducted in industrialized nations. This study addresses this gap by examining consumers in emerging Latin American economies, where foreign brands are often perceived as superior to domestic alternatives (Batra et al., 2000; Wang & Chen, 2004). In these contexts, CET may better explain positive biases toward local products than negative biases against foreign ones (Balabanis & Siamagka, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2023).

This study posits that the level of ethnocentrism among Latin American consumers significantly influences their PIN. When consumers exhibit hard ethnocentrism, they are less likely—or unwilling—to purchase foreign products while demonstrating a clear preference for domestic or national products. Conversely, consumers are more inclined to favor foreign products when their ethnocentrism is soft. Focusing on non-immigrant consumers in developing countries, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of CET and its influence on PIN in culturally diverse and economically dynamic markets.

The Latin American consumer's significant cultural, economic, and geographic diversity creates a rich context for examining how CET manifests and influences consumer behavior. These consumers often display a duality: while ethnocentric tendencies reinforce preferences for domestic products, perceptions of foreign goods as symbols of quality or status remain pervasive, especially among consumers with higher purchasing power (González-Cabrera & Trelles-Arteaga, 2021; Kandogan, 2020).

Ethnocentric consumers in Latin America may associate domestic products with national pride and cultural heritage, yet external influences such as globalization, economic crises, and online commerce increasingly shape their choices. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Colombia, attitudes toward online shopping significantly impacted consumer behavior, overshadowing traditional drivers like the country of origin (Camacho et al., 2022). Additionally, crises involving global brands evoke more robust negative responses due to heightened consumer expectations, while local brands benefit from ethnocentric preferences in their recovery strategies (Sayin et al., 2024; Zolfagharian et al., 2020). By focusing on these dynamics, this study highlights the critical role of CET in shaping PIN, particularly in emerging markets where cultural identity and global influences coexist, providing actionable insights for international marketing strategies.

This study also examines the role of gender in moderation of the relationship between CET and PIN. Existing literature suggests that women tend to exhibit higher ethnocentrism than men (Balabanis & Siamagka, 2022; Durço et al., 2021), which often leads to a stronger preference for domestic products. However, the direct impact of gender on ethnocentrism levels remains a topic of debate (Felix, 2023; Kavak & Gumusluoglu, 2007). While women are typically more open to purchasing foreign brands (Wenbo & Lee Yeoung, 2022), they may simultaneously exhibit stronger ethnocentric attitudes, placing more value on local products than men (Akbarov, 2022; Muchandiona et al., 2021; Wang, 2021).

In the context of Latin American consumers, gender could play a significant role in shaping the CET-PIN relationship. Research indicates that women in this region are more likely to associate national products with cultural and societal values, leading to a stronger preference for domestic goods and a more skeptical view of foreign alternatives (Balabanis & Siamagka, 2022; Durço et al., 2021). For women, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, there is a stronger inclination toward ethnocentrism, reflecting a desire to preserve local culture and values, which influences their preference for domestic products (Makanyeza & Du Toit, 2017; Wenbo & Lee Yeoung, 2022).

In collectivist societies, where family and societal expectations emphasize preserving national identity and cultural heritage, women's roles further reinforce these preferences (Massry-Herzallah & Arar, 2019; Roy, 2020). Conversely, men tend to display lower levels of ethnocentrism, particularly in individualistic or cosmopolitan contexts. Their openness to foreign products suggests that their PIN are driven more by pragmatic considerations or globalized consumption patterns than national pride (Cardona et al., 2017; De Nisco et al., 2020).

Furthermore, this research addresses critical gaps in the conceptualization of CET and its dimensions—hard Ethnocentrism (HET) and Soft Ethnocentrism (SET)—and explores their impact on PIN. By extending the TPB, this study demonstrates how CET dimensions influence consumption behaviors within individuals' countries of origin. These contributions offer a comprehensive framework for future research and valuable insights into consumer behavior in culturally diverse and economically dynamic markets.

From a managerial perspective, the study underscores the importance of culturally sensitive marketing strategies tailored to the Latin American context. Businesses are encouraged to integrate traditional cultural elements with global trends, segment consumers based on ethnocentrism levels, and address gender-specific preferences through targeted promotional efforts. Additionally, local manufacturing, joint ventures, and hiring local employees are recommended to align with ethnocentric values, fostering emotional connections with consumers and enhancing brand loyalty. These recommendations offer actionable guidance for companies seeking to succeed in developing economies.

The following sections of this paper will review the relevant theoretical background to inform the hypotheses and the proposed research model. The methodology will be described in detail, including the population and sample under analysis, the instruments used, and the data collection process. The hypothesis' results will be presented, followed by a discussion of these results, discussion, implications, and their conclusions. Finally, the study's limitations will be identified, and suggestions for future research will be provided.

2Theoretical background2.1Consumer ethnocentrism (CET)Initially introduced by Gumplowicz in the 19th century and later popularized by Sumner (1907), “Ethnocentrism” refers to the belief that one's social group is the central point of reference, often fostering pride in the group while devaluing others. This concept has been extended to consumer behavior, where Shimp and Sharma (1987) introduced “consumer ethnocentrism” (CET). CET is consumers' beliefs regarding the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign-made products. This tendency reflects a perception of the in-group's superiority, influencing consumer attitudes and decision-making processes (Sharma et al., 1995).

Consumers with high CET often idealize domestically produced goods while devaluing foreign alternatives, perceiving the purchase of foreign products as a threat to the national economy and cultural identity (Park & Yoon, 2017; Shankarmahesh, 2006). This perspective extends beyond economic concerns, encompassing pride in familial, religious, and patriotic values. Supporting domestic products is thus framed as a moral obligation (Karoui & Khemakhem, 2019; Kucukemiroglu, 1999).

The prevalence and intensity of CET vary across cultures, countries, and individual characteristics, significantly shaping purchase intentions for foreign goods (Bernabéu et al., 2020). For instance, consumers in developed countries often favor domestic products, associating them with superior quality (Dickson et al., 2004; Elliott & Cameron, 2010). In contrast, consumers in developing countries may display greater openness to foreign products, particularly those from developed nations, depending on factors such as brand reputation and product type (Reardon et al., 2005; Roth & Romeo, 1992).

While ethnocentrism and the country-of-origin effect influence consumer attitudes, their impact is complex and context-dependent. Research suggests that a consumer's identification with a specific country or cultural group can moderate these effects, highlighting the intricate dynamics of global consumer preferences (Kaynak & Kara, 2002, 2015; Zolfagharian et al., 2017, 2020).

Consumers with high CET prioritize the values and products of their social groups over those of others. This in-group favoritism often results in negative perceptions of out-groups, fostering psychological and emotional distance from foreign products and their associated meanings (Acikdilli et al., 2018; Tajfel, 1982). For these consumers, purchasing foreign-made goods is viewed as inappropriate and detrimental to the domestic market.

2.2Purchase Intentions (PIN)PIN is "an individual's conscious plan to make an effort to purchase a brand" (Spears & Singh, 2004, p. 56). According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), PIN is influenced by ATT, which refers to the extent of favorable or unfavorable feelings toward an object. Behavioral intentions, including PIN, represent a person's intention to perform specific actions. PIN, therefore, reflects personal action tendencies related to a brand, with ATT serving as a summary evaluation of the brand that influences these tendencies. Essentially, PIN captures an individual's motivation to engage in a specific purchasing behavior (Bagozzi & Burnkrant, 1979).

However, ATT alone is not sufficient to predict behavior. Ajzen and Fishbein (1977), argue that normative beliefs, or perceptions of others' behavioral expectations, drive people to act under social pressure. These social norms (SBJ) influence PIN (Aguilar-Rodríguez & Arias-Bolzmann, 2021b; Jia et al., 2023). Ajzen (1991), also emphasizes the role of PRV in shaping intentions and behaviors. Individuals with higher levels of self-control are more likely to act on their intentions, provided they have both the ability and motivation to perform the behavior (Ajzen, 1991, 2002a, 2002b; Zhou et al., 2013). Thus, PIN is a form of planned behavior that can result in actual purchase decisions.

To explain these dynamics, Ajzen and Fishbein (1977) introduced the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which posits that ATT and SBJ jointly determine behavioral intentions, mediating between these factors and the resulting behavior. Ajzen later expanded this framework with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by incorporating PRV as a critical determinant of intentions and actions (Ajzen, 2002a, 2012). In the TPB framework, behavioral intentions are shaped by three elements: (1) ATT toward the behavior reflects an individual's positive or negative evaluation of an action based on beliefs about its potential outcomes. Favorable attitudes increase the likelihood of performing the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). (2) SBJ involves perceived social pressure to act in a certain way, influenced by the expectations of significant others (Ajzen, 2012). (3) PRV pertains to an individual's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior, which impacts both the intention and actual execution of the action (Sniehotta et al., 2014).

The TPB improves upon the TRA by addressing limitations related to voluntary control, considering external and internal constraints such as resources, skills, and environmental barriers (Sniehotta et al., 2014). Additionally, it provides actionable insights for designing interventions identifying whether ATT, SBJ, or PRV changes are needed to encourage desired behaviors. Furthermore, the TPB explains unconscious consumer behavior, where emotions or situational factors may temporarily shift ATT and influence decisions (Saxena & Sharma, 2023; Yadav & Pathak, 2016).

Empirical studies reinforce the relevance of TPB in understanding consumer PIN. For instance, a study of Muslim consumers in Germany found that positive ATT toward consumption, compliance with social norms (SBJ), PRV about consumption, and product availability were significant predictors of PIN (Sherwani et al., 2018). Similarly, research on Thai consumers aged 18 and older, with at least a high school education, identified ATT, SBJ, and PRV as significant positive influences on PIN for organic products (Maichum et al., 2016). Among Korean-American consumers, PIN reliably reflected actual purchasing behavior (Lee et al., 2018).

Cultural factors further shape PIN, particularly for organic products. ATT toward green products and SBJ are significant predictors of PIN, with SBJ exerting a more substantial influence. Although PRV also positively correlates with PIN, its impact is moderated by the combined effects of ATT and SBJ (Calvo-Porral & Lévy-Mangin, 2017; Muk et al., 2019).

2.3Consumer ethnocentrism (CET) and Purchase intentions (PIN)According to previous findings, a positive relationship exists between CET and PIN. In a recent study of Swedish and Finnish consumers regarding national airlines, CET was found to directly increase PIN and indirectly improve PIN by enhancing consumer perceptions. However, the positive effect of CET on PIN was weaker among frequent travelers (Felix, 2023). Aguilar-Rodríguez and Arias-Bolzmann, (2021a) found that while there is a positive relationship between CET and PIN, it depends on whether consumers are in their country of origin or a host country. Explaining consumer bias in favor of domestic products depends on the country of origin (Balabanis & Diamantopoulos, 2004; Karoui & Khemakhem, 2019).

Jia et al. (2023), discovered that CET and judgments about national products act as motivational and cognitive factors, mediating the relationship between social norms and national purchase intention. Zeugner-Roth et al. (2015), identified that national identity has a more substantial impact than CET on consumers' willingness to buy national products. Kandogan (2020), noted that consumers in developed countries favor foreign products over domestic ones and are less open to imports from other developed countries, whereas emerging countries are more welcoming to imports from other emerging trading partners. Consequently, consumers from underdeveloped countries exhibit low ethnocentrism and prefer brands from developed countries (Reardon et al., 2005; Shoham et al., 2017). Highly ethnocentric consumers are more likely to purchase domestic products (Güneren & Öztüren, 2008). Furthermore, entrepreneurs incorporate individual, social, and cultural signals from consumers to inform their judgments and actions (Niemi et al., 2022).

Other studies have identified that CET inversely influences consumers' willingness to purchase foreign products (Abdul-Latif et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2023). However, consumer intention positively influences purchasing behavior (Muchandiona et al., 2021). For Vietnamese consumers, CET negatively affected the perception of the country's image and purchase intention towards Chinese imported products (Nguyen et al., 2023). Consumers with high levels of CET exhibit weak affection and trust towards the country of origin. However, associations with products from the country-of-origin influence consumer trust and price perception, affecting purchase intention (Li & Xie, 2021). Thus, consumers primarily depend on the brand's country rather than the country of origin, with their attitudes and purchases reflecting brand perceptions (Story & Godwin, 2023; Tomić Maksan et al., 2019).

Chryssochoidis et al. (2007) found that CET affects consumers' beliefs and how they evaluate the perceived quality of domestic and foreign products. They divided CET into Hard Ethnocentrism (HET) and Soft Ethnocentrism (SET). HET refers to strongly nationalistic behavior and an almost hostile attitude towards foreign products, which are considered harmful to society. SET, on the other hand, involves moderate behavior, emphasizing a preference for national products without inciting a general rejection of foreign products.

In line with these findings, Miguel et al. (2023) observed that SET was predominant among Portuguese consumers. Durço et al. (2021) evaluated distinct levels of CET among Argentines, Uruguayans, and Brazilians, and found that consumers with HET declared themselves conservative and preferred national products, emphasizing taste, quality, and nationalism. In contrast, consumers with SET were considered liberal and had higher education levels, showing favorable attitudes and intentions towards imported products due to perceived quality improvements, though patriotic behavior was also evident. Nonetheless, brand benefits and product features are critical factors that affect consumer purchase intention (Akbarov, 2022; Akkaya, 2021).

Therefore, the following hypotheses are established:

Hypothesis 1: A relationship exists between CET (HET/SET) and PIN of Latin American native consumers.

The literature shows that gender significantly influences CET (Akbarov, 2022; Muchandiona et al., 2021; Wang, 2021). It is known that there are differences in ethnocentric levels between men and women (Güneren & Öztüren, 2008). Women develop positive feelings toward foreign products compared to men (Hult et al., 1999), although they are also known to have greater ethnocentric feelings than men (Balabanis et al., 2002; Shimp & Sharma, 1987). It has recently been identified that older, less educated, and lower-income American women likely have a stronger national identity (Choi, 2017), although other contributions have revealed that gender has no direct effects on CET (Bizumic, 2019; Felix, 2023).

In developing countries, gender has not been a determinant of CET either (Cazacu, 2006; Makanyeza & Du Toit, 2017). For example, Makanyeza and Du Toit (2017) found that gender did not moderate the effect of CET on ATT. In fact, the study found that CET had a negative effect on ATT, while ATT had a positive effect on PIN. Durço et al. (2021) found that women show more ethnocentric ATT than men and evaluate national products more favorably than foreign ones.

On the other hand, gender is a factor that influences PIN (Negm, 2024). Dudziak et al., (2023) found that shopping habits vary, with hypermarkets and local stores popular with both men and women. For their part, Kavak and Gumusluoglu (2007), identified that men prefer national food and women prefer foreign food. In Chinese consumers, it was identified that women are more willing to buy foreign brands than men, in addition, women with global citizenship consumer thinking are more willing to buy foreign brands than men (Wenbo & Lee Yeoung, 2022). In fact, for consumers with high SBJ knowledge, the effect of associations of products related to the country of origin on price perception is weaker, although its effects are the same when the gender of the consumers is intervened (Li & Xie, 2021).

Given these diverse findings, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 2: The association between CET (HARD/SET) and PIN of Latin American native consumers is moderated by gender.

The theoretical research model of the study is as in Fig. 1.

3Data and MethodThe conceptual model is tested through an online survey of Latin American native consumers. This research employed a non-experimental, cross-cultural, and correlational design with a single-sample approach. The study uses snowball sampling. This sampling technique was critical to recruitment and data quality, highlighting the importance of cultural sensitivity (Goodman, 1961). The data were processed in SPSS (IBM, 2023), contemplating as a first phase, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and then, in a second phase, carrying out a Structural Equations Model (SEM) and a Multigroup Analysis in Amos, using gender as a moderating variable (Gaskin & Lim, 2016; Lowry & Gaskin, 2014). This approach aligns with the recommendations of Iacobucci (2009, 2010), which advocates for the use of such models as suitable and effective tools for analyzing consumer behavior.

3.1ParticipantsThe study participants were native Latino consumers who lived in their country of origin and had not emigrated, meaning they have remained in their home country since birth. These participants were selected because they belong to a cultural group with a strong connection to their country of origin, where economic, cultural, and geographic differences are pronounced. This helped ensure a sufficiently large and diverse sample. As Kandogan (2020) noted, Latin America tends to show a more significant overall attraction to imported products than other regions.

The sample revealed that 97% of participants were born in South American countries: Argentina (10%), Chile (16%), Colombia (22%), Ecuador (33%), Peru (25%), and Venezuela (17%). The remaining 3% were from Central America, with participants from Nicaragua (1%) and Panama (2%). None of the participants selected "other gender" or "prefer not to say" as their gender response, and therefore, the sample consisted of nearly equal proportions of women (51%) and men (49%) out of 372 participants.

To control potential gender influences on the results, the number of participants from each gender in the sample was balanced, ensuring no bias toward either group. Gender was not only controlled to ensure unbiased and meaningful findings, but it also emerged as a key variable in understanding its influence on consumer behavior. It guaranteed its inclusion in moderation and multigroup analyses in section 4.3. By incorporating gender, the study advances theoretical models and provides deeper insights into the cultural dynamics that shape purchase intentions.

The sample also revealed that 95% of participants were between 25 and 48 years old, reflecting a well-distributed age and gender balance. In terms of marital status, most participants were single (55%), followed by married (22%), cohabiting (12%), and separated (12%). A significant majority (68%) were college graduates, which aligns with trends in international marketing research, as more educated individuals are often overrepresented in such studies and are of particular interest to international marketing professionals (Banna et al., 2018). Table 1 provides the detailed demographic characteristics of the study sample.

Participants’ characteristics of demographic variables (n = 372).

| Marital status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Level Education | Single | Married | Common law marriage | Divorced |

| Female | High school | 51 | 8 | 7 | 0 |

| Bachelor's degree | 40 | 19 | 10 | 9 | |

| Master's and doctoral degree | 11 | 17 | 6 | 10 | |

| Total | 102 | 44 | 23 | 19 | |

| Male | High school | 30 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Bachelor's degree | 57 | 15 | 6 | 7 | |

| Master's and doctoral degree | 16 | 14 | 7 | 10 | |

| Total | 103 | 37 | 20 | 24 | |

Participants were recruited through electronic surveys in Microsoft Forms from February to October 2023. Given the limited access to a cultural population, snowball sampling was used as the recommended sampling technique for cultural studies (Acikdilli et al., 2018; Aguilar-Rodríguez & Arias-Bolzmann, 2021a, 2021b), allowing the researcher to use intact groups of subjects and collect a large amount of information and overcome limited access to a Latino population concentrated in a single country. Snowball sampling is a non-probability technique that can be helpful when the population is difficult to reach (Goodman, 1961). Multiple entry points into the native Latino community were used to reduce the selection bias inherent in this method, and a wide range of people was chosen to provide more contacts (Atkinson & Flint, 2001; Bloch, 2007).

Snowball sampling was implemented by initially identifying a reference group of active members from Latino communities on social networks such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram, focusing on topics relevant to native Latinos. These individuals were directly contacted through personalized messages, emails, and study invitations, explaining the research objectives, and highlighting the importance of their participation. They were provided with a link to the online survey and asked to share it within their networks with others who met the study criteria, thus encouraging participation and dissemination. The survey distribution was monitored using a tracking system, and if response rates were insufficient, reminders were sent, or new starting points within the network were contacted to increase participation.

Participants were assured that their responses would be confidential and would not be used to identify them individually. Three follow-up emails were sent so that participants who still needed to complete the surveys could do so within that time. These emails were sent in April, July, and September. As a result, in the current study, a total of 495 responses were collected, of which only 372 were considered valid after an analysis to detect missing values and outliers, being identified as a representative sample (Hair et al., 2014; Sarstedt et al., 2017). It used the common method bias with Harman's single factor score (Podsakoff et al., 2003, 2012), where the factor matrix was far than 50%, so it is that no existing threat that affects the data, also helping in the sample representativeness.

To mitigate CMB, it incorporated the recommendations of Jordan and Troth (2020) by balancing positively and negatively worded items in the instrument, as detailed in Section 3.3. This design included reverse-coded items to ensure that the wording of some statements was intentionally reversed, balancing item phrasing without compromising the scale's content validity or conceptual integrity or causing confusion for respondents. As Baumgartner and Steenkamp (2001), suggest that response styles can introduce bias into questionnaire ratings, thereby threatening the validity of conclusions drawn from marketing research data. Including reverse-coded items disrupts CMB response patterns, encouraging participants to engage more thoughtfully with the questions.

3.3MeasuresThe instrument was composed of four sections. The first section featured a pre-selection filter question designed to assess the participants' level of cultural identification: "How important do you consider your Latino cultural identity in your daily life?", measured on a 7-point Likert scale. This question helped identify the strength of participants' cultural attachment. Additionally, it inquired whether participants had ever lived outside their country of origin for more than 12 months. Participants who demonstrated a high level of cultural identification and who had not spent more than 12 months abroad were considered eligible for inclusion in the sample. The second section gathered demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, education level, and country of origin. In the second section, statements related to CET towards their country of origin were presented based on the Consumer Ethnocentric Tendencies Scale (CETSCALE), developed by Shimp and Sharma (1987), which consists of 17 items under the subsets proposed by Chryssochoidis et al. (2007): (1) HET, and (2) SET. In the third section, 13 items were adapted from different statements about the PIN, using the scale developed by Ajzen (1985, 2015); Fishbein and Ajzen(1975); Hill et al. (1977). These items captured key constructs of the TPB: (1) ACT, (2) SBJ, (3) PRV, and (4) PCH. All statements were measured using 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

The questionnaire was translated into Spanish by an experienced native translator using back-translation and adjusting coherence to reflect the idiosyncrasies of the language. This translation process helps preserve the original meaning and connotations of the measurement items (Ozolins et al., 2020). This approach is critical for ensuring accuracy and consistency, especially in multicultural or multilingual studies. Maintaining the intended meaning across languages reduces the risk of misinterpretation in diverse cultural contexts (Toma et al., 2017). Forward translation plays a vital role by adapting the content to align with cultural nuances and practical relevance while preserving the original intent. As part of the procedure, forward translation involved translating the questionnaire from its original language into Spanish carefully adjusting terms and phrases to ensure cultural appropriateness and clarity for the target audience. Scores for each scale were calculated using participants' average item scores based on previous research (Cleveland et al., 2015). The reliability of all measures was tested, using Cronbach's alpha (α) for that purpose, showing sufficient internal consistency (α>0.7).

4ResultsThis research utilized a rigorous analytical framework to ensure the validity and reliability of its findings. Although the research instruments were previously validated, the inclusion of diverse cultural groups necessitated an EFA to verify the appropriateness of items across varying cultural contexts and identify underlying data structures. EFA facilitated the determination of key factors explaining the variance in observed variables (Ullman, 2006), while a subsequent CFA validated the measurement model, ensuring alignment between observed data and theoretical constructs (Hoyle, 2015). Together, EFA and CFA established a robust foundation for SEM, enabling the development of a reliable and theoretically sound model (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2019). This sequential approach enhanced the precision of the study's results, contributing valuable insights to cross-cultural consumer behavior research.

4.1Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed, which determined a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (KMO) of 0.919 (Sig. > 0.8) (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2010; Hoyle, 2015) and a Bartlett's Test of Sphericity with a significance level of 0.000. Using the Principal Components Extraction Method with Varimax rotation, the total explained variance was 64.841% for three constructs: (1) HET (11 items), (2) SET (6 items), and (3) PIN (13 items).

To validate the measurement model, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed, assessing the statistical reliability and fit of the proposed constructs (Hoyle, 2015; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2006; Ullman, 2006). The CFA results led to the refinement of the scales, retaining 8 items for HET, 3 items for SET, and 9 items for PIN. The item reduction process was based on the following statistical criteria:

HET: Three items were removed due to low factor loadings (< 0.50) and high cross-loadings with other factors, indicating insufficient discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2010; Powell, 1992).

SET: Three items were eliminated based on their standardized residual covariances exceeding the threshold of 2.58 (Byrne, 2010), suggesting a lack of consistency with the underlying construct.

PIN: Four items were excluded, primarily those associated with SBJ in the Theory of Planned Behavior model. These items exhibited weak standardized factor loadings (< 0.40), high modification indices (> 15), and low squared multiple correlations (< 0.30), indicating limited contribution to the construct's explanatory power. Table 2 shows the resulting items in measurement, with their mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach's α.

Table 2.Questionnaire items with their mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach's α of the constructs.

Constructs Codes Measuring items Mean SD Cronbach's α Hard ethnocentrism (HET) HET1 Purchasing foreign-made products is unpatriotic. 2,70 1,301 0,934 HET2 It is not right to purchase foreign products, because it is out of jobs. 2,80 1,315 HET3 A real Latin American should always buy your country's product. 2,85 1,347 HET5 Those born in this country should not buy foreign products because this hurts local businesses and causes unemployment. 2,65 1,359 HET6 Curbs should be put on all import. 2,29 1,370 HET7 Foreigners should not be allowed to put their products on our markets. 2,34 1,325 HET8 Foreign products should be taxed heavily to reduce their entry into this country. 2,66 1,417 HET9 Consumers who purchase products made in other countries are responsible for putting their fellows out of work. 2,37 1,391 Soft ethnocentrism (SET) SET2 Only those products that are unavailable in this country should be imported. 3,40 1,340 0,758 SET4 National products, first, last, and foremost. 3,56 1,175 SET5 It is always best to purchase national products. 3,58 1,157 Purchase intentions (PIN) ATT1 I think that purchasing a national product is favorable. 3,88 1,206 0,921 ATT2 I think that purchasing a national product is a good idea. 3,92 1,107 ATT3 I think that purchasing national products is safe. 3,65 1,072 PRV2 I see myself as capable of purchasing national products in future. 4,00 1,090 PRV3 I have the resources, time, and willingness to purchase national products. 3,82 1,109 PRV4 There will be plenty of opportunities for me to purchase national products. 3,77 1,067 PCH1 I intend to purchase national products next time because of their positive contribution. 3,84 1,114 PCH2 I plan to purchase more national products rather than foreign products. 3,72 1,106 PCH3 I will consider switching to foreign brands. 3,62 1,133

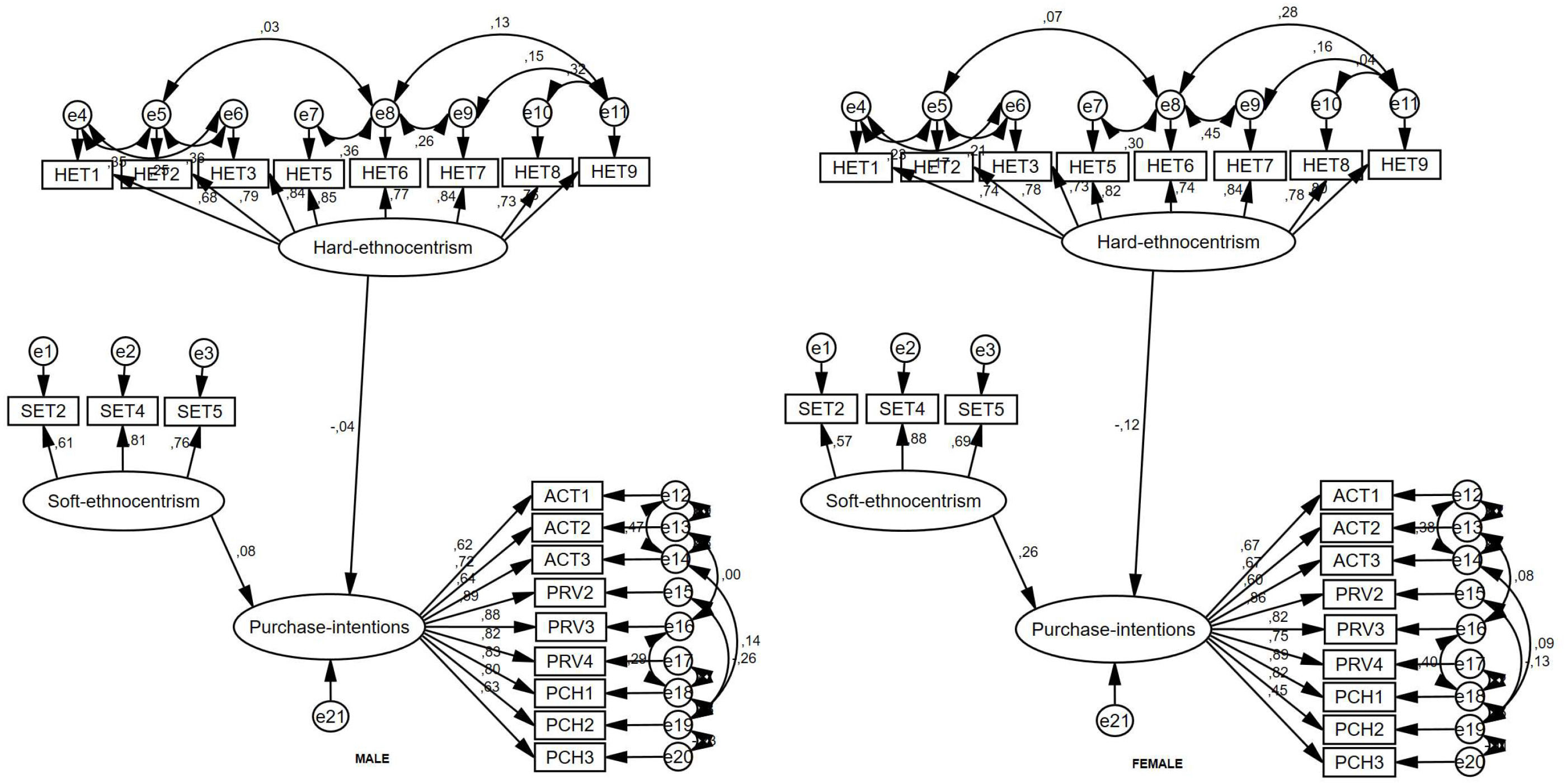

All retained factors demonstrated satisfactory reliability, with Cronbach's alphas exceeding 0.70, confirming internal consistency (Hair et al., 2019). The final model exhibited a firm fit, with all standardized factor loadings in Fig. 2 being statistically significant (Sig.<1). Additionally, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.90) confirmed the adequacy of the model hypotheses with the sample data.

Discriminant validity (AVE), as measured by Average Variance Extracted (AVE), exhibited robust correlations with each factor, surpassing the threshold of 0.5 (AVE>0.5) (Cachón-Rodríguez et al., 2024). Currently, composite reliability (CR) demonstrated significance, surpassing the 0.7 criterion (CR>0.7) (Hair et al., 2019). These findings collectively affirm the presence of an acceptable measurement model, as illustrated in Table 3 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2006).

Validity analysis of the model.

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | PI | SE | HE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIN | 0.924 | 0.581 | 0.027 | 0.939 | 0.762 | ||

| SET | 0.764 | 0.524 | 0.498 | 0.787 | 0.165* | 0.724 | |

| HET | 0.934 | 0.640 | 0.498 | 0.936 | -0.005 | 0.706*** | 0.800 |

Notes: CR=Critical Region, AVE=Average Variance Extracted, MSV=maximum shared variance, MaxR(H)= maximum reliability.

PI=Purchase Intentions, SE=Soft Ethnocentrism, HE=Hard Ethnocentrism

Significance of correlations: *p<0,050; *p<0,010; ***p<0,001

The study conducted a measurement invariance analysis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in AMOS (Byrne, 2010; Kline, 2016) to ensure the validity of cross-group comparisons. Establishing measurement invariance is essential to confirm that observed differences in structural relationships stem from substantive differences in the constructs rather than inconsistencies in their measurement (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Putnick & Bornstein, 2017).

The analysis followed a hierarchical three-step procedure: (1) Configural Invariance: A baseline model was estimated separately for each gender group to assess whether the factorial structure remained consistent across groups. Model fit indices (CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, SRMR ≤ 0.08) indicated an acceptable fit, confirming that both groups conceptualized the constructs similarly (Byrne, 2010; Clench-aas & Bang-Nes, 2011). (2) Metric Invariance (Weak Invariance): Factor loadings were constrained to equality across gender groups to determine whether respondents interpreted the measurement items consistently. The invariance assessment met recommended thresholds, as evidenced by a negligible change in the Comparative Fit Index (ΔCFI < 0.01) and a non-significant chi-square difference test (Δχ², p > 0.05), supporting the equivalence of factor loadings across groups(Schmitt & Kuljanin, 2008; Vandenberg et al., 2000). (3) Scalar Invariance (Strong Invariance): Further constraints were applied to both factor loadings and item intercepts to assess whether latent mean differences could be meaningfully compared. The model retained adequate fit criteria (ΔCFI < 0.01, RMSEA ≤ 0.08), indicating that any observed differences in latent variable means reflected genuine group differences rather than measurement bias (Byrne, 2010; Putnick & Bornstein, 2017).

The successful establishment of both metric and scalar invariance substantiates the robustness of gender-based multi-group comparisons, ensuring that gender can be examined as a valid moderating variable within the structural model (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Schmitt & Kuljanin, 2008). Table 4 presents the measurement invariance results at each step.

MICOM measurement invariance results.

| Step | Fit indices | Thresholds | Obtained values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural Invariance | CFI: Comparative fit index | ≥0.90 | 0.939 | Suitable |

| TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index | ≥0.90 | 0.922 | Suitable | |

| RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation | ≤0.10 | 0.075 | Suitable | |

| NFI: Relative fit index | ≥0.90 | 0.902 | Suitable | |

| Metric Invariance | ΔCFI: Comparative Fit Index | <0.01 | 0.004 | Suitable |

| Δχ² (p-value): Change in chi-square, with p-value | p >0.05 | 2.43 (p = 0.114) | Suitable | |

| Scalar Invariance | ΔCFI: Comparative Fit Index | <0.01 | 0.003 | Suitable |

| RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation | ≤0.10 | 0.077 | Suitable |

Note: Acceptable thresholds are based on established standards for SEM invariance testing.

The results confirm that the measurement model maintains an equivalent factor structure across gender groups (Configural Invariance), that measurement items are interpreted consistently (Metric Invariance), and that observed differences in latent means are attributable to substantive differences rather than measurement artifacts (Scalar Invariance). Thus, gender-based comparisons within the structural model are statistically valid.

4.3Structural Equations ModelFig. 3 presents the SEM. The modification of indices was used, which suggested correlating some related measurement errors in the HET, SET, and PIN factors. The standardized estimators showed statistical significance (Sig.<1). (Kline, 2011; Lowry & Gaskin, 2014; Sarstedt et al., 2017).

The SEM showed adequate indicators of goodness of fit that are presented in Table 5.

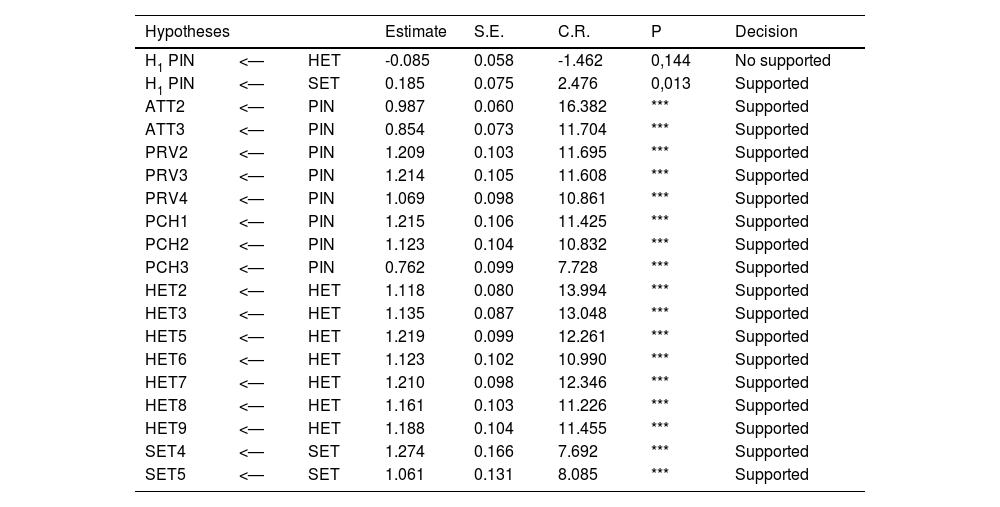

Table 6 presents the regressions for each relationship. All HET, SET, and PIN dimensions showed statistical significance at 99% (p-value<0.001) (Henseler et al., 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999). SE positively influences CP, but HET has no significant influence on PIN.

Unstandardized coefficients and their statistical significance.

| Hypotheses | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PIN | <— | HET | -0.085 | 0.058 | -1.462 | 0,144 | No supported |

| H1 PIN | <— | SET | 0.185 | 0.075 | 2.476 | 0,013 | Supported |

| ATT2 | <— | PIN | 0.987 | 0.060 | 16.382 | *** | Supported |

| ATT3 | <— | PIN | 0.854 | 0.073 | 11.704 | *** | Supported |

| PRV2 | <— | PIN | 1.209 | 0.103 | 11.695 | *** | Supported |

| PRV3 | <— | PIN | 1.214 | 0.105 | 11.608 | *** | Supported |

| PRV4 | <— | PIN | 1.069 | 0.098 | 10.861 | *** | Supported |

| PCH1 | <— | PIN | 1.215 | 0.106 | 11.425 | *** | Supported |

| PCH2 | <— | PIN | 1.123 | 0.104 | 10.832 | *** | Supported |

| PCH3 | <— | PIN | 0.762 | 0.099 | 7.728 | *** | Supported |

| HET2 | <— | HET | 1.118 | 0.080 | 13.994 | *** | Supported |

| HET3 | <— | HET | 1.135 | 0.087 | 13.048 | *** | Supported |

| HET5 | <— | HET | 1.219 | 0.099 | 12.261 | *** | Supported |

| HET6 | <— | HET | 1.123 | 0.102 | 10.990 | *** | Supported |

| HET7 | <— | HET | 1.210 | 0.098 | 12.346 | *** | Supported |

| HET8 | <— | HET | 1.161 | 0.103 | 11.226 | *** | Supported |

| HET9 | <— | HET | 1.188 | 0.104 | 11.455 | *** | Supported |

| SET4 | <— | SET | 1.274 | 0.166 | 7.692 | *** | Supported |

| SET5 | <— | SET | 1.061 | 0.131 | 8.085 | *** | Supported |

Note: Significance of correlations: †p<0,100; *p<0,050; **p<0,010; ***p<0,001

The data were grouped according to the gender of the participants studied. The decision to include gender in this analysis was made to identify whether there was gender-specific effects in the relationships under investigation. Fig. 4 shows that for males, there was a negative correlation between HET and PIN of -0,04 and between SET and PIN of 0.08. In females, it was found that HET and PIN were negatively correlated with –0.12 and between SET and PIN with 0.26. Although all the dimensions had similar behavior in their indicators, females showed a greater incidence between SET and PIN.

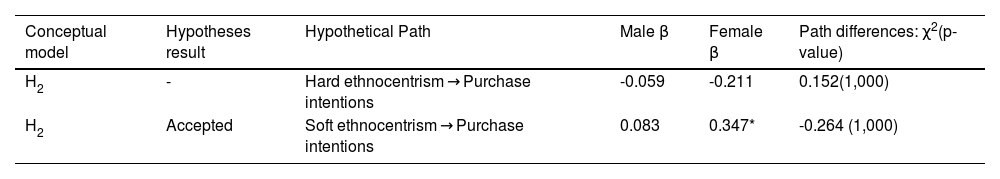

Table 7 shows the standardized coefficients with their respective P-value, where it is determined that the female of the participants is significant at 95% (P-value<0.050) in the relationship between SET and PIN.

Regression weights with standardized coefficient and P-value for moderating variable.

| Relations | Estimate | P-value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating variable - Male | |||

| H2 PIN<—HET | -0.030 | 0.709 | No supported |

| H2 PIN<—SET | 0.071 | 0.456 | No supported |

| Moderating variable - Females | |||

| H2 PIN<—HET | -0.103 | 0.200 | No supported |

| H2 PIN<—SET | 0.276 | 0.013* | Supported |

Notes: Significance of correlations: †p<0,100; *p<0,050; **p<0,010; ***p<0,001.

Table 8 shows the differences between the groups classified by gender. Considering that the p-value of the chi-square difference test is significant at 99% (p-value <0.001), it is evident that there are differences in the relationships between SET and PIN only for females. The analysis identified significant interaction effects between SET and PIN, specifically for women. This indicates that when the interaction term's coefficient (β) is statistically significant, the relationship between SET and PIN is influenced by gender, demonstrating that gender serves as a moderator. To mitigate multicollinearity issues—common when interaction terms are included, each variable was centered before computing the interaction term (Baron & Kenny, 1986). This process involved subtracting the mean of each variable from its observed values, ensuring that the resulting interaction term reflects the moderated relationship without distorting the stability of the regression coefficients (Burks et al., 2019; Cachón Rodríguez et al., 2019).

Multigroup test for gender.

| Conceptual model | Hypotheses result | Hypothetical Path | Male β | Female β | Path differences: χ2(p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | - | Hard ethnocentrism → Purchase intentions | -0.059 | -0.211 | 0.152(1,000) |

| H2 | Accepted | Soft ethnocentrism → Purchase intentions | 0.083 | 0.347* | -0.264 (1,000) |

Notes: Significance indicators: p<0,100; *p <0,050; **p<0,010; ***p<0,001. (1) The positive relationship between PIN and SET is only significant for Female. (2). There is no difference.

The research examines the influence of ethnocentrism on the purchase intentions of foreign products in Latin American native consumers residing in their countries of origin. The study delves into how these consumers' ethnocentrism is influenced by the specific characteristics of their respective countries of origin, which affects their PIN despite sharing the same geographic region. These findings become essential, given the increasing ethnic diversity in consumer markets.

Contrary to the assumption suggested that Latin American consumers with high levels of ethnocentrism would have a lower propensity to purchase foreign products due to their strong preference for domestic products, which would generate a negative relationship between HET and PIN, the results show that when consumers have high levels of ethnocentrism, their purchase intention is not negatively affected. Therefore, these results suggest that a higher level of ethnocentrism among Latin American consumers does not influence their preference for foreign products. Despite sharing cultural similarities, the multiculturalism of these markets has caused changes in their attitudes and consumption patterns.

Although Latin American consumers maintain ethnocentric solid ties with their countries of origin, the reality of being part of an increasingly globalized and interconnected society has caused their consumer preferences to be inclined toward acquiring foreign products. Conversely, affinity with their country of origin and national identification can mitigate negative perceptions about national products by perceiving themselves as part of the culture. Although the HET was anticipated to hurt PIN, the findings indicate that Latino consumers are quite pragmatic in their decision-making process, and their willingness to purchase foreign products does not appear to be affected by the HET. These findings extend the results presented by Story and Godwin (2023), who identified that consumers base their purchasing decisions more on the country to which the brand belongs than on the country of origin.

The study confirms that most Latin American consumers have low ethnocentrism levels, influencing their intentions to purchase foreign products. Although Latinos value the culture of their country of origin and identify with their roots, they prefer foreign products. This finding expands previous research, indicating that consumers in developing countries tend to possess low levels of ethnocentrism, making them more receptive to brands from developed countries than domestic ones (Kandogan, 2020; Shoham et al., 2017). Consequently, consumers may feel a disconnection from typical consumers, their behaviors, and the consumer culture of the dominant group, which can be attributed to various factors such as perceived social status, cultural influence, or personal preferences. This disconnection influences their willingness to buy and leads them to view products from their countries as lower quality.

Notably, the study's findings reassure market potential in Latin America. The low levels of ethnocentrism in Latino consumers and their preference for foreign products do not generate feelings of guilt towards purchasing products associated with their country originally. This is in line with the high level of SET as a determinant of PIN, a finding that has been suggested by Chryssochoidis et al. (2007) and supported by recent research (e.g., Akbarov, 2022; Miguel et al., 2023). It implies that consumers readily accept foreign products and may even prefer them if they perceive more significant benefits from the brands.

On the other hand, the findings reveal that gender moderates the relationship between SET and PIN only for women. No statistically significant relationships were found between Hard Ethnocentrism (HET) and PIN, nor between SET and PIN in men. These results suggest that the gender of Latino consumers is relevant only when women exhibit low levels of ethnocentrism. Consistent with previous research (Durço et al., 2021; Muchandiona et al., 2021), this study confirms that women tend to show more significant ethnocentric tendencies.

Although women's ethnocentric tendencies influence their purchasing intentions, these levels are moderate, indicating that while they value products from their country of origin and experience intense feelings of patriotism and national belonging, they are not exclusively limited to local products. On the contrary, they show a marked preference for foreign products, influenced by the product type and brand.

The results for men indicate that gender does not determine their purchase intentions, aligning with previous research in emerging markets (Cazacu, 2006; Makanyeza & Du Toit, 2017). The study suggests that men may adopt less ethnocentric attitudes toward their country of origin. Furthermore, it was observed that, regardless of the level of ethnocentrism, their purchase intention is not linked to CET.

Additionally, the study reveals no significant differences in men regarding their ethnocentrism and purchase intentions. Their purchasing behavior is consistent both when they exhibit low levels of ethnocentrism and when they are high. Therefore, CET does not appear to influence PIN in Latino men, suggesting they are willing to purchase domestic and foreign brands in their country of origin or other countries of residence. This study confirms that for Latino men, the preference for domestic or foreign products does not significantly influence their purchasing behavior, thus challenging the trend observed in various cultures of preferring domestic products (Wenbo & Lee Yeoung, 2022).

6Implications6.1Theoretical implicationsThis study's findings hold significant academic implications, notably expanding the literature on consumer behavior in emerging markets. By addressing a gap in understanding ethnocentric trends and their impact on purchase intentions, principally in developing countries like Latin America, this study makes a novel contribution that offers a fresh perspective on consumer behavior in these markets.

Further, the dimensions of CET, such as HET and SET, have yet to be fully conceptualized in the literature. This study has successfully conceptualized and operationalized these dimensions, providing a framework for future researchers. The operationalization of CET among Latino consumers deepens the understanding of their consumption behavior. The findings enhance understanding of the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and purchase intention within their country of origin.

The study reinforces the relevance of the TPB by demonstrating that SET significantly influences PIN. Moreover, PIN is predominantly shaped by ATT and PRV, which are found to exert more significant influence than SBJ, particularly within the Latin American context. This observation aligns with the tendency for decision-making in the region to be more autonomous, with weaker social pressures, especially about CET. ATT captures consumers' positive or negative evaluations toward specific actions, shaping their motivational predisposition.

Additionally, TPB not only influences behavioral intentions by addressing the perception of behavioral feasibility but also directly impacts actual behavior, particularly in contexts marked by significant external barriers. This theoretical insight shows the importance of developing more robust methodologies for measuring ATT and PRV in cultural research, as these factors provide a better understanding of decision-making dynamics. Furthermore, the findings suggest that interventions aimed at fostering desired behaviors should prioritize enhancing positive attitudes and reducing perceived difficulties over modifying social norms, especially in environments where such norms have minimal influence.

Although the TPB has been widely used to understand behavioral adoption across various disciplines, it has yet to be applied to examine the impact of SET and HET on the consumption behaviors of non-emigrant populations who remain in their country of origin. This study advances the current understanding of TPB by providing a theoretical explanation for the effects of consumer ethnocentrism on the consumption practices of Latinos.

The insignificance of HET in influencing PIN between native Latin American consumers suggests that, while there may be some loyalty or preference for local products, these sentiments do not necessarily drive purchasing decisions. Instead, consumers in this context may prioritize factors such as price, quality, availability, or the prestige associated with foreign brands over a strong sense of obligation to support national products.

This finding highlights a shift in Latin American markets, where purchasing decisions are guided less by rigid economic or cultural protectionism ideals and more by pragmatic, functional considerations. It also reflects integrating a more globalized consumer identity, characterized by an openness to foreign products, particularly when these better align with consumer expectations and needs.

Another significant academic contribution of this study is the examination of gender as a moderating factor in the association between CET and PIN. The study demonstrates that exposure to one's own culture and interaction with other Latino individuals can influence consumption styles and practices, potentially leading to the consumption of foreign goods. The findings support the influence of CET dimensions on Latino consumption patterns.

6.2Managerial implicationsThe study presents managerial implications relevant to business decision-making in Latin America. Marketing managers are advised to consider developing specific brands for this market. It is crucial to recognize that although levels of ethnocentrism are low in Latino consumers in their home countries, a sense of patriotism/nationalism can combine with local cultural identity and global trends; thus, the companies can capitalize on this by developing products and brands that incorporate traditional Latin American elements into the products while staying on top of global fashion trends, resulting in greater consumer acceptance.

The research highlights the importance of understanding variations within the Latin American market in attitudes toward foreign products. Companies can use this information to segment consumers more precisely based on their ethnocentrism level and adapt their marketing strategies accordingly. Furthermore, since Latin American consumers are willing to buy foreign products, companies can seize this opportunity in advertising. By highlighting the multiculturalism and diversity of options available in the market, companies can create an emotional connection with consumers, inspiring them to feel part of a global community and increasing the relevance of the products.

Companies must adopt a culturally sensitive approach that recognizes gender differences and respects the diversity of consumers' values, beliefs, and preferences in the region. Specifically, it is essential to adapt promotional messages and tactics to address the different perceptions and behaviors of Latin American men and women. Marketers should pay particular attention to consumer demographics when planning marketing programs in developing countries like those studied in this research. To optimize entry into foreign markets with ethnocentric consumers, marketers should prioritize establishing manufacturing facilities within those countries, engaging in joint ventures, and hiring local employees over traditional exporting strategies. Incorporating these in-country initiatives into local marketing messages can foster favorable attitudes and increase the acceptance of products.

On the other hand, given that women with low ethnocentrism exhibit a significant relationship between their ATT and PRV, marketing campaigns should strategically focus on this segment. Campaign messages should emphasize product attributes that enhance perceptions of utility, quality, and innovation while avoiding excessive emphasis on the product's origin. Employing narratives that emotionally resonate with consumers' aspirations—leveraging storytelling techniques and culturally relevant values—can be particularly effective in engaging this audience.

For male consumers, the lack of a significant relationship between CET and PIN suggests that marketing strategies should concentrate on universal factors. These include emphasizing the price, functionality, and convenience of the product. Communication targeted at men can forgo emotional or cultural references, instead prioritizing a straightforward presentation of tangible product benefits.

The region's low levels of CET present an opportunity to promote foreign brands effectively. These brands can be positioned by highlighting global attributes or aligning with international trends, such as innovation, fashion, or sustainability. Co-branding strategies that unite local and international brands could further enhance the acceptance of foreign products by tapping into Latin American consumers' openness to global influences.

Marketing managers must craft persuasive messages by the TPB. This addresses two critical aspects: (1) fostering positive attitudes toward purchasing by emphasizing personal benefits and (2) removing perceived barriers like price or access—particularly for female consumers. Moreover, continuous research is essential to uncover additional contextual factors, such as socioeconomic status or geographic location, that might affect PIN. Marketing managers should also closely monitor the effectiveness of their strategies by measuring key indicators, including the conversion of intentions into actual purchases and the return on investment (ROI) in targeted campaigns. By implementing these measures, businesses can effectively leverage gender and ethnocentrism dynamics to design marketing strategies that maximize market impact.

7Limitations and Recommendations for Future ResearchThe study presents some limitations that require consideration. First, no category of products or brands is specified to understand how levels of ethnocentrism influence purchase intentions. It would be beneficial to explore different product categories to determine whether consumer ethnocentrism is widespread or directed toward specific types of brands or products.

Second, snowball sampling was used, which was recommended for multicultural studies, although only 3% of respondents came from Central America, compared to 97% from South America. This result could generate a bias towards South American countries that it studies here, affecting the generalizability of the results. It is recommended to expand the sample to other Latin American countries, mainly Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean, to validate the findings, including longitudinal studies that examine the flexibility of ethnocentric behavior over time, evaluate the influence of external factors, and consider the multiculturalism of these emerging markets. Additionally, the potential biases introduced by the chosen sampling method may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations.

Third, it is important to acknowledge that external economic factors—such as global economic fluctuations or trade policy changes—could significantly influence consumer behavior and ethnocentrism. These factors may also affect the stability of the observed trends over time, introducing variability that could impact the study's results. This consideration opens avenues for future research to explore how such external factors shape ethnocentrism and its implications for consumer behavior, particularly in emerging markets.

Finally, given that movements related to gender discrimination in Latin America are not as advanced as in developed countries, the study addressed two gender categories: masculine and feminine. Latin America still needs to be updated in this regard. Without a doubt, the analysis could be much more precise if the demographic data on gender could be segmented into more than two categories and included other variables, such as acculturation, social culture, and materialism, to understand better Latin consumer purchasing motivations and how developed economies in the region can differentially impact different countries and populations.

Despite these limitations, this study's findings contribute to the dearth of market research regarding native Latino consumers. This study significantly enriches the literature on consumer behavior in Latin America and provides a valuable foundation for future research in this area.

8ConclusionThe research uncovers a significant shift in Latin American consumers' ethnocentrism towards their country of origin. The findings have a direct impact on consumer behavior, given that they present a gender difference. The results challenge the conventional belief that ethnocentrism acts as a barrier to imported goods, as consumers prefer domestic and foreign products. The multiculturalism of these markets has led to changes in their attitudes and consumption patterns. Despite economic, cultural, and geographical variations, native Latin American consumers maintain a solid connection to their national identity. The study underscores the enduring influence of cultural factors on consumer behavior, even in the face of globalization and multiculturalism.

The impact of CET and PIN to maximize marketing strategies must adopt gender-sensitive approaches that account for differences in consumer behavior. Unlike men's, women's PINs are influenced by their level of ethnocentrism. For women with SET, campaigns should highlight product attributes such as utility, quality, and innovation while incorporating storytelling and culturally relevant themes to deepen engagement. Avoiding an excessive focus on product origin is crucial to maintaining their interest. Conversely, marketing strategies targeting men should prioritize practical factors such as price, functionality, and convenience, avoiding emotional or cultural appeals. The region's low ethnocentrism allows foreign brands to emphasize global attributes like innovation and sustainability with co-branding strategies. Guided by the TPB, marketers should design campaigns that cultivate positive attitudes and address perceived barriers, explicitly focusing on endorsements that resonate with women.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIliana E. Aguilar-Rodríguez: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Leopoldo G. Arias-Bolzmann: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Carlos H. Artieda-Cajilema: Investigation, Data curation. Carlos Artieda-Acosta: Writing – review & editing. Ana-Belén Tulcanaza-Prieto: Writing – review & editing.