In this paper we argue that there is an extensive number of studies examining how firms obtain new products from their interactions with scientific agents, but other type of benefits has been overlooked. Specifically, we add to previous literature by considering not only product innovation, but also exploratory (long-term) and exploitative (short-term) results. We administer a tailored survey to firms collaborating with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and data was completed with secondary sources. Results based on a sample of 756 firms suggest that firms consider all types of result as moderately important to them. Moreover, we observe that small firms report higher benefits in terms of product innovation and long-term results in contrast to large firms.

The academic literature emphasizes that innovation is a distributed and interactive process among a number of economic actors rather than constrained to an individual firm domain (Brunswicker, 2014; Chesbrough, 2003). Among the wide variety of agents with which firms can relate, universities and public research centers, hereafter public research organizations (PRO), have taken pride to be considered as main partners, and scientific research has come to be conceived as one of the engines of industrial innovation (Henderson, Jaffe, & Trajtenberg, 1998; Mansfield, 1998). Based on this argument, many governments worldwide have launched important initiatives to encourage greater interaction between firms and PROs (Cosh & Hughes, 2010; DIUS, 2008; OECD, 2003) and the analysis of this kind of interaction has become an outstanding topic of interest for academics and policy makers. As a product, in the last decades a large body of literature has emerged related to the drivers, channels and benefits derived from this type of interactions (Núñez-Sánchez et al., 2012; Freitas & Verspagen, 2017; Olmos-Peñuela, García-Granero, Castro-Martínez, & DEste, 2017).

From the perspective of firms, many scholars have stated that PROs may act as an important source of complementary skills and resources with a large potential for learning (Un, Cuervo-Cazurra, & Asakawa, 2010). Thus, while the interaction with agents within the supply-chain enables a firm to deepen existing technological capabilities, drawing knowledge from research agents provides a firm with the opportunity to explore new technological areas and helps to broaden its technological knowledge base (Faems, Van Looy, & Debackere, 2005). However, PROs do not limit themselves to exploratory solutions, existing studies provide evidence of these institutions providing more operational or short-term solutions (Faems et al., 2005; Santoro & Chakrabarti, 2002). In this line, Arza (2010), for instance, stated that PROs might be used by firms to strengthen production capabilities via quality control, technical services and problem solving.

This stream of literature informs about the heterogeneity of the benefits firms derive from interactions with PROs. However, to date few studies consider the wide range of benefits that have been highlighted in the literature and focus on one main result related to the development of new products (e.g. Monjon and Waelbroeck, 2003; Belderbos, Carree, & Lokshin, 2004; Lööf and Broström, 2008; Belderbos, Carree, Lokshin, & Sastre, 2015; Guzzini & Iacobucci, 2017; Robin & Schubert, 2013; Vega-Jurado, Gutiérrez-Gracia, & Fernández-de-Lucio, 2009). This is explained because most of these studies are based on the analysis of secondary sources, that is Community Innovation Survey (CIS) data, and few efforts have been made to generate primary data and identify results beyond product innovation (to the exception of Bishop, D'Este, & Neely, 2011; Dutrénit, De Fuentes, & Torres, 2010; Fuentes & Dutrénit, 2012). To solve this limitation in this study we use primary data and analyze how firms can obtain not only new products from PRO interactions but also other short and long-term benefits.

In addition, recent studies call for more research on the type of firms that benefit from PRO-I interaction (Barge-Gil, 2010). Along these lines, Bishop et al. (2011) suggest that results from firm's interactions with universities are contingent on factors such as firm's R&D commitments, geographical proximity of university partners and firms, and research quality of universities. In a similar way, Dutrénit et al. (2010) carried out an analysis on the Mexican case and proposed that depending on the channels of interaction used in PRO-I interaction, the benefits perceived by firms differ in terms of short-term activities and long-term strategies. Fuentes and Dutrénit (2012) identified a set of benefits and found that these benefits are mainly influenced by the type of channel used to coordinate the interaction. Among the factors influencing the outputs from PRO-I interaction mentioned in these studies, the impact of firm´s size on the different types of benefits have been overlooked.

Following this line of inquiry, in this paper we explore the range of potential benefits that firms obtain from interactions with PROs in order to understand why the effect of PROs in firms could be underestimated by only considering innovation results. We also aim to extend the determining factors. In particular, we are interested in including factors beyond R&D, by looking thoroughly at firm´s size as a determining factor of their attitude towards exploitation of external knowledge. This analysis is relevant taking into account that the promotion of PRO-I interactions occupies a central place in innovation policies and that, at least in the Spanish case, the design of these policies rarely recognizes the wide range of benefits associated to these interactions and their drivers. Also, PRO-I interaction policies should consider with special attention the impact of PROs on small and medium firms since they constitute the larger part of Spanish firms. Moreover, the study of PROs impact on firms, has been noted as being especially relevant in national systems of innovation where PRO-I interactions have been less frequent and weaker, such as the Spanish case (Dutrénit et al., 2010; Lorentzen, 2009; Vega-Jurado et al., 2009).

This study is based on an original data set collected through a survey applied to a sample of Spanish firms that have established a formal interaction with the Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), the most important PRO in Spain. The selection of the sample is relevant since the fact of choosing firms collaborating with CSIC means that we can actually measure the impact of that collaboration.

The remainder of this paper is structured into five sections. The second section reviews different bodies of literature that addresses the issues discussed here. Section 3 describes the strategy for data gathering and the construct of variables. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 concludes and presents the paper's implications.

2Theoretical framework2.1PRO-I interaction results: Beyond product innovationProduct innovation is not the only way in which firms may gain from their interactions with PROs. Several studies suggest that firms can benefit from the interaction with scientific partners in other ways (Bierly, Damanpour, & Santoro, 2009; Cohen, Nelson, & Walsh, 2002; Corolleur, Carrere, & Mangematin, 2004; Murray, 2004). Actually, PROs are broader repositories of knowledge, information, skills, and infrastructures, among other factors, which are potentially transferable to firms (Amara and Landry, 2005; Becheikh et al., 2006).

Researchers have pointed out that firms’ interactions with PROs may contribute to increase in-house technological and scientific capabilities that are distant from the firm's existent knowledge base (Santoro & Chakrabarti, 2002), inasmuch as to generate new human resources that would have been difficult to obtain without such interactions (Feller, Ailes, & Roessner, 2002). This last result is usually more distant from the direct application of the knowledge acquired and emphasizes the development of broader capabilities, such as the generation of a high qualified workforce and internal research capabilities. Many times, the interaction between firms and PROs gives opportunity for experimentation with complex and risky activities and provides opportunities for bi-directional learning (Miotti & Sachwald, 2003; Un et al., 2010). Thus, PRO-I interaction can bring not only product innovations to firms but also long-term benefits related to increasing the firm's ability to absorb technological information, access complementary research and exploring new technological alternatives.

Likewise, due to PRO interaction, firms achieve to reduce the risks and costs associated with R&D activities and obtain consulting advice to solve production problems (Belderbos et al., 2004; Miotti & Sachwald, 2003). Interactions between PROs and company personnel may also aid in the access of resources to perform tests, quality control, and training programs (Arza, 2010). Thus, the interaction between firms and PROs allows firms to obtain economic solutions to operational problems.

The benefits mentioned above have been grouped in different ways. For instance, Dutrénit et al. (2010) distinguishes between two types of result other than the traditional product innovation: First, results related to how firms, as a consequence of their interaction with PROs, may nurture their absorptive capacity and increase their ability to become innovative in the long-term. Second, results related to how firms may benefit more directly and in the short-term by obtaining consulting advice from the PRO to solve production problems or by using laboratory resources. Along these lines, Bishop et al. (2011) distinguishes between exploratory (long-term) and exploitative (short-term) benefits. As in the case of Dutrénit et al. (2010), exploratory results are linked to the firm's capability of becoming innovative in the long-term and is associated with experimentation, flexibility, divergent thinking, risk-taking, variance increase, new knowledge and new technology uses. Exploitative results are related to the firm's capability of benefiting in the short-term through for instance, problem solving efficiency, control, certainty, reduction of variance, knowledge improvement, and existing technological improvement (Chams-Anturi, Moreno-Luzon, & Escorcia-Caballero, 2019).

Independently of the criteria used, what this literature points out is that the benefits from PRO-I interactions are multiple and not only related to the development of new or improved products. This idea is particularly relevant in order to analyze the impact of PRO-Industry interactions in national systems of innovation where these kinds of relationships have been weaker and less effective as strategies to promote innovation results, such as the Spanish case (Vega-Jurado et al., 2009). Along these lines, previous research indicates that in peripheral regions, universities and research organizations tend to be used more for the supply of support services and as partners to access more routine problem-solving services and consultancy than for the development of R&D and innovation projects (Pinto et al., 2015).

2.2The role of firm´s size in benefiting from PRO-I interactionAmong the empirical research on PRO-Industry collaborations, firm´s size has been usually treated as a determinant factor of cooperation but less attention has been paid to the effect of this variable on the impact of such collaborations. Though we acknowledge that the relationship between interaction and size is highly complex (Johnson, Webber, & Thomas, 2007), further research is necessary to determine whether firms’ structural characteristics enable companies to differently benefit from interacting with external partners (Huizingh, 2011). Even though studies suggest that most open innovation adopters are large firms (Bianchi, Cavaliere, Chiaroni, Frattini, & Chiesa, 2011; Keupp & Gassman, 2009), smaller companies also practice open innovation extensively and this is becoming more frequent in the last years (Hervás-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, Boronat-Moll, & Estelles-Miguel, 2019; Pittz, Intindola, Adler, Rogers, & Gard, 2019; Van de Vrande, De Jong, Vanhaverbeke, & De Rochemont, 2009; Xia & Roper, 2016).

Regarding firm´s size there are logical arguments to the existence of the greater (lesser) benefits and lower (higher) costs of interactions with scientific agents. On the one hand, the literature argues that cooperation is easier for large firms because they have abundant resources (e.g. information services, human resources, technical infrastructure) that complement PROs knowledge and ease the management of collaboration agreements (Tether, 2002; Veugelers, 1998; Vivas-Augier & Barge-Gil, 2015). These arguments are in line with the resource-based view (RBV) (Dierickx & Cool, 1989), which stresses that firms use external knowledge sources in order to leverage their superior resources via the complementary assets possessed by other firms or institutions (Teece, 1986). Thus, firms with high levels of internal resources will tend to favor external collaboration due to their greater ability to appreciate and internalize valuable external knowledge. Eventually, large firms are in a better position to create and maintain large networks when interacting with PROs.

However, on the other hand, the resource dependence theory (Finkelstein, 1997) offers an alternative argument based on the internal resource scarcity. According to this view some firms are not able to generate all the resources they require; therefore, they must look for alternative ways to overcome this weakness. In this view, external collaboration is seen as a way to acquire the resources that firms lack but which are necessary for firm survival (Dias & Magriço, 2011). Following this line of reasoning, small firms, because of this liability of resources, are more incentivized not only to collaborate with PROs but also to use this collaboration as a relevant strategy to improve their performance (Mazzanti, Montresor, & Pini, 2009; Van de Vrande et al., 2009). This effect is referred to as the ‘need effect’: firms with limited internal capabilities are more motivated to access external resources (Barge Gil, 2010a,2010b;Shaver & Flyer, 2000).

As can be observed, arguments can be found to support opposing views regarding the effect of the firm´s size on perceived benefits from interactions with PROs. In this paper, we argue that one way to make some strides towards a resolution of these controversies revealed by the literature is analysing different types of benefits coming from such interactions.

Taking as starting point the “need effect” argument we argue that in the case of firms that already collaborate with PROs, smallness will play a relevant role in benefiting from PRO-I interaction. This is especially relevant when firms seek to achieve product innovations or long-term benefits related to the strengthening of internal capabilities. Due to their lack of internal resources small firms have a greater need to access external scientific and technological knowledge to carry out innovation activities. In this sense, when smaller firms collaborate to PROs, they use external knowledge strategically because they do not have the critical mass to be able to cope on their own with the uncertainty and complexity of innovation projects. Thus, collaboration with PROs represents to SMEs a more important strategy to achieve innovation results or strength internal capacities compared to large firms. Barge Gil (2010, b), for instance, pointed out that although size strongly and positively influences the firm's decision about whether or not to cooperate to innovate, small firms use cooperation as their main strategy to obtain new products. In other words, large firms tend to cooperate more with external agents, but small firms benefit more from cooperation as a strategy to develop new products compared to large firms. Narula (2004) also argues that when small firms succeed in collaborating with PROs, they need to overcome less organisational and bureaucratic rigidities in contrast to large firms. Thus, when they manage to collaborate, small firms are accustomed to innovate with an external focus and they benefit from their flexibility (Lee, Park, Yoon, & Park, 2010; Siegel, Waldman, & Link, 2003). Based on these arguments our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1. SMEs are more likely than large firms to achieve product innovations as a result of collaborations with research organizations.

Another set of potential benefits coming from interactions with PROs refers to the learning opportunities in the long-term and the strengthening of R&D internal capacities. However, SMEs and large firms could achieve these long-term benefits differently. First, because SMEs have fewer resources and abilities to develop new knowledge internally than large firms, they rely more extensively on their collaborations with PROs to explore new areas and absorb new knowledge (Lee et al., 2010). By contrast, large firms can use their financial and human resources to develop new knowledge internally more easily and depend less on external collaborations to enhance their innovation capacities (Grigoriou & Rothaermel, 2017). Thus, since SMEs´ resources and technological capabilities are limited (Huizingh, 2011), PROs may provide them with these complementary assets that otherwise would have been difficult for them to acquire individually. Chiambaretto, Bengtsson, Fernández, and Näsholm (2020), for instance, found that small firms value the collaboration with competitors that provide significant learning opportunities more than large firms. Second, because small and medium-sized firms enjoy behavioral advantages, such as flexibility and rapid response, they are better positioned to introduce changes in their organisational structure in order to benefit from opportunities in the environment and to learn from external agents how to generate a favourable climate and reinforce internal capabilities (Rogers, 2004). Along these lines, Olmos-Peñuela et al. (2017) found that thorough collaboration with PROs, SMEs can access valuable resources and strengthen their innovation culture in the long-term. Therefore, while we acknowledge that both SMEs and large firms could benefit from the learning opportunities provided by PROs, we suggest that small firms will value these long-term benefits more than large firms, which can rely more on their own resources to develop the capabilities necessary to sustain their growth. We thus establish the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. SMEs are more likely than large firms to achieve long-term benefits as a result of collaborations with research organizations.

Finally, firms may also benefit from their interactions with PROs in the short-term by reducing cost of innovation activities or by obtaining consulting advice to solve production problems. Collaboration improves the efficiency of resource utilization (Garrette, Castañer, & Dussauge, 2009), allowing firms to realize economies of scale, access to scientific facilities, and reduce research and development costs. Although these benefits are important for both SMEs and large firms as R&D costs have increased significantly over the years, we argue that large firms could be in a better position to achieve this kind of result than SMEs. Large firms, as it has been mentioned, have greater resources and complementary capacities, compared to SMEs, which ease the search for partners and the management of collaboration agreements. In this sense, when looking for collaborations, large firms are better positioned to specify what type of expertise or technical service they require from external partners as well as to focus more on their internal core capabilities and exploit economies of scale (Chiambaretto et al., 2020). In this sense, large firms, compared to SMEs, can manage the relationships with PROs more efficiently in order to achieve specific results in the short-term. According to these ideas, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: SMEs are less likely than large firms to achieve short-term benefits as a result of collaborations with research organizations.

In this study, we focus on Spanish firms because Spain according to the Innovation Union Scoreboard classification is within the moderate innovator group, that is below the European Union average (European Commission, 2014). If we compare to the rest of the world, Spain is ranked 27th in terms of innovation (Dutta, Lanvin, & Wunsch-Vincent, 2014). The OECD, pointed out that the Spanish national innovation system depends highly on public sector organisations and displays relatively low levels of firm's R&D expenditure (OECD, 2014).

3.2Data sourcesThe population under study is integrated by firms establishing some type of formal collaboration with the largest Spanish PRO, CSIC, during the period 1999–2010, which adds up to 5334 agreements signed by 1891 companies. In 2011, CSIC counted with 126 research institutes, which employed 14,050 employees (CSIC, 2012). Together with Spanish universities and other institutions, CSIC plays a relevant role in contributing to scientific and technological progress. The institution generates 20% of the Spanish scientific production and is the leading organization in generating public and private contracts, registering patents and technology licencing in the country (Olmos-Peñuela et al., 2017).

From the 1891 companies, 794 firms agreed to participate by completing the survey. We conducted a pre-test of the questionnaire to assure understandable questions, and between 1 October 2010 and 31 January 2011 a questionnaire was sent to these companies, specifically to the R&D managers, technical managers or similar. The survey was administered face to face. To test for the existence of common method bias in our data we performed a Harman's one-factor test; the results suggested that our data did not suffer from this problem (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

The survey asked general questions on the firm's characteristics and their innovation activities. Also, the survey contained specific questions in relation to the firm's collaboration with CSIC during the period mentioned, including the outcomes obtained as a product of such partnership. Information not fully available by the questionnaire such as the sector, firm's age and firm's size, was accessed through the Iberian balance sheet analysis system (SABI) dataset. We analysed only the firms that presented information in both datasets, resulting in a final sample of 756 firms.

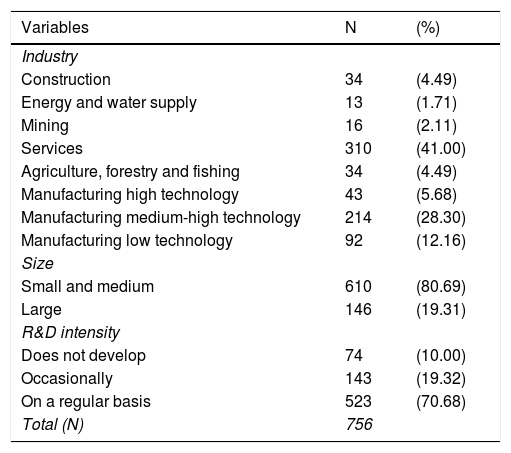

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of our sample, in terms of industry, size and R&D intensity. The sample's industry composition is similar to the Spanish industry, though figures in our sample show that the manufacturing sector is overrepresented and services sector is underrepresented (INE, 2012). The majority of firms in the sample are SMEs around 80.69%, and approximately 90% are pursuing R&D activities, which corroborates that firms collaborating with scientific agents are often intensive in R&D. Moreover, 89% of large firms pursue R&D activities in a continuous basis, while the percentages for small and medium firms is of 66.28%. These figures are relatively similar to those of National Innovation Surveys were firms that collaborate with PROs have larger R&D departments, employ skilled human resources and perform R&D activities in a continuous basis (Fuentes and Dutrénit, 2010).

Sample distribution.

Note: Internal R&D does not add to N = 756 because of missing values.

We use three dependent variables which capture the different benefits perceived by firms from interactions with PROs. To build these variables we asked the group of firms to evaluate the importance of achieving different outcomes from their interaction with CSIC.

One of the outcomes considered was if as a consequence of the interaction with CSIC, the firm introduced a new product or service into the market. The answer to this question was used to measure the variable product innovation on a scale ranging from 1 (benefit is non-existent or not important) to 4 (benefits are considered as very important).

The other outcomes were grouped into two categories referred to as long term and short-term benefits drawing on the concepts proposed by Dutrenit et al., (2010). The first group is based on the idea that firms may benefit from PROs by nurturing their ability to become innovative in the long-term by, for instance, strengthening their R&D departments or improving their technological capabilities. The second group is based on the argument that firms may benefit from PROs more directly by obtaining consulting advice or assistance in problem resolution. Following this reasoning, long-term benefit measures if the firm, due to the interaction with CSIC, has created a new R&D department, has increased R&D investment or has hired new personnel. We ask respondents to evaluate the benefit attributed to these different results when interacting with CSIC in a scale ranging from 1 (benefit is non-existent or not important) to 4 (benefits are considered as very important). Since we have three items we calculate the average, which shows acceptable reliability (Cronbach's alpha equals 0.70), and we recategorize the variable into an ordinal one: if the value of the variable was between 1 and 1.4, the converted variable took value 1; if the value of the variable ranged between 1.5 and 2.4, the converted variable took value 2; if the value of the variable was between 2.5 and 3.4, the converted variable took value 3; and if the value of the variable ranged between 3.5 and 4 the converted variable took value 4. On the other hand, short-term benefit is built as the average of the following items measured in the scale 1 (benefit is non-existent or not important) to 4 (benefits are considered as very important): obtain assistance in problem resolution, obtain consulting advice, acquire scientific and technical resources, and reduce the risk and costs associated to R&D, which shows acceptable reliability (Cronbach's alpha equals 0.63). We also convert the variable to ordinal as in the previous case: if the value of the variable was between 1 and 1.4, the converted variable took value 1; if the value of the variable ranged between 1.5 and 2.4, the converted variable took value 2; if the value of the variable was between 2.5 and 3.4, the converted variable took value 3; and if the value of the variable ranged between 3.5 and 4 the converted variable took value 4. The recategorization of the mentioned variables from continuous to ordinal is necessary to homogenize the scale of measurement to our first dependent variable product innovation.

3.4Independent and control variablesOur main independent variable is related to the size of the firm. To measure this characteristic, we created a binary variable to distinguish between SMEs and large firms. This variable –SME- takes value one in the case that the number of employees is less than 250, and takes value 0 otherwise.

We control for specificities related to the collaboration of the firms with CSIC. First, we generate six binary variables that measure distinct channels the firm has used to interact with CSIC, which are, Joint research, contract research, services, training, diffusion and non-formalized channel (Dutrénit et al., 2010; Perkmann & Walsh, 2007). Joint research represents whether the project was part of a public program financed by the Spanish national research plan, other regional programs or EU programs. Contract research measures whether the research was contracted out to CSIC. Services measures if the firm has been involved in consultancy activities and whether the firm has used CSIC's installations and equipment. Training captures whether the firm has allowed employees to pursue training stays at CSIC or specialized training with CSIC's researchers. Diffusion measures if there has been joint participation in dissemination activities. Lastly, Non-formalized stands for non-formalized enquiries or collaborations that have been established between the partners without being channelled through the institution (Olmos-Peñuela, Molas-Gallart, & Castro-Martínez, 2014). The existing literature provides enough evidence to assume that the benefits from PRO-I are contingent on the channel used to coordinate the relationship.Vega-Jurado, Kask, and Manjarrés-Henríquez (2017)found a distinction between the degree of novelty of innovation product resulting from R&D contracting and joint research with universities, whileDutrénit et al. (2010)found that research, human mobility, and consultancy bring production and innovation benefits for Mexican firms. In this paper, we control for this factor but we do not state a formal expectation about it. Second, we capture previous experience in collaborations through a binary variable that takes the value 1 if the firm indicates that CSIC is its most frequent external collaboration partner and 0 otherwise.

We also control for firm's characteristics, that is, firm's R&D intensity, firm's age and firm's industrial sector. We measure R&D intensity in a scale ranging from 1 to 3, where 1 means that the firm does not develop internal R&D, 2 measures if the firm occasionally pursues R&D and 3 captures whether the firm develops internal R&D on a yearly basis. Firm age is measured as the number of years since the firm's founding until 2011.We control for firm's industrial sector by following the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE): Construction, Energy and water supply, Mining, Services, Agriculture, Forestry and fishing, High technology manufacturing, Low technology manufacturing and Medium-high technology manufacturing.

3.5Empirical strategyTo understand the multiple outcomes obtained through the interaction with CSIC we use ordered probit regression analyses, where the dependent variables product innovation, short and long-term benefits take values from 1 to 4.

Attention should be paid to the tight connections between the potential results derived from firms and PROs’ collaborations, that is, between the benefits realted to long-term and short-term results. For instance, the establishment of linkages with PROs with the objective of specific problem solving (short-term benefits) could be tightly connected with the ultimate strategy of introducing new products into the market (product innovation). Also, the search for strengthening internal R&D department (long-term benefits) can be intimately related to firm's ultimate development of products (Putnam, 2001; Tether & Tajar, 2008). The non-independency of the different results could generate estimation problems due to cross-correlations. Seemengly unrelated regressions models account for dependency between the explained variables and potential correlations in the error terms.

4Analyses and resultsTable 2 reports the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the variables in our study. Descriptive figures inform that firms report a moderate usefulness of these collaborations, especially in the case of long-term benefits. All three dependent variables present mean values around 2 indicating that respondents perceive the results obtained from PRO-I interaction as little important. These figures chime with empirical results pursued in the Spanish context showing that firms do not assess interactions with scientific agents as extensively valuable (Vega-Jurado et al., 2009). Similar cases have been observed in other comparable national systems of innovation, such as Mexico (Dutrénit et al., 2010). These countries are characterised by weak PRO-I interactions where research organisations and firms are technological distant and there are important barriers for knowledge transfer.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Note: Sector dummies not included in descriptive statistics.

* p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01.

In our entire sample, 80% of the firms had fewer than 250 employees and were classified as SMEs, while the remaining firms (20%) were categorized as large firms. Table 2 also shows the average of firms that have used different channels to coordinate the relationship. Services is the most used channel (76%) followed by contract research (56%) and joint research (47%). It is important to note that non-formalized inquiries have been used by 51% of the firms, which implies that half of the firms have established an informal collaboration besides some type of formal collaboration with CSIC. Thus, ignoring informal links could be too narrow an approach to provide a comprehensive perspective on collaboration processes (Olmos-Peñuela et al., 2004).

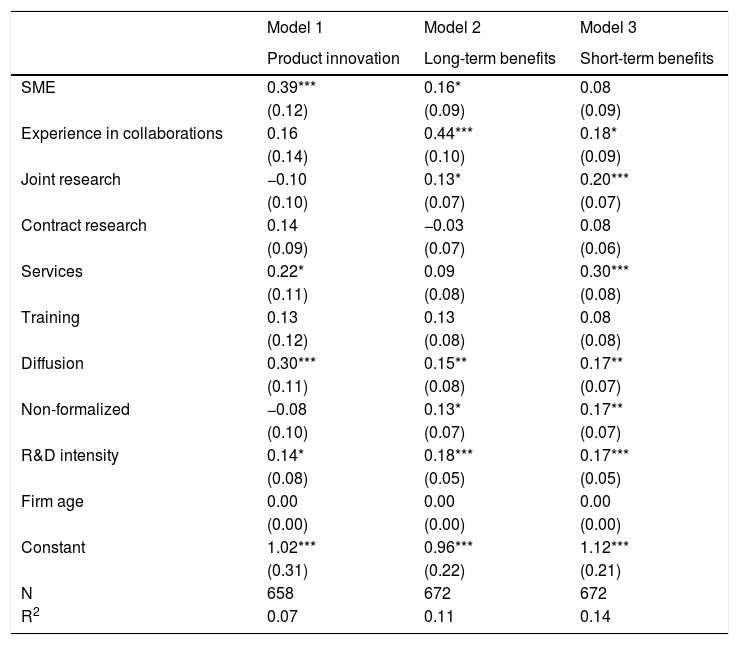

Low correlations shown in Table 2 inform us that multicollinearity is not a problem in our data. To analyze the associations between the variables in our study we use ordered regression analyses. Table 3 shows the three different regressions for each one of our dependent variables: product innovation, short-term benefits and long-term benefits. The highest VIF is of 5.87 and the overall highest mean VIF is of 1.91, values that are well below the recommended value of 10, which proofs no multicollinearity problems (Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Wasserman, 1996). All three models in the table include control variables and the main independent variables.

Ordered probit regression analysis. Large firm as reference category.

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Industry dummies included in the regression.

* p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01.

Regarding the main variables of the study, results in model 1 show that the variable SMEs (versus large firm) is positively related to product innovation as a result of collaborating with CSIC (β=0.41, p<0.01). Model 2 shows a positive association between SMEs (versus large firm) and obtaining long-term benefits (β=0.26, p<0.05). Therefore, hypothesis 1 and 2 are supported. Contrastingly, in model 3 the coefficient of SMEs on short-term benefits is not significant. Thus, hypothesis 3, which suggests that larger firms benefit more than smaller firms from short-term results is not supported. This result seems to suggest that both, SMEs and large firms, could equally perceived short-term benefits from their interactions with PROs. We pursue robustness checks in order to account for possible interdependencies between the different dependent variables and results did not change (see Table 4).

Seemingly unrelated regressions model. Large firm as reference category.

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Industry dummies included in the regression.

* p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01.

For further validity of our analyses we perform a post-estimation analysis to validate whether coefficients are similar or different. Results provide strong evidence against the proportionality of coefficients. This indicates that there are significant differences between coefficients: the effect of firm´s size on product innovation is greater than its effect on long-term benefits (p<0.10), and firm´s size has a stronger effect on product innovation than short-term benefits (p<0.05).1 This suggests that SMEs interact with PROs most of all to create new products.

Results in models 1, 2, and 3 show the following association effects regarding control variables: Diffusion is positively associated with all benefits analysed, whereas joint research and non-formalized agreements are positively associated with long-term and short-term benefits. Services are positively associated with product innovation and short-term benefits, whereas training and contract research is not relevant for any of the benefits. On the other hand, R&D intensity presents a positive association with the three benefits considered (product, short and long- term benefits), while the firm´s age is not significant.

5Discussion and conclusionsPrior research on PRO-I interactions has mainly focused on the analysis of determinants of such collaborations or their impact in terms of innovation outcomes. However, the issue of what firm´s characteristics determine the benefits that firms achieve as a result of these collaborations has been underestimated. In this sense, more generalized empirical evidence could bring new insights to existing debates. This paper has addressed this issue by using a tailored survey applied to a sample of Spanish firms that have established a formal interaction with the Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), the most important PRO in Spain. This paper considers that the benefits firms gain from PRO-I may go beyond innovation results and may be determined by the firm´s size.

From a sample of firms that collaborate with a public research organization, we observe that on average they have benefited scarcely from their interactions. It is relevant to understand that the setting of this study is integrated by Spanish firms, a country characterized by manifesting weak PRO-I interactions (Vega-Jurado et al., 2009). Figures also show that short-term benefits are proportionally given more importance than those benefits oriented towards long-term or even product innovation. This result is in line with other studies conducted in national innovation systems which are under-developed and show that in these contexts, the role of PROs is evolving from the generation of knowledge and the strengthening of human resource and research capabilities to a more operational focus in which problem-solving and contributing to specific challenges the firm face is strategic (Dutrénit et al., 2010; Vega-Jurado, Manjarrés-Henríquez, Fernández-de-Lucio, & Naranjo-Africano, 2020).

In the econometric analysis the trend we expected for SMEs is confirmed. We find that SMEs, compared to large firms, tend more to develop new products and achieve long-term benefits from their relationships with PROs. This empowers our argument that SMEs are in a greater need of resources in contrast to large firms and value more positively interactions that are aimed at strengthening their R&D capabilities, their human resources, and their capability of being prepared to absorb new knowledge and to adapt to changing environments.

However, the analysis did not confirm that large firms achieve more short-term benefits from their interactions with PROs compared to SMEs. Even though large firms are better situated to manage the collaboration agreements with scientific agents and clearly define their problems and requirements, the flexibility of smaller firms may ease the exploitation of external knowledge. Thus, large firms and SMEs can equally exploit the collaborations with scientific institutions as a strategy to obtain consulting advice or assistance in problem resolution. In fact, as has been mentioned, this type of benefit is the most usual in the sample.

The analysis also confirms the significance of firm´s R&D intensity as a determinant of the exploitation of external knowledge. In line with the “absorptive capacity” argument (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990) the benefit a firm can obtain from external agents is highly dependent on the firm's existing knowledge, which in turn is a by-product of its R&D efforts. Accordingly, firms with higher levels of internal R&D activity find collaboration with research organisations more relevant than firms with low internal R&D capabilities, which implies an essential complementarity between internal and external sources of knowledge. Likewise, prior collaborative experience with PRO appears as an important factor to exploit these interactions as a way to achieve both long and short-term benefits. Past experiences allow firms to institutionalize learning mechanisms that enable them to assimilate and apply scientific knowledge faster and more effectively. Besides, due to the bureaucratic and organizational barriers present in this type of relationship, prior experience is an important factor to facilitate communication between the partners and the management of the collaboration agreements.

If we put together the above results, one of the main implications that emerges is that still firms are not highly valuing the benefits from their collaborations with PROs. This is common in countries integrated by firms with low absorptive capacity and informs policymakers about the need of making these collaborations more successful. Moreover, in the context of designing innovation policies and the promotion of PRO-I collaborations policy makers should be considering the success of collaborations based on a wide range of factors, and not measured solely in terms of new products generated and introduced into the market. If this is not the case, much of the impact can be underestimated. Policy makers should also consider the degree in which the benefits of PRO-I interactions differ according to firm's characteristics, especially its size, R&D intensity and experience in previous collaboration.

Limitations of the study need to be mentioned. Data was collected at one moment in time, in such a way that problems related to endogeneity cannot be totally ruled out. The study is conducted on firms that have collaborated with the PRO, thus generally intensive in R&D, which reduces the generalization of our results to firms that did not collaborate. Third, we focused on the Spanish context but other national systems of innovation should be considered in order to conduct a more comprehensive analysis.

This work was supported by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) under the IMPACTO Project and by Colciencias through grant 121577657885. The authors thank Pablo D'Este for their useful comments and suggestions during the several stages of the research process and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Any errors or omissions remain the authors’ responsibility.