Push and pull driving factors are important motivational antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Perceptual variables, such as perceived risk in venture creation and opportunity recognition, also play a significant role in this question. However, the existing research has not analyzed all these factors in conjunction, which would enable better identification of entrepreneurial intention. This study advances the understanding of the relationship between push–pull factors and entrepreneurial intention through an analysis of the mediating effects of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. The results of a structural equation model (partial least squares, PLS) applied to a sample of 616 Spanish undergraduate students reveal that the influence of pull factors on entrepreneurial intention is positive, and partially mediated by opportunity recognition. However, the influence of push factors on entrepreneurial intention is indirect and negative. Push factors have a negative impact on entrepreneurial intention, increasing individuals’ perceptions of risk in venture creation and undermining their opportunity recognition. The paper extends the current knowledge on how entrepreneurial intention is formed, integrating the Push-Pull Theory into Krueger's 1993 Model of Entrepreneurial Intention, thus incorporating motivational and perceptual variables into a unified model. The results suggest practical implications for forming entrepreneurial intention in individuals from three perspectives: entrepreneurship education, public policy and practitioners. Specifically, these implications mainly focus on the importance of designing programs and policies aimed at favoring pull-related motivations (i.e., self-realization, independence), as well as helping develop perceptions that venture creation entails low risk and that an interesting high-value added business opportunity is recognized.

Entrepreneurship is a process (Zapkau, Schwens & Kabst, 2017) involving three related but distinct stages: (1) the development of entrepreneurial intention and/or commitment to becoming self-employed (Krueger, 1993), (2) time and resource investment in the gestation period of a project (Carter, Gartner & Reynolds, 1996), and (3) entrepreneurial behavior and outcome success (e.g., founding a legal entity, earning sales revenues for the first time; Kessler & Frank, 2009). While understanding the latter two stages can help entrepreneurs expedite venture creation and become successful, the first stage requires non-negligible attention (Barba-Sánchez, Mitre-Aranda & del Brío-González, 2022; Fayolle & Liñán, 2014), as it represents the entrepreneurial process just before the act of creating a new venture and seeks to understand why some individuals decide to start a venture while others do not (Baron, 2004). As such, paying attention to this stage and, therefore, to the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention, is key in designing effective policies that cultivate entrepreneurship (Puni, Anlesinya & Korsorku, 2018). In this regard, recent studies consider that the motivations to start a venture are critical antecedents of this intention (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Carsrud & Brännback, 2011; Miranda, Chamorro-Mera & Rubio, 2017). These works all draw on Push-Pull Theory (Amit & Muller, 1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010; Gilad & Levine, 1986; Kirkwood, 2009; Thurik, Carree, van Stel & Audretsch, 2008) to argue that push- or pull-related motivations explain how entrepreneurial intention is formed.

Despite their differences, both push and pull factors can be reasons for pursuing self-employment (Dawson & Henley, 2012; van der Zwan, Thurik, Verheul & Hessels, 2016). Pull factors are the motivators that “attract” individuals to create a new venture through their own personal desire, while push factors are motivators that, drawing on external factors unrelated to the individuals’ entrepreneurial characteristics, “force” these individuals to engage in entrepreneurship. While pull factors have positive roots (e.g., need for achievement, opportunities for social development), push factors have negative connotations (e.g., unemployment, dissatisfaction with the current situation) such that push-driven individuals opt for self-employment not because it is their preferred option but because it is a better option than those available, or their only option (van der Zwan et al., 2016). However, there is no clear understanding of “which” of these factors (push versus pull) is more influential on individuals’ entrepreneurial intention. As such, focusing on analyzing the separate influence of push and pull factors on entrepreneurial intention will help respond to Carsrud and Brännback's call (2011), and will advance the existing literature on the type of motivation that further enhances entrepreneurial intention.

In doing so, we will integrate Push-Pull Theory (Amit & Muller, 1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010) into Krueger's Model of Entrepreneurial Intention (Krueger, 1993; Krueger & Brazeal, 1994, 2000). This model combines concepts from the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991) and Shapero and Sokol's (1982) Entrepreneurial Event Model to describe how perceptual factors, such as perceived feasibility (i.e., feeling one is capable of starting a venture) and desirability of venture creation (i.e., appeal of starting a venture), are key in determining entrepreneurial intention. This integration will respond to recent calls to integrate existing, mainstream models of entrepreneurial intention to better understand the phenomenon of entrepreneurial intention (i.e., Esfandiar, Sharifi-Tehrani, Pratt & Altinay, 2019), and will enrich Push-Pull Theory by taking the cognitive/perceptual approach to understanding this phenomenon from Krueger's Model. With such a cognitive approach in mind (see Ahmad, Xavier & Bakar, 2014; Baron, 2004; Shaver & Scott, 1991), this study will seek to test whether, as Reynolds, Camp, Bygrave, Autio and Hay (2001) already anticipated, the underlying mechanisms leading push and pull individuals to start a venture are divergent. Specifically, we will focus on two perceptual variables, namely, perceived risk and opportunity recognition, as the mechanisms underlying this relationship(s). These were selected based on earlier research indicating both have been previously identified as direct consequences of push-pull motivations (Block, Sandner & Spiegel, 2015), as well as key predictors of entrepreneurial intention (Baron, 2004, 2014). Additionally, by invoking feelings of “anxiety” and “novelty to explore”, perceived risk and opportunity recognition are closely linked to perceived feasibility and desirability of venture creation, respectively. This leads us to predict that perceived risk and opportunity recognition could play a mediating role (in a similar way as perceived feasibility and desirability of venture creation are also predicted to play, see Krueger et al., 2000) in the relationship(s) between push–pull factors and entrepreneurial intention that we aim to analyze in this study.

We therefore aim to explore the following two important questions: Do push and pull-driving factors each play a role, and, if so, which role, in encouraging entrepreneurial intention? Are perceptual variables, such as perceived risk and opportunity recognition, key mechanisms through which this influence occurs? In short, the main aim of this study is to analyze the influence of push and pull factors on individuals’ entrepreneurial intention, examining the mediating role of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. Testing these relationships contributes to the literature in three ways. First, this study helps answer Carsrud and Brännback's (2011) question about the type of motivation that most drives entrepreneurial intention. Second, this research advances the emerging call for the need to expand Krueger's Entrepreneurial Intent Model (Elfving, Brännback & Carsrud, 2017; Krueger, 2009) by incorporating new, more specific perceptual variables that provide greater information about the environment (perceived risk, opportunity recognition) as critical antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Third, our study advances the emerging research field on the need to integrate existing mainstream models of entrepreneurial intention (Esfandiar et al., 2019). Specifically, drawing on cognitive theory (Ahmad et al., 2014; Baron, 2004), which considers that potential entrepreneurs’ intentions to create a venture are influenced by the perceptions that are cognitively formed about the environment, our research integrates Krueger's Model (Krueger, 1993) and Push-Pull Theory (Amit & Muller, 1995) into a unified model. This will lead to an integrative view on how perceptual variables, such as perceived risk and opportunity recognition, link push-pull factors to entrepreneurial intention, which, despite having long been demanded by the literature (Schwarz, Wdowiak, Almer-Jarz & Breitenecker, 2009), has hitherto been ignored (Dawson & Henley, 2012; van der Zwan et al., 2016).

The rest of the study is organized as follows. The second section reviews the extant literature on the theoretical background and develops the hypotheses of the study. The third section describes the research method, including sample and procedure, measures, and data analysis. The fourth section discusses the results. Finally, the fifth section presents the discussion and conclusions, incorporating implications for entrepreneurial intention theory and practice, together with limitations and future research directions.

2Theoretical background and development of hypotheses2.1Push–Pull driving factors and entrepreneurial intentionEntrepreneurial intention is defined as the commitment to starting a new venture (Krueger, 1993), being the means to better predict and explain the process of entrepreneurship (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989). Starting a venture is not a simple stimulus-response behavior, but is a complex process based on planned behavior over time and in which many factors come into play (Fayolle & Liñán, 2014). One of the decisive factors in forming and developing entrepreneurial intention is that of entrepreneurial motivations (Fayolle, Liñán & Moriano, 2014). The meta-analysis by Collins, Hanges and Locke (2004), for example, confirms that entrepreneurial motivations are critical for positively shaping the choice of an entrepreneurial career, and therefore in forming individuals’ entrepreneurial intention. In fact, entrepreneurs have a tendency not to define themselves as entrepreneurs but rather by the motives that lead them to do what they do (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011).

Entrepreneurial motivation represents the purpose or psychological cause of starting a venture, such that the greater the importance given to that motivation, the more likely the person is to form action plans aimed at starting a venture (Fayolle et al., 2014). Under the umbrella of the Push-Pull theory (Amit & Muller, 1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010; Gilad & Levine, 1986; Kirkwood, 2009; Thurik et al., 2008), the extant research on entrepreneurial motives notes a clear distinction between push and pull factors (Tipu, 2016), as a way to understand entrepreneurial intention. Most studies find that the entrepreneurial population is more frequently attracted to self-employment by "pull" motives, such as autonomy (independence, freedom), income, wealth, challenge, recognition, and status (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Segal, Bogia & Schoenfeld, 2005), while the influence exerted by push factors is lower (van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006). In fact, pull variables, such as autonomy or independence, tend to be those with the greatest influence on entrepreneurs when making the decision to start a new venture (van Gelderen & Jansen 2006). In particular, the quest for greater schedule flexibility, a better work-family balance or being one's own boss, are important driving forces for the formation of the entrepreneurial intention among individuals (Dawson & Henley, 2012).

However, individuals may also be pushed into entrepreneurship by necessity (Dawson & Henley, 2012; Thurik et al., 2008), which is a concept invoked to explain the “push” motives (e.g., poverty, survival, lack of choice in work). Push factors are personal or external factors (e.g., being passed over for promotion, unemployment, dissatisfaction with one's current professional situation) that often involve unpleasant connotations (Kirkwood, 2009) and comprise negative impulses, such as a lack of alternative career opportunities, that drive a person to reduce the resulting tension by starting their own venture (Casrud & Brännback, 2011). Although push factors have been observed to have negative implications in terms of entrepreneurial survival and success (Amit & Muller, 1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010), research shows that push drivers can also play a fundamental role, together with pull factors, in driving individuals to decide to start a new venture (Dawson & Henley, 2012; Giacomin et al., 2011; van der Zwan et al., 2016). Starting a venture out of necessity can at first sight be an activity that generates reluctance, yet the need to meet lower-order needs (e.g., need to support the family with additional incomes, earning a living, difficulty in finding other work alternatives) may exert a positive influence on the intention to start a venture. Thus, although push factors typically entail negative connotations (Amit & Muller, 1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010), they may also contribute positively to the development of a greater entrepreneurial intention (Dawson & Henley, 2012; van der Zwan et al., 2016).

Overall, both an “economy of self-fulfillment” (pull driving factors) and an “economy of need” (push driving factors) may generate an individual's willingness to start a new venture. Both types of motivations may be critical antecedents of the formation of entrepreneurial intention. Thus,

H1a: There is a positive relationship between push factors and entrepreneurial intention.

H1b: There is a positive relationship between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention.

In accounting for factors that influence entrepreneurship, the literature does not focus exclusively on motivations, but also emphasizes other cognitive elements, such as subjective perceptions (Krueger, 1993). Perceptions form and emerge in one's mind and represent how the external environment is captured through the senses and cognition (Arafat & Saleem, 2017). Without ignoring their strongly subjective basis, such representations also tend to involve an objective dimension emanating from more objective, environmental and informational signals (e.g., market dynamics, economic downturn). Thus, these perceptions affect the way people understand the situation, and play a role in affecting their intention to start a new venture (Arenius & Minniti, 2005).

A review of the classic entrepreneurial intention model developed by Krueger and his associates (i.e., Krueger, 1993, 2009; Krueger et al., 2000) reveals the important and intermediary role of these perceptual elements in determining entrepreneurial intention (Elfving et al., 2017). In particular, this model identifies two critical intermediate perceptual variables in the process: perceived feasibility and perceived desirability, which refer, respectively, to the extent to which people believe they are capable of starting a venture, and the level to which they find venture creation attractive (Krueger et al., 2000). Given the strong influence of Shapero and Sokol's (1982) model on Krueger et al. (2000) model, and the emphasis of the former on the role of certain displacing aspects that could give rise to initiating the entrepreneurial intention process (e.g., push–pull factors; Krueger, 2009), both perceived feasibility and desirability may play a mediating role between personal motives to start a venture and entrepreneurial intention. Empirical research has corroborated such a role. Solesvik (2013), for example, finds the perceived relative ease of venture creation (perceived feasibility, Krueger et al., 2000) as fully mediating the effect of entrepreneurial motivation on individuals’ intention to start a new venture. Tognazzo, Gianecchini and Gubitta (2017) also reveal how perceived behavioral control and attitude toward entrepreneurship, which are similar to perceived feasibility and desirability, respectively (Krueger et al., 2000), mediate between individual motivation and entrepreneurial intention. These findings are in line with the premises of the cognitive/perceptual theory (Ahmad et al., 2014; Baron, 2004), which emphasizes that everything we think, say or do is influenced by mental processes –the mechanisms through which we acquire, transform and use information (Baron, 2004). Under this perspective, the formation of perceptions on the environment would be the basis for building entrepreneurial intention (Arafat & Saleem, 2017) and, hence, perceptual variables could be the missing link between push–pull factors and entrepreneurship intention.

Despite the important mediating role that perceived feasibility and desirability may play in determining entrepreneurial intention, none of these variables properly captures objectivity and specificity. Other perceptual variables, such as perceived risk and opportunity recognition, might do this much better (Baron, 2004). For example, perceived risk in venture creation involves evaluating the risk expectations of such an act (Monsen & Urbig, 2009), while opportunity recognition entails objective evaluation and apprehension of the environment (Gaglio & Katz, 2001). Although they are both perceptual, they offer more objective and specific information upon which to build perceived feasibility and desirability of venture creation and may act as better mediators in the process that leads push-pull factors to determine entrepreneurial intention. Indeed, push and pull factors, as negative and positive displacements, respectively, that is, events that disrupt an individual's life and pave the way for them to reconsider an entrepreneurial career (Krueger, 2009; Shapero & Sokol, 1982), can affect the assessment and perspective of the situation (Maâlej & Cabagnols, 2020). This, consequently, shapes perceived risk and opportunity recognition, which in turn should affect the willingness to start a new venture. In fact, research reveals that opportunity recognition and perceived risk (i.e., fear of failure, Arenius & Minniti, 2005) can act as conductors between factors related to individual (e.g., motivations) and entrepreneurial intentions (Carmelo-Ordaz, Diánez-González & Ruiz-Navarro, 2016), which we explain in detail below.

2.2.1Push–Pull factors and entrepreneurial intention. the mediation of perceived riskPush factors can negatively influence entrepreneurial intention through their effects on the perceived risk of venture creation. Support for our mediation hypothesis requires several types of evidence. First, there must be a positive and significant relationship between push factors and perceived risk. This is likely to occur because the literature has shown that the motivational factor is a key element in explaining the difference in risk perceptions between individuals that start a new business and those that do not (Busenitz, 1999). In this regard, pull-and push-driven entrepreneurs differ in risk aversion (Block & Wagner, 2010); while the former are willing to take risks, the latter exhibit less risk tolerance (Block et al., 2015; van der Zwan et al., 2016), which would augment their perceived risk of venture creation (Sitkin & Weingart, 1995). Push factors, such as unemployment, low family income (Kumar, 2007) or dissatisfaction with one's current situation (van der Zwan et al., 2016), also involve a willingness to become self-employed based on frustration and lack of challenge (Amit & Muller 1995). These motivations stem from negative emotions that may lead to perceive venture creation as risky (Nabi & Liñán, 2013).

Second, there must be a negative and significant link between perceived risk and entrepreneurial intention. This may happen because risk perception is considered a core component of the general theory of entrepreneurship and plays a central role in the entrepreneurial decision-making process (Elston & Audretsch, 2011). In this sense, Kuechle (2013) indicates that risk is implicit in the entrepreneurial process, in starting, for example, a new venture, as it involves a series of projected results that are difficult to achieve and that, therefore, make this decision risky (Aldrich & Martinez, 2001). Thus, perceived risk, conceived as the evaluation of the risks inherent in pursuing an action (Block et al., 2015; Monsen & Urbig, 2009; Nabi & Liñán, 2013), is likely to underlie the decision to start a new venture, such that the higher the perceived risk, the lower is the willingness to start a new venture. Recent research supports this contention, revealing, for example, that perceived economic risk has a negative effect on the decision to start a new venture (i.e., Simon, Houghton & Aquino, 2000) and on the entrepreneurial feasibility and desirability of the entrepreneurial activity, which are commonly considered as critical perceptual variables in encouraging entrepreneurial intention (Giordano-Martínez, Herrero-Crespo & Fernandez-Laviada, 2017).

In all, push factors (i.e., unemployment, low family income, dissatisfaction with one's current situation) represent negative displacements (Krueger, 2009; Shapero & Sokol, 1982). These motivations stem from negative emotions, so are likely to lead individuals to have an increased perception of the risk involved in venture creation, which, in turn, would decrease their willingness to start a new venture. Therefore, the evidence presented above leads us to formally propose the following hypothesis:

H2a: Perceived risk mediates the relationship between push factors and entrepreneurial intention in such a way that push factors will have a negative indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through perceived risk.

Unlike push factors, which may make individuals perceive risk in venture creation, pull factors (e.g., self-fulfillment, social and professional prestige, a flexible working schedule, the chance to put one's ideas into practice, Ruda, Ascúa, Martin & Danko, 2014) may help reduce the perceived risk in venture creation (Eijdenberg & Masurel, 2013). Pull-driven individuals tend to be proactive and optimistic and tend to have fewer negative inclinations about the financial support required during the start-up process (van der Zwan et al., 2016). Furthermore, by being self-confident about their own abilities (Dalborg & Wincent, 2015) and more enthusiastic about their venture expectations (Block et al., 2015), pull-driven individuals tend to anticipate fewer barriers in venture creation (i.e., greater feasibility) and thus perceive venture creation as less risky (Brindley, 2005).

Thus, given that pull factors may negatively influence perceived risk, and that perceived risk, as noted earlier, has a negative impact on entrepreneurial intention (Tognazzo et al., 2017), pull factors may have a positive indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention by reducing the level of perceived risk in venture creation. Accordingly,

H3a: Perceived risk mediates the relationship between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention in such a way that pull factors will have a positive indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through perceived risk.

As part of our effort to develop a comprehensive model to help understand the impact of push-pull factors on entrepreneurial intention, we are also interested in the potential mediating role of opportunity recognition. Defined as the entire set of external circumstances that make a successful entrepreneurial venture possible (Stuetzer, Obschonka, Brixy, Sternberg & Cantner, 2014), opportunity recognition involves perceiving an innovative way of obtaining profit that has not been, or is not being, exploited (Costa, Santos, Wach & Caetano, 2018). Opportunity recognition is of interest here because it is a broad, direct reflection of the nature of entrepreneurial intention (Baron, 2006), which might be impacted by push-pull factors.

As with our previous set of mediation hypotheses (H2a and H3a), for opportunity recognition to mediate between push factors and entrepreneurial intention, there must firstly be a significant and negative relationship between push factors and opportunity recognition. This is likely to occur because push entrepreneurs are not characterized as being motivated by the recognition of attractive business opportunities. Rather, they are viewed as “forced” entrepreneurs (Masurel, Nijkamp & Vindigni, 2004) that opt to start a venture because they have no better choices for work or earning a living (Block & Wagner, 2010). Thus, in push-driven entrepreneurship, the business may evolve into an attractive idea over time but is not typically conceived as such from the beginning (van der Zwan et al., 2016), which would explain why push entrepreneurs tend to exhibit lower opportunity recognition.

Second, it is also required that the recognition of an opportunity in the economic environment, which is a rich source of opportunities (Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, 1993), be positively and significantly related to the willingness to start a new venture (Baron & Ensley, 2006). There is a good likelihood of this occurring, given that a business opportunity refers to the entire set of external events that lead to the identification of a brilliant and successful business idea (Stuetzer et al., 2014). Hence, when individuals recognize an opportunity, they are likely to subjectively and positively assess the probability of success (Carmelo-Ordaz et al., 2016), which might activate a strong willingness to start a new venture. In practice, opportunity recognition is the first stage of the entrepreneurial process to be activated (Costa et al., 2018), such that the perception of a profit-making opportunity (Holcombe, 2003) would positively impact entrepreneurial intention.

Overall, push factors are expected to negatively influence opportunity recognition, which in turn, should have a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention. Accordingly,

H2b: Opportunity recognition mediates the relationship between push factors and entrepreneurial intention in such a way that push factors will have a negative indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through opportunity recognition.

Finally, two further conditions are also required for opportunity recognition to mediate between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention. First, there must be a significant and positive relationship between pull factors and opportunity recognition. This is likely to occur since pull-related factors are connected with people envisioning new, unexploited market opportunities (Block et al., 2015; Dawson & Henley, 2012) as well as with individuals taking full advantage of market opportunities (van der Zwan et al., 2016). As such, because pull factors (i.e., autonomy, being one's own boss) involve a willingness to do something different and express one's creativity (van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006), we believe that this type of motivation may help individuals to recognize opportunities more easily. When individuals express the need to explore new things and express their creativity, the recognition of new business opportunities is more than likely (Hansen, Shrader & Monllor, 2011). As a second condition, there must be a positive and significant relationship between opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial intention, as already discussed. Indeed, opportunity recognition plays a positive role in individuals perceiving venture creation as attractive and desirable (Baron, 2006; Costa et al., 2018) and is, therefore, a trigger of entrepreneurial intention (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011; Krueger, 2009). Thus, pull factors should shape entrepreneurial intention positively, by increasing opportunity recognition. Accordingly,

H3b: Opportunity recognition mediates the relationship between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention in such a way that pull factors will have a positive indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through opportunity recognition.

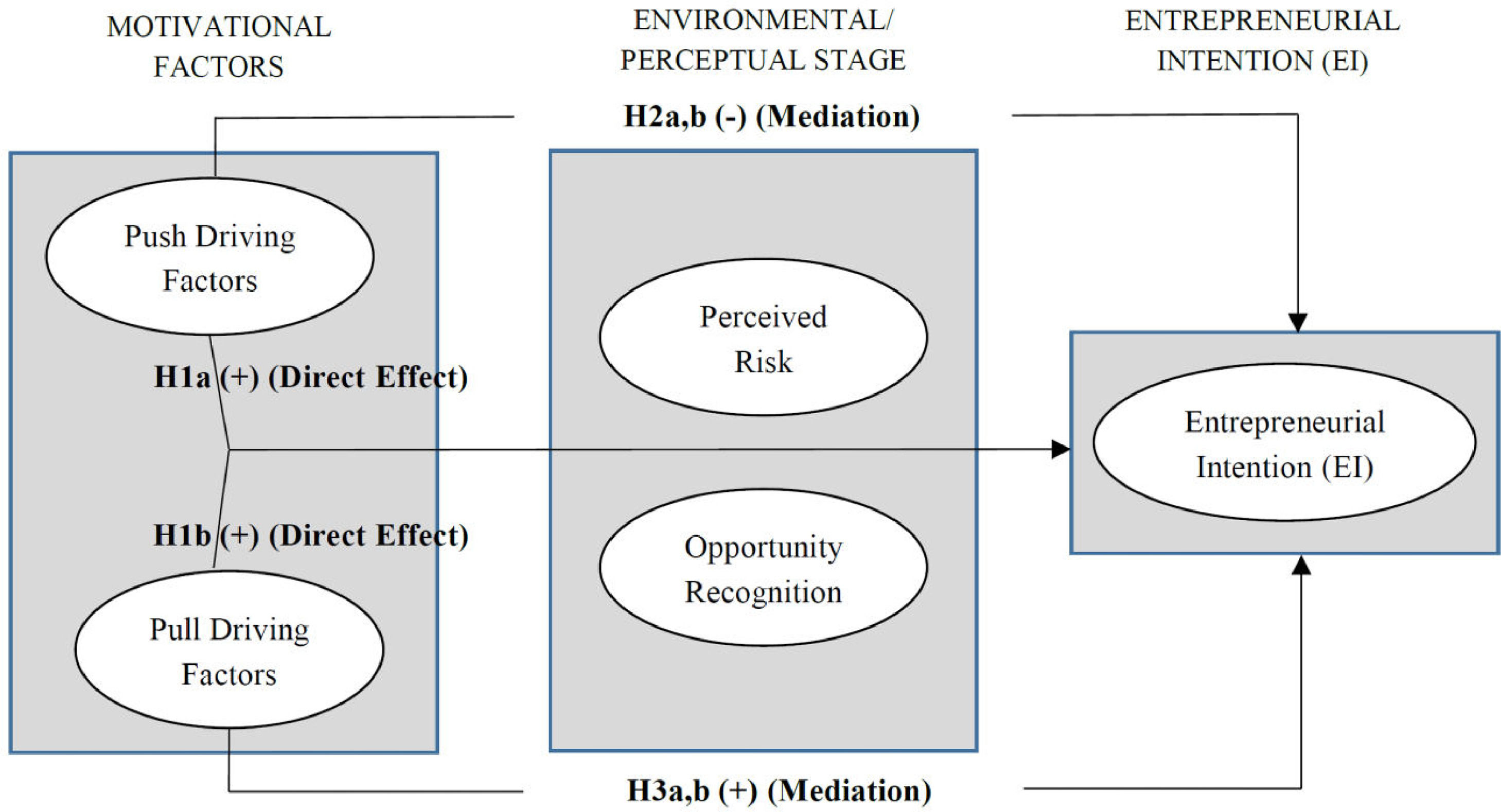

In short, this paper predicts that, in forming entrepreneurial intention, a motivational stage needs to be considered, through which both push and pull factors are positively related to entrepreneurial intention (H1a, H1b). This study next predicts that a perceptual/environmental stage comes into play, in which the relationships between push and pull factors and entrepreneurial intention are mediated by perceived risk and opportunity recognition. Specifically, we predict that push factors may negatively influence entrepreneurial intention by increasing individuals’ perceived risk in venture creation (H2a) and lowering their opportunity recognition (H2b). We also predict that pull factors may positively influence entrepreneurial intention, by lowering a person's perceived risk of launching a new venture (H3a) and increasing their capacity of opportunity recognition (H3b). Fig. 1 shows the conceptual model we intend to test.

Theoretical Model: Push-Pull Factors Relationship to Entrepreneurial Intention

Notes. H1a and H1b: Push and Pull factors have a positive direct effect on EI.

H2a,b: Perceived Risk and Opportunity Recognition mediate between Push Factors and EI; Push factors have a negative indirect effect on EI through increasing Perceived Risk and lowering Opportunity Recognition.

H3a,b: Perceived Risk and Opportunity Recognition mediate between Pull Factors and EI; Pull factors have a positive indirect effect on EI through lowering Perceived Risk and increasing Opportunity Recognition.

A survey was used to gather data from university undergraduates, which is an important target population for promoting entrepreneurship (Shirokova, Tsukanova & Morris, 2018). University students are at a stage of life in which people show the greatest interest in starting a new venture (Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2016) and represent a population group that is soon to enter the job market (Hattab, 2014). Thus, understanding how to improve their entrepreneurial intention is crucial for offering them an employment alternative, which can help reduce unemployment rates and improve a country's economic conditions.

We tested the questionnaire for clarity, readability, and suitability, using a group of experts and a sample of 34 students enrolled in different degree courses and campuses in Spain. After completing necessary revisions and receiving consent from the corresponding professors, the questionnaire was distributed to a random sample of 630 undergraduate students spanning five campuses and seven degree courses in the central-southern area of Spain. This sample size was large enough to obtain a sampling error far below the permissible threshold of ±5.0, considering a population of 25,876 students in this central-southern Spanish region (Aaker & Day, 1990). The sampling error for 630 students is 3.86% (confidence level of 95%, p = q = 0.5), which assures that the sample size is representative of the entire student population in this region.

In order to increase the sample size, we directly distributed the surveys to undergraduate students at the beginning of their in-person classes. This selection was as random as possible, on the basis that only 50% of the students on an enrollment list previously provided by the professor were randomly selected. We asked all these students to respond to the questionnaire during class time, so the researchers could collect the data themselves. In general, we received responses in the classroom. However, if a student on the enrollment list was absent that day, a physical postbox was available for them to submit their responses. In total, 616 usable responses were received (97% response rate). To mitigate social desirability bias (SDB) and common method variance (CMV), we followed Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff (2003) recommendations. For example, to reduce SDB, anonymity was guaranteed, as the survey asked for vague demographic information (see Table 1 for respondents’ profiles). Additionally, to mitigate CMV: a) the survey included a psychological separation between predictors and criterion variables to make them appear unrelated, b) the study variables were intermingled with other variables related to entrepreneurial intention, but which acted as distractors, and c) all items were kept simple, specific, and concise.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample.

SD = Standard Deviation.

When measures are used to examine a latent construct, the researcher can design reflective or formative indicators (MacKenzie, Podsakoff & Jarvis, 2005). While reflective measurements are highly correlated indicators that may be caused by the latent construct, formative measures involve indicators that determine the construct without necessarily being correlated (Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2017). In our survey, following MacKenzie et al. (2005) four criteria to distinguish between these two types, all variables were reflective, except push- and pull-driving factors. For MacKenzie et al. (2005), a construct can be formative or reflective, respectively, if: 1) the indicators define aspects of the construct rather than manifestations of it; 2) the indicators capture a unique concept of the construct or are instead interchangeable; 3) the indicators do not necessarily covary or instead must do so; and 4) the indicators are not expected to have the same antecedents and/or consequences, or are instead expected to. As such, because the indicators used for the push and pull factors are the result of previous research aimed at uncovering the range of different aspects that describe push- and pull-driven entrepreneurs (Dawson & Henley, 2012; van der Zwan et al., 2016), a formative approach seems appropriate.

All measures were linguistically, semantically, and culturally adapted from the instrument used in the international research project “Starting up Businesses and Entrepreneurship by Students” (GESt Study; Ruda et al., 2014), which represents a partnership between different universities to compare criteria that influence students’ start-up propensity across European and Latin American countries. The questionnaire used Likert-type scales but also included other response formats (i.e., yes/no, 0% to 100%). It also used a single-item measurement approach for all reflective variables, which is not uncommon in entrepreneurship research (i.e., Hoogendoorn, Van der Zwan & Thurik, 2019; Krueger et al., 2000; Tumasjan & Braun, 2012). In fact, such an approach is valid and recommended in empirical research (Ganzach, Ellis, Pazy & Ricci-Siag, 2008), especially if both the object and the attribute of the construct are concrete in the respondents’ minds (Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007), as seems to be the case with the variables for which this approach is used here (i.e., opportunity recognition, perceived risk, entrepreneurial intention).

Push Factors. Two motivations that characterize entrepreneurs driven by necessity were used: “option for unemployment” and “option for earning a living.” Both items define and capture unique aspects of push-driven entrepreneurs and need not be strongly correlated as they may have different antecedents and/or consequences, thus suggesting a formative approach (MacKenzie et al., 2005). On a four-point scale (1 = “not important,” 4 = “very important”), respondents rated how important each of these two aspects would be in influencing them to start their own venture.

Pull Factors. To build this variable, we used five characteristic motivations of opportunity-driven (pull-driven) entrepreneurs: “to have power or command a group of people,” “to become one's own boss,” “to self-realize,” “to gain social, professional prestige,” and “to start up one's ideas”. These items fulfilled MacKenzie et al. (2005) criteria for approaching this variable as formative. Respondents were asked to indicate how important each of these five aspects would be in driving them to start their own venture, using a four-point scale (1 = “not important,” 4 = “very important”).

Opportunity Recognition. We measured opportunity recognition with one single item: “Have you currently identified a market gap or opportunity to initiate a new venture?” (0 = “not yet,” 1 = “yes, absolutely”). This choice is not uncommon in the literature, and various are the examples in earlier research (Dyer, Gregersen & Christensen, 2008; Tumasjan & Braun, 2012).

Perceived Risk. By comparing a multi-item to a single-item approach, Ganzach et al. (2008) showed that the latter has better validity for measuring risk perception. Guided by this finding and the example of others (Frias, Popovich, Duhan & Lusch, 2020; Hoogendoorn et al., 2019), we then measured the extent to which venture creation is perceived as risky with one item: “Is it very risky to create a new venture?” (1 = “not risky,” 11 = “risky”).

Entrepreneurial Intention. As others have done in previous research (see Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006; Krueger et al., 2000), we measured this reflective variable with a question adapted from Guerrero, Rialp and Urbano (2008), which was measured as a percentage (0% to 100%): “How likely are you to start your own venture at some point in the near future?”

Control Variables. Demographic variables are typically used when assessing entrepreneurs (Robinson, Stimpson, Huefner & Hunt, 1991) and have been shown to affect entrepreneurial intention (Pfeifer, Sarlija & Zekic-Susac, 2016). Accordingly, we controlled for age, gender, human resource (HR) management experience, and having an entrepreneurial family/social circle (cf., Çelik, Yıldız, Aykanat & Kazemzadeh, 2021; Delmar & Davidsson, 2000; Moreno-Gómez, Gómez-Araujo, Ferrer-Ortíz & Pena-Ruiz, 2022; Pfeifer et al., 2016; Santos, Azam-Roomi & Liñán, 2016). Age was included because older people are less willing to invest their time and resources in an activity that involves doubtful and uncertain paybacks (Hatak, Harms & Fink, 2015). Gender was also selected because it has been shown that men consider an entrepreneurial career more acceptable, feasible, and desirable than women do (Moreno-Gómez et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2016), and thus have a stronger entrepreneurial intention (Haus, Steinmetz, Isidor & Kabst, 2013). Being experienced or not in HR management was also selected because such experience may help an individual to be more self-efficacious as well as more inclined to perceive the creation of a new venture as a relatively feasible activity (Miralles, Giones & Riverola, 2016). In addition, specific HR management experience is likely to help an individual better identify the abilities needed to be successful in starting a new venture (self-efficacy, personal perseverance, social skills) or the most entrepreneurially talented people with which to initiate a successful, new venture (cf., Markman & Baron, 2003). Finally, having family or friends that run a business can help individuals perceive entrepreneurial activity as attractive and feasible and can help them feel that emotional or technical support can be obtained if needed (Hanlon & Saunders, 2007). We thus created dummy variables for all these control variables, except age (measured as number of years): gender (0 = male, 1 = female), HR management experience (0 = no, 1 = yes) and entrepreneurial family/social circle (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Finally, because students pursuing business-related degrees are more familiar with entrepreneurship concepts, subjects, and theories, they are more likely to show stronger entrepreneurial intentions (Pfeifer et al., 2016): Thus, we also controlled for the type of university degree. We coded this as a categorical variable according to three categories: engineering degree (telecommunications engineering, building engineering), non-business-related degree (language and speech therapy, social education), and business-related degree (economic sciences, business administration, labor relations), with business-related degree representing a reference point to interpret the effects of this control variable.

3.3Data analysisTo test our hypotheses, we used partial least squares (PLS) via Smart PLS 3.2.7. (Ringle, Wende & Becker, 2015). PLS is a distribution-free approach and allows for non-interval-scaled data and both reflective and formative measures (Hair et al., 2017), so it is suitable for testing our model, which includes different measurement scales (nominal, ordinal, and interval-scaled variables) and approaches (formative, reflective). PLS allows for the unrestricted use of single-item constructs, which is not uncommon in the PLS literature (Ringle, Sarstedt & Straub, 2012) and does not involve a great loss of predictive validity, even if these constructs are used as mediators (Hair et al., 2017). In addition, like other structural equation modeling techniques, PLS is especially suitable for testing the mediation hypotheses included in our study (James, Mulaik & Brett, 2006). Bootstrapping (5000 resamples) was used to generate standard errors and t-statistics to test the hypotheses (Hair et al., 2017) and test whether the indirect effects were significant, which is an important criterion for establishing mediation (Zhao, Lynch & Chen, 2010).

4Results4.1Common method variance (CMV)Two tests showed that CMV was not a serious problem in this study. First, we ran Harman's (1976) one-factor test to determine whether a majority of the covariance among measurements could be explained by a single factor. The exploratory factor analysis of all the items revealed six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. These accounted for 58% of the variance, and the variance of the first factor accounted for only 17% of the variance, indicating that CMV was not an issue (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Second, a variable that was theoretically unrelated to any of the study variables (i.e., “How important is university education for entrepreneurs”, 1 = “not important at all,” 4 = “very important”), showed non-significant correlations with none of the study variables, as recommended (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). Furthermore, the second-smallest correlation between the marker variable and the study variables (rm = –0.003) was partialled out from the uncorrected correlations to check for the magnitude and significance of this bias (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). After controlling for this bias, all the correlations that were previously significant remained significant, so this bias is unlikely to have affected our findings.

4.2Measurement modelIndices supporting the effective measurement of the formative constructs (i.e., push factors, pull factors) appear in Tables 2 and 3. Table 3 also shows item loadings for the reflective variables. Finally, Table 4 shows the correlations between the study variables.

Exploratory Factor analysis (EFA) of Push and Pull Driving Factors.

Notes: Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sample adequacy = 0.611, which is higher than 0.6 as the minimum threshold required (Kaiser & Rice, 1974). Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 = 496.514, df = 21, p < 0.00) was also significant, as recommended (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010).

Measurement Model: Item Loadings and Weights.

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns: not significant. VIF = Variance Inflation Factor.

Mean, Standard Deviations and Correlation Matrix.

All the correlations between 0.08 and 0.10 are significant at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All remaining correlations equal or above 0.11 are significant at p < 0.01 (two-tailed). EI = Entrepreneurial Intention.

Gender: 0 = male, 1 = female. Type of University Degree: 0 = non-business-related degree, 1 = business-related degree.

With regard to the single-item measures used in this study, these variables, which are manifest (i.e., only one item captures their content), are included as reflective in PLS. Because, in the case of these variables, the relationship between the construct and the item is 1, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) reaches the value of 1, and traditional reliability and validity criteria do not apply (Hair et al., 2017).

Traditional reliability and validity criteria do not apply either when a formative mode is used (Hair et al., 2017). However, in the specific case of formative approaches, other procedures can be used. First, in terms of construct-level assessment, both formative constructs (pull and push factors) fulfill the discriminant validity criterion; the correlations of these formative variables with other study variables are far below the threshold of 0.7, as recommended (Table 4; Urbach & Ahlemann, 2010). Furthermore, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) revealed that push and pull factors are different constructs: two principal factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 emerged, and each push and pull item loaded on their respective factors, as expected (see Table 2). Second, at the indicator level, tests for multicollinearity involving the formative variables revealed minimal collinearity; the variance inflation factor (VIF) of all items ranged between 1.15 and 1.37 (Table 3), below the threshold of 5.0 (Hair et al., 2017), thus indicating that all the formative indicators contributed to form their corresponding formatively approached constructs. Thus, both formative constructs (push and pull factors) are appropriately measured for the analysis of the current study. However, some indicators of these formative constructs were more important than others. With regard to push factors, “option for unemployment” contributed significantly to the formation of the construct (ω = 0.66, p < 0.05), while “option for earning a living” was not significant (ω = 0.55, ns): However, this indicator reflects a t-value above 1.0, and so it adds more information than noise (Konradt, Christophersen & Schaeffer-Kuelz, 2006). In order of importance in building “pull factors,” the item “to self-realize” contributed significantly (ω = 0.58, p < 0.001), as did “to start up one's ideas” (ω = 0.46, p < 0.01). However, “to gain social and professional prestige”, “to have power or command a group of people”, and “to become one's own boss” showed non-significant weights (ω = 0.13, ns; ω = 0.25 ns; ω = 0.13, ns). Nevertheless, because their loadings were positive and significant (λ = 0.48, p < 0.001; λ = 0.43, p < 0.01; λ = 0.44, p < 0.01, Table 3), these items still helped form the construct and were retained, as recommended (Hair et al., 2017).

4.3Effects of control variables on entrepreneurial intentionThe model we present to explain entrepreneurial intention includes small proportions of variance explained by the control variables (Table 5). Specifically, having HR management experience positively influences entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.16, p < 0.001), in line with previous research (Delmar & Davidsson, 2000). Our results also reflect that exposure to an environment in which parents, relatives and/or friends are entrepreneurs has a positive influence on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.14, p < 0.001), which is likely to occur because such an environment provides support, legitimacy, and desirability with respect to an entrepreneurial career (Santos et al., 2016). Another important finding is that the students’ entrepreneurial intention was negatively affected by age (β = –0.08, p < 0.1) and non-business-related studies (β = –0.09, p < 0.05). These findings corroborate previous research that indicates older individuals are less likely to start a venture (Kautonen, 2008), being more reluctant to invest the time involved in the entrepreneurial process (Hatak et al., 2015). These findings are also in line with previous research showing higher entrepreneurial intention among business students (Pfeifer et al., 2016), given that their greater exposure to entrepreneurial education tends to guide them towards entrepreneurial undertakings (Kautonen, van Gelderen & Fink, 2015) and increase their confidence and self-efficacy to start their own business (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994). Finally, the results reveal that gender does not influence entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.02, ns). Although some research suggests there exists higher entrepreneurial intention among men (Dawson & Henley, 2015; Santos et al., 2016), who consider an entrepreneurial career more acceptable, feasible, and desirable than do women (Santos et al., 2016), other studies (i.e., Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015), including ours, find no such relationship with gender.

Structural Model Results: Direct Effects and Variance Explained.

For testing model variables’ effects (one-tailed test): *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns: not significant.

For testing control variables’ effects (two-tailed test): *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05, †p < 0.1, ns: not significant.

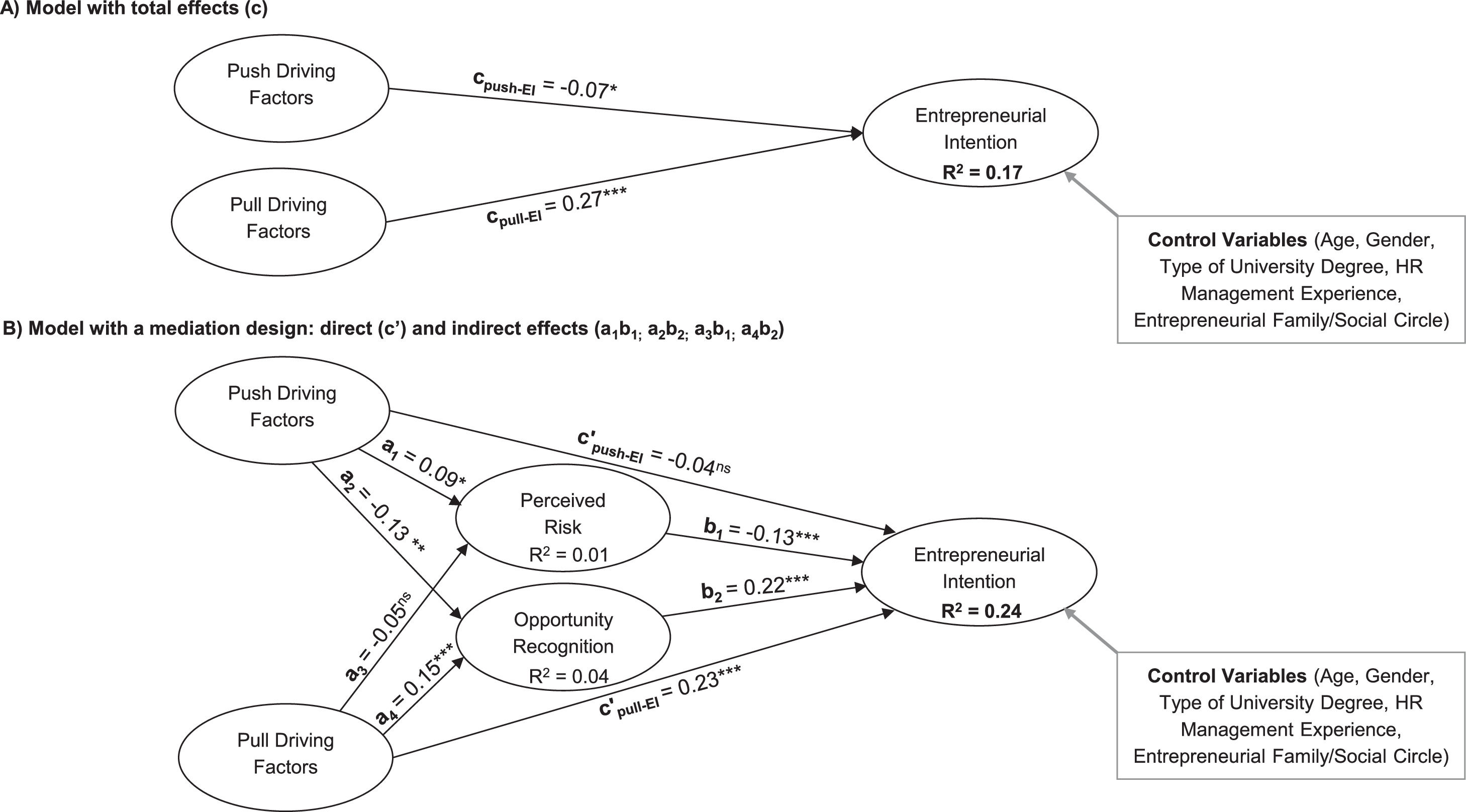

Tables 5 and 6, and Fig. 2 all show hypothesis-testing results. With regard to the impact of push-pull factors on entrepreneurial intention, push factors were not directly related to entrepreneurial intention (H1a; β = –0.04, ns,Table 5, Fig. 2B), whereas pull factors were positively related (H1b; β = 0.23, p < 0.001, Table 5, Fig. 2B). Thus, the results do not support H1a but do support H1b, which illustrates the significant role of pull factors in encouraging entrepreneurial intention as opposed to the non-significant effect of push factors. With regard to the mediation tests, we used Baron and Kenny's (1986) three-step procedure, which establishes that, for mediation to exist: 1) the predictor must affect the mediator(s), 2) the mediator(s) must relate to the outcome, and 3) a significant link between the predictor and the outcome decreases in size (partial mediation) or ceases to be significant (full mediation), when the mediator(s) is (are) included.

Push–Pull Factors and Entrepreneurial Intention. The Mediating Effects of Perceived Risk and Opportunity Recognition.

| Total Effect of Push Factors on EI | Direct Effect of Push Factors on EI | Indirect Effects of Push Factors on EI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coefficient (t-value) | Path Coefficient (t-value) | Indirect Effect Estimatea | Bias-Corrected Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| −0.07* (2.05) | H1a = c’= −0.04 ns (1.12) | Total = a1b1+a2b2 | −0.03* | −0.019 | −0.070 |

| H2a = a1b1 (via Perceived Risk) | −0.01* | −0.004 | −0.036 | ||

| H2b = a2b2 (via Opportunity Recognition) | −0.02* | −0.054 | −0.010 | ||

| Total Effect of Pull Factors on EI | Direct Effect of Pull Factors on EI | Indirect Effect of Pull Factors on EI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coefficient (t-value) | Path Coefficient (t-value) | Indirect Effect Estimatea | Bias-Corrected Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| 0.27*** (7.29) | H1b = c’= 0.23*** (5.05) | Total = a3b1+a4b2 | 0.04* | 0.020 | 0.068 |

| H3a = a3b1 (via Perceived Risk) | 0.01ns | −0.004 | 0.024 | ||

| H3b = a4b2 (via Opportunity Recognition) | 0.03* | 0.017 | 0.060 | ||

*** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05, ns: not significant. EI = Entrepreneurial Intention.

Based on a bootstrap test with 5000 resamples as recommended (Hayes, 2013): This indirect effect is significant at * p < 0.05 when the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) does not contain zero.

Structural Model: Analysis of the Mediation Hypotheses

Notes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns: not significant. VIF values for the complete model range between 1.00 and 1.37, far below the 5.0 cut-off (Hair et al., 2017), so path coefficients do not suffer from multicollinearity problems.

For H2a and H2b, these three conditions were all met (see Table 5, Fig. 2). First, the predictor (push factors) significantly influences both mediators: push factors positively influence perceived risk (β = 0.09, p < 0.05) and negatively affect opportunity recognition (β = –0.13, p < 0.01). Second, each mediator significantly relates to the outcome variable: perceived risk negatively influences entrepreneurial intention (β = –0.13, p < 0.001), and opportunity recognition has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.22, p < 0.001). Finally, the significant total effect of the predictor (push factors) on the outcome variable (entrepreneurial intention) (c = –0.07, p < 0.05, see Fig. 2A) ceases to be significant when the mediators are included in the equation (c’ = −0.04, ns, Fig. 2B), in support of full mediation. A bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples testing the indirect effects involved in both these relationships is a definitive test to confirm mediation (Hayes, 2013). As Table 6 shows, when the total effect (c) of push factors on entrepreneurial intention (c = –0.07, p < 0.05) is disaggregated into its direct (c’= −0.04, ns) and indirect effects (a1b1, H2a; a2b2, H2b), the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) reveals significant indirect effects through perceived risk (a1b1 = –0.01, p < 0.05) and opportunity recognition (a2b2 = –0.02, p < 0.05). These results thus confirm that both perceived risk and opportunity recognition mediate between push factors and entrepreneurial intention and reveal that push factors do not positively and directly affect entrepreneurial intention; rather, this impact is negative and indirect, increasing the perceived risk of starting a venture (H2a) and reducing the possibility of recognizing business opportunities (H2b).

For the mediation involved in H3a and H3b, we found mixed results (see Table 5, Fig. 2). We found no support for H3a, as Baron and Kenny's (1986) first condition was not met: the pull-factor set was not significantly related to the mediator of perceived risk (β = –0.05, ns). For H3b, we did, however, find empirical support because pull factors positively influenced opportunity recognition (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), and opportunity recognition was positively related to entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.22, p < 0.001). In addition, there is a significant impact of pull factors on entrepreneurial intention (c = 0.27, p < 0.001, Fig. 2A), which decreases in size when the mediator(s) is (are) included (c’= 0.23, p < 0.001, Fig. 2B). Thus, H3b can be confirmed, although the mediation we found is partial. The bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples confirmed the existence of mediation. Table 6 shows that when the total effect (c) of pull factors on entrepreneurial intention (c = 0.27, p < 0.001) is disaggregated into its direct (c’= 0.23, p < 0.001) and indirect effects (a3b1, H3a; a4b2, H3b), only opportunity recognition mediates this relationship, in support of H3b. Although the indirect total effect was significant (a3b1 + a4b2 = 0.04, p < 0.05, Table 6), only the indirect effect through opportunity recognition was actually significant (a4b2 = 0.03, p < 0.05, Table 6). The indirect effect through perceived risk was not significant (a3b1 = 0.01, ns,Table 6), which leads us to support H3b but reject H3a. Thus, only opportunity recognition mediates the relationship between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention. This mediation is, however, partial, given that the direct effect of pull factors on entrepreneurial intention continues to be significant, which indicates that other mediators omitted may exist (Zhao et al., 2010).

Overall, except H1a and H3a, the results support all the hypotheses. The results also reveal that the mediated model explains entrepreneurial intention with a non-negligible R2 value of 0.24 (Table 5, Fig. 2B; Hair et al., 2017), 7% above an unmediated model that does not include the effects of perceived risk and opportunity recognition (R2 = 0.17, Fig. 2A). In terms of Cohen (1988), this mediation effect is weak-to-moderate and significant (f2 = [R2 included - R2 excluded]/ [1- R2 included]; f2 = 0.09). Additionally, the Stone-Geisser blindfolding sample reuse technique –with an omission distance of 9, such that the number of observations in the data set divided by the omission distance was not an integer, as recommended (Ringle et al., 2015), shows Q-square values greater than 0. Thus, the model can be said to effectively predict perceived risk (Q2 = 0.01), opportunity recognition (Q2 = 0.03) and entrepreneurial intention (Q2 = 0.213) (Hair et al., 2017). Furthermore, regarding the out-of-sample predictive power of the model tested for the total sample, with k-folds = 10 and 10 repetitions (Shmueli, Ray, Velasquez-Estrada & Chatla, 2016), the results reveal positive Q2 values for entrepreneurial intention (Q2 = 0.132) and the two mediators, both opportunity recognition (Q2 = 0.030), and perceived risk (Q2 = 0.010). Thus, the error in predicting the results in PLS-SEM is lower than the prediction error of the model using only the mean values, which supports a good predictive performance of our PLS model. This good predictive performance of our model is also supported because the prediction errors (root mean square error, RMSE, and mean absolute error, MAE) for all the indicators of our model were revealed to be lower using PLS than using linear regression modeling, as recommended (Shmueli et al., 2016). Finally, in terms of overall goodness-of-fit (GoF) the SRMR index (standardized root means square residual) yields a value of 0.038, which is far below the 0.08 cut-off (Henseler, 2017). Moreover, the SRMR's 99% bootstrap quantile is 0.040, and is thus higher than the SRMR value, which indicates that the model has a good fit (Hair et al., 2017). Finally, the discrepancy indices dULS (unweighted least squares discrepancy) and dG (geodesic discrepancy) are also below the bootstrap-based 99% percentile (dULS = 0.078 < HI 95 of dULS; dG = 0.019 < HI 95 of dG) (Hair et al., 2017). Overall, the discrepancy between the empirical and the model-implied correlation matrix is non-significant, which suggests there is no reason to reject the model, or, in other words, that the model tested is likely to be true (Henseler, 2017).

5Discussion and conclusionIn explaining entrepreneurial intention, understanding the role of the motivations underlying the desire to start a firm is crucial (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). In this regard, the dichotomous distinction between push and pull factors is an important question (Amit & Muller, 1995; Dawson & Henley, 2012). While both types of motivations are known to inspire a new venture (Dawson & Henley, 2012), pull motivation is usually more important in practice (Staniewski & Awruk, 2015). However, thus far, research on push versus pull motivations has neither investigated nor compared the distinct role of each type of motive in explaining the formation of entrepreneurial intention (see Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010; Giacomin et al., 2011; Ismail, Shamsudin & Chowdhury, 2012). By analyzing the mechanisms that may help explain this relationship (i.e., perceived risk, opportunity recognition), our study is one of the few to shed light on the different effects of each of these motivations (push, pull) in prompting entrepreneurial intention among individuals.

Our results show that while pull factors positively and directly influence entrepreneurial intention, push factors do not. This distinct influence is important as it coincides with previous literature suggesting that pull motivations have a more important role in predicting entrepreneurship (Staniewski & Awruk, 2015). A closer look at the results indicates, however, that, in an unmediated model, push factors do have a significant effect, although, counter to our predictions, this effect is negative. Thus, the non-significant effect we found of push-factors on entrepreneurial intention was, in fact, due to the mediating role of the two perceptual variables we had included in our research; both perceived risk and opportunity recognition appeared to absorb that negative effect. Our results thus show the paths that push and pull factors can take to influence entrepreneurial intention, as described below.

First, we found that push factors have no significant direct impact but do have a negative indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention, either by increasing the perceived risk of creating a firm or by reducing the likelihood of recognizing market opportunities. This finding is in line with the nature of these types of motivations, which involves negative connotations (e.g., unemployment, low family income, frustration with the current situation in life, etc.) that lead individuals to start the venture not because it is their preferred option (van der Zwan et al., 2016) but because they feel pushed to do so. Thus, although push factors can make individuals start their own venture, it is unlikely to occur because they show strong willingness to engage in a venture. In fact, the opposite is true. Push factors will lead individuals to show a lower entrepreneurial intention, through augmenting the risk they perceive in venture creation and through limiting the recognition of market opportunities. Our findings are therefore, in line with, and advance on, previous literature arguing that push-driven individuals may have a lower risk tolerance (Block et al., 2015) and be associated with having less attractive business ideas (van der Zwan et al., 2016). Furthermore, these findings seem to indicate that push factors are more likely to play a significant role in making individuals engage in entrepreneurial action, not in leading them to willingly start a new venture. As documented in previous research, push-individuals start a venture not because it is their preferred option (van der Zwan et al., 2016), but as a means of survival (Eijdenberg & Masurel, 2013). Our findings thus come to confirm previous research as they reveal push factors have a negative impact on an individual's true willingness to start a venture.

Second, only motivators associated with positive connotations, such as pull factors (e.g., need for achievement, independence), were found to help individuals form their entrepreneurial intention. They do so not only directly, but also indirectly. However, in the latter case, this is only via increasing the likelihood of recognizing business opportunities. Indeed, opportunity recognition was found to mediate the positive influence of pull factors, but perceived risk was found not to. The former was found to mediate this relationship in support of extensive literature that indicates pull driven individuals are more willing to express and materialize creativity in life (Hansen et al., 2011), and to envision new, unexploited opportunities (Block et al., 2015; Dawson & Henley, 2012), which, in turn, encourages entrepreneurial intention (Krueger, 2009). Contrary to our predictions, perceived risk failed to mediate the positive relationship between pull factors and entrepreneurial intention. The higher risk-taking that pull motivations entail (Kiggundu, 2002), which was not empirically controlled for, may have nulled the negative effect pull factors were predicted to have on perceived risk. Notwithstanding, market gap identification is inherent to having pull motivations (Williams, 2009), so it would be unsurprising that the indirect effect of pull factors on entrepreneurial intention follows the path led by opportunity recognition as a mediator, in contrast to the path led by perceived risk.

Overall, our findings enhance the current understanding of the role of push versus pull factors on entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, the findings reveal that, rather than having a positive effect, push motivators negatively influence entrepreneurial intention. The higher perceived risk in venture creation and the lower opportunity recognition of push-motivated individuals would be the reasons for such a negative effect. Pull factors, instead, help positively form entrepreneurial intention, mainly through increasing the likelihood of recognizing groundbreaking business opportunities.

5.1Implications for entrepreneurial intention theoryOur findings advance the literature on entrepreneurial intention in several ways. First, this research responds to the call by Carsrud and Brännback (2011) to analyze the influence of motivation on entrepreneurial intention. Several studies have analyzed the important role of push-pull motivations in the decision to engage in entrepreneurial activity (Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010; Giacomin et al., 2011; Ismail et al., 2012). However, most of these studies have investigated the role of these motives among entrepreneurs that have already initiated their venture, not how these motivations can shape entrepreneurial intention as a prior step to becoming an entrepreneur. Our study with undergraduates enabled us to analyze the separate influence of push and pull motivational factors on entrepreneurial intention such that researchers can learn that the motivations to start a new venture, whether pull or push, shape entrepreneurial intention positively or negatively. These motivations are strongly linked to the things that individuals prioritize in their lives (Fayolle et al., 2014). Thus, if they prioritize the things that “venture creation” inherently entails, such as autonomy and challenge (pull motivations), they will be willing to start a venture. However, if they see venture creation as an alternative for earning a living (push factors), individuals will not see it as something they truly value, which may explain the negative indirect effect of push factors on entrepreneurial intention that we found. Thus, our findings advance the literature by confirming previous literature (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Rindova, Barry & Ketchen, 2009) that emphasizes pull factors (e.g., independence, vision, self-realization) as the most significant motivation in being willing to start a venture.

Second, this research advances the emerging call on the need to expand Krueger's Model of Entrepreneurial Intention (Elfving et al., 2017; Krueger, 2009). It does this by incorporating new perceptual variables that are different to those commonly suggested as conductors in the process to explain entrepreneurial intention (perceived feasibility, perceived desirability of venture creation, Krueger et al., 2000) and are more explicative of the environment. Thus, as a novelty in the literature, we modeled and found that perceived risk in venture creation and opportunity recognition, which are closely linked to perceived feasibility and desirability, respectively, can act as mediators in the relationship(s) between push-pull factors and the formation of entrepreneurial intention.

Finally, this research advances the emerging field of study on the need to integrate the existing mainstream models of entrepreneurial intention (Esfandiar et al., 2019). Specifically, based on the cognitive perspective (Ahmad et al., 2014; Baron, 2004), through which potential entrepreneurs’ intentions to create a venture are conceptualized to be influenced by their own perceptions on the external environment, this paper extends the current knowledge on how entrepreneurial intention is formed. In doing so, we integrate Push-Pull Theory (Amit & Muller, 1995) into Krueger's Model (Krueger, 1993; Krueger et al., 2000) and incorporate motivational (push and pull factors) and perceptual variables (perceived risk and opportunity recognition) into a unified model. In this way, the study positions “motivation” in an initial stage of the process, coinciding with the findings of a small number of other studies (Ferri, Ginesti, Spano & Zampella, 2019; Tognazzo et al., 2017), so that the results of this study enable a better understanding of what occurs in the first stages of the process leading to entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, this study helps researchers learn “how” perceived risk and opportunity recognition (perceptual variables) play a specific mediating role between the initial stage (i.e., push–pull motivations) and one of the last stages of the process (i.e., entrepreneurial intention), prior to ultimately leading someone to start a new venture. Moreover, the mediating role of perceived risk and opportunity recognition allows some of the differences found in previous research on push–pull factors to be explained. For example, although research reveals that both factors are positives for self-employment decisions (Dawson & Henley, 2012), pull factors are found to be more important (Eijdenberg & Masurel, 2013). Some studies (i.e., Thurik et al., 2008) even conclude that push-driven individuals are far more likely to be hired by other entrepreneurs than to start a new venture. Thus, by considering these mediators (i.e., perceived risk, opportunity recognition), which provide more information on the environment than other perceptual variables (such as perceived feasibility and desirability), we learn the reasons for the impact of push factors (pull factors) on entrepreneurial intention being negative (positive).

5.2Practical implicationsOur results have several practical implications for entrepreneurship education, public policy and practitioners. First, concerning entrepreneurship education, our results lend support to the notion that professionals should design entrepreneurship courses in such a way that they encourage the internal desire to create a new venture (Jena, 2020). Because pull-related motivations are internal to an individual (i.e., self-realization, personal satisfaction, autonomy, independence, sense of achievement; see Staniewski & Awruk, 2015), emphasizing them is essential to awaken the internal desire to start a new venture. Otherwise, if the message is that starting a new venture is only a good option in cases of unemployment or situational dissatisfaction, interest in starting a venture is likely not to arise, unless such negative external situations irretrievably push one to do so. Thus, by cultivating an internal passion for entrepreneurship, students are more involved in an affective internal state, which releases positive and joyful feelings about entrepreneurial activity, making it part of their own personal identity (Costa et al., 2018). Therefore, beyond in-class training, successful entrepreneurship education should involve experiential and discovery learning. Options for training programs should emphasize “learning-by-doing” (Shirokova et al., 2018) and make students take an active role in creating small ventures on campus and/or participating in courses that use computer-based simulations. With such programs, students might experience some of the positive, affective aspects of creating a new venture (San-Tan & Ng, 2006). These programs should also provide coaching and give feedback during the training session to shape students’ entrepreneurial identity (Nielsen & Gartner, 2017). Importantly, these programs should emphasize interactions with “entrepreneurial” instructors, as such interactions can help transform “hearts and minds” as well as transmit enthusiasm for entrepreneurship, thus leading students to become significantly more entrepreneurial (Sánchez, 2013).

Even when all these training efforts are implemented, a pull-factor motivational pattern might not be shaped in all students, and some students might continue to be push motivated. However, such training efforts might not fall on deaf ears. These educational practices may also serve to augment business opportunity recognition and to reduce risk perceptions associated with venture creation. On the one hand, training programs might encourage students to enjoy positive feelings and relevant entrepreneurial experiences in such a way that they will inspire them to realize the importance of understanding their surroundings in an entrepreneurial manner. As a result, students will become more likely to develop entrepreneurial cognitive structures, such as business opportunity prototypes (Costa et al., 2018). In addition, interactions with agents with entrepreneurial experience should help develop business opportunities (Shirokova et al., 2018). On the other hand, training programs that use real-life designs and successful entrepreneurs as lecturers could help students shape the belief that one is capable of successfully performing the entrepreneur's roles and tasks (Chen, Greene & Crick, 1998), thus helping to associate venture creation with a lower probability of failure and a lower risk (Arenius & Minniti, 2005).

Second, concerning public policy, the results of our study can help public institutions understand that public initiatives will affect entrepreneurial intention only if they are oriented towards stimulating pull motivations and shaping perceptions that are helpful to forge a strong willingness to start a new venture (i.e., reduced levels or risk perceived, recognition of high value-added opportunities in the market). Thus, a first line of action of public institutions or other organizations that support entrepreneurship can be aimed at offering university students (or students of vocational training), who are about to enter the job market (Hattab, 2014), personalized advice and selective training programs. Such programs should allow them, on the one hand, to recognize and enhance their pull motivations, and on the other hand, to ensure they acquire the skills, experience and critical competencies needed to activate the internal desire to create a new venture (Jena, 2020). Another interesting line of action might be for public institutions to design policies and programs oriented towards acting on reducing the level of perceived risk in venture creation and on augmenting opportunity recognition (Sendra-Pons, Comeig & Mas-Tur, 2022). In this regard, public institutions could develop policies and structures aimed at establishing a supportive network formed by consultants, advisors and investors, through which advice and assistance can be offered (Carter et al., 1996). With such a policy, these individuals could be equipped with analytical tools and techniques (e.g., market research, risk analysis; Forlani & Mullins, 2000) with which to reduce the variability of the forecasts of the different scenarios in which their idealized venture may be situated and could thus alleviate their levels of perceived risk of starting a new venture. In addition, with such a policy, these individuals would be provided with social networks through which information pointing to business opportunities could be shared (Arenius & Minniti, 2005; Mira-Solves, Estrada-Cruz & Gomez-Gras, 2021), thus helping to activate their recognition of potential market opportunities in the market.

Finally, our research also has important implications for practitioners. Through our results, consultants, advisors, and entrepreneurs themselves can benefit from a better understanding of how intentions are formed and how motives and perceptions come together to promote willingness to start a new business. Furthermore, nascent entrepreneurs or entrepreneurs of new and/or established business can understand why they made certain decisions at the time of starting their venture, which, according to Krueger et al. (2000), is likely to help them in their future business decisions.

In addition, the findings of the current investigation can be especially relevant in the case of businesses wishing to implement an organizational culture that supports entrepreneurial activity. First, businesses should foster an organizational culture in which organizational members can learn about the positive aspects of developing business ideas as well as of undertaking such ideas, among which are “being independent or autonomous of their current employer”. It is also essential these businesses develop an entrepreneurial culture consisting of the development of structures, policies and supportive mechanisms that collectively reinforce values and norms favorable to entrepreneurship (Freytag & Thurik, 2010). Specifically, through building an entrepreneurial culture, employees can reduce their perceived risk in venture creation because such a culture could lead them to be aware that obstacles to start a new line of business are surmountable –thanks to the support provided by their current employer and other members of the business– and that failure is acceptable and part of an entrepreneurial progress that is slow but steady (Malebana, 2014). Similarly, through this culture, employees can be provided with information and resources on various opportunities to develop and expand their current business, which can channel their entrepreneurial spirit via recognizing business opportunities (Freytag & Thurik, 2010).

5.3Limitations and future research directionsAlthough our study contributes several new insights to the entrepreneurship literature, it is not without limitations. For example, we used cross-sectional data, so our results cannot provide strong causal inferences. However, a proven theory such as TPB (Ajzen, 1991) suggests that causality goes from attitudes to intentions, and the intuition suggests that entrepreneurs create their ventures because they have the motivation to do so, and not the other way around (Collins et al., 2004). Nevertheless, we recommend further longitudinal studies to address our causality inferences with greater precision.

Another limitation is the self-reported nature of our data, which can lead to problems of subjectivity that bias the findings. For example, individuals might not recognize their true motivations for having started a business, and some of these motivations (i.e., push) may have been strongly influenced by an external situation (Staniewski & Awruk, 2015; van der Zwan et al., 2016). For example, push motivations might be important in starting a new venture if respondents are going through a difficult period (i.e., a bad situation in the labor market, lack of interesting offers and positions; Staniewski & Awruk, 2015), which is not a common occurrence among young undergraduates (Segal et al., 2005). Thus, future research could include a more varied sample in terms of age segments while also using other methods to measure the variables more objectively.

Our conclusions are also limited by the cultural context of the study (Spain), as this factor influences the degree to which certain entrepreneurial aspects (i.e., independence, risk-taking) are desirable in a society (Shirokova et al., 2018). Thus, because venture creation involves risk and uncertainty (Sánchez, 2013), our findings might be more applicable in countries which, like Spain, show high levels of uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede Center, 1967–2010). We thus recommend future works replicate our study in other cultures to improve the external validity and generalizability of the research.