The correct management of reputation and image can be crucial to guarantee organizationś survival and success. However, the lack of clarity regarding the relationship and differences between image and reputation still exist since scholars have considered them related constructs with differences and used them interchangeably. Spanish Public Universities operate in a highly competitive sector where factors such as globalization as well as the decrease in government funding have strengthen this situation. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to measure the relationship between image and reputation in the context of Spanish Public Universities considering different university's stakeholder perceptions (students, alumni, professors, support personnel and managers). To pursue this objective, a review of literature on image and reputation was developed, followed by the distribution of 870 surveys to a Spanish Public University's stakeholders. Finally, PLS-SEM was used to analyse the data and confirm the existing relationship between image and reputation.

The higher education sector has been experimenting a consistent increase in its competition levels (Lafuente-Ruiz-de-Sabando, Zorrilla, & Forcada, 2017). Factors such as globalization, degree of internationalization, changes in the market as well as reduction in government funding have enhanced this situation (Hemsley-Brown, Melewar, Nguyen, & Wilson, 2016; Verčič, Verčič, & Žnidar, 2016).

Universities are no longer untouchable entities that could assume that society would trust them without being questioned (Verčič et al., 2016). Stakeholders are sceptical due to the efforts that universities are putting on research instead of teaching as well as due to the lack of effort to serve the public in the correct manner (Phair, 1992).

Under these circumstances, universities have understood that the correct management of intangible assets such as image and reputation is a key element for attracting and retaining stakeholders (Hemsley-Brown et al., 2016; Plewa, Ho, Conduit, & Karpen, 2016).

Reputation and image have been considered crucial resources for the survival and success of organizations (Gray & Balmer, 1998). Both variables will affect the evaluation that stakeholders make about organizations (Czinkota, Kaufmann, & Basile, 2014; Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, 2000; Gotsi & Wilson, 2001) since their perceptions of quality will increase. Due to their relevance, numerous scholars have developed research on these constructs, however, there is still lack of clarity between the differences and relationships between both, since some authors have used them as synonymous or interchangeably (Furman, 2010), while others have highlighted their differences but considering them as related constructs (Rindova, Williamson, Petkova, & Sever, 2005; Zineldin, Akdag, & Vasicheva, 2011).

The aim of this paper is, first, to understand through a theoretical framework the relevance of image and reputation in the higher education context. Second, to identify the main differences, common traits as well as relationships between the given constructs. Furthermore, to verify if the selected measurement scales used to measure image and reputation as multidimensional constructs are supported through this research. And finally, to empirically demonstrate the relationship between image and reputation in the Spanish Public Universitieś context. This evaluation will be made considering different stakeholders (students, professors, support personnel, managers and alumni) perceptions. To follow this objective, we will review the literature on image and reputation within the higher education sector. Following this, a Spanish Public University will be analysed as the sample where surveys will be made to measure the different stakeholders’ perceptions.

2Theoretical framework2.1Image in the higher education sectorWhen evaluating an organization, corporate image represents a sign of quality and has the ability to affect the degree of customers loyalty and stakeholders decision rules (Fornell & Dekimpe, 2010; Nguyen & LeBlanc, 2001). In addition, the relationship with stakeholders can be improved as well as the corporate reputation of the organization (Tran, Nguyen, Melewar, & Bodoh, 2015).

In the higher education sector, competition to attract resources, students and professors has expanded to international levels (Altbach, Reisberg, & Rumbley, 2010) and the decrease in government funding has contributed to the development of private institutions in the sector (Lafuente-Ruiz-de-Sabando et al., 2017).

Higher education institutions have understood the importance of managing intangible assets such as image to differentiate themselves over competitors and to improve the relationship with their stakeholders (Nguyen & LeBlanc, 2001).

Universities are assigning more resources to manage their image and improve it in society's and stakeholders eyes (Curtis, Abratt, & Minor, 2009) since in the higher education sector, intangible perceptions could be more relevant than measurable substances for stakeholders decisions.

Additional problems that higher education institutions have been facing over the years relate to stakeholders and society's perceptions that universities efforts focus on research instead of teaching. The issues of how these institutions handle money and the lack of efforts to serve the public in the correct manner has also been a problematic area (Khurana & Nohria, 2008; Phair, 1992). Therefore, due to the crisis of trust, the need to regain public trust through intangible assetś management and correct communication with the different stakeholders in their environment increases its importance.

Despite the relevance that holding a positive image has for higher education institutions, there is still lack of empirical research to understand in a deeper degree which elements and strategies might be crucial to manage it in an efficient manner (Duarte, Alves, & Raposo, 2010; Wilkins & Huisman, 2015).

University's image has been defined in several ways, Alessandri, Yang, and Kinsey (2006, p. 259) considered it as “the public's perception of the university”. Other authors, as “the sum of all beliefs an individual has towards the university” (Duarte et al., 2010, p. 23). Arpan, Raney, and Zivnuska (2003, p. 100) defined image in the higher education context as “various beliefs about a university that contribute to an overall evaluation of the university”.

Image is considered a multidimensional and formative construct in the higher education context (Lafuente-Ruiz-de-Sabando et al., 2017). Despite the lack of agreement of its dimensions, scholars have tried to clarify this aspect. Beerli Palacio, Díaz Meneses, and Pérez Pérez (2002) identified two university's image components, the cognitive and affective dimension. Also, Kazoleas, Kim, and Anne Moffitt (2001) analysed the organizational, personal and environmental factors that affected the university's image perception.

2.2Reputation in the higher education sectorCorporate reputation has been considered as a valuable intangible asset for organizations due to its relationship with positive performance (Rindova et al., 2005). Researchers believe that reputation affect the evaluations that stakeholders make about organizations (Czinkota et al., 2014; Fombrun et al., 2000; Gotsi & Wilson, 2001).

Universities operate in a highly complex environment, competing for economic resources from the government as well as for talented students, prestigious professors and competent employees internationally (Christensen & Gornitzka, 2017; Hemsley-Brown et al., 2016; Plewa et al., 2016; Verčič et al., 2016). Furthermore, despite the existing criticism (Barron, 2017), stakeholders and society's expectations regarding the scores hold by universities in quality and employability rankings are increasing, augmenting the pressure for these organizations.

Moreover, currently universities need to focus, not only on professors or a unique interest group, but on numerous groups of stakeholders whose support is a key element for their success and survival (Christensen & Gornitzka, 2017).

Under this scenario, institutions in the higher education sector have been adopting more business-like practice in their management (Veloutsou, Paton, & Lewis, 2005) and a more market-orientated approach.

The literature has shown that favourable reputation has many benefits for organizations, and in the higher education sector, due to its intangible nature and the fact that its quality might be difficult to evaluate before it is experienced (Suomi, 2014) reputation will serve as a quality sign, and therefore, will reduce uncertainty for stakeholders in their decision-making processes (Hemsley-Brown, 2012).

However, despite the importance of achieving and maintaining a good reputation towards the different institution's stakeholders, there is still lack of clarity on its management and it continues to be a challenge for universities (Vidaver-Cohen, 2007) since empirical investigations are still limited (Volkwein & Sweitzer, 2006; Watkins & Gonzenbach, 2013).

Some researchers have tried to find a more accurate definition of concept within the academic field, such as, Šontaitė and Bakanauskas (2011) which defined it as a subjective and collective recognition and evaluation of among all stakeholder groups during a specific period, influenced by their past behaviour, communication and potential to satisfy expectations in comparison with rivals. Other authors such as Alessandri et al. (2006, p. 261) offered the following definition of reputation: it is “the collective representations that the university's multiple constituents hold of the university over time”.

Despite there being many factors affecting reputation in the academic field, faculty and students conditions such as salaries and graduation rates appear as relevant in the literature (Volkwein & Sweitzer, 2006). Some of the other dimensions that were identified in the literature were the quality of academic performance, quality of external performance and emotional engagement (Alessandri et al., 2006); leadership, teaching, research, the service offered and quality (Brewer & Zhao, 2010). In trying to identify the determinants and antecedents of reputation in the academic context, Vidaver-Cohen (2007) developed a conceptual model to measure reputation in the business school field. Suomi (2014) performed a study to identify the dimensions that form reputation in a master's degree program through the application of the conceptual model developed by Vidaver-Cohen (2007) and including a variety of internal and external stakeholder groups.

2.3Relationships and differences between image and reputationWhen analysing the relationship and differences between corporate image and reputation, there is no consensus on how to use each construct. Gotsi and Wilson (2001) consider that the different nature of both constructs has received more support in terms of the references. Some scholars have used them as synonymous (Furman, 2010) while others such as Gotsi and Wilson (2001) have treated both variables as completely independent concepts. Furthermore, in the attempt to clarify the confusion, image and reputation have been also found to be different but related concepts in the literature (Zineldin et al., 2011). Due to this situation, researchers face the challenge to clarify this matter and define how image and reputation differ and relate (Gotsi & Wilson, 2001).

Within the literature several common traits shared between image and reputation have been identified. Both variables can be considered as crucial strategic assets for organization's survival and competitive position in the market (Gray & Balmer, 1998), and both consider what external stakeholders perceive about the organization (Nguyen & LeBlanc, 2001).

Many scholars have tried to differentiate image and reputation according to several characteristics. Reputation is the result of a consistent behaviour, whereas image is managed and modified in an easier manner through communication campaigns (Gray & Balmer, 1998). Many scholars have highlighted as a relevant difference the temporality (Smaiziene & Jucevicius, 2009), since reputation can be the result of maintaining a consistent image over time, while image can be created in a shorter period of time and it is easier to change (Smaiziene et al., 2009).

However, despite the clear differences between image and reputation, most of the work developed by scholars agrees on the fact that both variables are different but related.

The images held by different stakeholder groups will result in the organization's reputation over a longer period of time (Fombrun & Van Riel, 1997). Therefore, reputation will be the result of being able to maintain a strong image over time, so image will affect reputation (Gray & Balmer, 1998; Tran et al., 2015). Tran et al. (2015) defined corporate image as the tangible and intangible aspects interconnected with reputation. Other authors have considered that better corporate image results in a better reputation (Fornell, Rust, & Dekimpe, 2010). Therefore, corporate reputation could be understood as the result and final outcome of building and maintaining corporate image since an organization's reputation is shaped by the images of the given institution (Harvey, Morris, & Müller Santos, 2017).

In conclusion, maintaining a corporate image will move in a deeper manner into stakeholderś minds and will shift from superficial awareness to deeper aspects such as favourability which is similar to aspects related to how corporate reputation is formed (Worcester, 2009). Podnar and Golob (2017) supported the idea of the dependence that an entity's reputation has on the day-to day-images held by its stakeholders and argues the need of additional research on the relationships and differences between image and reputation in order to clarify this matter.

Based on the literature review on the manner in which image and reputation relate, the following hypothesis is proposed:Hypothesis 1 Image is an antecedent of reputation

The selected research setting was the Spanish Public Universities, since at it is happening in the different countries, these institutions need to identify the best manner to manage their intangible assets to improve their situation in their sector. Spanish Public Universities are reducing their number of students in favour of private ones, since government funding has been decreasing. In fact, since 2001, fourteen private universities have been created within the Spanish higher education sector (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2018). Within the Spanish Public Universities, Rey Juan Carlos University of Madrid has been the chosen one to develop the analysis of this paper, where information from different stakeholders (professors, students and alumni, administrative personnel and managers) was gathered. Rey Juan Carlos University is a Public University which started its active 20 years ago and currently has 38.085 students and 1.543 professors. Regarding the position that the given university holds in some of the most prestigious national rankings, it currently appears in the 7th position in the U-Ranking (2018).

For collecting the data, an online questionnaire where developed. On an initial stage, a pre-test was developed with 300 students to verify the scale used and to adapt the questions of the survey if it was necessary. In the final stage, a total number of 844 effective surveys were answered, were 73% were students, 0.6% alumni, 16% professors, 0.3% administrative personnel and 0.1% managers.

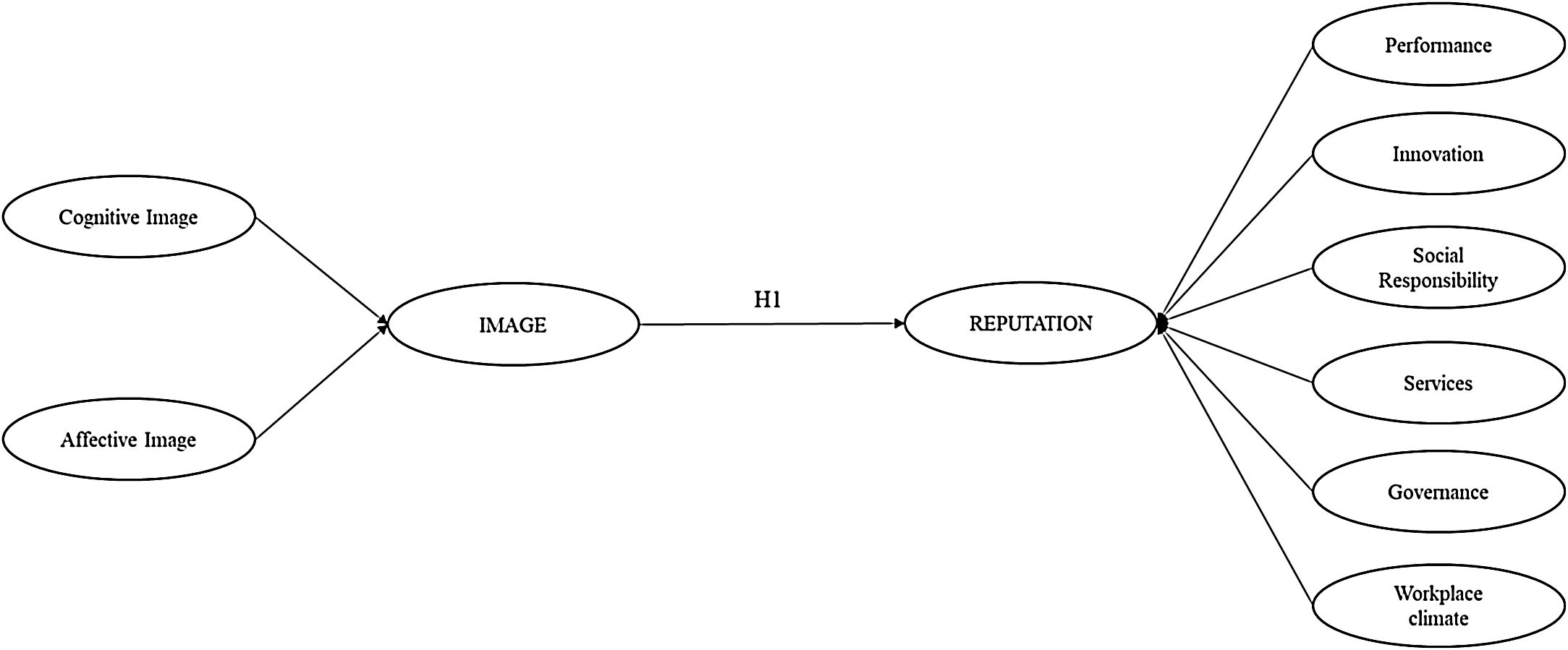

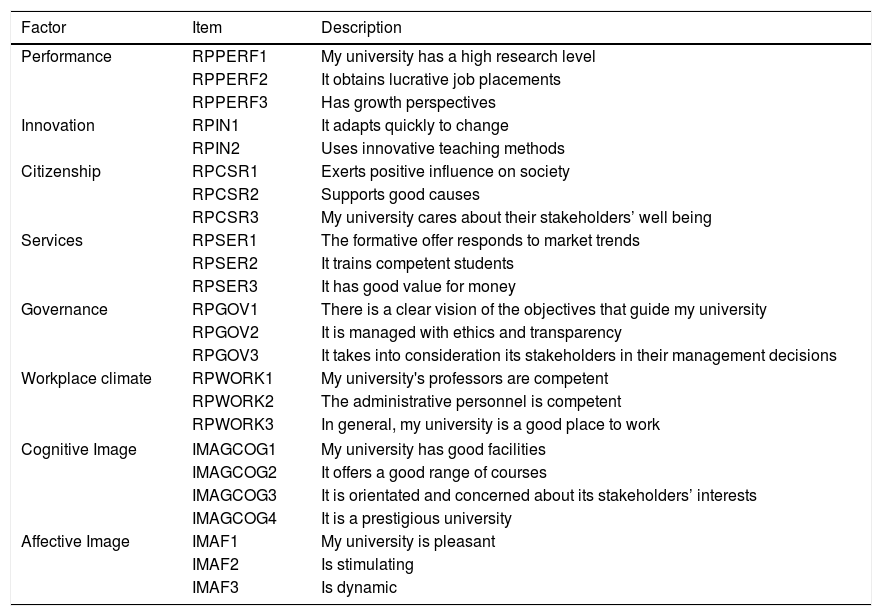

All constructs were measured through adapted items from existing scales and used a 10 points Likert scale. The items used to measure reputation were taken from Vidaver-Cohen (2007). Her measurement model considered reputation as a multidimensional variable and included the following dimensions: performance, innovation, services, governance, citizenship and workplace climate. In the case of the items used to measure image they were taken from Beerli Palacio et al. (2002). In their research, they viewed image as a two-dimension construct including several items to measure the affective and the cognitive component. Both image and reputation have been considered as formative constructs for this research since the constructs are considered as the aggregation of all their indicators (Helm, 2007), where the latter causes the latent variable (Diamantopoulos, Riefler, & Roth, 2008). In fact, many authors such as Schwaiger (2004) or Helm (2011) have considered intangible assets as formative constructs. Table 1 presents the model.

Measurement model.

| Factor | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | RPPERF1 | My university has a high research level |

| RPPERF2 | It obtains lucrative job placements | |

| RPPERF3 | Has growth perspectives | |

| Innovation | RPIN1 | It adapts quickly to change |

| RPIN2 | Uses innovative teaching methods | |

| Citizenship | RPCSR1 | Exerts positive influence on society |

| RPCSR2 | Supports good causes | |

| RPCSR3 | My university cares about their stakeholders’ well being | |

| Services | RPSER1 | The formative offer responds to market trends |

| RPSER2 | It trains competent students | |

| RPSER3 | It has good value for money | |

| Governance | RPGOV1 | There is a clear vision of the objectives that guide my university |

| RPGOV2 | It is managed with ethics and transparency | |

| RPGOV3 | It takes into consideration its stakeholders in their management decisions | |

| Workplace climate | RPWORK1 | My university's professors are competent |

| RPWORK2 | The administrative personnel is competent | |

| RPWORK3 | In general, my university is a good place to work | |

| Cognitive Image | IMAGCOG1 | My university has good facilities |

| IMAGCOG2 | It offers a good range of courses | |

| IMAGCOG3 | It is orientated and concerned about its stakeholders’ interests | |

| IMAGCOG4 | It is a prestigious university | |

| Affective Image | IMAF1 | My university is pleasant |

| IMAF2 | Is stimulating | |

| IMAF3 | Is dynamic | |

In order to analyse the established hypothesis and relationships structural modelling with SmartPLS system version 3 was used. This technique was chosen because it presents adequate advantages for the research to be carried out (Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins, & Kuppelwieser, 2014).

First of all, the global goodness of the model was tested for the estimated model following Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016) considering the SRMR, the bootsrap quartile of SRMR, unweigthed least squares discrepancy (Duls) and the geodesic discrepacny (Dg). The obtained results show that the model fulfils the criteria of SRMR<0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) since the SRMR was 0.013, however, the criteria of goodness-of-fit tests based on bootsrap was not accomplished. For the estimated model the following results were reached (SRMR>HI95 of SRMR, SRMR= 0.013, HI95 of SRMR=0.005; Dg>HI95 of Dg, Dg=0.021, HI95 of Dg=0.004; Duls>HI95 of Duls, Duls=0.006; HI95 of Duls=0.001). However, authors such as Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, and Gudergan (2017) as well as the authors of the exact model fit (bootstrapping) consider that the exisiting PLS-SEM literature on exact fit measures as well as its application is still on a priliminar stage (SmartPLS, 2018), therefore it can be considered that the obtained results do not affect the validity of the model for this research.

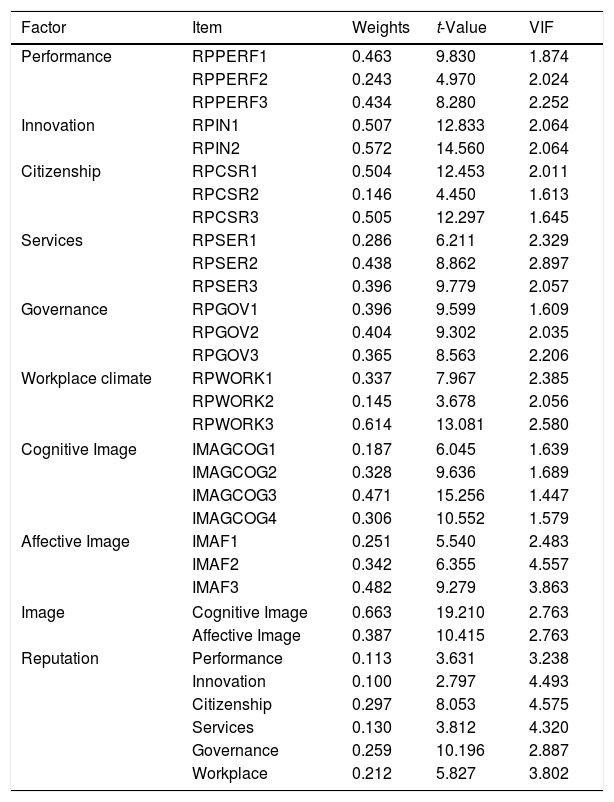

The next step carried out when managing the data was to verify the reliability and validity of the measurement model shown in Fig. 1. In Table 2 the information regarding the model's reliability and validity is presented. For both reputation and image constructs, the collinearity (VIF) value is presented, showing that every item is under the appropriate level of VIF<5 (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011). In addition, the standardized weights are shown in both tables as well as their significant values (p<0.01), showing that all formative values affect in a significant manner to their dimensions or construct in the case of the second-order. The results show that the six dimensions of reputation affect in a significant manner to the overall construct (p<0.01), however, aspects such as citizenship and governance represent higher values when compared to the rest of the dimensions. In the case of image, both the cognitive and affective dimensions are significant (p<0.01), and the cognitive component's weight is higher than the affective one.

Measurement model reliability and validity.

| Factor | Item | Weights | t-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | RPPERF1 | 0.463 | 9.830 | 1.874 |

| RPPERF2 | 0.243 | 4.970 | 2.024 | |

| RPPERF3 | 0.434 | 8.280 | 2.252 | |

| Innovation | RPIN1 | 0.507 | 12.833 | 2.064 |

| RPIN2 | 0.572 | 14.560 | 2.064 | |

| Citizenship | RPCSR1 | 0.504 | 12.453 | 2.011 |

| RPCSR2 | 0.146 | 4.450 | 1.613 | |

| RPCSR3 | 0.505 | 12.297 | 1.645 | |

| Services | RPSER1 | 0.286 | 6.211 | 2.329 |

| RPSER2 | 0.438 | 8.862 | 2.897 | |

| RPSER3 | 0.396 | 9.779 | 2.057 | |

| Governance | RPGOV1 | 0.396 | 9.599 | 1.609 |

| RPGOV2 | 0.404 | 9.302 | 2.035 | |

| RPGOV3 | 0.365 | 8.563 | 2.206 | |

| Workplace climate | RPWORK1 | 0.337 | 7.967 | 2.385 |

| RPWORK2 | 0.145 | 3.678 | 2.056 | |

| RPWORK3 | 0.614 | 13.081 | 2.580 | |

| Cognitive Image | IMAGCOG1 | 0.187 | 6.045 | 1.639 |

| IMAGCOG2 | 0.328 | 9.636 | 1.689 | |

| IMAGCOG3 | 0.471 | 15.256 | 1.447 | |

| IMAGCOG4 | 0.306 | 10.552 | 1.579 | |

| Affective Image | IMAF1 | 0.251 | 5.540 | 2.483 |

| IMAF2 | 0.342 | 6.355 | 4.557 | |

| IMAF3 | 0.482 | 9.279 | 3.863 | |

| Image | Cognitive Image | 0.663 | 19.210 | 2.763 |

| Affective Image | 0.387 | 10.415 | 2.763 | |

| Reputation | Performance | 0.113 | 3.631 | 3.238 |

| Innovation | 0.100 | 2.797 | 4.493 | |

| Citizenship | 0.297 | 8.053 | 4.575 | |

| Services | 0.130 | 3.812 | 4.320 | |

| Governance | 0.259 | 10.196 | 2.887 | |

| Workplace | 0.212 | 5.827 | 3.802 | |

Under these circumstances, it was concluded that the proposed model offered appropriate evidence of collinearity and weight-loading relationship and significant levels.

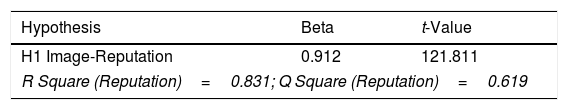

The obtained results through the model show that image positively and significantly affect reputation (H1; B=0.912; p<0.01), therefore the hypothesis established through the literature review can be confirmed. Table 3 shows the results.

5Conclusion and discussionHigher education institutions have understood that holding a positive image and reputation can improve their competitive position, help them to regain public trust and could serve as a quality sign (Nguyen & LeBlanc, 2001), since it will reduce uncertainty (Rindova et al., 2005) for stakeholders in their decision-making processes (Hemsley-Brown, 2012). Furthermore, despite the existing literature on the importance that image, and reputation have for organizations, there is still lack of empirical evidence to clarify the differences, common points as well as the relationships between these two variables.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to improve the existing empirical evidence on measuring the relationship between image and reputation and to test the proposed hypothesis on the influence that image has on reputation. This hypothesis was tested on the higher education field, and more precisely on a Spanish Public University due to the lack of empirical research on this field and due to the importance of managing intangible assets in this sector to overcome the complex situation faced by universities. Our results confirmed the proposed hypothesis since image has a positive and significant effect over reputation. This conclusion was already supported by authors such as Zineldin et al. (2011), Rindova et al. (2005), Fombrun and Van Riel (1997), Tran et al. (2015), Gray and Balmer (1998), among others, who have supported de the effect that image has on reputation for organizations.

In addition, when analyzing the different dimensions considered for the measurement of image and reputation the following arguments could be highlighted. In the case of image, both the cognitive and affective components are significant, therefore, the proposed model developed by Beerli Palacio et al. (2002) could be confirmed through this research. Regarding the used model for reputation, the six dimensions proposed by Vidaver-Cohen (2007) also appear as significant, supporting the multidimensional character of the construct.

The relevance of these findings lies, first of all, on offering additional empirical evidence on the relationships between image and reputation. Moreover, an additional matter, are the implications that these results can have on the strategies that universities’ managers apply when managing these intangible assets. Knowing that image has a positive and significant effect on reputation will allow universities’ managers to understand that an action or strategy to increase their university's image can have a positive effect on their reputation. Therefore, they could benefit from synergies and reduce costs when managing these assets.

Within the limitations and future research lines, two main points could be highlighted. First of all, the sample was a unique Spanish Public University, where even though the size of the sample was wide enough, a deeper understanding could be reached through an analysis of a higher number of universities. Second, for this work, despite the fact that different stakeholders were considered, the differences between the perceptions of each of these groups was not analysed. Therefore, the future research lines regarding the analysis of the relationships between image and reputation in the Spanish higher education context relate to meeting these two points: consider a higher number of public universities as the sample and make a comparison of the obtained results by stakeholder group.