Drawing on the theory of threatened egotism, this study hypothesized that organization-based self-esteem moderates the negative relationship between abusive supervision and affective organizational commitment, as well as the positive relationships between abusive supervision and intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. A two-wave survey was used to collect data from 284 employees nested within 55 organizations. The results of HLM analyses supported this study's hypothesized model. Specifically, organization-based self-esteem moderated all the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes in this study in such a way that the relationships were stronger for employees who were higher rather than lower in organization-based self-esteem. The implications pertaining to practice and theory are discussed.

Tepper (2000) defined abusive supervision as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (p. 178). Abusive supervision is viewed as a dysfunctional (Xu et al., 2015) or destructive (Emmerling et al., 2023) leadership behavior because it leads to increased workplace deviance (e.g., Watkins et al., 2019), decreased positive job attitudes (e.g., Smith et al., 2022), and increased intentions to quit (e.g., Jain et al., 2023). The negative norm of reciprocity postulates that unfavorable treatment induces retaliation (Gouldner, 1960). Employees are likely to equate their supervisors’ behaviors with the behaviors of the organization (Levinson, 1965). Therefore, abused employees retaliate against both the abusive supervisor and the organization, for example, by engaging in both supervisor-directed and organizational deviance.

Based on behavioral plasticity theory (Brockner, 1983), Schaubhut et al. (2004) hypothesized that global self-esteem will moderate the positive relationships of abusive supervision with interpersonal and organizational deviance so that the positive relationships will be stronger for individuals low in global self-esteem. However, their results showed an opposite moderating effect, revealing that these positive relationships are stronger when individuals’ global self-esteem is higher rather than lower. Accordingly, behavioral plasticity theory (Brockner, 1983) may not appropriately interpret the moderating effects of global self-esteem on the positive relationships between abusive supervision and workplace deviance. Burton et al. (2011) considered several conflicting theoretical perspectives, including threatened egotism, to evaluate the moderating role of self-esteem in individuals’ decision to react aggressively when confronted with abusive supervision. However, they argued that the research setting would influence individuals’ decisions to take aggressive reactions when facing abusive supervision. They found that using scenarios, the positive relationship between abusive supervision and expressions of hostility is stronger for individuals with high rather than low global self-esteem; however, their field study revealed that this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with low rather than high global self-esteem. In addition, Wang et al. (2016) proposed that self-esteem will moderate the positive relationship between abusive supervision and intentions to quit while accounting for threatened egotism and conservation of resources theory. They revealed that this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with high rather than low global self-esteem.

Furthermore, consistent with the theory of behavioral plasticity (Brockner, 1988), Ahmad and Begum (2023) found that organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion, and this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with low rather than high OBSE. Additionally, based on self-verification theory (Swann, 1983), Smith et al. (2022) reported that work-specific self-worth moderates the negative relationships of abusive supervision with job satisfaction and leader satisfaction, and these negative relationships are stronger for individuals with higher levels of work-specific self-worth.

Although several studies have examined the moderating effects of self-esteem on the relationships between abusive supervision and employees’ work outcomes, some research gaps in prior studies have been noted. First, most previous studies have used global self-esteem (e.g., Burton et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016) to test the moderating effects of self-esteem on the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes. However, as Pierce et al. (1989) suggested, organization-specific self-esteem (e.g., OBSE) should predict organization-associated phenomena more accurately than global self-esteem. Surprisingly, to our knowledge, only Ahmad and Begum (2023) used OBSE rather than global self-esteem to examine self-esteem's moderating effect on the abusive supervision-emotional exhaustion relationship. Second, the findings on the moderating effects of self-esteem on the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes are inconsistent; for example, Burton et al. (2011) and Wang et al. (2016) reported opposite results of their field studies examining the moderating effects of global self-esteem. Third, no previous studies have used just one theoretical framework to clearly explain and simultaneously test the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes of affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. Therefore, the underlying theory that could support the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and these work outcomes has never been explored and examined. To fill this theoretical gap and other research gaps in the previous literature mentioned above, we used OBSE rather than global self-esteem to accurately examine self-esteem's moderating effects on the relationships between abusive supervision and these work outcomes. To enhance the generalizability of the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships of abusive supervision with work outcomes, we tested four important work outcomes within one study (Lin et al., 2013). Moreover, we used one theoretical framework, the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996), to clearly explain why employees with high rather than low OBSE are more likely to retaliate more fiercely against their abusive supervisor and employing organization when confronted with abusive supervision.

OBSE is organization members’ evaluation of their values within their employing organization (Pierce et al., 1989). High-OBSE employees are more likely than low-OBSE employees to perceive that they are valuable, important, and competent organization members. However, abusive supervisory behaviors, such as calling an employee incompetent, dispute high-OBSE employees’ favorable self-evaluation of their worthiness and competence. Baumeister et al. (1996) defined threatened egotism as “highly favorable views of self that are disputed by some person or circumstance” (p. 5). In addition, the theory of threatened egotism suggests that individuals with threatened egotism tend to become more aggressive and defensive (Baumeister et al., 1996). Therefore, abused high-OBSE employees are more likely than their low-OBSE counterparts to perceive threatened egotism and subsequently retaliate against the abusive supervisor and the organization (Baumeister et al., 1993; Baumeister et al., 1996). As low-OBSE employees already tend to have negative self-appraisals, abused high-OBSE employees should be more likely to perceive threatened egotism. Consequently, based on the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996), it is reasonable to expect a moderating effect of OBSE on the negative relationship of abusive supervision with affective organizational commitment and on the positive relationships of abusive supervision with intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. Accordingly, abused high-OBSE employees would be expected to be less attached to the organization and engage in more workplace deviance to retaliate against the supervisor and organization. In other words, the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes examined in this study should be stronger when employees’ OBSE is high.

Prior studies have indicated that several management practices could enhance employees' OBSE, such as empowering leadership (Kwan et al., 2022) and procedural justice (Kim et al., 2021). Therefore, without the knowledge of the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships of abusive supervision with affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance, in modern organizational contexts, organizations generally tend to make efforts, e.g., empowering leadership and procedural justice, to enhance employees’ OBSE because OBSE has been found to be positively related to favorable work outcomes. For example, Huang et al. (2024) revealed that OBSE is positively associated with job performance. Liao et al. (2023) indicated that OBSE is positively related to innovative behavior and organizational citizenship behavior-altruism. These favorable work outcomes are essential for contemporary workplaces. For example, employees’ innovative behavior is positively related to the innovation performance of organizations (Chen et al., 2018). Furthermore, Wang and Dass (2017) showed that innovation performance is positively associated with organizational performance.

However, based on the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996), high-OBSE employees, unlike their low-OBSE counterparts, may engage in more deviant behaviors to retaliate against abusive supervisors and employing organizations when experiencing abusive supervision. Therefore, to effectively increase employees’ favorable work outcomes, e.g., affective organizational commitment, and reduce unfavorable work outcomes, e.g., supervisor-directed deviance, it is important to clarify the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes studied in this research. Nevertheless, these moderating effects have never been explored and tested. Compared to the theory of behavioral plasticity (Brockner, 1983), which posits that compared to high self-esteem individuals, low self-esteem individuals will react more strongly to unfavorable role conditions, such as role ambiguity and role conflict, the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) should explain these moderating effects better because abusive supervision is associated with employees’ threatened egotism. Accordingly, based on the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996), this study aimed to explore and test these moderating effects. Managers could consider both employees’ OBSE and abusive supervision and utilize the knowledge of the proposed moderating effects to enhance employees’ affective organizational commitment and reduce employees’ intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance.

Academics and practitioners should understand why and how OBSE moderates the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes. For instance, such moderating effects may support using the theory of threatened egotism to interpret and predict employees’ responses to abusive supervision. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the theory and empirically examine the moderating effects of OBSE on the negative association of abusive supervision with affective organizational commitment and the positive associations of abusive supervision with intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. We expected these abusive supervision-work outcome relationships to be stronger for individuals with higher rather than lower OBSE.

This study contributes significantly to theory and practice. Theoretically, to enhance the generalizability and credibility of the moderating effects of OBSE on the abusive supervision-work outcome relationships, this study was the first to use the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) to explore why high-OBSE as opposed to low-OBSE employees tend to respond more strongly to confronting abusive supervision and how it affects multiple important work outcomes, affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. This study was the first study to explore, test, and confirm that the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) is the underlying theory to appropriately interpret OBSE's moderating effects on the associations of abusive supervision with the work outcomes studied in this research. Moreover, considering managerial implications, this study used OBSE rather than global self-esteem to estimate the self-esteem's moderating effects on the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes more accurately. This would help organizations improve the management practices they implement to deal with employees’ retaliations against their supervisor and the employing organization by delicately accounting for the effects of both abusive supervision and individuals’ differences in OBSE.

Affective organizational commitment is “employees’ emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in, the organization” (Allen & Meyer, 1990, p. 1). Tepper et al. (2009) defined intentions to quit as an employee's subjective thoughts about permanently leaving his or her employing organization in the near future and looking for new employment. Workplace deviance refers to employees’ intended behaviors that violate organizational norms and purposefully harm the organization and/or its members (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). Supervisor-directed deviance is directed against an immediate supervisor, whereas organizational deviance is directed against a company (Gauglitz & Schyns, 2024; Tepper et al., 2009). This study examined not only employees’ deviant behaviors but also their job attitudes. These employees’ work outcomes are important for organizations. For example, deviant behaviors threaten the employing organization's revenue; for instance, theft annually costs an estimated $40 to $120 billion (Bennett & Robinson, 2000).

2Literature review and hypothesesIn the following two sections, we first discuss the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes. We then speculate why high-OBSE employees are more likely to retaliate against the abusive supervisor and the organization when they confront abusive supervision compared to their low-OBSE counterparts.

2.1Abusive supervision and work outcomesThe social exchange rules between supervisor and subordinate involve positive and negative norms of reciprocity. The former is the exchange of benefits, whereas the latter is the exchange of injuries (Gouldner, 1960; Uhl-Bien & Maslyn, 2003). For example, a supervisor may promote a subordinate in return for his or her good performance. On the other hand, abused subordinates would retaliate against the source of the abuse, i.e., the supervisor, by engaging in supervisor-directed deviance. However, because supervisors represent their organization and need to motivate and communicate with subordinates to achieve organizational goals, subordinates tend to conflate their supervisors’ conduct with that of the organization (Levinson, 1965). Therefore, abused subordinates would hold the organization responsible for the supervisor's actions. Accordingly, the organization should establish policies and make efforts to reduce abusive supervision. Under these circumstances, abused employees may believe that the organization does not care about their well-being and, consequently, may be less likely to develop an attachment to that organization. Similarly, abused subordinates are more likely to intend to quit the employing organization and less likely to feel an affective commitment to it (Tepper et al., 2008). In addition, based on the negative norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960) and the notion that an organization should be responsible for the abusive supervisor, abused subordinates would retaliate against the employer by engaging in more organizational deviance.

The literature indicates that abusive supervision is negatively related to affective organizational commitment (e.g., Tepper et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2016) and positively related to intentions to quit (e.g., Jain et al., 2023; Srivastava et al., 2022; Vogel & Mitchell, 2017), supervisor-directed deviance (e.g., Gauglitz et al., 2023; Kluemper et al., 2019; Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007), and organizational deviance (e.g., Kluemper et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021). Based on these theories and empirical findings, the victims of abusive supervision would retaliate against their supervisor through supervisor-directed deviance and against their employer by reducing their affective organizational commitment, increasing their intention to quit, and engaging in organizational deviance.

The direct relationships of abusive supervision with affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance have been extensively tested, as we discussed above; therefore, this study did not repeatedly examine these direct relationships.

2.2OBSE as a moderator of the abusive supervision-work outcome relationshipsHigh-OBSE employees tend to rate themselves high on organizational competence, worthiness, and importance. Mistreatment by a supervisor suggests that the abused employee is not valued (Brockner, 1988; Vogel & Mitchell, 2017). Accordingly, abused high-OBSE employees are likely to perceive threatened egotism. The reason is that abusive supervision, such as withholding important information and humiliating or ridiculing subordinates (Zellars et al., 2002), would undermine abused subordinates’ sense of self-worth and importance in the organization. When their favorable views of themselves in the organization are challenged, high-OBSE employees would feel insulted, which then would lead to a perception of threatened egotism. Employees with a threatened egotism would likely become most defensive and aggressive (Baumeister et al., 1993; Baumeister et al., 1996; Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Kinrade et al., 2022; Lata & Chaudhary, 2022) because, based on a self-enhancement motive (e.g., Taylor & Brown, 1988), people are unwilling to downgrade their self-evaluations (Baumeister et al., 1996). In addition, the self-enhancement motive suggests that people desire to develop the most favorable self-appraisals, and therefore, they search for any opportunity to do so.

Baumeister et al. (1996) noted that when individuals with favorable views of themselves receive unfavorable feedback, they are likely to lash out against the source of the feedback because of the self-enhancement motive. Accordingly, in the organizational context, abused high-OBSE subordinates tend to respond fiercely to the threat of their egotism. Based on the negative norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), they would retaliate against their supervisor and organization by engaging in more workplace deviance, lowering their affective organizational commitment, and increasing their intentions to quit. The reason is that threatened egotism makes high-OBSE employees retaliate against the supervisor and the organization to vent their anger and defend their sense of self (Vogel & Mitchell, 2017).

In contrast to abused high-OBSE employees, abused low-OBSE employees are less likely to perceive threatened egotism because they tend to perceive themselves as less valuable and competent. Therefore, they are more likely to accept their supervisor's negative feedback because of the minor discrepancy between their view of self, employees’ unfavorable evaluation, and the negative feedback received due to an abusive supervisor's mistreatment. Baumeister et al. (1996) suggested that individuals with less favorable self-evaluations recognize fewer external appraisals as unacceptable. The strongest negative responses to external appraisal will arise when high self-esteem individuals receive a negative appraisal (Baumeister, 1997). Consequently, low-OBSE employees should be less likely to perceive threatened egotism and then less likely to retaliate against the abusive supervisor and the organization. Therefore, based on the theoretical framework of the theory of threatened egotism discussed above, this study presented the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. OBSE moderates the negative relationship between abusive supervision and affective organizational commitment, and this negative relationship is stronger for individuals with higher rather than lower OBSE.

Hypothesis 2. OBSE moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and intentions to quit, and this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with higher rather than lower OBSE.

Hypothesis 3. OBSE moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance, and this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with higher rather than lower OBSE.

Hypothesis 4. OBSE moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and organizational deviance, and this positive relationship is stronger for individuals with higher rather than lower OBSE.

3Method3.1Data sourcesThe author used convenience sampling and, through interpersonal relationships, invited 55 companies, of which 61.8 % were service and 38.2 % were manufacturing companies, to participate in this study. All companies were located in Taiwan. This study collected the data at two time-points to reduce common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The participant's gender, age, organizational tenure, education, position, abusive supervision, and OBSE were collected at Time 1. A month later, at Time 2, participants’ affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance were collected. Time 1 and Time 2 questionnaires were coded to facilitate matching.

After the senior managers of these companies approved the participation in the survey, trained research assistants distributed and gathered the Chinese version of the questionnaires in sealed envelopes. Subsequently, with the assistance of each company's personnel secretaries, research assistants identified and verbally invited participants who were eligible for this study. The number of participants invited from each of the 55 companies ranged from three to 39, based on the number of employees within the company. At Time 1, research assistants distributed 300 questionnaires to the participants with the help of each company's personnel secretaries. All 300 responses were returned to the author by the research assistants. At Time 2, 300 questionnaires were distributed to the participants. At each time, a cover letter explained the voluntary nature of participation and guaranteed the participants’ anonymity. The participants were verbally instructed to complete the questionnaires at the workplace within seven days and return the finished questionnaires to their company's corresponding secretary in sealed envelopes. The response rate at Time 1 was 100 %, probably because each participant was invited individually, kindly reminded by email to finish the survey within seven days, and rewarded with a ballpoint pen each time. At Time 2, 288 responses were gathered and returned to the author. After excluding incomplete responses, 284 complete responses constituted the sample.

Of the 284 respondents, 58.1 % were female, and 51.7 % had at least a college education. Regarding the respondents’ position in the organization, 73.2 % were operatives, 19.7 % were first-line managers, 5.3 % were middle managers, and 1.8 % were top managers. Respondents had an average tenure of 68.25 months (s.d. = 80.40) and an average age of 34.54 years (s.d. = 13.78).

3.2MeasuresBecause all the measures were originally constructed in English, the translation was conducted and carefully rechecked by the author to ensure the equivalence of Chinese and English measures (Brislin, 1986). Unless otherwise noted, all response options ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 5, “strongly agree.” For each measure, item scores were averaged to form the overall score of the measure.

Abusive supervision. This variable was measured with Tepper's (2000) 15-item scale. The participants rated items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “very often” to indicate how often their supervisor performed each of the 15 behaviors. A sample item is “Tells me my thoughts or feelings are stupid.” This scale's reliability was 0.92.

OBSE. We used six items from the scale developed by Pierce et al. (1989) to measure this variable. This six-item scale had good discriminant validity and reliability of 0.90 in Liao's (2015) study. In addition, as Liao's (2015) study and this current study were all conducted in the Taiwanese context, this six-item scale should adequately measure participants’ OBSE in the current study. The items were “I count around here,” “I am important around here,” “I am trusted around here,” “There is faith in me around here,” “I can make a difference around here,” and “I am valuable around here.” This scale's reliability was 0.93.

Affective organizational commitment. We used four items with the highest factor loadings in Allen and Meyer's (1990) study to measure this variable. This four-item scale was used in Flynn and Schaumberg's (2012) study. A sample item is, “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me.” The scale's reliability was 0.92.

Intentions to quit. This variable was measured with two items from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Cammann et al., 1979). These two items were used by Becker (1992). A sample item is, “It is likely that I will actively look for a new job in the next year.” The scale's reliability was 0.90.

Supervisor-directed deviance. This variable was measured using Tepper et al.’s (2009) three-item scale. The participants rated items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “6 or more times” to indicate how often they engaged in each behavior during the previous month. A sample item is “disobeyed my supervisor's instructions.” The scale's reliability was 0.82.

Organizational deviance. This variable was measured with Tepper et al.’s (2009) 11-item scale with the same response options as supervisor-directed deviance. A sample item is “intentionally worked slower.” The scale's reliability was 0.87.

Control variables. Prior to testing the hypotheses of this study, we controlled for gender, age, education, position, and tenure because these variables could have confounded the results. For example, employee tenure was found to be associated with affective organizational commitment (Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012). Gender was coded as 0, “male,” and 1, “female.” Education was coded as 1, “primary school,” 2, “middle school,” 3, “high school,” 4, “vocational school,” 5, “university,” and 6, “graduate school.” Position in the organization was coded as 1, “operatives,” 2, “first-line managers,” 3, “middle managers,” and 4, “top managers.” Age was assessed in years and tenure in months.

3.3Data analysisWe constructed parcels for abusive supervision and organizational deviance according to their unidimensionality because of the computational limitation of latent variable structural models. Following Hui et al.’s (2004) method, we created eight new indicators for abusive supervision and six new indicators for organizational deviance. AMOS 6.0 was then used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the distinctiveness of the variables. The fit of the hypothesized model and several nested alternative models was compared.

Because the 284 participants were nested within 55 organizations, these participants were not independent (Anand et al., 2010). The ICC(1) values, representing the ratio of between-organizations variance to total variance, were 0.165, 0.088, 0.004, and 0.086 for affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance, respectively. This means that, for example, organizational effect accounted for 16.5 % of the total variance in affective organizational commitment. Therefore, upon confirming the study variables’ distinctiveness, we used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) to model and control the organization effects accurately (Bliese, 2000) and examine the study hypotheses.

This study centered all level 1 independent variables around the grand mean (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998) and specified fixed effects for all coefficients at level 2 except the intercept (Anand et al., 2010). To compare different models and demonstrate the effect size, we used HLM with full maximum likelihood estimation (Anand et al., 2010) and conducted deviance tests. The results of this study were based on the generalized least squares (GLS) standard errors (Anand et al., 2010). Moreover, to test hypotheses, we used moderated HLM analyses and standardized the variables used in the interaction term to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991).

4ResultsTable 1 shows the CFA results of testing the distinctiveness of study variables. The fit indexes indicated that the hypothesized six-factor model fit the data better than any of the nested alternative models. The results confirmed the distinctiveness of the study variables. As shown in Table 1, the CFA fit indexes (χ2 = 863.26, df = 362; TLI =0.90; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.07) of the hypothesized six-factor model are significantly better than the CFA fit indexes (χ2 =1039.87, df = 367; TLI =0.87; CFI = 0.88; RMSEA = 0.08) of the five-factor model 1, supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance are combined into a single factor, as we can compare model fit indexes and conduct chi-square difference test (χ2[5] = 176.61, p < .01) (Farh et al., 2007). The above example demonstrates the distinctiveness of supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance. Overall, the factor loadings for all items across all constructs were greater than 0.50 except for one item of the organizational deviance construct, which was 0.48. Almost all the constructs had convergent validity (Nunnally, 1978).

Results of confirmatory factor analysis for the measures of variables studieda.

| Model | χ2 | df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor model | 863.26 | 362 | .90 | .91 | .07 |

| Five-factor model 1: Supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance combined | 1039.87 | 367 | .87 | .88 | .08 |

| Five-factor model 2: Abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance combined | 1282.41 | 367 | .82 | .84 | .09 |

| Five-factor model 3: Organization-based self-esteem and affective organizational commitment combined | 1657.65 | 367 | .75 | .78 | .11 |

| One-factor model | 4287.56 | 377 | .27 | .32 | .19 |

Note. a TLI is the Tucker-Lewis index; CFI, the comparative fit index; and RMSEA, the root-mean-square error of approximation.

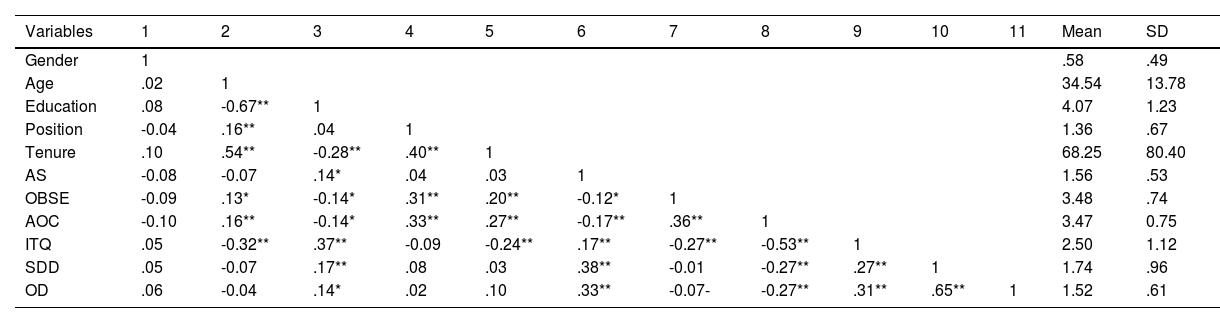

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables are shown in Table 2, and the results of the moderated HLM analyses are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variablesa.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | .58 | .49 | ||||||||||

| Age | .02 | 1 | 34.54 | 13.78 | |||||||||

| Education | .08 | -0.67** | 1 | 4.07 | 1.23 | ||||||||

| Position | -0.04 | .16** | .04 | 1 | 1.36 | .67 | |||||||

| Tenure | .10 | .54** | -0.28** | .40** | 1 | 68.25 | 80.40 | ||||||

| AS | -0.08 | -0.07 | .14* | .04 | .03 | 1 | 1.56 | .53 | |||||

| OBSE | -0.09 | .13* | -0.14* | .31** | .20** | -0.12* | 1 | 3.48 | .74 | ||||

| AOC | -0.10 | .16** | -0.14* | .33** | .27** | -0.17** | .36** | 1 | 3.47 | 0.75 | |||

| ITQ | .05 | -0.32** | .37** | -0.09 | -0.24** | .17** | -0.27** | -0.53** | 1 | 2.50 | 1.12 | ||

| SDD | .05 | -0.07 | .17** | .08 | .03 | .38** | -0.01 | -0.27** | .27** | 1 | 1.74 | .96 | |

| OD | .06 | -0.04 | .14* | .02 | .10 | .33** | -0.07- | -0.27** | .31** | .65** | 1 | 1.52 | .61 |

Note. a n = 284 with listwise deletion; AS: Abusive supervision; OBSE: Organization-based self-esteem; AOC: Affective organizational commitment; ITQ: Intentions to quit; SDD: Supervisor-directed deviance; OD: Organizational deviance; * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Results of HLM analysis for moderation by OBSEa.

| Variables | Outcome:Affective organizational commitment | Outcome:Intentions to quit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 3.46** | 3.47** | 3.47** | 2.50** | 2.50** | 2.50** |

| Gender (γ10) | -0.18* | -0.16 | -0.16 | .07 | .06 | .06 |

| Age (γ20) | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 |

| Education (γ30) | -0.09 | -0.06 | -0.06 | .29** | .24** | .25** |

| Position (γ40) | .27** | .23** | .24** | -0.07 | .02 | .02 |

| Tenure (γ50) | .00 | .00 | .00 | -0.00 | -0.00 | -0.00 |

| Abusive supervision (γ60) | -0.12** | -0.12** | .12* | .12* | ||

| OBSE (γ70) | .15** | .16** | -0.22** | -0.22** | ||

| Abusive supervision × OBSE (γ80) | -0.07* | .09φ | ||||

| Deviance | 587.88 | 565.52 | 561.25 | 816.42 | 799.39 | 796.30 |

| Decrease in deviance | 35.12**b | 22.36**c | 4.27*c | 43.30**b | 17.03**c | 3.09φc |

Note. a n (individuals) = 284; n (organizations) = 55; b Decrease in deviance in comparison to the null model; c Decrease in deviance in comparison to the preceding model; φp < .10;* p < .05;** p < .01

Results of HLM analysis for moderation by OBSEa.

| Variables | Outcome:Supervisor-directed deviance | Outcome:Organizational deviance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 1.74** | 1.74** | 1.74** | 1.53** | 1.52** | 1.52** |

| Gender (γ10) | .06 | .13 | .13 | .03 | .07 | .06 |

| Age (γ20) | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | -0.00 | -0.00 |

| Education (γ30) | .15* | .11 | .12* | .08* | .06 | .07 |

| Position (γ40) | .08 | .06 | .06 | -0.01 | -0.04 | -0.04 |

| Tenure (γ50) | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00* | .00* |

| Abusive supervision (γ60) | .35** | .35** | .19** | .19** | ||

| OBSE (γ70) | .03 | .03 | -0.01 | -0.02 | ||

| Abusive supervision × OBSE (γ80) | .12** | .09** | ||||

| Deviance | 770.61 | 730.61 | 722.99 | 509.49 | 479.14 | 470.03 |

| Decrease in deviance | 11.59*b | 40.00**c | 7.62**c | 7.01b | 30.35**c | 9.11**c |

Note. a n (individuals) = 284; n (organizations) = 55; b Decrease in deviance in comparison to the null model; c Decrease in deviance in comparison to the preceding model; * p < .05;** p < .01

The results of the moderated HLM analysis of Models 1, 2, and 3 examining the moderating effect of OBSE on the abusive supervision-affective organizational commitment relationship are presented in Table 3. In Model 1, only the control variables of gender, age, education, position, and tenure were entered into the HLM model. In Model 2, we examined the direct effects of abusive supervision and OBSE on affective organizational commitment while controlling for control variables. In Model 3, OBSE significantly moderated the relationship between abusive supervision and affective organizational commitment when controlling for control variables, abusive supervision, and OBSE (γ80 = -0.07, p < .05; χ2[1] = 4.27, p < .05). The same approach, depicted in Model 6 of Table 3, revealed that OBSE significantly moderated the relationship between abusive supervision and intentions to quit (γ80 = 0.09, p < .10; χ2[1] = 3.09, p < .10). McClelland and Judd (1993) indicated that compared to optimal experimental tests, it is difficult for field studies to detect moderating effects; therefore, we followed the studies of Seibert and Kraimer (2001) and Özduran and Tanova (2017) in which the moderating effect was significant at p < .10. Moreover, in Model 3 of Table 4, OBSE significantly moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance (γ80 = 0.12, p < .01; χ2[1] = 7.62, p < .01). In Model 6 of Table 4, OBSE significantly moderated the relationship between abusive supervision and organizational deviance (γ80 = 0.09, p < .01; χ2[1] = 9.11, p < .01).

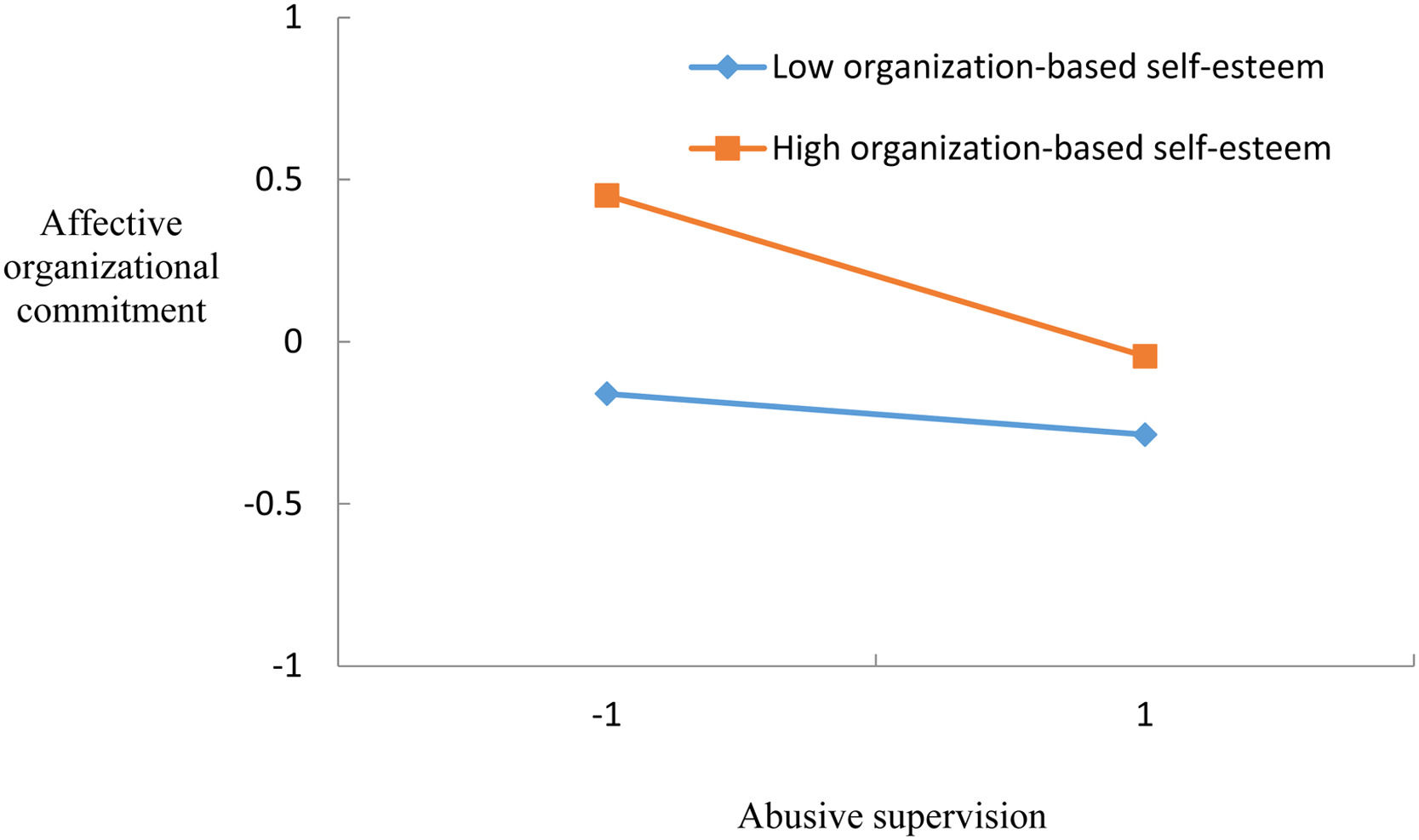

To illustrate the moderating effects of OBSE, Preacher et al.’s (2006) approach was used to calculate the HLM equations for the relationships between abusive supervision and each of the outcome variables at low and high OBSE. This study defined the low and high values as minus and plus one standard deviation from the mean (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). In Fig. 1, the plot of the moderating effect indicates abusive supervision was not significantly associated with affective organizational commitment in low-OBSE employees (simple slope = -0.05, t(221) = -0.92, p = .36); however, abusive supervision was significantly associated with affective organizational commitment in high-OBSE employees (simple slope = -0.19, t(221) = -3.55, p < .01). In Fig. 2, the plot indicates abusive supervision was not significantly associated with intentions to quit in low-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.03, t(221) = 0.41, p = .68); however, abusive supervision was significantly associated with intentions to quit in high-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.21, t(221) = 2.67, p < .01). In Fig. 3, the plot indicates abusive supervision was significantly associated with supervisor-directed deviance in low-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.23, t(221) = 3.32, p < .01) and abusive supervision was significantly associated with supervisor-directed deviance in high-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.48, t(221) = 6.85, p < .01). In Fig. 4, the plot indicates abusive supervision was significantly associated with organizational deviance in low-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.11, t(221) = 2.41, p < .05) and abusive supervision was also significantly associated with organizational deviance in high-OBSE employees (simple slope = 0.28, t(221) = 6.29, p < .01). Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 were fully supported.

Previous literature has indicated that self-esteem could mediate the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes (e.g., Bani-Melhem et al., 2021; Vogel & Mitchell, 2017). For example, Vogel and Mitchell (2017) found that global self-esteem mediates the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes of self-presentational behavior and workplace deviance. A few studies have examined the moderating effect of global self-esteem on the abusive supervision-work outcome relationship (e.g., Burton et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). However, Pierce et al. (1989) suggested that compared to global self-esteem, OBSE should predict organization-associated phenomena more accurately. To date, only Ahmad and Begum (2023) used OBSE rather than global self-esteem to examine self-esteem's moderating effect on the abusive supervision-work outcome relationship. As Ahmad and Begum (2023) tested OBSE's moderating effect on the relationship between abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion, accordingly, our study was the first study to examine the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships of abusive supervision with affective organizational commitment, intentions to quit, supervisor-directed deviance, and organizational deviance. Consistent with the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996), the results of this study indicated that OBSE moderates the relationships between abusive supervision and the work outcomes examined in this work, and these relationships are stronger for employees with higher rather than lower OBSE.

This study included a heterogeneous sample comprising participants from 55 organizations and examined four outcome variables within one study, which may have enhanced the generalizability and credibility of the study results (Lin et al., 2013). To further enhance the credibility of this study, HLM was used to accurately control organization effects on the dependent variables when testing the hypotheses.

This study was the first to explore the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and employees’ retaliation responses toward their supervisor and employing organization, such as supervisor-directed deviance and intention to quit, filling the theoretical gap in previous literature. To explore these moderating effects, this study refined the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) and applied this theory in the organizational context, advancing the previous literature and confirming that the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) is an effective theoretical framework that can be used to interpret the above-stated relationships. To further enhance the knowledge of OBSE's moderating effects on the relationships between abusive supervision and employees’ retaliation responses, future research could further test the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships of abusive supervision with other employees’ retaliation responses, such as reducing supervisor-directed citizenship behavior and organization-directed citizenship behavior.

5.1Theoretical implicationsOur findings contribute to the literature on abusive supervision, OBSE, and threatened egotism in two ways. First, threatened egotism theory (Baumeister et al., 1996) suggests that aggression is most likely to occur when people confront threatened egotism, that is, when people with favorable self-evaluations receive external negative feedback. In the organizational context, this study offers supporting evidence for the theory of threatened egotism. The reason is that high-OBSE employees should be more likely to perceive abusive supervision as threatened egotism than their low-OBSE counterparts. As theoretically predicted, our findings indicated that high-OBSE employees are more likely to seek retaliation toward the source of mistreatment, abusive supervisor, and responsible organization.

Second, our findings suggest that the theory of threatened egotism (Baumeister et al., 1996) rather than the theory of behavioral plasticity (Brockner, 1983) explained better the moderating effects of OBSE on the abusive supervision-work outcome relationships in this study. However, Pierce et al.’s (1993) study indicated that behavioral plasticity theory (Brockner, 1983) could be used to interpret the moderating effects of OBSE on the role condition-employee response relationships, such as the role ambiguity-achievement satisfaction relationship. One reason that could explain their finding is that abused high-OBSE employees are more likely to perceive threatened egotism, whereas low-OBSE employees are more reactive to unfavorable role conditions (Baumeister et al., 1996; Pierce et al., 1993).

5.2Managerial implicationsBased on the results of this study, three managerial implications need to be addressed. First, Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicated that for low-OBSE employees, although abusive supervision was not significantly associated with affective organizational commitment and intentions to quit, it was significantly associated with supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance. However, for high-OBSE employees, abusive supervision was significantly associated with all the work outcomes studied in this research. Therefore, organizations should seek ways to reduce abusive supervision. For example, because a hostile work climate could promote abusive supervision, organizations should develop norms, such as increased interpersonal respect, communication, cooperation, and assistance, to eliminate abusive supervision (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). In addition, organizations should begin training their supervisors to appropriately manage and interact with subordinates (Lin et al., 2013) and treat them with dignity and fairness (Ferris et al., 2012). Moreover, Smith et al. (2022) suggested that organizational leaders should monitor abusive supervision by training supervisors and employees about the negative consequences caused by abusive supervision and encouraging abused employees to speak up.

Second, the results of this study indicated that the relationships between abusive supervision and all the work outcomes in this study were stronger for employees with higher OBSE. In particular, according to Figs. 3 and 4, high-OBSE employees were more likely than low-OBSE employees to engage in more supervisor-directed and organizational deviances when abusive supervision was high. Therefore, to reduce employees’ perceptions of threatened egotism, especially those with high OBSE, and attenuate abused employees’ retaliations against the corresponding supervisor and organization, organizations should seek ways to fortify and restore employees’ OBSE to deal with abusive supervision. For example, enhancing employees’ social inclusion could strengthen their OBSE (Leary, 1990); hence, organizations should provide employees with opportunities to socially connect with other colleagues in the employing organization (Vogel & Mitchell, 2017). Based on Pierce and Gardner's (2004) review of the OBSE literature, Farh and Chen (2014) suggested that organizations must seek interventions to restore abused employees’ OBSE, such as designing jobs that would maximize autonomy and ensure high levels of organizational justice. Furthermore, Świtaj et al. (2015) suggested that organizations could offer abused employees a “self-esteem module” intervention developed by Lecomte et al. (1999) to restore their OBSE following abusive supervision.

Third, previous literature has indicated that OBSE is positively associated with favorable work outcomes, as we mentioned earlier in the introduction section. For example, OBSE has been found to be positively associated with employees’ innovative behavior (Liao et al., 2023). Employees’ innovative behavior was revealed to be positively associated with organizations’ innovation performance (Chen et al., 2018), which is essential for the performance of organizations (Wang & Dass, 2017). Accordingly, in today's knowledge-based economy, to enhance organizations’ performance, organizations ought to offer interventions to increase employees’ OBSE, e.g., empowering leadership (Kwan et al., 2022). However, according to the results of this study, abused high-OBSE employees will respond more fiercely compared to their abused low-OBSE counterparts by engaging in more supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance to retaliate against the abusive supervisor and the employing organization. Therefore, to enhance employees’ favorable work outcomes, such as innovative behavior, organizations should increase the levels of employees’ OBSE and simultaneously prevent abused employees from retaliating against abusive supervisors and organizations to enhance employees’ OBSE and reduce abusive supervision. In addition, supervisors should treat their employees with respect and dignity instead of engaging in abusive supervision to prevent employees’ perceptions of threatened egotism, which would encourage employees to retaliate against their abusive supervisor and employing organization.

5.3Limitations and suggestions for future researchFuture research should consider the following limitations of this study. Although this study used a single source of data, which may inflate the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes, we collected the data at two time-points, one month apart, to reduce the potential of single-source bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition, this study focused on the moderating effects of OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes, not the effects of abusive supervision on work outcomes. As moderating effects involve complex theoretical reasoning, single-source bias should affect these effects less compared to simple linear relationships (Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000). As a result, single-source bias should not have substantially affected the findings of this study. However, in future research, employees’ co-workers could rate some of the work outcomes, such as supervisor-directed deviance and organizational deviance.

Narcissism has been distinguished from self-esteem, and narcissism is moderately and positively associated with self-esteem (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004; Judge et al., 2006). Campbell et al. (2002) argued that “narcissism does not appear simply to reflect exceptionally high self-esteem” (p. 365). Moreover, Fox et al. (2023) indicated that narcissists prioritize their selves over others. Therefore, in an organizational context, future research should include both narcissism and OBSE in the model and compare the moderating effects of narcissism and OBSE on the relationships between abusive supervision and work outcomes.

Data availability statementThe data file for this study is located at https://figshare.com/s/deccfbbd85c89a75e56a.

Ethical statementAll participants were guaranteed anonymity and voluntary participation.

Informed consent statementThis research's participants were notified of the purposes and procedures of this research and ensured that this research's data would be used only for academic purposes.

CRediT authorship contribution statementPen-Yuan Liao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.