A 24-year-old woman presented with a history of chronic watery diarrhea associated to abdominal pain and weight loss. Her father had died of cirrhosis at the age of 47 and her grandmother had died from colorectal cancer at the age of 69.

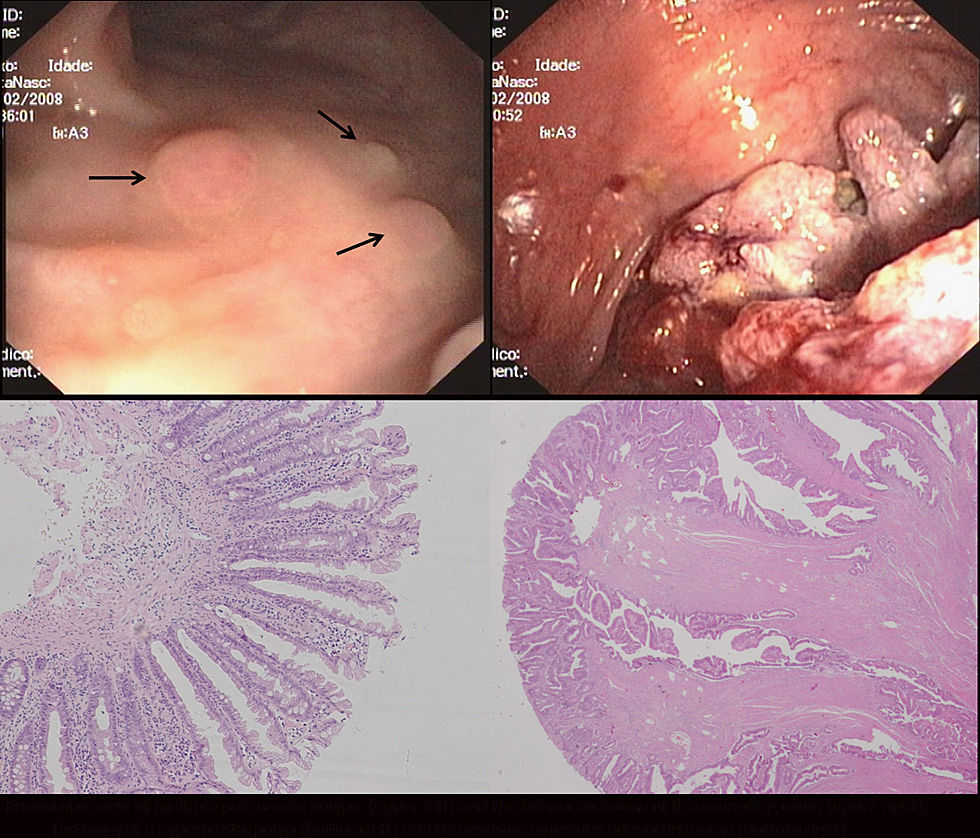

A colonoscopy revealed multiple sessile polyps scattered throughout the colon (ranging from 3 to 15mm), and a large, villous looking lesion located in the ascending colon (Fig. 1). The lesion was biopsied and several polypectomies were performed. The histology was compatible with an adenoma with high grade dysplasia and hyperplastic polyps, respectively.

Total colectomy with ileo-rectal anastomosis was performed. The specimen analysis revealed a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon and the existence of 70 hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas in the remaining mucosa, none of which presented high grade dysplasia or carcinoma. Molecular analysis of the adenocarcinoma revealed a microsatellite stable tumor, BRAF mutation and CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP high). No KRAS mutation was identified.

Genetic analysis was negative for germline mutations in APC and MYH genes.

DiscussionThis young female patient has a colorectal cancer (CRC) in the setting of a hyperplastic polyposis syndrome (HPPS). HPPS is a rare preneoplastic condition characterized by the existence of multiple hyperplastic polyps in the colorectal mucosa. CRC risk is actually unknown, but can be over 50%.1 CRC risk can be increased in patients with numerous, large or dysplastic polyps. This case fulfills the WHO criteria for HPPS diagnosis, since there were more than thirty hyperplastic polyps dispersed throughout the colon.

It has been proposed that HPPS could represent a paradigm for the “serrated pathway” of colorectal carcinogenesis, in which progression would occur through the Hyperplastic polyp (HP)>Serrated adenoma (SA)>CRC sequence. This pathway is thought to be expressed in sporadic CRC arising mainly from the right colon, with BRAF mutation, methylator phenotype and microsatellite instability (MSI). Although the “serrated pathway” is obviously important in HPPS patients, there seems to be a great heterogeneity in the pathology and molecular characteristics of the colorectal neoplasia in these patients. In fact, Carvajal-Carmona et al could not demonstrate a higher prevalence of MSI in colorectal neoplasia of 32 patients with HPPS, even if they had a higher frequency of BRAF or KRAS mutations.2 These authors demonstrated that polyps of HPPS patients have either BRAF or KRAS mutations, but not both. Also demonstrating the variety of clinical–pathological pictures in HPPS is the recent report of HP and SA in patients with MYH-associated polyposis.3 The fact that there is no known genetic basis for this syndrome increases the difficulty in explaining such a wide variety. It is possible that this syndrome represents a unique entity that increases the susceptibility to several subtypes of colorectal neoplasia or that there are in fact several diseases enclosed in the HPPS phenotype.

Management strategies for patients with HPPS and their families are not well-defined. Current guidelines acknowledge the increased CRC risk of this condition and suggest increased endoscopic surveillance.4

We offered the patient annual endoscopic surveillance of the rectal stump with narrow banding imaging.5 Screening colonoscopy with NBI was also offered to the patient's first degree relatives and no colorectal polyps were found.