Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a type of acute-on-chronic liver failure and is the most severe form of alcoholic liver disease. AH occurs in patients with heavy alcohol abuse and underlying liver disease. In its severe form, AH carries a poor short-term prognosis. Although the existence of AH can be strongly suspected based on clinical and biochemical criteria, a definitive diagnosis requires a liver biopsy. There is a clear need to develop non-invasive markers for these patients. The prognosis of patients with AH can be established by different score systems (Maddrey's DF, ABIC, MELD and Glasgow). Recently, a histological scoring system able to estimate prognosis has been developed (Alcoholic Hepatitis Histological Score – AHHS). The management of patients with AH has changed little in the last few decades. In patients with severe form of AH, prednisolone and pentoxifylline are the first line therapy. Unfortunately, many patients do not respond and novel targeted therapies are urgently needed. Current research is aimed at identifying the main disease drivers and to develop animal models of true AH. For non-responders to medical therapy, the only curative option is to perform a salvage liver transplantation. This particular indication of liver transplantation is currently under debate and prospective studies should evaluate the specific patient evaluation and selection criteria.

La hepatitis alcohólica (HA) es un tipo de fallo hepático agudo sobre crónico y es la manifestación más severa de la hepatopatía alcohólica. La HA ocurre en pacientes con ingesta muy elevada de alcohol y con hepatopatía de base. En sus formas severas, la HA conlleva un pésimo pronóstico. La existencia de una HA puede ser sospechada combinando criterios clínicos y analíticos. Sin embargo, el diagnóstico definitivo de una HA requiere una biopsia hepática. El pronóstico de los pacientes con HA puede realizarse mediante diferentes escalas (Maddrey's DF, ABIC, MELD y Glasgow). Recientemente, se ha descrito una escala histológica capaz de estimar el pronóstico de estos pacientes (Alcoholic Hepatitis Histological Score -AHHS-). El manejo de los pacientes con HA no ha cambiado en exceso en las últimas décadas. Para los pacientes con formas severas, los tratamientos de primera línea son la prednisolona y la pentoxifilina. Desgraciadamente, muchos pacientes no responden y nuevas terapias moleculares son necesarias. En la actualidad, la investigación se centra en la identificación de los responsables moleculares de esta enfermedad y en el desarrollo de modelos animales de HA. Para los pacientes que no responden a la terapia médica, la única opción curativa es realizar un trasplante hepático. Esta indicación de trasplante está en debate en la actualidad y estudios prospectivos deberían determinar los criterios de evaluación y de selección de estos pacientes.

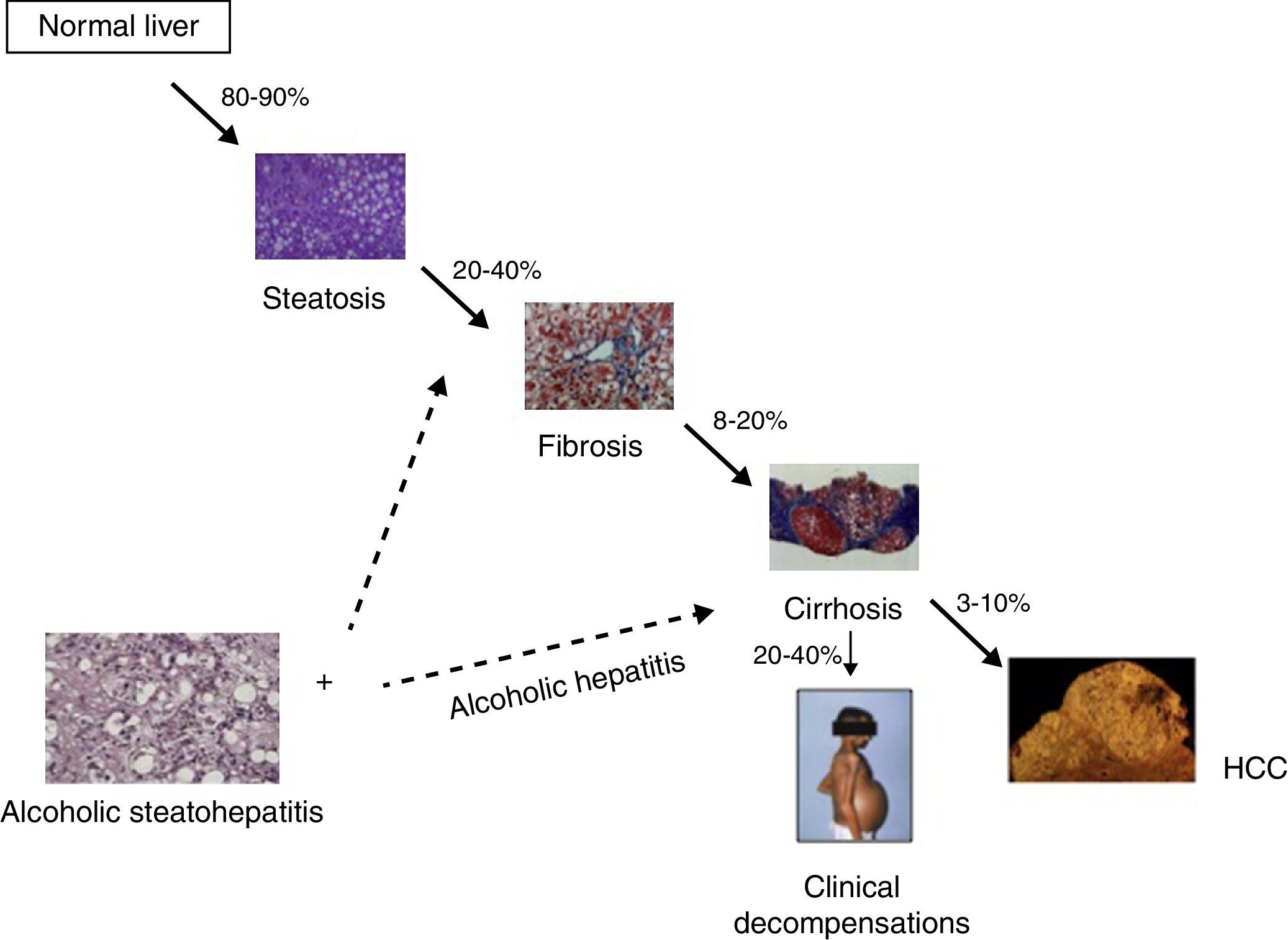

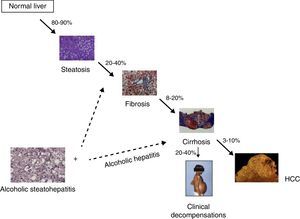

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the commonest causes of advanced liver disease worldwide. The disease spectrum ranges from fatty liver to steatohepatitis, progressive fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma1 (Fig. 1). ALD is one of the leading factors of liver fibrosis in the general population as well as cirrhosis.2 Compared to the recent advances in viral hepatitis, few advances have been made in its prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of ALD. The lack of advances in the field of ALD are due to intrinsic difficulties in performing clinical trials in patients with an active addiction, a poor knowledge of molecular drivers in humans and the lack of experimental model of advanced ALD.

The spectrum of alcoholic liver disease. The percentages represent the patients who progress from one stage to the next. Steatohepatitis can occur in patient at earlier stages, and probably influences disease progression. When steatohepatitis occurs in patients at advanced stages, a clinical syndrome called “alcoholic hepatitis” frequently develops.

Patients with chronic alcohol misuse can present with histological criteria of steatohepatitis (ASH) at different stages of the disease.3 This early form is poorly characterized in humans and there is a clear need to delineate its natural history and prognostic factors as well as to develop reliable non-invasive markers. Early detection of initial forms of ALD in the primary care setting and subsequent behavioral interventions should be encouraged. Although the lesions defining ASH do not differ from those described in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), ASH is usually associated with more severe histological lesions and a worse clinical course. In addition, patients with advanced ALD (in most cases cirrhosis) and active drinking can develop an episode of acute-on-chronic liver failure named “alcoholic hepatitis” (AH).1 In most alcoholic patients with this clinical syndrome, the histological analysis shows the presence of ASH and advanced fibrosis. In its severe forms, AH carries a bad prognosis and current therapies are not fully effective. This article summarizes the clinical, analytical and histological features of AH and discusses the therapeutic options for these patients.

Clinical presentationAH should be considered as a clinical syndrome defined by the recent onset of jaundice and/or liver decompensation (i.e. ascites) in a patient with chronic alcohol abuse. In the past, AH was referred to as “acute alcoholic hepatitis”, however the term “acute” is not entirely accurate. Although the clinical presentation may present abruptly, it is felt to reflect an exacerbation of underlying chronic liver disease. It is important to clarify that while AH is a clinical syndrome, the existence of ASH needs to be confirmed histologically.

The hallmark of symptomatic AH is the abrupt onset and/or rapid progression of jaundice, which may or may not be associated with fever, infection, weight loss, malnutrition, and an enlarged, tender liver. In severe cases, AH may induce liver decompensation with ascites, encephalopathy, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Laboratory evaluation typically demonstrates AST levels that are elevated to 2–6 times the upper limit of normal with an AST/ALT ratio that is greater than 2. Increased bilirubin and neutrophilia are also frequently observed. Serum albumin may be decreased, prothrombin time prolonged and the international normalized ratio (INR) may be elevated; however, these values depend on the severity of the episode. Patients with severe AH are prone to develop bacterial infection and acute renal failure due to type 1 hepatorenal syndrome.4

Although the existence of AH can be highly suspected based on clinical and analytical criteria, a definitive diagnosis requires histological confirmation. Due to the existence of coagulopathy in most patients, a transjugular biopsy is frequently indicated in this setting. In most cases, advanced liver fibrosis (mainly cirrhosis) and superimposed ASH are found. When using a Tru-Cut instead of a fine needle, most patients show signs of cirrhosis. ASH is defined by the coexistence of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning and/or Mallory-Denk bodies, and an inflammatory infiltrate with PMNs. A typical finding in many patients is the presence of megamitochrondria. Importantly, canalicular and/or lobular bilirubinostasis is commonly seen in AH, especially in patients with ongoing bacterial infections. It is important to note than in 20–25% of patients, a true ASH is not found. Other histological findings include signs of drug-induced liver disease, ischemic hepatitis (especially in patients with cocaine consumption), foamy hepatic degeneration and biliary obstruction.

The incidence of AH remains largely unknown. A Danish population-based retrospective cohort study estimated that it ranges from 24 to 46 per million, depending on gender, and is increasing.5 A large study, where systematic liver biopsies were performed in 1604 alcoholic patients, found the prevalence of AH to be approximately 20%.6 In symptomatic patients, including those with decompensated liver disease, the prevalence of AH is not well known, partly because most centers rely on clinical criteria rather than transjugular liver biopsy as routine practice in the diagnosis of patients with decompensated ALD. Relying only clinical criteria alone carries a 10–50% risk of misclassifying patients as having or not having AH.7–9 Therefore, the recently published EASL Practical Guidelines on Alcoholic Liver Disease10 strongly recommends performing a liver biopsy, if available, in patients with suspected AH.

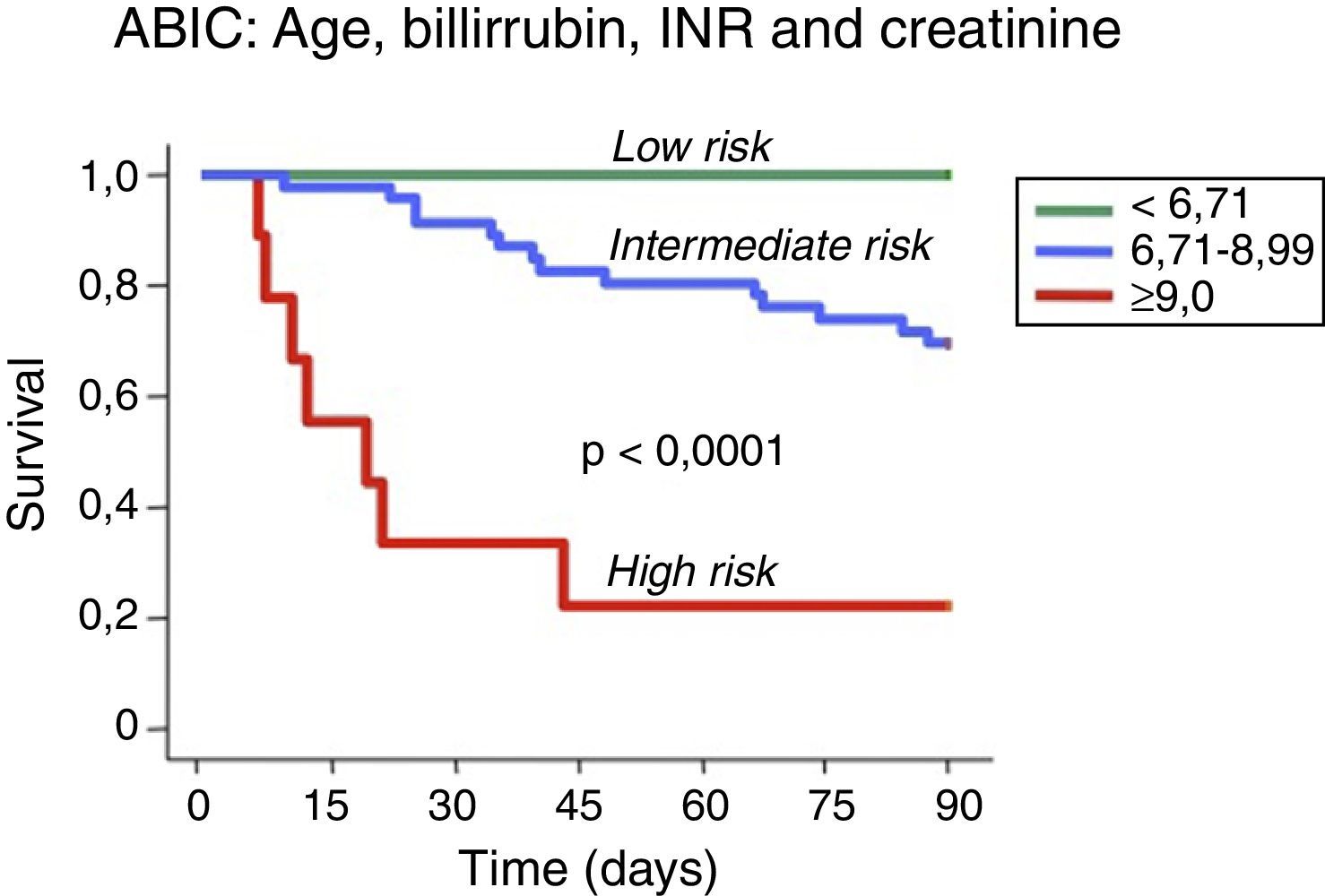

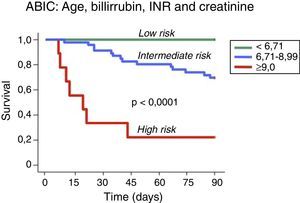

Assessment of prognosisThe prognosis of patients with AH can be estimated using biochemical and histological criteria. Several prognostic models have been developed to identify patients with AH who are at high risk of death within 1–3 months of their hospitalization. Maddrey's discriminant function (DF)11 was the first score to be developed and remains the most widely used. Severe AH is defined as a DF >32 and the reported 1-month survival of untreated patients with a DF >32 ranges from 50% to 65%.12 Other prognostic scores, such the MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease), the GAHS (Glasgow ASHScore) and the ABIC score (age, serum bilirubin, INR, and serum creatinine score) have been proposed for use in the setting of AH13–16 (Fig. 2). Although the initial studies evaluating these scores suggest higher prognostic accuracy in predicting 28-day and 90-day outcomes than the DF, external validation is still necessary for many of them. Furthermore, the proposed cut-offs of these scores need to be tested in populations other than those used initially for score development. Another limitation of some prognostic models developed for AH is that they only stratify patients into two categories, severe or non-severe, and only early mortality risk is considered. A proportion of patients may not meet the criteria for severe AH and may die at time points longer than one month, i.e. up to six months. Their prognosis needs to be better defined. The ABIC score classifies patients according to low, intermediate or high risk of death13 and this classification may permit better evaluation of therapies for AH.

Prognostic stratification of patients with alcoholic hepatitis according to the ABIC (age, bilirubin, INR and creatinine) score.13

The most widely used scoring system to evaluate the response to therapy is the Lille Model.17 The Lille score determines prognosis on the basis of response or nonresponse to prednisolone and incorporates the serum bilirubin at baseline and at day 7. A recent meta-analysis was able to categorize patients as complete responders, partial responders or null responders and was able to predict the 6-month survival of each group using 2 new cut-offs of the Lille score.18 Another factor that predicts mortality in AH is the development of acute kidney injury (AKI), defined as an absolute increase of serum creatinine of 0.3mg/dL, or a 50% increase above baseline. AKI is associated with a marked decrease in 90-day survival. Interestingly, patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) at admission developed AKI in much higher proportions and SIRS was also associated with decreased 90-day survival.19 Neither SIRS nor AKI has been incorporated into a prognostic model at this point.

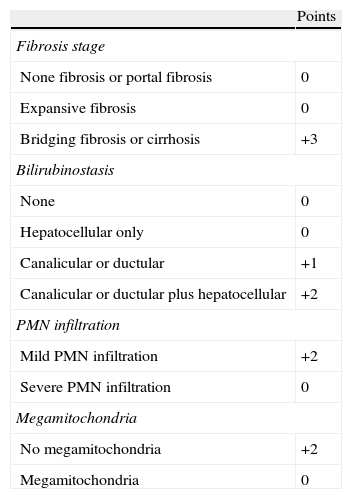

Recently, we performed a large multicentre study to develop a histological scoring system capable of predicting short-term survival in patients with AH. The resulting Alcoholic Hepatitis Histological Score (AHHS) comprises 4 parameters that are independently associated with patients’ survival: fibrosis stage, PMN infiltration, type of bilirubinostasis and presence of megamitochondria (Table 1). By combining these parameters in a semiquantitative manner, we were able to stratify patients into low, intermediate, or high risk for death within 90 days.20

Alcoholic Hepatitis Histological Score (AHHS) for prognostic stratification of alcoholic hepatitis.

| Points | |

| Fibrosis stage | |

| None fibrosis or portal fibrosis | 0 |

| Expansive fibrosis | 0 |

| Bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis | +3 |

| Bilirubinostasis | |

| None | 0 |

| Hepatocellular only | 0 |

| Canalicular or ductular | +1 |

| Canalicular or ductular plus hepatocellular | +2 |

| PMN infiltration | |

| Mild PMN infiltration | +2 |

| Severe PMN infiltration | 0 |

| Megamitochondria | |

| No megamitochondria | +2 |

| Megamitochondria | 0 |

AHHS categories (0–9 points): mild, 0–3; intermediate, 4–5; severe, 6–9.

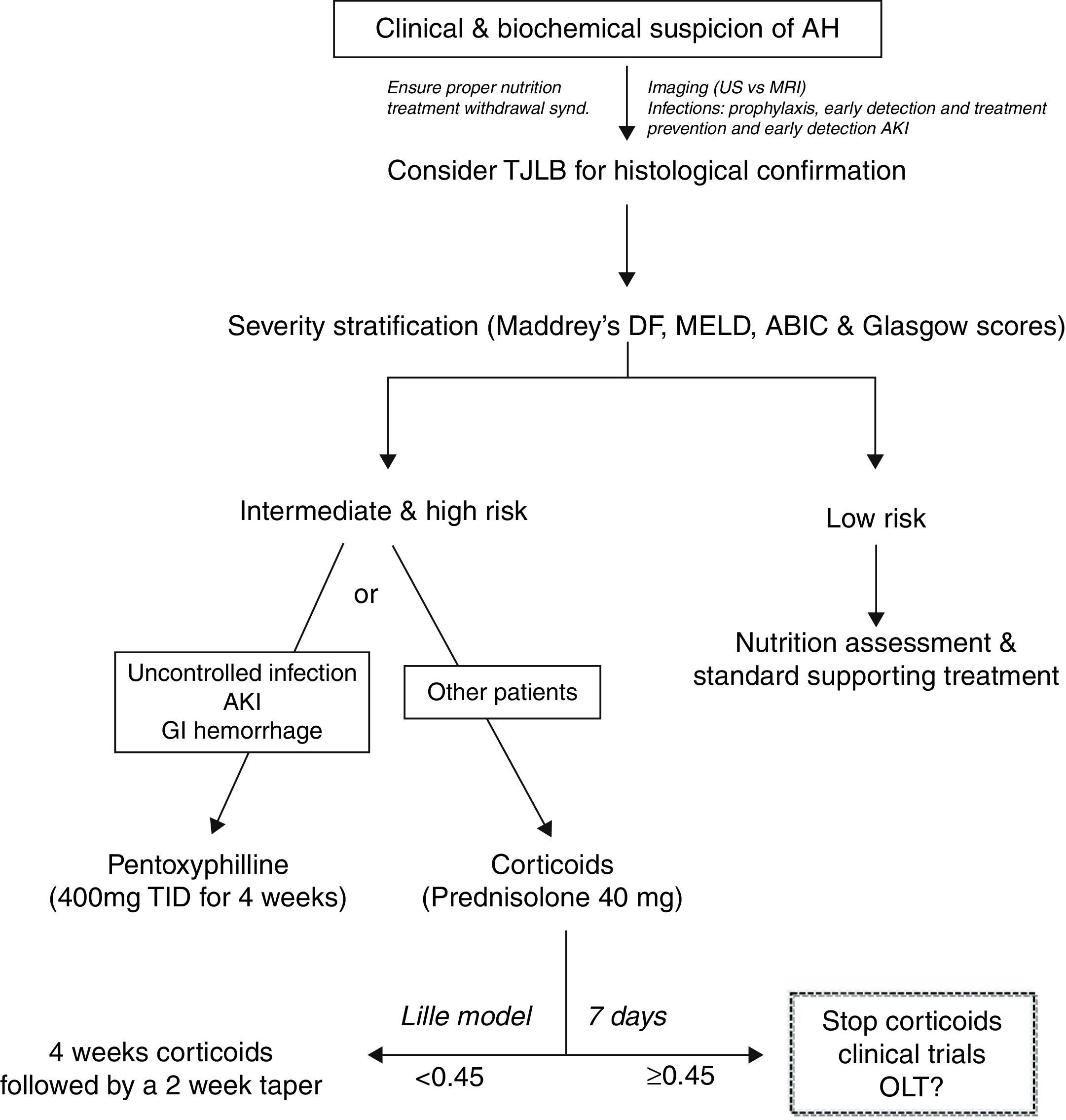

Despites its poor outcome, the treatment of patients with AH has not substantially improved in the last few decades. As an example, the gold-standard therapy for severe cases (i.e. prednisolone) was proposed more than 40 years ago.21 The development of novel therapies is limited by poor knowledge of the main molecular drivers, the lack of animal models of AH and the limited research attention that this field receives among academic hepatologists. There is a clear need to develop novel targeted therapies for patients not responding to existing drugs. Fig. 3 shows an algorithm for the therapy of patients with AH.

In patients with severe AH, patients may need admission to an intensive care unit, especially if there are concerns about ability to protect the airway in the acutely intoxicated or in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Benzodiazepines are generally contraindicated in these patients, but might be necessary in the case of severe alcohol withdrawal. There is a potential risk of Wernicke's encephalopathy among alcoholic and malnourished patients, thus the administration of B-complex vitamins is recommended. Daily protein intake of 1.5g/kg body wt is also advised. Because patients with AH are predisposed to develop severe infections, which may threaten survival, early diagnosis and empiric antibiotic treatment are advised. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is recommended in patients with ascites and elevated bilirubin, while there is no evidence supporting the use of empiric antibiotics in the remaining patients.

PrednisolonePrednisolone is widely considered the first line therapy for severe AH. Both the AASLD and EASL practice guidelines recommend the use of corticosteroids (i.e. prednisolone 40mg daily for 4 weeks) for patients with severe AH, defined by Maddrey's discriminant function >32 or the presence of hepatic encephalopathy.10,22 However, the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of AH is controversial because of disparate findings from individual studies and meta-analyses. Some meta-analyses reported that corticosteroids increased patient survival times,18,23 while others did not support the use of corticosteroids due to the heterogeneity of the clinical trials being analyzed and the high risk of bias.24 The contraindications for the use of corticosteroids are not well defined. In some centers, patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding, sepsis or poor metabolic control are treated with alternative therapies (i.e. pentoxifylline). When treated with corticosteroids, patients must be monitored intensively for evidence of or for development of infections. Infections occur in almost 25% of patients during corticosteroid treatment and are associated with poor prognosis.25 The Lille score can be calculated after 7 days of initiation of therapy and corticosteroids can be stopped in non-responders, defined by a Lille score >0.4520. A Lille score greater than 0.45 predicts a 6-month survival rate of less than 25%.17 A recent study suggests that theophylline administration could increase sensitivity to corticosteroids.26 Drugs that improve the efficacy of corticosteroids in treating AH are an interesting area for further research.

PentoxifyllinePentoxifylline is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that blocks transcription of TNF-α. It can be used to treat patients with severe AH who cannot tolerate corticosteroids. Importantly, pentoxifylline is not effective rescue therapy in patients who tolerate, but do not respond to corticosteroids.27 Pentoxifylline was shown to reduce the mortality of patients with severe AH, which was related to decreased development of hepatorenal syndrome.28,29 However, this mortality benefit was not noted after adjusting for multiple testing.30 Pentoxifylline seems particularly indicated in patients with contraindications for corticosteroids, and in those with high risk of developing AKI. A large clinical trial comparing prednisolone versus pentoxifylline is still lacking and will clarify the precise indications for these agents.

TNF-α blocking agentsThe use of these agents is based on experimental studies showing that TNF-α has an important role in the pathogenesis of ALD, although recent translational studies do not support this hypothesis.31,32 There have been clinical studies assessing the effect of infliximab or etanercept, anti-TNF-α agents, in patients with AH. A small randomized-controlled pilot study showed improvement in DF and survival,33 however later, larger studies showed increased rates of infection and increased mortality.34,35 Therefore, anti-TNF-α agents are not recommended for treatment of AH.

NutritionMalnutrition is a common feature of alcoholic patients and may favor bacterial infections. Nutritional support improves liver function and short-term follow-up studies suggest that improved nutrition might improve survival times and histological findings in patients with AH.36–38 Although the level of evidence is modest, nutritional support is recommended in patients with AH. In patients without encephalopathy, oral supplements and/or feeding through a nasogastric tube is preferred over total parenteral nutrition in order to avoid gram-positive bacterial infections.

S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe)SAMe, a methyl donor, regulates hepatocyte growth, death and differentiation and has been shown to protect against alcoholic livery injury via multiple mechanisms that include antioxidant functions, maintenance of mitochondrial function, and down-regulation of TNF-α.39 A randomized-controlled trial showed that administration of SAMe decreased mortality and the need for liver transplantation among patients with ALD and had a favorable safety profile.40 On the contrary, a Cochrane systematic review found no evidence to support or refute the use of SAMe in patients with ALD.41 Therefore, the usefulness of this drug should be confirmed in large randomized trials.

Liver transplantationTraditionally, patients with severe AH were not considered as candidates for transplantation due to their active alcohol misuse. However, a recent study has assessed the feasibility of performing liver transplantation to highly selected patients with AH that did not respond to corticosteroids. This provocative study showed that the outcomes are equal to or better than those obtained when transplantation is used to treat end-stage liver disease from other conditions.42 Importantly, only less than 2% of patients admitted to the participating centers with an episode of AH were listed for a liver transplant. Although the follow-up was limited, the rate of alcohol relapse was extremely low (3 out of 26 patients). The rationale behind this study is that patients with severe AH who do not respond to medical treatment are unlikely to survive the “mandatory” 6-month abstinence period as their risk of mortality is quite high.43,44 Of course, these patients should fulfill all other criteria for liver transplantation and must have a thorough psychosocial evaluation to determine candidacy. This study has opened a debate among the liver transplantation community that includes medical and ethical considerations. While waiting for external validation, liver centers in many countries are increasingly considering liver transplantation as a rescue therapy for patients who fail to respond to medical therapy.

Other therapiesThere are no additional therapies approved for the treatment of AH. Androgenic steroids have been used in attempts to improve the nutritional status of patients with AH. Initially, trials with oxandrolone had positive results, however these results were not confirmed in further studies and no benefit was shown in a meta-analysis.45 Propylthiouracil is an antithyroid drug that has also been evaluated for the treatment of acute AH, however a meta-analysis of 6 clinical trials showed no benefit of propylthiouracil on survival.46 Furthermore, propylthiouracil has been associated with adverse effects. Because ALD is associated with increased levels of oxidative stress, a number of studies have investigated the benefits of antioxidants such as silymarin47 and vitamin E.48 However, survival times in patients with AH did not increase when treated with these agents. A more promising approach is to treat patients with severe AH with combination therapy comprised of N-acetylcysteine with corticosteroids. N-acetylcysteine is known to replenish glutathione in damaged hepatocytes and prevent cell death in ALD. A recent large study showed a clear trend to improve survival, although the study was underpowered to reach statistical significance.49

Treatment of alcohol misuseCessation of the alcohol misuse is of paramount importance in the management of patient with AH. Behavioral therapy must be a central component of alcoholism treatment. In patients with a first episode of AH, brief motivational interventions are encouraged during the first hospitalization, although this approach is limited by poor mental status in many patients. The four main parameters that should be considered and assessed when approaching these patients are: self-awareness of alcohol misuse, appropriate family/social support, underlying psychiatric disorders and willingness to be seen by an addiction therapist.50 For the successful management of these patients, a multidisciplinary team composed of hepatologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers is highly recommended.

Anticraving drugs can be considered to increase success for abstinence. Disulfiram has been used in the past and works well,51 but there have been case reports of disulfiram-induced severe hepatitis,52 which clearly limit its use in patients with ALD. Naltrexone was found to decrease heavy drinking in alcoholics53 both alone and when combined with a behavioral approach,54 however there is also concern for hepatotoxicity with this agent and it has not been tested in patients with ALD. Other compounds known to prevent alcohol relapse include acamprosate, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid and topiramate.55–57 The usefulness of all these compounds in the setting of ALD have not been adequately assessed. A more promising compound is baclofen, a derivative of GABA that binds to the GABAB receptor. Baclofen is the only agent that has been tested in patients with advanced ALD and demonstrated a significant improvement in the proportion of patients abstinent from alcohol, when compared to placebo, with no hepatic side effects seen.58 Studies assessing the efficacy and safety of anticraving drugs in the setting of AH are warranted.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.