A 78-year-old male presented with a 6-months complain of progressive dysphagia for solids and liquids. He had a previous medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and arterial hypertension and had been previously diagnosed and successfully treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. He also had been submitted to an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy 2 years previously for heartburn, with no abnormalities.

The patient reported no other symptoms, and physical examination was unremarkable.

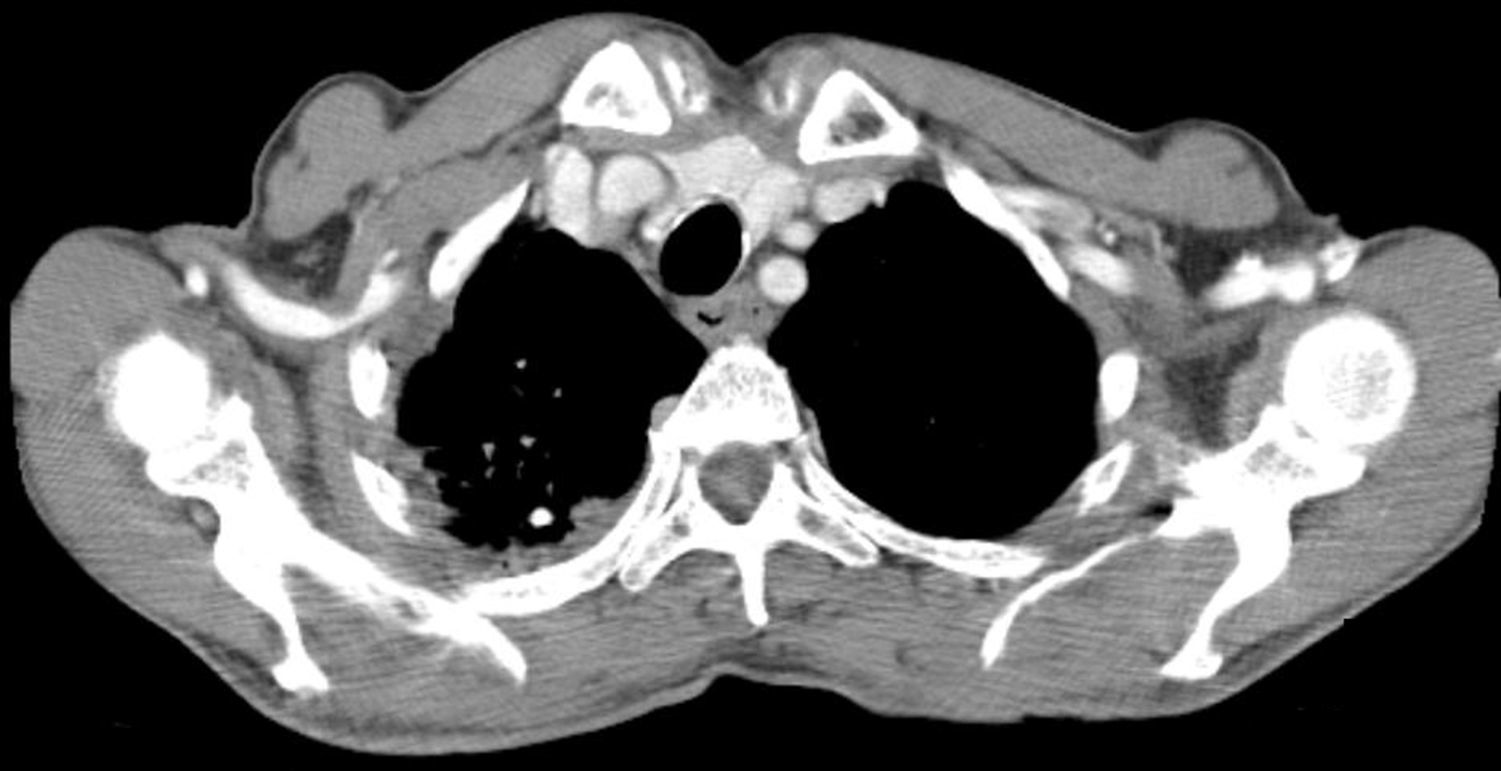

Laboratorial analysis showed normal hemogram values, as well as ionogram, renal and liver function, and normal albumin and total serum proteins. A thorax CT-scan, performed a few days earlier for COPD evaluation, revealed a moderate parietal thickening of the esophagus, more pronounced in its middle third, with subserosal small cystic collections of air (Fig. 1).

We performed an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, revealing numerous, coalescent and easily depressible mucosal protrusions along the entire esophagus, without significant luminal stenosis, compatible with pneumatosis of the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 2). Both the stomach and duodenum were endoscopically normal.

Following the procedure, a conservative management was decided, and the patient remained as outpatient without directed treatment, with significant clinical improvement during the next 6 months.

Pneumatosis of the gastrointestinal tract (PGIT) is an uncommon disease, of unknown origin, characterized by the presence of gas within the intestinal wall.1 Despite the fact that the first case of PGIT was described in 1730, by Du Vernoi, it is still poorly understood and seldom studied. Both genders are equally affected by this disease, most frequently in the forth and fifth decades,2 and although it may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the rectum, it is far more frequent in the colon (46%) and the small bowel (27%).3 Both rectal and gastric PGIT have been described in the literature, but esophageal pneumatosis is exceedingly rare, with scarcely any cases reported so far in the literature.4,5

Only a minority of the PGIT cases has been classified as primary or idiopathic, while 85% present with an underlying pathology.2 Most cases of secondary PGIT are related to gastrointestinal disorders, such as necrotizing enterocolitis, peptic ulcer disease and intestinal obstruction,6 but other diseases, including COPD, asthma, auto-immune diseases, leukemia and organ transplantation have been linked to PGIT as well.4 Finally, surgery, endoscopic procedures and traqueal intubation have been reported as causative factors for PGIT.4

Despite the number of diseases associated with PGIT, the pathogenesis of PGIT is yet only partially understood. Several mechanisms are believed to be involved, and include the mechanical theory, where damage to the bowel wall through inflammation, necrosis, obstruction or trauma results in air dissection through a mucosal tear,7 the bacterial theory, stating that cysts are created by gas-forming bacteria who entered the intestinal wall through increased mucosal permeability,8 and the pulmonary theory, in which pulmonary diseases result in alveolar rupture with consequent air dissection through the mediastinum along the aorta and mesenteric vessels.1 None of these mechanisms alone have been confirmed as the sole cause of PGIT; rather, likely a conjugation of some or all of them is needed for the formation and maintenance of cysts within the digestive wall.1,4

PGIT is often asymptomatic, but may present with a wide variety of symptoms, depending on its location. Small bowel and colonic pneumatosis may present with abdominal pain, diarrhea or haematochezia,1 while esophageal pneumatosis usually presents with dysphagia or retrosternal pain.4

While endoscopic biopsies confirming cyst collapse may still be employed, it is no longer required, and PGIT may easily be diagnosed with the combination of several translucent and depressible cysts observed during endoscopy with the identification of intramural air on CT imaging.9 Management of PGIT depends on its underlying cause, and include parenteral nutrition, hyperbaric oxygen, antibiotic therapy, as well as endoscopic treatment with cystic puncture and sclerotherapy, while surgery is currently restricted to patients in septic shock, intestinal obstruction or perforation.10 Importantly, a vast majority of patients with moderate symptoms will spontaneously improve without treatment over a period of several weeks to months.1

In conclusion, PGIT is a rare and still poorly comprehended phenomenon associated with a wide variety of diseases and nonspecific presentation. Our case highlights an exceptionally rare instance of esophageal pneumatosis in a patient with previously diagnosed COPD, supporting a probable causal link between pulmonary diseases and PCI development.

FundingNo funding or grant was received for this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.