It has been proposed that non-invasive methods may replace liver biopsy for the diagnosis of tissue damage in patients with autoimmune liver disease (ALD). The aim of this study was to determine diagnostic performance and degree of concordance between the APRI index and liver biopsy for diagnosing cirrhosis in these patients.

Material and methodsIn a cohort of patients with ALD, the value of the APRI index and liver biopsy results were determined according to the METAVIR score. The AUC and the degree of concordance between an APRI value >2 and a METAVIR score of F4 were evaluated as markers of liver cirrhosis, through a kappa statistic.

ResultsIn total, 70 patients (age 51 ± 13 years) were included. The most common autoimmune liver diseases were primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) (40%), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) (24.3%) and AIH-PBC overlap syndrome (32.9%). Cirrhosis was confirmed by biopsy in 16 patients (22.9%). 15 patients (21.4%) had an APRI index >2 (Cirrhosis) and only six met both criteria. The AUC of the APRI was 0.77 (95% CI 0.65−0.88). The degree of concordance between the tests was low for an APRI cut-off point >2 (kappa 0.213; 95% CI 0.094−0.332), as well as for cut-off points >1.5, >1 and >0.5 (kappa 0.213, 0.255, 0.257, respectively)

ConclusionOur results suggest that there is little concordance between APRI and liver biopsy for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ALD. It should therefore not be used as a single diagnostic method to determine cirrhosis.

Se ha propuesto que métodos no invasivos pueden remplazar la biopsia hepática en el diagnóstico del daño tisular en pacientes con hepatopatía autoinmune (EHA). Este estudio evalúa el rendimiento diagnóstico y grado de concordancia entre el índice Ast to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) y la biopsia hepática en el diagnóstico de cirrosis en estos pacientes.

Material y métodosEn una cohorte de pacientes con EHA se determinó el valor del índice APRI y los resultados de la biopsia hepática según la escala METAVIR. Se evaluó el área bajo la curva (AUC) y la concordancia entre un valor de APRI > 2 y un puntaje METAVIR F4 como marcadores de la presencia de cirrosis hepática mediante un estadístico de kappa.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 70 pacientes (51 ± 13 años). Las hepatopatías autoinmunes más frecuentes fueron la cirrosis biliar primaria (CBP) (40%), Hepatitis autoinmune (HAI) (24,3%) y el síndrome de sobreposición HAI–CBP (32,9%). Se confirmó cirrosis por biopsia en 16 pacientes (22,9%); 15 pacientes (21,4%) presentaron índice APRI > 2 (cirrosis) y solo seis cumplieron ambos criterios. El AUC del APRI fue de 0,77 (IC 95% 0,65−0,88). La concordancia entre las pruebas fue baja para un punto de corte APRI > 2 (kappa 0,213; IC 95% 0,094−0,332), o para puntos de corte > 1,5, > 1 o > 0,5 (kappa 0,213, 0,255, 0,257, respectivamente).

ConclusionesNuestros resultados sugieren que existe un pobre acuerdo entre el resultado del APRI y la biopsia hepática en el diagnóstico de cirrosis en pacientes con EHA, por lo tanto, no se debe utilizar como método diagnóstico único para determinar la presencia de cirrosis.

Autoimmune liver diseases (ALDs), including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and overlap syndromes are chronic diseases that may progress to cirrhosis, liver failure and even death.1–6

The grade of hepatic fibrosis is a measurable prognostic factor in the development of cirrhosis and other liver complications.7–9 For this reason, international guidelines consider the evaluation thereof essential for guiding treatment strategies.1,4,5

Although liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for evaluating tissue damage in patients with chronic liver diseases (CLDs)7–10, it is a costly, invasive procedure with a risk of developing complications.10,11 Moreover, liver biopsy yields a small sample that may not be representative of the grade of hepatic fibrosis7,12, and among pathologists there is a high rate of interobserver variability — as high as 10–20%.8,12 These limitations have spurred the development of various non-invasive methods with a view to achieving early evaluation of hepatic fibrosis.7,11

The most commonly used ones include the aspartate transaminase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI), proposed by Wai et al. It has gained acceptance as it is a simple, non-invasive method based on measuring transaminases and platelet count.12 The APRI proved a good predictor of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis of 80% and 89%, respectively.12,13 However, this diagnostic performance was lower when predicting fibrosis in patients with hepatitis B infection.14

To date, information regarding the performance of the APRI as a predictor of cirrhosis of the liver in patients with ALDs is limited. Therefore, the European guidelines for managing AIH1 say that it is not yet possible to recommend its use, and the American guidelines for managing PSC do not include it in their recommendations for follow-up or management.6 The objectives of this study were to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the APRI for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ALDs and to evaluate concordance between the APRI and liver biopsy as a diagnostic test for cirrhosis in these patients.

Patients and methodsA retrospective analysis was performed with a population consisting of patients with chronic ALDs cared for on an outpatient basis by the Hepatology Department at Hospital Universitario San Ignacio [San Ignacio University Hospital], a leading hospital in Bogotá D.C. (Colombia), between 1 January 2016 and 25 June 2019. Patients over 18 years of age with a diagnosis of an ALD using the criteria established by international consensuses for the diagnosis of AIH1, PBC4, PSC6 or autoimmune overlap syndromes15 were enrolled. The patients enrolled had to have results from blood testing, including transaminases and platelets, performed as close as possible to and no more than a year from the date on which they underwent liver biopsy. Patients not having undergone liver biopsy and patients with cirrhosis of an aetiology other than AIH, PBC or PSC were excluded.

Information was collected regarding each patient's type of liver disease (diagnosis of AIH, PBC or PSC), serology variables for the calculation of the APRI (AST and platelet count), liver panel (alanine transaminase [ALT], alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT], bilirubin, albumin and clotting times), levels of antibodies measured (antinuclear antibodies [ANAs], antimitochondrial antibodies [AMAs], anti-smooth muscle antibodies [ASMAs] and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCAs]), IgG levels and presence or absence of biliary tract stenosis on magnetic resonance cholangiography, as well other autoimmune comorbidities (Sjögren's syndrome, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus) and significant systemic diseases (hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus).

The formula proposed by Wai et al. was used to calculate the APRI. (APRI = [AST level of patient/AST level at upper limit of normal] × 100/platelet count 109/l.) AST and platelet count were determined after biopsy, but before the start of specific management. For the primary analysis, a cut-off point >2 was used as an indicator of a diagnosis of cirrhosis.12

In the liver biopsies, fibrosis was staged according to the METAVIR scale: F0 = no fibrosis; F1 = periportal fibrosis; F2 = incomplete septal fibrosis; F3 = complete septal fibrosis; F4 = histological cirrhosis.16

The sample size was calculated according to Hong’s nomogram15 (assuming a 50% marginal prevalence of cirrhosis in the study population), with a degree of agreement between the two tests under the null hypothesis of 0.9 (90%), accepting a difference between the proportions of acceptable agreement of 0.1 (10%), for a sample size of 70 patients.

The difference between medians of the APRI score according to the grade of fibrosis was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis statistic, taking into account that the data did not fulfil the assumption of normality. Significant differences were determined using a Mann-Whitney U test as a post hoc analysis; a Bonferroni correction was performed, considering that multiple comparisons were made. The area under the ROC curve was determined in order to establish the predictive capacity of the APRI compared to liver biopsy. This test is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis. The concordance between the two tests was evaluated using a simple kappa statistic. The results were interpreted according to Landis and Koch's criteria in the following manner: over 0.8 corresponded to almost perfect agreement, 0.61−0.8 to substantial agreement, 0.41−0.6 to moderate agreement, 0.2−0.4 to fair agreement, and under 0.2 to slight agreement. All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata 15 statistic software package.

As it was a retrospective study, it was not considered necessary to obtain informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee at our institution.

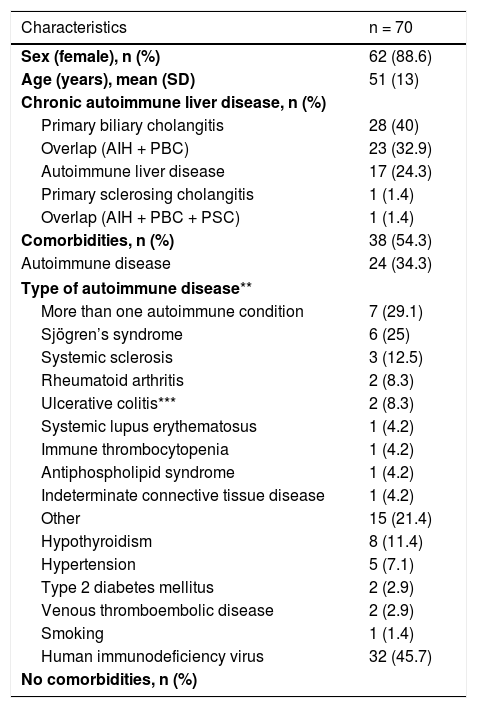

ResultsOf a total of 474 patients managed on an outpatient basis by the Hepatology Department with a diagnosis of an ALD, 70 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were considered in the analysis. The mean age was 51 years (SD ± 13) and the majority were women (88.6%). PBC was the most common ALD, with a total of 28 patients (40%); 24 patients (34.3%) had non-liver autoimmune diseases. In PBC, the most common autoimmune comorbidities were sclerosing diseases (14.3%) and rheumatoid arthritis (7.2%). By contrast, in overlap syndromes (AIH + PBC), the most common comorbidity was Sjögren's syndrome (17.4%). Table 1 shows the patients' clinical and demographic characteristics.

Description of the sample.

| Characteristics | n = 70 |

|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 62 (88.6) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 51 (13) |

| Chronic autoimmune liver disease, n (%) | |

| Primary biliary cholangitis | 28 (40) |

| Overlap (AIH + PBC) | 23 (32.9) |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 17 (24.3) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1 (1.4) |

| Overlap (AIH + PBC + PSC) | 1 (1.4) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 38 (54.3) |

| Autoimmune disease | 24 (34.3) |

| Type of autoimmune disease** | |

| More than one autoimmune condition | 7 (29.1) |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 6 (25) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 3 (12.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (8.3) |

| Ulcerative colitis*** | 2 (8.3) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 (4.2) |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | 1 (4.2) |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 1 (4.2) |

| Indeterminate connective tissue disease | 1 (4.2) |

| Other | 15 (21.4) |

| Hypothyroidism | 8 (11.4) |

| Hypertension | 5 (7.1) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 2 (2.9) |

| Venous thromboembolic disease | 2 (2.9) |

| Smoking | 1 (1.4) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 32 (45.7) |

| No comorbidities, n (%) | |

SD: standard deviation; PBC: primary biliary cholangitis; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; n = sample size; % = percentage.

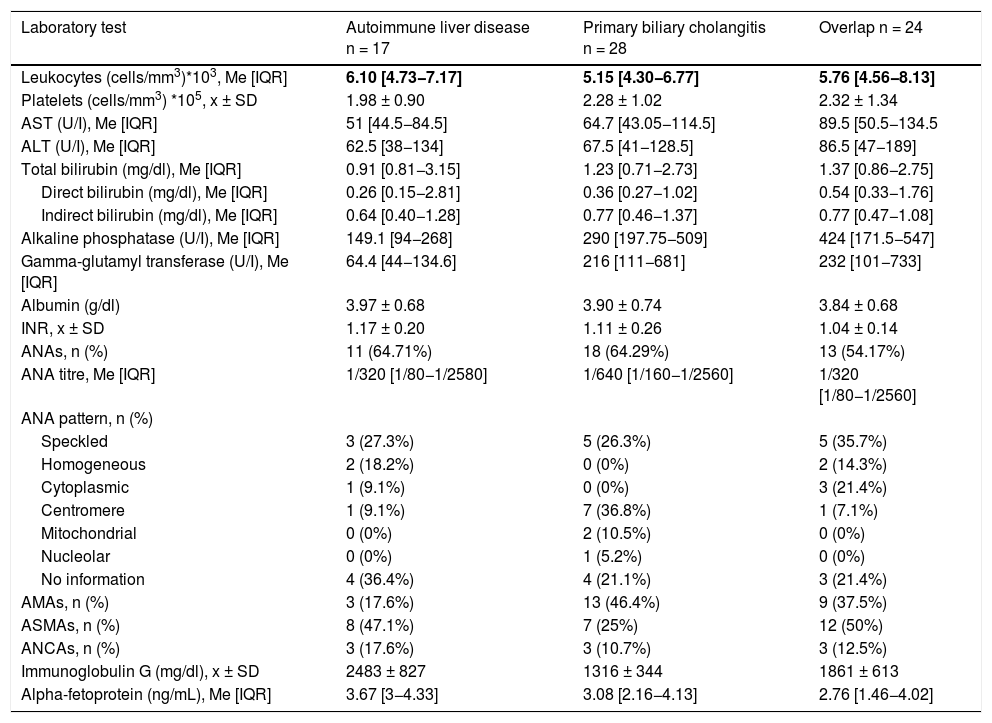

*The two patients with biliary tract stenosis were those who had PSC.

Leukocyte and platelet counts were similar among the different types of chronic ALDs. Transaminase, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels were found to be higher in the autoimmune overlap syndrome group, as well as bilirubin levels, which were also elevated in the PBC group. ANAs and AMAs were positive in more patients in the PBC group (ANAs = 67.9%; AMAs = 46.4%), while ASMAs were positive in more patients in the overlap syndrome and AIH groups (50% and 47.1%, respectively). Regarding ANA patterns, the speckled pattern was the most common in AIH and overlap syndromes, whereas the centromere pattern was the most common in PBC (Table 2).

Laboratory characteristics by type of chronic autoimmune liver disease.

| Laboratory test | Autoimmune liver disease n = 17 | Primary biliary cholangitis n = 28 | Overlap n = 24 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3)*103, Me [IQR] | 6.10 [4.73−7.17] | 5.15 [4.30−6.77] | 5.76 [4.56−8.13] |

| Platelets (cells/mm3) *105, x ± SD | 1.98 ± 0.90 | 2.28 ± 1.02 | 2.32 ± 1.34 |

| AST (U/I), Me [IQR] | 51 [44.5−84.5] | 64.7 [43.05−114.5] | 89.5 [50.5−134.5 |

| ALT (U/I), Me [IQR] | 62.5 [38−134] | 67.5 [41−128.5] | 86.5 [47−189] |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl), Me [IQR] | 0.91 [0.81−3.15] | 1.23 [0.71−2.73] | 1.37 [0.86−2.75] |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl), Me [IQR] | 0.26 [0.15−2.81] | 0.36 [0.27−1.02] | 0.54 [0.33−1.76] |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl), Me [IQR] | 0.64 [0.40−1.28] | 0.77 [0.46−1.37] | 0.77 [0.47−1.08] |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/I), Me [IQR] | 149.1 [94−268] | 290 [197.75−509] | 424 [171.5−547] |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/I), Me [IQR] | 64.4 [44−134.6] | 216 [111−681] | 232 [101−733] |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.97 ± 0.68 | 3.90 ± 0.74 | 3.84 ± 0.68 |

| INR, x ± SD | 1.17 ± 0.20 | 1.11 ± 0.26 | 1.04 ± 0.14 |

| ANAs, n (%) | 11 (64.71%) | 18 (64.29%) | 13 (54.17%) |

| ANA titre, Me [IQR] | 1/320 [1/80−1/2580] | 1/640 [1/160−1/2560] | 1/320 [1/80−1/2560] |

| ANA pattern, n (%) | |||

| Speckled | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (26.3%) | 5 (35.7%) |

| Homogeneous | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| Cytoplasmic | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| Centromere | 1 (9.1%) | 7 (36.8%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Mitochondrial | 0 (0%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nucleolar | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| No information | 4 (36.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| AMAs, n (%) | 3 (17.6%) | 13 (46.4%) | 9 (37.5%) |

| ASMAs, n (%) | 8 (47.1%) | 7 (25%) | 12 (50%) |

| ANCAs, n (%) | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (10.7%) | 3 (12.5%) |

| Immunoglobulin G (mg/dl), x ± SD | 2483 ± 827 | 1316 ± 344 | 1861 ± 613 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL), Me [IQR] | 3.67 [3−4.33] | 3.08 [2.16−4.13] | 2.76 [1.46−4.02] |

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; INR: international normalised ratio; ANAs: antinuclear antibodies; AMAs: antimitochondrial antibodies; ANCAs: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; ASMAs: anti-smooth muscle antibodies.

Me = Median; IQR = interquartile range; x = Mean; SD = standard deviation; n = sample size; % = percentage.

The group of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis featured a single patient which precluded calculations for grouped data.

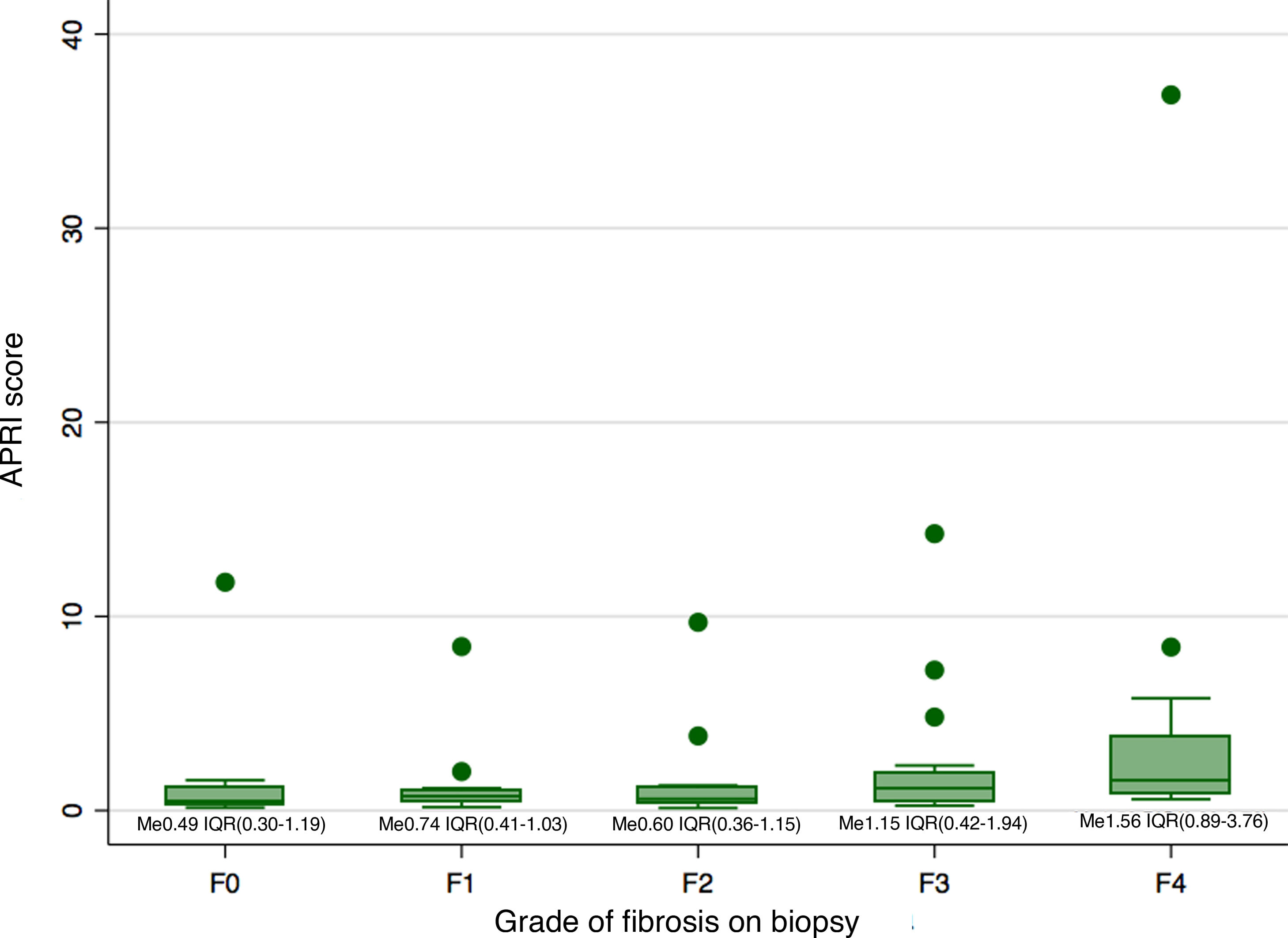

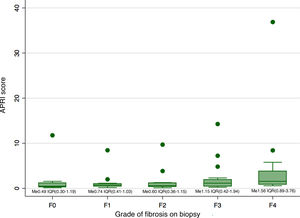

Biopsy confirmed cirrhosis (METAVIR scale F4) in 16 patients (22.9%), complete septal fibrosis (F3) in 16 patients (22.9%), incomplete septal fibrosis (F2) in 14 patients (20%) and periportal fibrosis (F1) in 16 patients (22.9%). The biopsy results of eight patients (11.4%) showed no fibrosis (METAVIR scale F0). Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the APRI scale according to the grade of fibrosis on biopsy. Just six patients had both a METAVIR scale score of F4 and an APRI score higher than 2.

Comparison of the median of the APRI scores between the different categories of fibrosis revealed a difference in the median of at least one pair of results (Kruskal-Wallis 0.0148). This difference was only significant between the categories F4 and F0 (p = 0.02), F4 and F1 (p < 0.01), and F4 and F2 (p < 0.01). However, the differences were not significant after the Bonferroni correction was applied.

Evaluation of the predictive capacity of the APRI as a tool for the detection of cirrhosis in ALDs showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65−0.88). Individual analysis of subgroups by specific disease yielded similar figures: for AIH, the AUC was 0.79 (95% CI 0.52–1); for PBC, it was 0.74 (95% CI 0.55−0.93); and for overlap syndromes, it was 0.84 (95% CI 0.68–1). The sensitivity of the APRI, using a value of 2 as a cut-off point, was 37.5% (95% CI 15.2–64.6 %), and the specificity thereof was 83.3% (95% CI 70.7–92.1 %) (Appendix B, Supplementary Fig. 1). When we selected a cut-off point with both higher sensitivity and higher specificity, we determined a value of 0.835, which had a sensitivity of 87.5% (95% CI 61.7–98.4%) and a specificity of 61.1% (95% CI 46.9–74.1%).

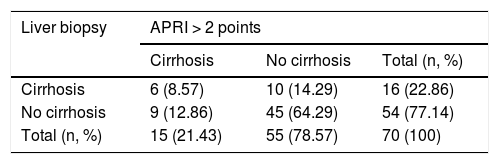

The degree of concordance between the APRI (>2) and the liver biopsy (METAVIR F4), for the total population, was low (kappa 0.213; 95% CI 0.094−0.332; p = 0.07) (Table 3). When we changed the cut-off point for the APRI to a score >1.5 (kappa 0.255; 95% CI 0.137−0.373; p = 0.03), a score >1 (kappa 0.257; 95% CI 0.149−0.365; p = 0.02) or a score >0.5 (kappa 0.253; 95% CI 0.174−0.333; p = 0.001), concordance was also low. The degree of concordance between the APRI (>2) and the liver biopsy (METAVIR F4), within each individual disease, showed kappa values consistently under 0.4.

Kappa coefficient for concordance between APRI and liver biopsy.

| Liver biopsy | APRI > 2 points | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | No cirrhosis | Total (n, %) | |

| Cirrhosis | 6 (8.57) | 10 (14.29) | 16 (22.86) |

| No cirrhosis | 9 (12.86) | 45 (64.29) | 54 (77.14) |

| Total (n, %) | 15 (21.43) | 55 (78.57) | 70 (100) |

Kappa 0.213 (95% CI 0.094−0.332).

This study evaluated the diagnostic performance of the APRI for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ALDs. It enrolled patients with AIH, PBC and overlap syndromes and demonstrated that the APRI has a moderate predictive capacity, moderate specificity and low sensitivity. It also found a low level of agreement between an APRI value >2 and liver biopsy for the diagnosis of cirrhosis (METAVIR F4). These data suggest that these results cannot be considered clinically equivalent in this patient group.

Most patients were women. This was consistent with that reported in other studies, which have shown a predominance of women in most liver diseases (with the exception of PSC, in which a higher frequency of men has been seen) (2–4,6). Within ALDs, PBC was the most common, followed by overlap of AIH/PBC, AIH, PSC and overlap of AIH/PBC/PSC. This was consistent with the reports in the literature.1,6

We found a high frequency of patients with non-liver autoimmune diseases; 29.1% of patients with comorbidities had more than one autoimmune disease, including Sjögren's syndrome, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. This association has been reported in the literature.1,4 The only patient with PSC also had ulcerative colitis, which has a high prevalence in this disease.6

Our data found that the median of the APRI values was slightly higher among patients with cirrhosis (METAVIR F4) compared to patients with no fibrosis or with mild fibrosis (METAVIR F0, F1 or F2). However, this difference was not statistically significant following correction due to multiple comparisons. In addition, an APRI cut-off point of 2 was found to have very low sensitivity (37%) for the diagnosis of cirrhosis — even lower than that reported by Shanshan (70%) in a systematic review that included four prior studies in patients with AIH. This suggests that this cut-off point would detect just a minimal proportion of patients with cirrhosis. Sensitivity was slightly higher with a cut-off point of 0.84, so we suggest this value for patients with ALDs.

In this study, the AUC for the detection of cirrhosis in patients with ALDs was 0.77. This was similar to that reported in prior studies, such as a study conducted by Yuan et al., which reported an AUC of 0.798 (0.69−0.90) for the detection of cirrhosis using the APRI17 in patients with AIH, and other studies conducted in predominantly European and Asian populations.18–20 These findings suggest that the diagnostic capacity of the APRI for the diagnosis of cirrhosis is not different in the Latin American population, even though different clinical behaviour has been reported in this population.21,22 We also found similar AUCs for AIH, PBC and overlap syndromes, suggesting that the operating characteristics of the APRI are similar and equally limited for the different ALDs.

Our results also demonstrated low concordance between the APRI value (with a cut-off point >2) and liver biopsy (METAVIR scale F4) in the diagnosis of cirrhosis in the population of patients with ALDs (kappa 0.213; 95% CI 0.094−0.332; p = 0.07). When the cut-off point for the APRI was decreased to lower values (values previously proposed by other authors), there was still low concordance between these two tests in this group of patients. This suggests that these results cannot be considered clinically equivalent. Similar findings had already been reported by Anastasiou et al., who showed that there was no significant correlation between the APRI and the grade of fibrosis determined on liver biopsy in patients with AIH (Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.163; p value = 0.25).23 These findings support this same conclusion in the other ALDs.

This is the first study that has evaluated the predictive capacity of the APRI in patients with overlap syndromes and the first study that has reported the concordance between a non-invasive serology method and liver biopsy in the diagnosis of cirrhosis in multiple ALDs, showing that their results cannot be considered clinically equivalent. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether combining the APRI with other serology markers (such as the FIB4 score) or with FibroScan improves concordance with biopsy results in these diseases.

Certain limitations should be taken into consideration. Although the sample size was statistically calculated based on the prevalence of patients with ALDs cared for in our practice, the number of patients per subgroup of ALD was relatively small. However, the results were consistent across the different subgroups, supporting the conclusions drawn. In addition, the time lapse between the biopsy procedure and the blood draw ranged from a few days to a year, which might have given rise to a length of time bias. However, in most cases, this time lapse was less than three months, limiting the impact of this risk. Future studies must be conducted which enrol more patients with each individual disease and in which the two tests (biopsy and the APRI) are performed simultaneously to confirm the results of this study.

ConclusionsThe results of this study suggest that there is poor agreement between the APRI result and liver biopsy for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ALDs. In light of the evidence, we believe that it is not possible at present to recommend the use of the APRI as an isolated tool for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in this patient group. Diagnosis must therefore involve the simultaneous use of other non-invasive tests such as elastography.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Suarez-Quintero CY, Patarroyo Henao O, Muñoz-Velandia O. Concordancia entre el resultado de la biopsia hepática y el índice APRI (Ast to Platelet Ratio Index) en el diagnóstico de cirrosis en pacientes con enfermedad hepática autoinmune. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:465–471.