Although the use of non-invasive methods for assessment of liver fibrosis has reduced the need for biopsy, the diagnosis of liver damage still requires histological evaluation in many patients. We aim to describe the indications for percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) and the rate of complications in an outpatient setting over 5 years.

MethodsThis observational, single-center, and retrospective study included patients submitted to real-time ultrasound (US)-guided biopsies from 2015 to 2019. We collected age, gender, coagulation tests, comorbidities, and the number of needle passes. The association between the variables and complications was evaluated using the generalized estimating equations method.

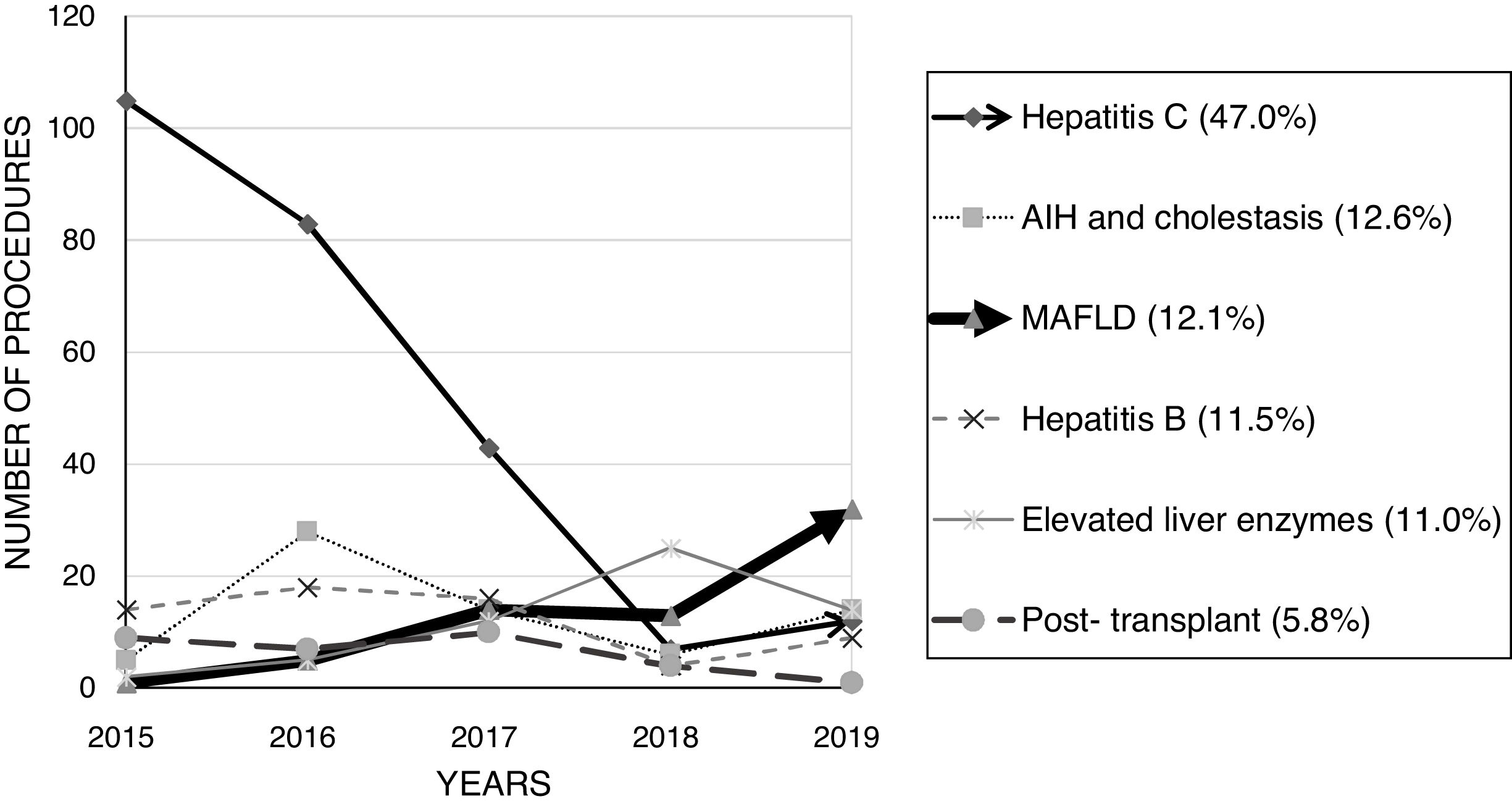

ResultsWe analyzed 532 biopsies in 524 patients (55.3% male) with a median age of 49 years (range 13–74y). An average of 130.3 biopsies per year were performed in the first 3 years of the study versus 70.5 in the other 2y. The main indications were hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (47.0%), autoimmune and cholestatic liver diseases (12.6%), and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) (12.1%). The number of HCV-related biopsies had a remarkable reduction, while MAFLD-related procedures have progressively raised over time. Around 54% of the patients reported pain, which was significantly associated with females (p=0.0143). Serious complications occurred in 11 patients (2.1%) and hospital admission was necessary in 10 cases (1.9%). No patient required surgical approach and there were no deaths. No significant association was found between the studied variables and biopsy-related complications.

ConclusionThe indications for PLB in an outpatient setting have changed from HCV to MAFLD over the years. This procedure is safe and has a low rate of serious complications, but new strategies to prevent the pain are still needed, especially for females.

Aunque el uso de métodos no invasivos para evaluar la fibrosis hepática ha reducido la necesidad de una biopsia, el diagnóstico de daño hepático aún requiere una evaluación histológica en muchos pacientes. Nuestro objetivo es describir las indicaciones de la biopsia hepática percutánea ambulatoria y la tasa de complicaciones durante cinco años.

MétodosEste estudio observacional, retrospectivo y unicéntrico incluyó pacientes sometidos a biopsias guiadas por ecografía en tiempo real desde 2015 hasta 2019. Recogimos información sobre edad, sexo, pruebas de coagulación, comorbilidades y número de pasadas de aguja. La asociación entre variables y complicaciones se evaluó mediante el método de ecuaciones de estimación generalizada.

ResultadosAnalizamos 532 biopsias en 524 pacientes (55,3% hombres) con una edad media de 49 años (rango de 13 a 74 años). Se realizó una media de 130,3 biopsias por año en los primeros tres años del estudio frente a 70,5 en los otros dos años. Las principales indicaciones fueron la infección por el virus de la hepatitis C (HCV) (47,0%), las enfermedades hepáticas autoinmunes y colestásicas (12,6%) y la enfermedad del hígado graso asociada a disfunción metabólica (MAFLD) (12,1%). El número de biopsias relacionadas con la HCV tuvo una reducción notable, mientras que los procedimientos relacionados con MAFLD han aumentado progresivamente con el tiempo. Alrededor del 54% de los pacientes informaron dolor, que se asoció significativamente con las mujeres (p = 0,0143). Se produjeron complicaciones graves en 11 pacientes (2,1%) y el ingreso hospitalario fue necesario en 10 casos (1,9%). Ningún paciente requirió abordaje quirúrgico y no hubo muertes. No se encontró asociación significativa entre las variables estudiadas y las complicaciones relacionadas con la biopsia.

ConclusiónLas indicaciones para la biopsia hepática percutánea ambulatoria han cambiado de HCV a MAFLD con el pasar de los años. Este procedimiento es seguro y tiene una baja tasa de complicaciones graves, pero aún se necesitan nuevas estrategias para prevenir el dolor especialmente en mujeres.

Histological evaluation has a crucial role in diagnosing the etiology and severity of hepatic diseases, liver tumors, and is useful in the follow-up after liver transplantation.1–3 Several routes are available, such as laparoscopic, endoscopic, or transjugular4 but percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) is generally preferable since it is less invasive and less costly compared to other routes.2 Coagulation impairment, low platelets count, ascites, or anatomical changes are also important in this choice.1

Physicians may use three different approaches: palpation/percussion-guided, image-guided, and real-time image-guided, most commonly ultrasound (US). Real-time US guidance seems to reduce the risk of adverse events and this makes PLB safe to perform.2–6 Although the pain has been commonly reported after PLB (20–50%), it is usually mild, self-limited, or has a good response to analgesics.4,7 The incidence of serious complications is low, not exceeding 3%.7–11 Approximately 60% of these events occur within the first 2h and 96% in the 24h following the procedure.12 The reported incidence of bleeding ranges from 0.5 to 1.8%,13 but it can be serious and lead to death if prompt treatment is not carried out.1,12

In recent years, the main indication for PLB in adults has been the evaluation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, either to exclude other etiologies of hepatic damage or to establish the histological stage of fibrosis and set the appropriate therapy.14 However, that need has been reducing in the era of direct-acting antiviral drugs11 and non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis, such as biochemical markers and elastography.14

There is a lack of data on the need for PLB in Brazil in the era of non-invasive methods to assess liver fibrosis. We aim to describe the indications, as well as the rate of biopsy-related complications in a 5-year study.

MethodsThis observational, retrospective, and single-center study involved individuals submitted to outpatient PLB from January 2015 to December 2019 at the Gastrocentro of the University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil. Patients were eligible according to a database record and subsequently, analysis of manual and electronic medical records was conducted. The protocol was analyzed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Campinas (Unicamp) (CAAE: 29553819.9.0000.5404). An informed consent term was applied to the patients who were still on follow-up at our center.

Inclusion criteria: patients>12 years old submitted to US-guided PLB at the Gastrocentro (Unicamp) during the study period. Exclusion criteria: those with incomplete data in the medical records. We analyzed gender, age, comorbidities, platelets count, INR (international normalized ratio), indication for the biopsy, number of needle passes, as well as PLB-related complications. Patients submitted to more than one PLB were considered as a new case.

The indications for PLB were classified as follows: HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), autoimmune and cholestatic liver diseases, elevated liver enzymes, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), and post-transplant follow-up. Other indications, such as suspicion of drug-induced liver injury, were classified as elevated liver enzymes.

The patients’ comorbidities were classified as (1) metabolic: high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity; (2) chronic kidney disease, (3) neuropsychiatric disorders, (4) other, as described in the medical records. Patients could be inserted into more than one group of comorbidities.

All the procedures were performed in a real-time US-guided setting and the operator was a senior resident supervised by a hepatologist. A low dose of intravenous midazolam (2–3mg) was usually administered. Local anesthesia was performed with lidocaine 2% after skin sterilization. A Tru-cut 14G needle was used preferably in the right hepatic lobe accessing through intercostal spaces and the number of needle passes depended on the operator's decision. Patients remained on complete rest and fasting in a comfortable position, under the monitoring of vital signs, and were discharged after 4–6h. They were instructed to return in case of severe pain in the abdomen, chest or at the puncture site, dizziness, fainting, nausea, vomiting, or dyspnea.

The PLB-related consequences were divided as follows: (1) pain: complained by the patient at the puncture site, on the right shoulder, thorax, or abdomen. (2) Serious complications: perihepatic fluid on ultrasound, subcapsular bleeding, right-sided hemothorax, and death.

Statistical analysisThe Generalized Estimating Equations method was used to evaluate the association between the variables and pain or complications. The estimates were calculated by maximum likelihood in order to avoid bias on the difference in the number of biopsies for each patient. Observations within a given patient were not independent and intra-patient correlation and variations were introduced into the analysis using a mixed generalized linear model. A Generalized Estimating Equations method can potentially allow for better between-group comparisons by controlling the variance introduced into the data by repeated measures (i.e., clustering) from a single participant in a data set.

The Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney test for numerical variables. Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS for Windows version 9.4 system. The level of statistical significance adopted in the analysis was 5%.

ResultsA total of 569 biopsies were performed during the study period. Due to a lack of data in the medical records, 37 cases were excluded. Eight subjects underwent two biopsies, so the study involved 532 biopsies in 524 patients (55.3% male) with a median age of 49 years (range: 13 to 74), as shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients submitted to percutaneous liver biopsies.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male sex (n=532) | 294 (55.3%) |

| Median age, years (range) | 49 (13–74) |

| INR (n=530) | |

| ≤1.2 | 505 (95.3%) |

| >1.2 | 25 (4.7%) |

| Platelets count (n=530) | |

| ≤75,000/mm3 | 6 (1.1%) |

| >75,000–120,000/mm3 | 27 (5.1%) |

| >120,000/mm3 | 497 (93.8%) |

| Comorbidities (n=532) | |

| None | 273 (51.3%) |

| Metabolic | 304 (57.1) |

| Overweight or obesity | 97 (18.2%) |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | 14 (2.6%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (2.1%) |

| Other | 30 (5.6%) |

INR: international normalized ratio.

Regarding laboratory tests, INR value and platelets count were available in 530 procedures. The median and range (minimal–maximum) were 1.01 (0.84–1.55) and 200,000/mm3 (48,000–474,000/mm3. Almost 57% had metabolic comorbidities, around 18% had overweight or obesity and 2.1% had chronic kidney disease. Half of the studied population had no comorbidities (Table 1).

In general, the number of biopsies reduced over time, as 391 procedures (73.5%) were performed in the first 3 years (average of 130.3 biopsies per year versus 70.5 in the last 2 years). HCV infection assessment was the major indication for PLB (47.0%), followed by autoimmune and cholestatic liver diseases (12.6%) and MAFLD (12.1%). The amount of HCV-related procedures has sharply reduced. On the other hand, the number of MAFLD-related biopsies has progressively raised over the years, as shown in Fig. 1.

Number of indications-related liver biopsies from 2015 to 2019. There was a remarkable reduction in the number of hepatitis C-related biopsies over the years, while the number of MAFLD-related procedures has progressively increased. AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; MAFLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.

The median number of needle passes was 1 (ranging from 1 to 4). PLB-related pain was reported in 53.6% of the studied population. The female gender was associated with a higher complaint of pain (p=0.0143). There was no significant influence of other clinical and laboratory variables in the occurrence of pain (age, comorbidities, platelets count, INR, and number of needle passes). We analyzed separately obesity/overweight, neuropsychiatric disrorders, and chronic kidney disease, as they are supposedly at higher risk of complications (anatomical changes, insufficient hemostasis or lack of control of respiratory movements).

Serious complications were reported in 11 cases (2.1%): 5 patients had perihepatic fluid on US, 4 had subcapsular bleeding, and 2 had right-sided hemothorax. Ten patients (1.9%) were admitted to the hospital. No one patient required surgical treatment and there were no deaths, as shown in Table 2. There was no association between the occurrence of complications and the studied variables. Renal function was normal in all the patients that developed bleeding.

DiscussionIn this study, we evaluated a large sample of subjects submitted to real-time US-guided PLB in an outpatient setting over 5 years. Viral hepatitis was the main indication for biopsy, similar to previous reports,15,16 especially HCV chronic infection. Post-transplant follow-up was the most common reason for PLB at transplant centers.17 In the pediatric population, the major reported indications were elevated liver enzymes, autoimmune and cholestatic liver diseases.18

The indication for PLB has changed over the years. It was possible to notice a remarkable drop in the amount of HCV-related procedures and a progressive increase in MAFLD-related biopsies. A reduction in the number of biopsies due to HCV was expected, however other liver diseases still require histological evaluation to help on the management and follow-up1 – notably, autoimmune hepatitis, small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis, anti-mitochondrial antibody – negative primary biliary cholangitis, drug- or herb-induced liver injuries, some HBV patients, systemic diseases with hepatic involvement, and MAFLD, which is being intensely studied. As promising therapies are awaited,7 it is feasible to predict that histological staging will help physicians in choosing the best approach to patients with MAFLD.

Although the practice of liver biopsy is subject to criticism in the era of non-invasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis, new histological scoring systems have been proposed to optimize the diagnosis of MAFLD.19 Non-invasive tools are more accurate to predict advanced fibrosis7,20 and there is no single threshold with the perfect balance between sensitivity and specificity. In addition, there is a lack of inflammation assessment, which also limits the usefulness of these methods in daily practice.7,11,14

Of course not all patients with MAFLD need to undergo liver biopsy, but this procedure should be considered in those with unreliable non-invasive evaluation or with suspected active inflammation.7,19,20 Histological assessment provides specific data on the severity of fibrosis, ballooning and inflammation, and it can also diagnose other overlapping liver diseases, especially drug- or herb-induced injuries.7,19 We must remind that the prevalence of MAFLD is increasing worldwide and it is currently the leading indication for liver transplant in some countries.7,21 It is essential to early select patients who need a therapeutic approach before the progression to cirrhosis.7

As supposed, the pain was the most frequent consequence of PLB.1,12,18 A study involving 54 patients described an 84% incidence of pain immediately following the PLB and 39% of the patients still complained of pain after 24h.15 This symptom was associated with anxiety pre-procedure and the female gender.15 We found a 53.6% incidence of pain and a significant association with the female gender but we have not studied patients’ complaints prior to the biopsy. Although pain is generally mild and has a good response to analgesics, local anesthetics do not seem to prevent it, instead of the use of midazolam or nitrous oxide.15 The real-time image-guided setting may reduce the incidence of pain, as it provides anatomical ascertain, reducing trauma to the subcutaneous tissue and hepatic capsule.4,16,17 In our sample, only one patient reported severe pain, requiring hospital admission.

The rate of bleeding was also low in our study, similar to the literature.3,4,22 It has already been described that patients older than 50 years are more likely to progress with bleeding,23,24 but no statistical association between age and hemorrhage was found in our study. Parente et al.9 reported a higher rate of bleeding after liver biopsies (2.3%); however, the studied population had neoplasia, which is more susceptible to hemorrhage. A higher risk of bleeding is also expected in patients with platelets count<50,000–70,000/mm3 and/or INR>1.3–1.5.3,11,23–25 Most of our patients had normal INR and platelets count and there was no bleeding in the subjects with tests out of these limits, so we did not find any association between coagulation tests and bleeding.

The need for hospital admission in our sample (1.9%) was similar to previous reports, ranging from 1 to 3%.3,4,18,23 In addition, there were no more serious complications, such as perforation of the gallbladder, colon, kidneys, hemobilia, abscess, and intraperitoneal bleeding. Death following a PLB is extremely rare (up to 0.1%)1,23 and it did not occur in our study. However, it is essential to notice that, in general, serious complications and death are more frequent in patients with severe comorbidities, suspected neoplasia, and cirrhosis, and such individuals usually undergo in-hospital biopsies at our center.

It is not entirely proven but real-time US guidance seems to reduce the risk of PLB-related serious complications.1,3,23–27 Other factors must be reminded in order to improve the safety of PLB, such as the operator experience11 and a careful selection of individuals to undergo it in an outpatient setting. Our results showed a low incidence of serious complications, even in a scenario of senior residents in training, supervised by a hepatologist.

This study has some limitations: (1) the single-center design may be associated with bias on patients selection, (2) the retrospective design and non-uniform descriptions in the medical records may have changed the rate of complications, (3) the data collected exclusively from the medical records may have missed outcomes of patients eventually admitted to other hospitals, and (4) a non-standardized dose of midazolam for sedation may have affected the incidence of pain.

ConclusionsThe indications for PLB in an outpatient setting are undergoing a notable transition, where HCV infection has been replaced by MAFLD. This procedure is safely performed with real-time ultrasound guidance and has a low rate of serious complications, but new strategies to prevent the pain are still needed, especially for females.

Authors’ contributionMCS: designed the study, assisted liver biopsies, wrote and reviewed the manuscript; LDT, MFF: performed liver biopsies, collected data and wrote the manuscript; MCGM, TMLS: collected data; AY, LTM: performed liver biopsies and reviewed the manuscript; LBEC: provided pathological results; DFM, TSP: reviewed the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone.