The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the presence and impact of Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, physical and psychological disturbances on patients’ QoL after sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS).

MethodsA prospective, observational, cross-sectional, comparative study was carried-out. GI symptoms and patients’ QoL were evaluated by the SF-36 questionnaire and the GI quality of life index (GIQLI). Correlation between GI symptoms, psychological disturbances and QoL scores was analysed.

Results95 patients were included (mean age 50.5 years, range 22–70; 76 females). Presence of GI symptoms was a consistent finding in all patients, and postprandial fullness, abdominal distention and flatulence had a negative impact on patients’ QoL. Patients after SG showed a worsening of their initial psychological condition and the lowest QoL scores. Patients after RYGB showed the best GI symptoms-related QoL.

ConclusionsBoth restrictive and malabsorptive bariatric surgical procedures are associated with GI symptoms negatively affecting patients’ QoL. Compared to SG and BPD/DS, patients after RYGB showed the best GI symptoms-related QoL, which can be used as additional information to help in the clinical decision making of the bariatric procedure to be performed.

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar y comparar la presencia e impacto de los síntomas gastrointestinales (GI), los cambios físicos y psicológicos en la calidad de vida (CV) de los pacientes sometidos a tubulación gástrica (TG), bypass gástrico en Y de Roux (BGYR) y derivación biliopancreática con cruce duodenal (DBP/CD).

MétodosSe realizó un estudio prospectivo, observacional, transversal y comparativo. Los síntomas gastrointestinales y la CV de los pacientes fueron evaluados mediante el cuestionario SF-36 y el índice gastrointestinal de calidad de vida (GIQLI). Se analizó la relación entre los síntomas gastrointestinales, los trastornos psicológicos y las puntuaciones de CV.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 95 pacientes (edad media: 50,5 años, rango: 22-70; 76 mujeres). La presencia de síntomas gastrointestinales fue un hallazgo constante en todos los pacientes, y la pesadez posprandial, la distensión abdominal y la flatulencia tuvieron un impacto negativo en la CV de los pacientes. Los pacientes después de la TG mostraron un empeoramiento de su estado psicológico inicial y unas puntuaciones más bajas en la CV. Los pacientes después del BGYR presentaron la mejor CV relacionada con los síntomas gastrointestinales.

ConclusionesLos procedimientos de cirugía bariátrica tanto restrictivos como malabsortivos se asocian a síntomas GI que afectan negativamente la CV de los pacientes. En comparación con la TG y la DBP/CD, los pacientes tras el BGYR presentaron la mejor CV relacionada con los síntomas GI, lo que puede utilizarse como información adicional para ayudar en la toma de decisiones clínicas sobre el procedimiento bariátrico a realizar.

Obesity is a chronic multifactorial disease associated with significant physical and psychological burden. More than 80% of obese patients suffer from metabolic syndrome (dyslipidaemia, impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes and arterial hypertension) leading to a high cardiovascular risk.1,2 Bariatric surgery induces significant weight loss and is an effective treatment for obesity-related disorders.3,4 The International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) submitted data from 51 different countries with 394,431 bariatric surgical procedures performed since 2014.5 According to it, sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) are currently the most frequently performed procedures, whereas biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) is less frequently reported.

Gastrointestinal (GI) anatomical changes after bariatric surgery may lead to relevant GI symptoms, such as abdominal pain, early satiety, postprandial fullness, abdominal distention, bloating, flatulence, and disturbed bowel habit, that may have a significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL).6,7

The North American Health Institute recommended in 1991 the development of validated tools to monitor the expectations of patients regarding psychosocial changes and their experiences during the periods of weight loss and maintenance after different surgical procedures.8 SF-36 is an internationally renowned multidimensional tool that evaluates the domains of functional capacity, physical aspects, pain, and general state of health, vitality, social aspects, emotional aspects, and mental health.9 SF-36 was developed for generic health-related QoL evaluation, and it enables incorporating the opinion of patients into clinical decision-making.10 GI QoL index (GIQLI) is a well-validated tool for assessing the specific QoL and GI symptoms in patients with GI diseases.11 This questionnaire has been additionally used in the context of GI surgery for gastric cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, achalasia, obesity, and other diseases like diabetes.12

Although satisfaction with weight loss after surgery may outweigh the negative impact of other factors, the development of GI symptoms after bariatric surgery may affect patients’ QoL.13 Despite a higher incidence of GI symptoms and complications after BPD/DS, no significant differences in QoL have been reported between patients after SG, RYGB and BPD/DS by using the Multidimensional Anxiety Questionnaire (MAQ).7,14 However, MAQ may not be the optimal tool, and be less appropriate than SF-36 and GIQLI to evaluate this association.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between QoL and GI symptoms, physical and psychological disturbances in patients after different bariatric surgical procedures. In addition, the impact of bariatric surgery on QoL and GI, physical and psychological burden was compared in patients after different surgical procedures.

Patients and methodsDesign of the studyA prospective, observational, cross-sectional, single centre, comparative study was designed. Patients older than 18 years, who underwent bariatric surgery for morbid obesity, either RYGB, SG or BPD/DS, between January 2001 and December 2016 were considered for inclusion.

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) that included endocrinologists, bariatric surgeons, psychologists, psychiatrists and anaesthetists made the decision on the surgical procedure to be performed in each patient. All procedures were performed by two experienced bariatric surgeons.

Previous GI or pancreatic surgery, other types of bariatric surgery, chronic GI diseases (celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetic gastroparesis), any severe concomitant disease limiting life expectancy, and inability or refusal to perform the study-related procedures or to sign the written informed consent were considered as exclusion criteria.

Demographic data, comorbidities (diabetes, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS), arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia), anthropometry (weight loss and change in body mass index – BMI–), time after surgery, GI symptoms and signs, and psychological disorders (anxiety/depression) were evaluated and recorded at inclusion. Pre-operative comorbidities were recorded retrospectively from the electronic medical records.

Weight loss was defined as the difference between the greatest preoperative weight and the weight at the time of the study. The percentage of excess BMI loss (%EBMIL) was calculated using the formula (preoperative BMI−BMI at inclusion)×100/(preoperative BMI−25). Time after surgery was defined as the time (months) from surgery to inclusion in the study. Psychological disorders were evaluated before and during follow-up after surgery by a dedicated psychologist. For the purposes of the study, depression and anxiety were considered as related to surgery if newly diagnosed or if gotten worse during the follow-up after surgery.

Surgical proceduresRYGB and BPD/DS were routinely performed at our institution in morbid obese patients. The RYGB procedure was performed with a 100–150cm Roux-limb and a 50cm biliary limb. In the BPD/DS procedure, duodenum was divided distal to the pylorus and a sleeve gastrectomy was performed. A retrocolic duodeno-ileostomy was constructed with a 150cm alimentary limb and a 100cm common limb. The remaining small bowel formed the biliary limb. SG was performed following standard procedures and removing about 75% of the stomach.

QoL evaluationQoL was evaluated by both the GIQLI and the SF-36 questionnaires. The GIQLI is a 36-item patient reported outcomes instrument designed to assess GI specific health-related QoL in clinical practice and clinical trials of patients with GI disorders.11 It consists of five domains (GI symptoms, emotion, physical function, social function, and medical treatment). Each item is scored from 0 to 4 and the total GIQLI score ranges from 0 to 144. Higher scores are related to better GI health related QoL.

The SF-36 is a brief psychometric QoL measure of eight health dimensions that has been considered the method of choice in obesity research by the United States Task Force on Developing Obesity Outcomes and Learning Standards.15

GI symptoms and signsGI symptoms including abdominal pain, early satiety, postprandial fullness, gas bloating, abdominal distention and flatulence were recorded and scored as none, mild, moderate and severe. For the purposes of the study, abdominal symptoms were considered as related to surgery if they newly developed or got worse during follow-up after surgery. Stool characteristics were recorded by using a 7-day Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) diary. This tool has been validated and has been shown to correlate with the intestinal transit time.16–18

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are shown as absolute numbers and percentages and were compared using χ2 test or Fischer's exact test as appropriate. Continuous data are presented as mean±SD or median and range for normally or non-normally distributed data, respectively. Normally distributed continuous variables were analysed by the Student-t test, and non-normally distributed variables by the Mann–Whitney U-test when comparing two groups. Normally distributed continuous variables were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and non-normally distributed variables by the Kruskal–Wallis test when comparing more than two groups. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength and direction of the association between two variables. GIQLI and SF-36 scores obtained in the study population were compared with the standard scores reported for the Spanish population.19

Linear regression analysis was used to test any potential association between time from surgery and GI symptoms. Comparisons with a p-value<0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee with the approval number AD-04-014. All patients provided written informed consent to the study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, its amendments, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

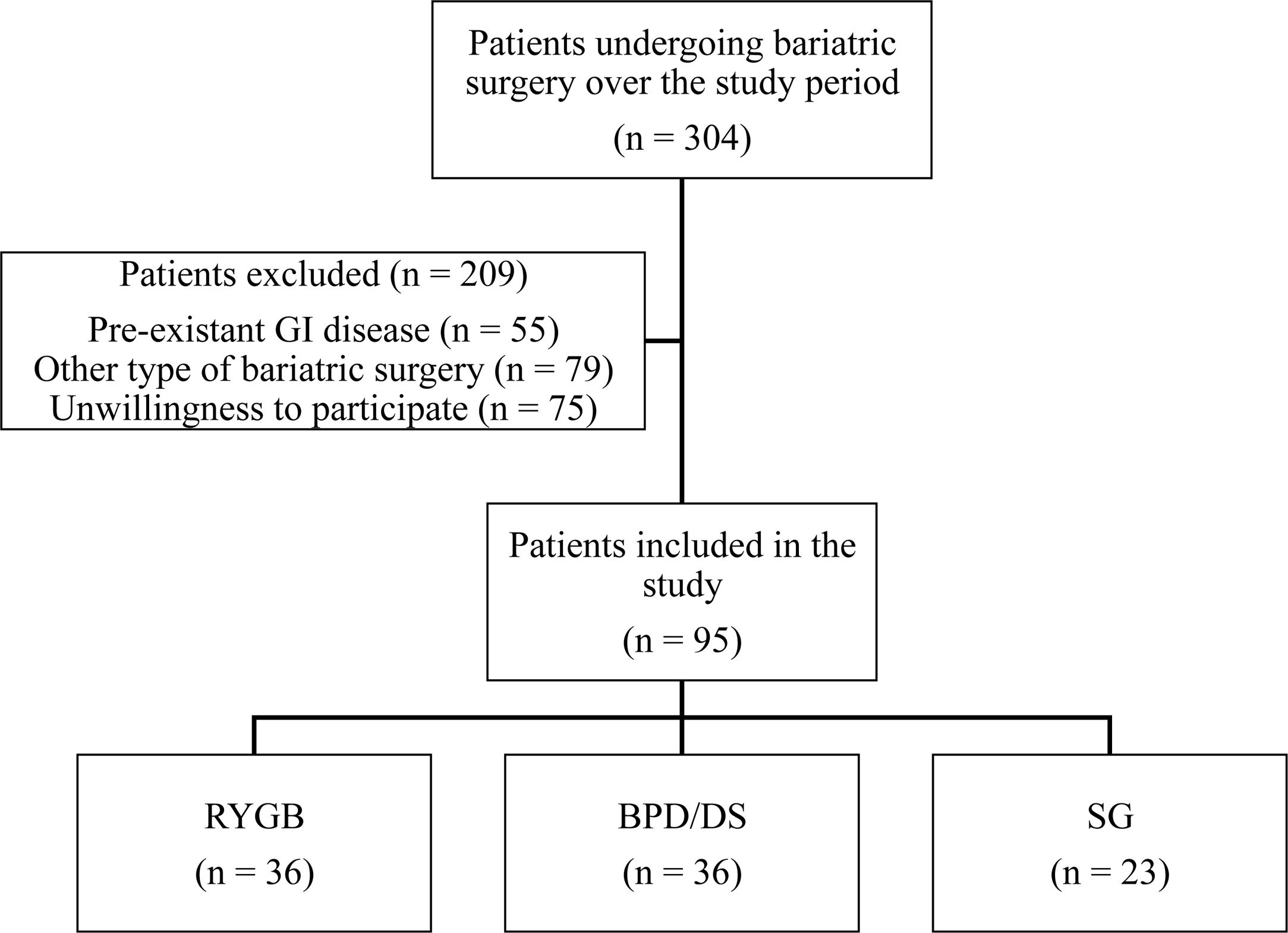

ResultsA total of 304 patients underwent bariatric surgery over the study period and were evaluated. 209 patients were excluded due to the presence of other GI diseases (n=55), other bariatric surgical procedure (n=79) or unwillingness to participate in the study (n=75). Finally, 95 patients were included (Fig. 1). Mean age was 50.5 years (range 22–70 years); 76 patients were female (80%); 36 patients had undergone RYGB (37.9%), 36 patients BPD/DS (37.9%) and 23 patients SG (24.2%). The three groups of patients were similar in terms of age and gender distribution (Table 1). Mean time from bariatric surgery to inclusion into the study was of 62±45.9 months, longer after BPD/DS (86.6±56.9 months) than after RYGB (48.8±30.1 months) or SG (44.2±28.1 months) (p<0.01) (Table 1).

Demographics, clinical features and comorbidities of the patients included in the study according to the bariatric surgical procedure performed.

| Preoperative features | Postoperative features | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGBn=36 | BPD/DSn=36 | SGn=23 | pa value | RYGBn=36 | BPD/DSn=36 | SGn=23 | pb value | |

| Femaleno. (%) | 28 (77.8) | 29 (80.6) | 19 (82.6) | 0.9 | – | – | – | – |

| Age (years) | 51.9±10.4 | 49.5±10.2 | 49.7±11.9 | 0.58 | – | – | – | – |

| Time after surgery (months) | 48.8±30.1 | 86.6±56.9 | 44.2±28.1 | <0.01 | – | – | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | 121.9±21.1 | 145.7±28.5 | 136.9±33.2 | <0.01 | 81.5±14.1 | 87±19.4 | 100.2±25.2 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 46.9±6.3 | 56.7±8.5 | 53.1±11.3 | <0.01 | 31.4±5 | 34±7.7 | 39.1±10.1 | <0.01 |

| Diabetesno. (%) | 10 (27.8) | 13 (36.1) | 8 (34.8) | 0.73 | 0 (0%) | 4 (11.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | <0.01 |

| Hypertensionno. (%) | 12 (33.3) | 11 (30.6) | 5 (21.7) | 0.63 | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.6 |

| OSASno. (%) | 18 (50) | 17 (47.2) | 11 (47.8) | 0.97 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.47 |

| Dyslipidaemiano. (%) | 9 (25) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (4.3) | 0.1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | . |

RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BDP/DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; BMI, body max index; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Mean preoperative BMI was 52.1±9.5kg/m2 and mean body weight 134.6±28.9kg, lower in those patients who underwent RYGB than in those who underwent BPD/DS or SG (p<0.01) (Table 1). Mean weight loss after surgery was 46.5±42kg, greater after BPD/DS (58.7±26.3kg) compared to RYGB (40.4±14.9kg) and SG (36.7±23.8kg) (p<0.01) (Table 1). The %EBMIL after the two malabsorptive procedures was similar (72.4±19.18% after RYGB and 71.7±22.25% after BPD/DS, p=0.69) and greater than after SG (50.7±22.44%, p<0.01).

Prevalence of obesity-related comorbidities before surgery was similar among groups (Table 1). Diabetes resolved in most patients after malabsorptive surgical procedures but only in half of the patients who underwent SG (p<0.01). Arterial hypertension, OSAS and dyslipidaemia resolved in most of the patients after bariatric surgery regardless of the surgical procedure performed (Table 1).

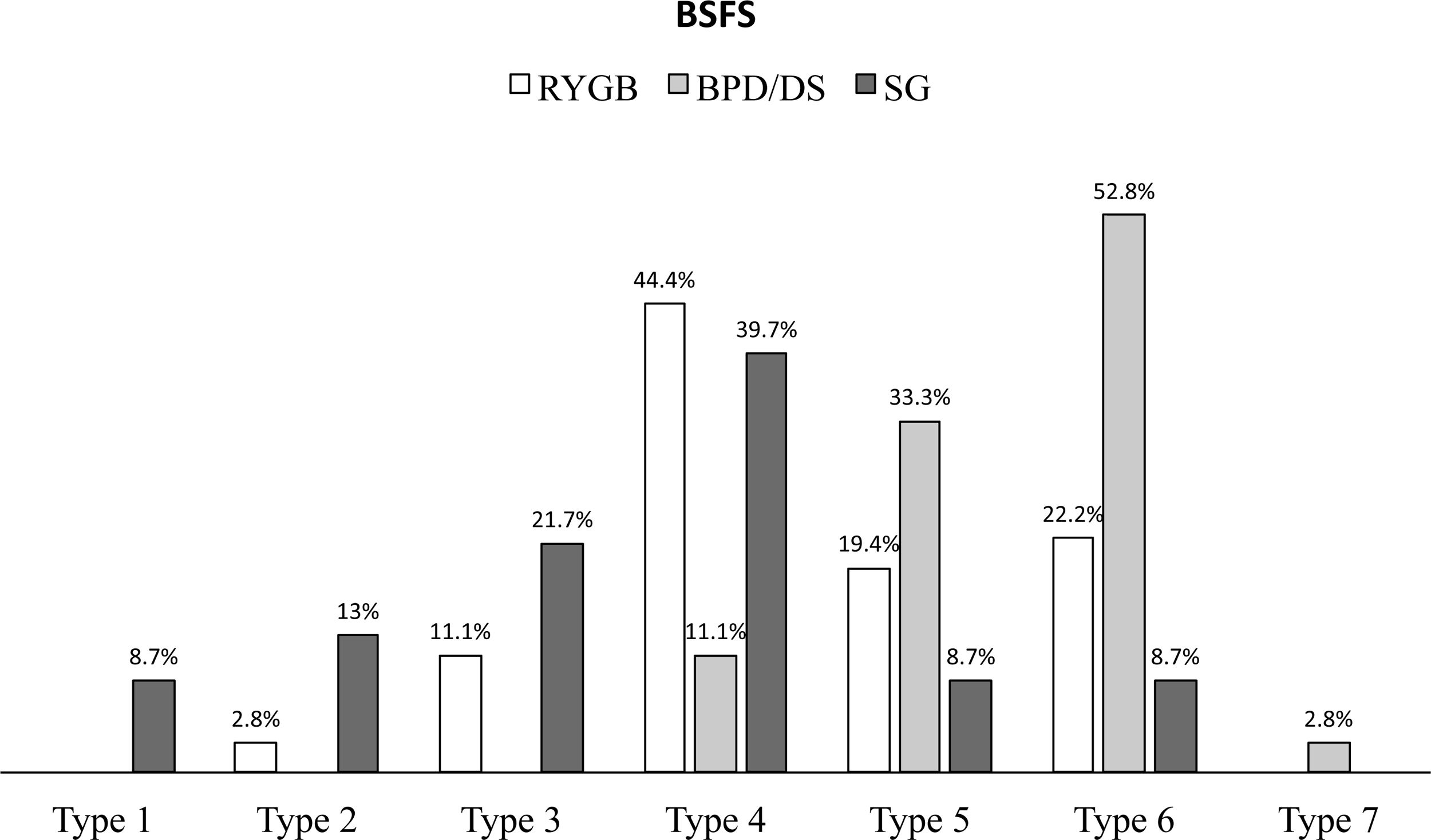

GI symptoms, and psychological disturbancesNo patient was symptom free at the time of inclusion in the study. Fifty-one patients (53.7%) referred soft stools (BSFS 5–7), more often those who underwent BPD/DS than those who underwent RYGB or SG (p<0.01) (Fig. 2). Compared to patients after SG, patients after malabsorptive surgery referred more often bloating (77.8% vs 56.5%, p<0.05) (Table 2). Early satiety was a consistent finding in most patients, but it was significantly less frequent in patients who underwent BPD/DS (86.1% vs 98.3%, p<0.02). Other GI symptoms were less frequently reported and were independent of the surgical procedure performed (Table 2).

Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological disturbances after RYGB, BPD/DS and SG.

| Surgical procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TotalN=95 | RYGBn=36 | BPD/DSn=36 | SGn=23 | p value | |

| Abdominal painno. (%) | 21 (22.1) | 8 (22.2) | 9 (25) | 4 (17.4) | 0.79 |

| Abdominal distensionno. (%) | 34 (35.8) | 12 (33.3) | 12 (33.3) | 10 (43.5) | 0.68 |

| Postprandial fullnessno. (%) | 57 (60) | 21 (58.3) | 21 (58.3) | 15 (65.2) | 0.84 |

| Early satietyno. (%) | 90 (94.7) | 35 (97.2) | 31 (86.1) | 23 (100) | 0.06 |

| Gas bloatingno. (%) | 69 (72.3) | 27 (75) | 29 (80.6) | 13 (56.5) | 0.12 |

| Flatulenceno. (%) | 46 (48.4) | 17 (47.2) | 16 (44.4) | 13 (56.5) | 0.65 |

| Psychological disturbancesno. (%) | 39 (41.1) | 10 (27.8) | 14 (38.9) | 15 (65.2) | 0.02 |

RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BDP/DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

GI symptoms were independent of mean weight loss and %EBMIL, except patients with bloating, who had greater %EBMIL (69.7±22.46% vs 59.37±22.72, p<0.05).

A worsening of their initial psychological condition (depression or anxiety) was present in 41.1% of the patients after surgery, more frequently in those who underwent SG than in those after RYGB or BPD/DS (p<0.01) (Table 2).

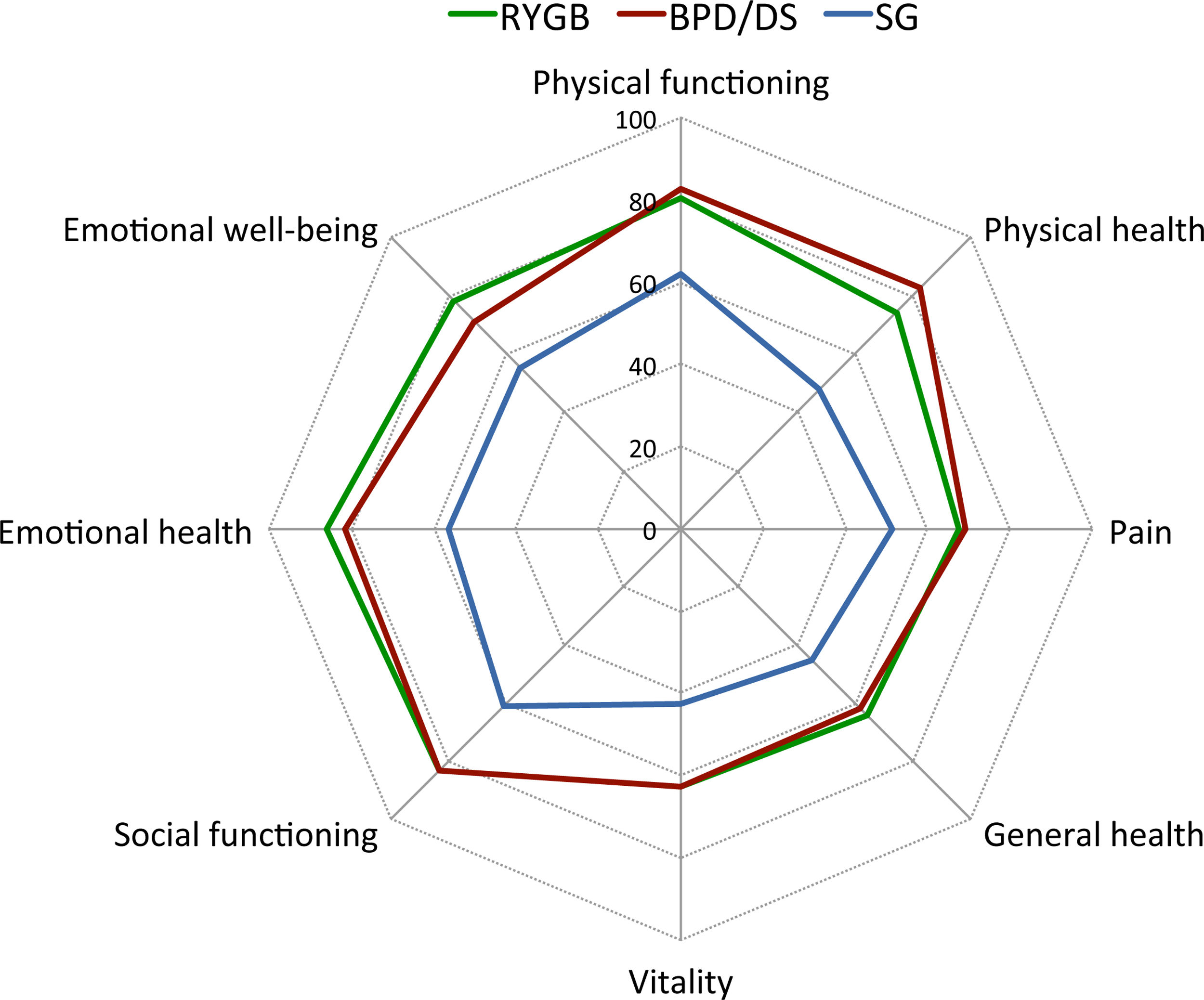

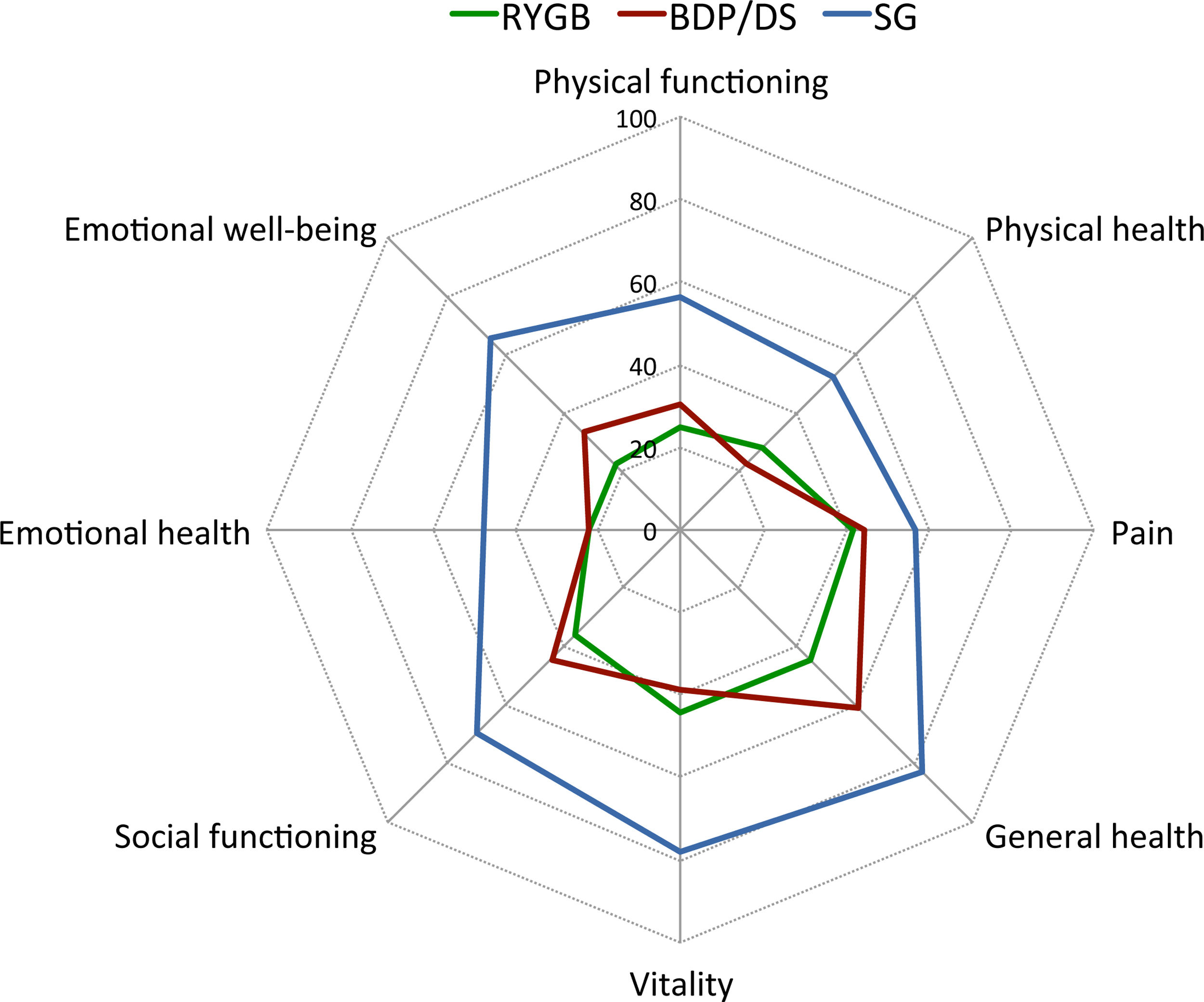

Quality of lifeQoL as evaluated by the SF-36 questionnaire was significantly worse in patients after SG (mean score 54.2±24.1) compared with RYGB (mean score 73.1±22.3) and BPD/DS (mean score 73.9±15) (p<0.01) (Fig. 3). The prevalence of patients with a poor QoL, defined as an abnormally low SF-36 score as compared to the general population, was significantly greater in patients after SG than in those after RYGB or BPD/DS in all dimensions except in pain and emotional health (Fig. 4).

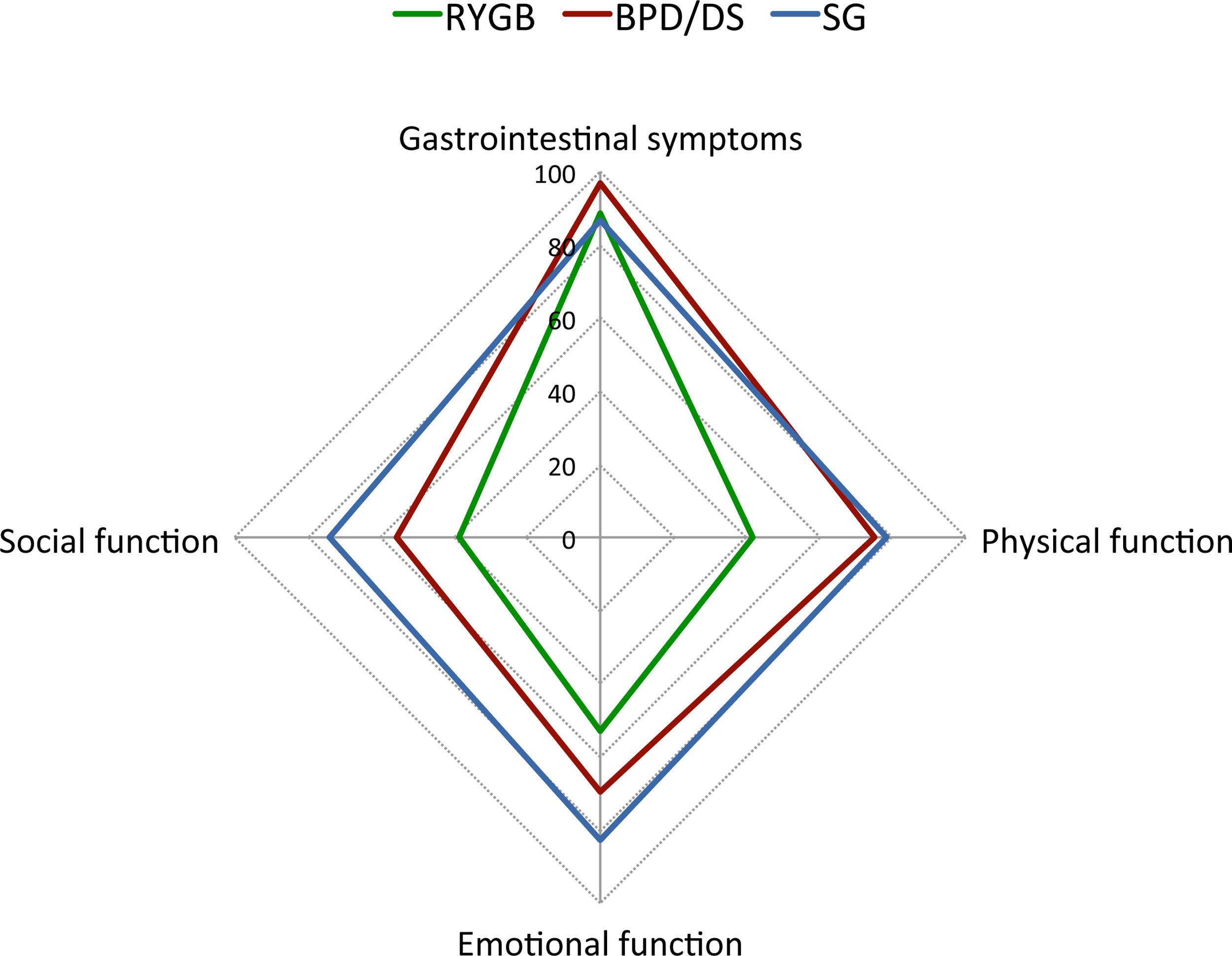

GI symptoms-related QoL was better after RYGB than after SG or BPD/DS (Table 3). No significant association was found between the time from bariatric surgery and the GI symptoms (correlation coefficient of 0.492 for SG, 0.488 for RYGB and 0.771 for BPD/DS). On the other side, physical, emotional, and social function scores, as evaluated by the GIQLI, were significantly lower in patients after SG than in those after RYGB or BPD/DS (Table 3). The proportion of patients with a poor QoL as defined by an abnormally low GIQLI score was significantly greater in patients after SG than in those after RYGB or BPD/DS in all dimensions except in GI symptoms (Fig. 5).

QoL scores (mean±SD) evaluated by the GIQLI after RYGB, BPD/DS and SG.

| Surgical procedure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB | BPD/DS | SG | p value | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 58.3±8.3 | 51.8±8.6 | 53.4±10.6 | <0.01 |

| Physical function | 20.8±5.6 | 19±5 | 14±7.5 | <0.01 |

| Emotional function | 13.4±3.1 | 12.7±3.4 | 10.1±4.2 | <0.01 |

| Social function | 17.3±3.5 | 16.3±3.6 | 13.4±4.6 | <0.01 |

| Medical treatment | 3.8±0.5 | 3.6±0.6 | 3.3±1.1 | 0.09 |

| Total | 112.6±16.7 | 101±16.1 | 93±20.2 | <0.01 |

RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BDP/DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

GIQLI questionnaire. Percentage of patients with altered results compared with the QoL scores reported for the Spanish general population. GIQLI, Gastrointestinal quality of life index; QoL, quality of life; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; BPD/DS, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

QoL scores as evaluated by both SF36 questionnaire and GIQLI showed a significant positive correlation with the %EBMIL (p<0.01) (Table 4). Postprandial fullness correlated negatively with QoL as evaluated by both SF-36 and GIQLI. Abdominal distention and flatulence correlated negatively with QoL as evaluated by GIQLI. Other GI symptoms did not correlate with QoL (Table 4).

Pearson's correlation between QoL, as evaluated by the SF-36 questionnaire and GIQLI, and loss of BMI excess (%EBMIL), psychological disturbances and GI symptoms after bariatric surgery.

| SF-36 | p value | GIQLI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %EBMIL | 0.232 | 0.02 | 0.279 | <0.01 |

| Psichological disturbances | −0.269 | <0.01 | −0.292 | <0.01 |

| Abdominal pain | −0.014 | 0.1 | −0.171 | 0.1 |

| Abdominal distention | −0.09 | 0.39 | −0.264 | 0.01 |

| Postprandial fullness | −0.209 | 0.04 | −0.286 | <0.01 |

| Early satiety | −0.039 | 0.71 | −0.033 | 0.75 |

| Gas bloating | 0.181 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.99 |

| Flatulence | −0.193 | 0.06 | −0.283 | <0.01 |

QoL, quality of life; GIQLI, gastrointestinal quality of life index; BMI, body max index; EBMIL, excess body max index loss; GI, gastrointestinal.

Finally, patients with a worsening of their initial psychological condition had a worse QoL than those who did not have it, both in SF-36 (61.68±22.95 vs. 73.59±19.83, p<0.01) and GIQLI total score (96.9±17.51 vs. 108.02±18.56, p<0.01) (Table 4).

DiscussionBy using the SF-36 questionnaire and GIQLI, the present study shows that GI symptoms, mainly postprandial fullness, abdominal distention, and flatulence, negatively affect QoL in patients after different bariatric surgical procedures. Although a worsening of their initial psychological condition and weight loss are major determinants of QoL after bariatric surgery, GI symptoms play a significant role.

Bariatric surgery has proven to be an effective approach for the treatment of morbid obesity and related morbidities. However, GI symptoms and psychological alterations are frequently present in these patients even long-term after surgery. Although most obese patients experience a short-term reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms after surgery, these symptoms may tend to increase later.20 About 40% of our patients presented psychological disturbances (depression or anxiety), mainly in the SG group, which could be partly related to the lower %EBMIL in these patients undergoing restrictive bariatric surgery.

Patients after bariatric surgery present with GI symptoms, independently of the surgical procedure performed. More than half of the patients referred soft stools, mainly those after BPD/DS. Early satiety is a consistent finding after SG, but it also appears very frequently after malabsorptive procedures. On the contrary, as expected, bloating is more frequently referred by patients after malabsorptive procedures than after SG. Nevertheless, neither early satiety nor bloating affect significantly patients’ QoL. According to our data, postprandial fullness, abdominal distention, and flatulence are the symptoms affecting QoL significantly in patients after bariatric surgery. GI symptoms-related QoL as evaluated by GIQLI was best after RYGB compared with SG or BPD/DS. In the present study, GI symptoms were not influenced by the time after different surgical procedures. In addition, patients after SG showed the worse physical, emotional, and social function scores, and the proportion of patients with a poor QoL as defined by an abnormally low GIQLI was significantly greater in patients after SG than in those after RYGB or BPD/DS in most dimensions. Abdominal pain was present in one out of each five patients of our study, and it has been described as one of the most common complaints after RYGB,13 but it had no impact on patients’ QoL. All these data support RYGB over SG as the surgical procedure for obesity.

QoL as evaluated by the SF-36 questionnaire was significantly worse in patients after SG in most dimensions too. These patients had the lowest %EBMIL and the highest prevalence of depression or anxiety compared with those undergoing malabsorptive procedures, which may explain the negative effect on QoL. In fact, percentage of weight loss has been shown to be significantly associated with QoL.21–23

Our study has several strengths and limitations. On the one hand, it is a prospective and comparative study reflecting daily clinical practice. We are not aware of any other study evaluating and comparing SF-36 and GIQLI scores in patients after SG, RYBG and BPD/DS. We observed a worsening of their baseline physical and psychological condition, depending on the type of surgery, and it is well known that GI anatomical changes are a major determinant of these changes.24–28 On the other hand, the time from bariatric surgery to inclusion into the study was different in patients after different surgical procedures, which could affect both QoL and GI symptoms. In addition, no information was available prior to surgery about non-diagnosed functional disorders, QoL and objectively measured psychological state, which could be unevenly distributed. Finally, the intensity and frequency of abdominal symptoms had not been assessed before surgery, which may influence QoL.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, our study shows that both restrictive and malabsorptive bariatric surgical procedures are associated with GI symptoms physical and psychological disturbances negatively affecting patients’ QoL. Although the presence of different GI symptoms is a consistent finding after any bariatric procedure, postprandial fullness, abdominal distention and flatulence are those significantly affecting QoL in these patients. Compared to SG and BPD/DS, patients after RYGB showed the best GI symptoms-related QoL, which can be used as an additional information for clinical decision making in individual obese patients. Therefore, GI symptoms-related QoL as evaluated by the GIQLI may provide with clinical information that is relevant to the management of patients after bariatric surgery.

Conflict of interestL. Uribarri-Gonzalez, L. Nieto-García, A. Martis-Sueiro, and J.E. Domínguez-Muñoz have no conflicts of interest to declare.