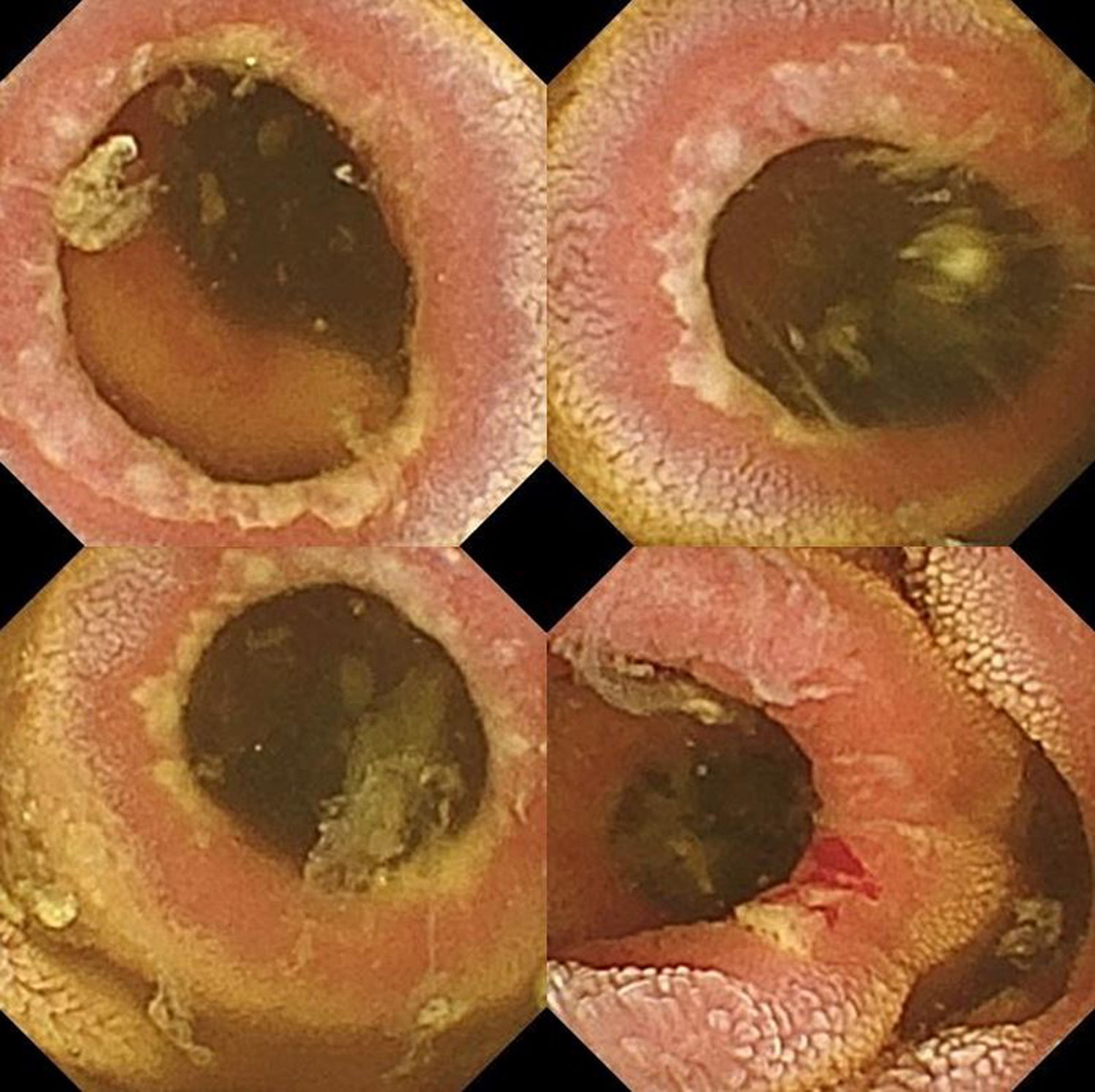

A 57-year-old man with no toxic habits or relevant personal medical history, referred to a gastroenterology clinic for the study of anaemia. The patient reported no gastrointestinal symptoms or external blood loss. Blood test showed haemoglobin (Hb) 7.3g/dl, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 75fl, iron 33g/dl and ferritin normal. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed evidence of an erythematous antrum (stomach biopsies compatible with non-specific chronic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori negative), and colonoscopy showed no lesions. Investigations were completed with intestinal transit which showed no clear stricture and subsequent capsule endoscopy (CE), which revealed the existence of numerous mucous rings with ulcerated edges, some stained with fresh blood, from the duodenum to the jejunum, causing stricturing of the lumen, but allowing the passage of the capsule (Fig. 1). These findings were compatible in the first instance with the diagnosis of small-bowel diaphragm disease (SBDD). Duodenal biopsies ruled out coeliac disease, and assessment for systemic diseases found no data suggestive of other conditions. Repeat questioning of the patient ruled out that he had been taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Treatment was prescribed with oral iron, until the anaemia was completely resolved, and empirical oral mesalazine. Eleven months later, the patient continues to be monitored for anaemia. Enteroscopy shows the persistence of mucous rings from the jejunum onwards, but with improvement in the inflammation round the edges and less bleeding when the tube passes through. Biopsies showed a non-specific inflammatory infiltrate.

SBDD is a rare condition, the prevalence of which is uncertain, characterised by multiple, thin intestinal concentric mucous rings, usually in the jejunum and ileum, although it has also been described in the colon, which, to a greater or lesser degree, cause stricturing of the lumen.1 Histologically, there is lymphocytic and polynuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the mucosa, destruction of the muscular lamina and fibrosis in the submucosa.

The aetiopathogenic mechanism is not fully understood, but it has been related to the use of NSAIDs. The topical effect of these drugs causes fibrosis of the submucosa, and the systemic effect secondary to the inhibition of prostaglandins leads to an increase in the permeability of the intestinal barrier, making it more vulnerable to bacteria and toxins and inflammation, with subsequent scarring, fibrosis and formation of annular septa.1 When no NSAID use is identified, the pathophysiological mechanism is even more uncertain.

Iron-deficiency anaemia, combined with abdominal pain, are the main forms of presentation, and in more severe cases it can be complicated by protein-losing enteropathy, intestinal obstruction, perforation and acute peritonitis.2 Although any condition of the small intestine can be associated with bacterial overgrowth and secondary malabsorption, they do not tend to be the typical feature of SBDD, and no association with other micronutrient deficiencies has been described.3

Radiological diagnostic tests have low sensitivity,3 as the diaphragms can go unnoticed in studies with contrast. Capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy are the most useful methods for identifying SBDD, as they enable the characteristic striking, ringed images to be visualised.3 The only drawback is the possibility of capsule retention, but this can be avoided by performing a patency test with a biodegradable capsule.

The differential diagnosis is broad and includes the extensive group of conditions which cause ulcerative enteritis of infectious aetiology (mainly tuberculosis or CMV), neoplasms (lymphomas), Crohn's disease, coeliac enteritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and systemic diseases (Behçet's disease, for example). In our case, there were no data suggesting a systemic or infectious disease, but the location in particular (throughout the small intestine) and the endoscopic appearance of the concentric rings without evidence of ulcers at other levels pointed to the initial diagnosis of SBDD.

The presence of concentric fibrous rings in the small intestine is also consistent with cryptogenic multifocal ulcerative stenosing enteritis (CMUSE), which is the main differential diagnosis of SBDD. CMUSE is an extremely rare disease, defined by multiple rings and ulcers in the mucosa and submucosa of the small intestine, but not related to the use of NSAIDs, and it seems to respond to corticosteroids.4 The cases described in the literature show ulcerated mucosa between the rings, unlike our patient, where ulceration was located at the edges of the fibrous rings.

In cases of SBDD associated with NSAIDs, it is advisable to discontinue the NSAIDs. Selective COX-2 inhibitors may be an alternative to prevent damage to the gastrointestinal tract, while the use of proton pump inhibitors does not add any protective effect.5 The use of misoprostol and 5-ASA derivatives seems to have promising results due to their anti-inflammatory effect and the alteration of the permeability of the intestinal mucosa, although the evidence is from cases related to NSAIDs.5 In cases of intestinal obstruction or perforation, an emergency laparotomy may be necessary with strictureplasty or resection of the affected segment.

Please cite this article as: Roa Colomo A, Martín-Lagos Maldonado A, Díaz Alcázar MM, Casado Caballero FJ. Anemia ferropénica secundaria a enfermedad de los diafragmas del intestino delgado no asociada a AINE ¿algo más en lo que pensar? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:433–434.