Efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease (CD) showed by randomized controlled trials must be confirmed in clinical practice. We aimed to evaluate efficacy and safety of infliximab in CD patients of the Madrid area, looking for clinical predictors of response.

MethodsMulticenter retrospective survey of all CD patients treated with infliximab in 8 University hospitals of the Madrid area (Spain) with a minimum follow up of 14wks.

Results169 patients included (48%males, mean age 39 ± 12 yrs). 64% of them had perianal disease. 82% were under immunosuppressants. 1355 infliximab infusions administered (mean 8, range 1-30). 90% response rate and 48 % remission rate were obtained with induction therapy. 73% followed maintenance treatment, and 78% of them maintained or improved the response after a mean follow up of 28 months (range 3.5-86). 24 patients lost response during the follow up, after a mean of 41wks (range 6-248). Only the prescription of maintenance therapy was predictive factor for favourable response (p < 0.01). 17 infusion reactions were reported (10% of the patients, 1.2% of the infusions; only one case was severe) and were the cause of treatment withdrawal in 7 patients. Co-treatment with immunosuppressive drugs and maintenance infliximab therapy were protective factors for infusion reactions (p < 0.05). Other adverse events occurred in 26% of the patients, and were cause of treatment withdrawal in 7 patients.

ConclusionsInfliximab is effective and safe for CD management but concomitant immunosuppressive drugs and maintenance treatment should be prescribed to obtain the best outcome. That confirms in a real life clinical setting the favourable results obtained in randomized clinical trials.

La eficacia de infliximab en la enfermedad de Crohn (EC), demostrada por los diferentes ensayos clínicos, ha de ser confirmada en la práctica clínica. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad del infliximab en pacientes con EC del área de Madrid, buscando predictores de respuesta.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo y multicéntrico que incluye los pacientes con EC tratados con infliximab en 8 hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid, con un seguimiento mínimo de 14 semanas.

ResultadosSe incluyó a un total de 169 pacientes (un 48% varones, con una edad de 39 ± 12 años), un 64% con enfermedad perianal y un 82% bajo tratamiento inmunosupresor. Se administraron un total de 1.355 perfusiones de infliximab (media, 8; rango, 1-30): un 90% de los pacientes respondió, un 48% alcanzó la remission clínica, un 73% siguió tratamiento de mantenimiento, y un 78% mantuvo o mejoró su respuesta tras un seguimiento medio de 28 meses (rango, 3,5-86). Se perdió la respuesta durante el seguimiento de 24 pacientes, tras una media de 41 semanas (rango, 6-248). Sólo la prescripción de tratamiento de mantenimiento fue un predictor favorable de respuesta (p < 0,01); se contabilizaron 17 reacciones infusionales (en el 10% de los pacientes, el 1,2% de las perfusiones; sólo se constató un caso grave) y fueron causa de la suspensión del tratamiento en 7 pacientes. El cotratamiento con los inmunosupresores y el tratamiento de mantenimiento con infliximab fueron los factores protectores para sufrir reacciones infusionales (p < 0,05). Otros efectos adversos se produjeron en el 26% de los pacientes, y fueron causa de suspensión del tratamiento en 7 pacientes.

ConclusionesInfliximab es eficaz y seguro en el tratamiento de la EC, pero deberían prescribirse el tratamiento de mantenimiento y el concomitante con inmunosupresores para obtener los mejores resultados. Esto confirma en un escenario de práctica clínica real los resultados obtenidos en ensayos clínicos.

The therapeutic approach to Crohn’s disease (CD), a chronic and disabling inflammatory bowel disease, has evolved intensely in the last decade. Since steroids are not useful in maintaining long-term remission, as documented in classic population-based studies1–4, immunosuppression with thiopurinic agents (i.e. azathioprine or mercaptopurine) or methotrexate have been widely used, even though they all have limited value for induction of response and can only benefit less than half of the patients that suffer from steroid dependency or resistance5–9.

Despite the above, this conventional therapy is far from achieving a satisfactory control of the disease in a majority of the patients: Less than 50% of the CD patients seem to be asymptomatic 2 years after the initial diagnosis3. This frequently unfavourable course of the disease leads the patients to complications that may require surgery, even though resection of the affected portion of intestine does not affect the disease outcome10. Moreover, the widespread use of immunosuppressive therapies does not seem to modify the risk of surgery11. In this respect, modern biologic therapies may be the key to a disease modifying therapy.

Cytokines play a central role in modulating inflammation, and they may, therefore, be a logical target for inflammatory bowel disease therapy using specific cytokine inhibitors12–15. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF α) is a key proinflammatory cytokine in Crohn’s disease and in other chronic inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis12–14. Infliximab (Remicade®, Centocor; Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA) is an intravenously administered chimeric monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 antibody to TNF□. Several randomized controlled trials have shown infliximab to be an effective therapy for CD patients with moderate-severe and fistulizing disease, not responding to conventional drug treatment12–14,16–19. Thus, infliximab was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998 and by the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) in 1999 for the treatment of active, as well as fistulizing CD20, and the efficacy to induce response and remission that is reported in placebo controlled trials has been confirmed in some open observational studies21–28.

Even though it seems clear that maintenance therapy with infliximab every 8 weeks is the optimal regimen for patients treated for refractory luminal or fistulizing CD19, there are only few and small studies that assess efficacy and safety of the long-term maintenance treatment with infliximab in the real clinical setting29–33 and some controversial issues exist about the convenience and the duration of long-term maintenance therapy.

Although randomized clinical trials are mandatory, observational studies are needed to obtain data from the real life clinical setting. Therefore, we aimed to communicate the corporate experience with the clinical use of infliximab in CD patients in a group of major public hospitals in the area of Madrid, Spain; it is a large multicenter retrospective study that includes long-term followed up patients in maintenance treatment.

METHODSWe retrospectively reviewed the records of all the CD patients that have received infliximab at some time in 8 hospitals of the Madrid area (Spain) with a minimum follow up of 14 weeks. Demographical data were collected in all cases, as well as updated follow-up data concerning the evolution of the disease, including time of evolution of the disease, smoking habit, concomitant treatments, dose and number of infusions, the type of treatment (single, on demand or scheduled) and adverse events.

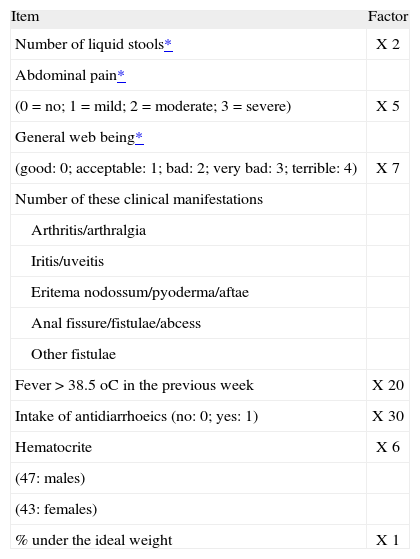

Regarding the activity of the disease and the response to infliximab therapy, Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI, table I) was calculated before the beginning of the infliximab therapy and by the 6th week after starting the treatment, as well as at the longest follow up on every case (the so called long-term response). In those cases where some CDAI score was missing, it was retrospectively calculated.

Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI)

| Item | Factor |

| Number of liquid stools* | X 2 |

| Abdominal pain* | |

| (0 = no; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe) | X 5 |

| General web being* | |

| (good: 0; acceptable: 1; bad: 2; very bad: 3; terrible: 4) | X 7 |

| Number of these clinical manifestations | |

| Arthritis/arthralgia | |

| Iritis/uveitis | |

| Eritema nodossum/pyoderma/aftae | |

| Anal fissure/fistulae/abcess | |

| Other fistulae | |

| Fever > 38.5 oC in the previous week | X 20 |

| Intake of antidiarrhoeics (no: 0; yes: 1) | X 30 |

| Hematocrite | X 6 |

| (47: males) | |

| (43: females) | |

| % under the ideal weight | X 1 |

Response was defined as a significant reduction in the CDAI (at least 70 points), which should be below 150 points to be considered clinical remission. In those patients that were under steroid therapy, a significant decrease in the dose was also required for the definition of response, and a full discontinuation for considering clinical remission. For fistulizing disease, direct evaluation was performed in all cases and fistula improvement (response) was defined as closure of 50% of particular fistulas that were actively draining at baseline, spontaneously or with gentle compression, and fistula remission was defined as closure of all particular fistulas what means absence of drainage, spontaneous or with gentle compression.

Statistical analysisFor quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated. For categorical variables, percentages and corresponding 95% intervals (95%CI) were provided. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically signifi cant. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test, and quantitative variables with the Student t test.

RESULTSThere were 169 CD patients who received infliximab therapy for refractory luminal or fistulizing disease in 8 major public hospitals in the Madrid area (Spain).

DemographicsPatients were almost equally distributed in gender: 48% of them were males and 52% were females. Regarding age, patients were between 18 and 92 years of age (mean age 39 ± 12 years). Active smoking habit was reported by 61% of the patients when infliximab therapy was started.

Characteristics of the disease before infliximab therapyThe distribution of the patients according to the Montreal Classification was as follows: Regarding the age of diagnosis, 11% were diagnosed at 16 years or under (A1), 77% between 17 and 40 years (A2), and 12% were diagnosed over the age of 40 (A3); regarding the localization of the disease, 14% affected the terminal ileum (L1), 26% the colon (L2) and 60% had ileocolic disease (L3); 40% of the patients included had inflammatory behaviour (B1), 11% had stricturing behaviour (B2), and 48% had fistulizing disease (B3). Perianal disease was documented in 64% of the patients, including 6 cases of rectovaginal fistula.

Before starting infliximab therapy, 82% of the patients were receiving immunosuppressants: 78% were under thiopurinic agents, 4% were under methotrexate. Only 18% of the patients were receiving no immunosuppressive drugs before infliximab.

Previous surgery related to the CD was reported in 67% of the patients included: 22.5% of the patients had undergone surgery related to luminal or stricturing complications, 30% had needed surgery due to perianal disease, and 14% had needed surgery for both reasons.

Infliximab therapyMost of the patients (156; 92%) started this treatment with the usual induction therapy (infusion administered at the 0, 2nd and 6th week), with a response rate of 90% (95%CI, 85-95) and 48% (95%CI, 39-56) remission rate by the end of this period. Most of the patients (114; 73%) who started induction therapy followed maintenance treatment, and 90 (78%; 95%CI, 67-84) of them maintained or improved the response obtained by the 6th week. In the remaining 24 patients (22%) who lost response, dose was increased in 10 of them, infusion interval was shortened in 5, and treatment was withdrawn in 9 patients. Among the 15 patients whose infliximab administration was modified, 10 achieved a good outcome that lasted for a mean of 19 weeks (range, 4-40 weeks). When response was lost, it occurred after a mean period of 41 weeks (range 6-248 weeks) after the initial dose of infliximab.

After a mean follow up of 28 months (range 3.5-86 months), the total number of infliximab infusions was 1355 (mean 8 infusions per patient; range 1-30) and 95 patients (56% of the total number of patients initially included) had achieved complete response since they were considered to be in clinical remission, 52 patients (31%) had reached partial response and 22 patients (13%) were considered treatment failures.

We found no relationship of statistical significance between the clinical outcome and sex, age, smoking habit, Montreal classification (including the presence of fistulizing disease), number of years of evolution of the disease, surgical records or the immunosuppressive concomitant therapy. The only predictive factor that we found for the long-term favourable response to infliximab was the prescription of scheduled maintenance treatment (p < 0.01).

Safety issuesDespite the fact that 78% of the patients received premedication with steroids or antihistaminics, 17 cases of infusion reactions were reported, which means 10% (95%CI, 5.5-15) of the patients, 1.2% (95%CI, 0.8-2) of the infusions. Eight of them were immediate, and 9 were delayed reactions; regarding its severity, 50% were mild, 43% moderate, and only 1 case of severe infusion reaction was reported.

The infusion reactions were managed as follows: No therapeutic intervention was required in most cases (53%), additional steroids were needed in 6%, the infusion had to be slowed in 7%, and had to be stopped in 33% of the cases. Infusion reactions were the cause of treatment withdrawal in only 7 patients (30% of the patients that had to stop the treatment). We found no relationship of statistical significance between the presence of infusion reactions and sex, age, smoking habit, Montreal classification, number of years of evolution of the disease or surgical records. Co-treatment with immunosuppressive drugs and administration of maintenance infliximab therapy were the only protective factors for infusion reactions (p < 0.05).

Other adverse events were documented in 26% of the patients, including headache (5 cases), gastrointestinal symptoms (5 cases), asthenia (4 cases), arthralgia (4 cases), myalgia (7 cases), fever (2 cases) and pruritus (2 cases). Adverse events not clearly labelled as infusion reactions were responsible for treatment withdrawal in 7 cases. No case of opportunistic infection or active tuberculosis was reported during the follow-up. Taking all these safety issues into account, 14 out of the 169 patients included (8%; 95% CI, 4.1-12) had to abandon infliximab therapy due to adverse events.

DISCUSSIONEven though infliximab was approved by the FDA for refractory CD almost 10 years ago, it is remarkable that post-marketing studies are still scarce. We believe that independent observational studies are necessary to confirm in the clinical setting the outcome from the large randomized clinical trials, in terms of both efficacy and safety. Moreover, long-term follow-up series of infliximab treated patients in real clinical practice are clearly lacking. We present the current experience with infliximab in CD in a group of several major hospitals of the Madrid area, which provides long-term follow-up data.

Induction therapy with infliximab obtained a very good outcome, which was almost twice than that reported in randomized controlled trials. The reason that may explain this outstanding difference between clinical trails and clinical practice should be found in the selected patient population, since the daily practice indication to receive infliximab seems to be stricter than the ACCENT inclusion criteria17,34. Regulations concerning clinical trials required to register a new drug do not always reproduce the clinical reality.

As previously stated in the ACCENT trials, systematic scheduled treatment every 8 weeks is the optimal strategy for infliximab to be administered17,19,34. This was confirmed in our experience since those patients who did not undergo scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab were those who achieved a poorer outcome. On the other hand, most of our patients were under immunosuppressive drugs at the time of starting infliximab therapy. This has been previously pointed out as a predictive factor for response in some studies35–37 but it has not been confirmed by our experience in terms of clinical efficacy although it seems to be important in terms of safety, as it has been highlighted by our results.

Therefore, maintenance infliximab therapy and combined therapy with immunosuppressive drugs are the only predictive factors of good outcome that we found in our experience, which is very consistent with previously reported data obtained from randomized clinical trials12,17,19. Some other clinical predictive factors have been proposed in previous studies (stricturing behaviour38, smoking habit36,37 or the presence of rectovaginal fistula39), but none of them was useful in our experience. The factors that we found to be predictive of outcome are believed to be related to the development of antibodies to infliximab (ATI): Episodic instead of scheduled maintenance treatment is more immunogenic and related with higher levels of ATI; these high ATI levels are related to a reduction in the serum concentration of infliximab, and consequently to a reduction in the strength and the duration of the response40–43. As a matter of fact, recently published pharmacokinetic studies show that the clinical outcome is strongly related with the serum concentration of infliximab and the presence of ATI might be a surrogate marker for the effects of absent serum infliximab43,44. On the other hand, concomitant immunosuppressive agents are thought to prevent the development of these ATI40–43, even though differences in efficacy between patients with or without ATI, with or without concurrent immunomodulators, have not been clearly found40,43. Therefore, our experience confirms that those patients that receive concomitant immunosuppressive therapy and are enrolled in scheduled maintenance therapy are more likely to obtain good response in the long-term.

Long-term follow up data show that patients may loose the obtained response to infliximab. Almost one of every four patients treated in our study lost their response in a relatively short period of time, which is consistent with the data obtained from randomized controlled trials17,34. The management of these cases is not clearly stated in the literature, but it seems that increasing the infliximab dose or shortening the interval between doses may be rational alternatives19. By doing so, we obtained good outcome in most of the patients that had lost their response to infliximab but, once again, for a limited period of time. There is no doubt that the long follow up carried out in this study allowed this complication arise in a remarkable proportion of the patients. The management of this further situation is beyond scientific evidence, and it is not described in randomized trials. Once again, the presence of ATI is believed to be the cause of this phenomenon40 and therefore availability of new anti-TNF molecules may be the key for these patients to keep the infliximab induced response45.

Our experience confirms in a clinical setting that infliximab is safe, as infusion reactions were rare and most of them were mild or needed no therapeutic intervention. The presence of ATI is related to a 12% increase of infusion reactions40,43; scheduled maintenance treatment and concomitant immunosuppressive agents were the only protective factors for infusion reactions in our experience, and this might be related to the reduction in the incidence of ATI that these two strategies provide in the long-term43. Moreover, only a small minority of our patients had to quit from infliximab due to intolerance. On the other hand, serious infectious complications have not been described in our experience, and this fact must be related to the generalized compliance of the recommendations made by the Spanish Working Group on CD and UC (GETECCU) for the use of Infliximab in CD that were published in 2002 and updated in 200546,47.

In conclusion, this real life clinical setting experience confirms results from previous randomized controlled clinical trials: Infliximab is safe and effective for treating CD patients, but its immunogenicity represents a clinical problem in the long-term, so scheduled maintenance therapy and concomitant immunosuppressive drugs are needed to obtain the best outcome. Moreover, loss of response is a fact in the long-term clinical practice. Updated strategies to preserve the infliximab induced response must be defined.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

CIBERehd is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.