According to data from the World Tourism Organization, in 2018 up to 1,400 million people travelled internationally, to which must be added more than 70 million forced relocations due to conflicts.

Until the advent of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, air travel offered an unbeatable expansion route for infectious diseases, especially those with a short incubation period. This has led to the rise of epidemic outbreaks in countries with factors that facilitate gaining a foothold, whether for ecological (existence of vectors such as the Asian tiger mosquito) or social reasons.

The Angiostrongylus genus of nematodes has two subspecies that are pathogenic in humans: A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis. These helminths have a complex life cycle with five phases of development in marine invertebrates as intermediate hosts and rodents as definitive hosts. People are accidental hosts, and can become infected by eating raw or undercooked shellfish.1,2 After a two-week incubation period, the infection manifests with a clinical picture dominated by abdominal symptoms caused by the direct invasion of the bowel wall (A. costaricensis) or neurological symptoms secondary to eosinophilic meningitis (A. cantonensis). A. costaricensis commonly causes bowel perforation due to its inherent cytopathic effect and tissue anoxia secondary to intense eosinophilic vasculitis.3 Both infections have been well documented in tropical countries, but are practically unknown in Europe.

The patient described is one a group of nine tourists travelling from Cuba. Between days 14 and 17 from their return to Europe, four of them presented symptoms compatible with angiostrongyliasis. The source of infection was identified (eating undercooked prawns). The initial clinical presentation in three patients (intense retro-ocular and occipital headache, nausea and meningism with dysaesthesia plus severe eosinophilia in blood and cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]) matched the symptoms of parasitic eosinophilic meningitis. The fourth patient also presented episodes of intense abdominal pain.

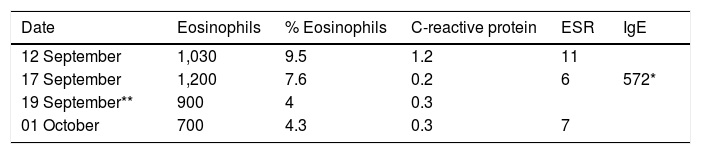

She was a 20-year-old woman with a history of extrinsic bronchial asthma. At 17 days from her return, she was treated in the Infectious Diseases Department after reporting headache, nausea and an intense sensation of dysaesthesia in both knees, which was partially disabling, although without joint limitation or effusion. The complete blood count revealed hypereosinophilia (1,030 eosinophils; 9.5%). Baseline biochemistry was without abnormalities in liver and kidney function or elevated acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein [CRP]: 1.2 and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]: 11mm/h). She was prescribed methylprednisolone 1mg/kg and analgesia as instructed.4 Nevertheless, her evolution was markedly different from the other three patients, in whom the meningeal symptoms intensified requiring hospital admission and an evacuatory lumbar puncture. In the fourth patient, the appearance of cutaneous allergic reactions and episodes of migrating (left occipital, left arm and pharynx) paraesthesic pain predominated. From the seventh day of symptoms, the pain increased and focused in the left hemiabdomen, requiring assessment in the Surgical Emergency Department.

On examination, the abdomen was soft, depressible, undistended but painful to palpation on the left flank and iliac fossa; there were no signs of peritonitis. Hypereosinophilia persisted in analytical tests (Table 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed normal bowel loops, with no signs of wall involvement or other visceral abnormalities. In a joint Surgery and Tropical Medicine assessment, the clinical picture was viewed as one of paraesthesic abdominal pain, a surgical approach was ruled out and alprazolam and antihistamines (bilastine) were added to her treatment, obtaining an excellent clinical response with the symptoms disappearing over the next four or five days. Subsequently, serology (In-Home EITB, The Swiss Tropical & Public Health Institute, Geneva, Switzerland) confirmed positivity for Angiostrongylus cantonensis.

This helminth has undergone a silent but rapid expansion from southeast Asia to the Caribbean, and is considered a global emerging parasitic disease. The onset of abdominal pain in a patient with suspected angiostrongylosis calls for close monitoring, as we do not have immediate tests that can differentiate between A. cantonensis and the much more intestinally-damaging A. costaricensis.

Clinical pictures dominated by paraesthesic pain due to A. cantonensis are evidently rarities, but similar cases have been described in highly endemic areas: Hawaii (four out of 18 cases: 22%), China (five out of 25; 20%) and one in Australia.5 “Paraesthesic” patients report intense painful sensations located “under the skin”, that often radiating metamerally, migrating, disabling due to its intensity, but appearing normal on physical examination. They typically live in agony and respond to a combination of benzodiazepines and antihistamines, although the reasoning behind their therapeutic effect is disputed; note that a population of eosinophils sensitised to helminth antigens may produce cytokines with neurotropic effects.

Ultimately, we present the first serologically confirmed case of A. cantonensis in Europe with a clinical picture dominated by episodes of abdominal pain of paraesthesic origin requiring a surgical assessment. The history of travel to endemic areas and hypereosinophilia may be suggestive of this diagnosis.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Valerio Sallent L, Moreno Santabarbara P, Roure Díez S. Dolor abdominal secundario a Angiostrongylus cantonensis neuroinvasivo; primer caso europeo. Algunas reflexiones sobre las parasitosis emergentes. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:566–567.